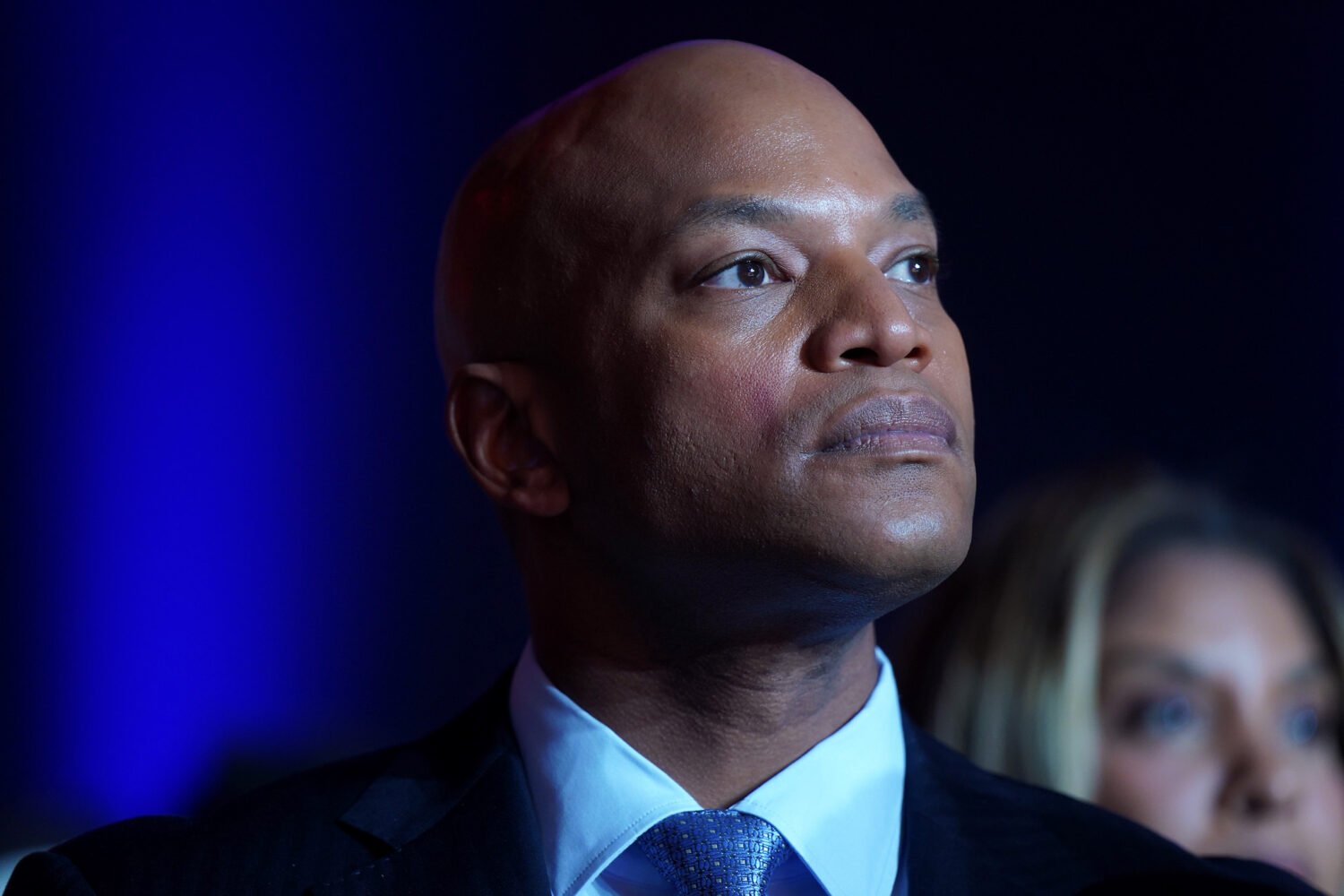

Governor Larry Hogan first noticed the lump while shaving. One day it wasn’t there, the next you couldn’t miss it: a golf-ball-size mass bulging from his neck, just above his Adam’s apple.

“Honey,” the governor called to the first lady. “Take a look at this.”

It was Saturday, June 6, 2015, the final day of a trade mission to Asia, and the Hogans were in their hotel room in Tokyo preparing for the 14-hour flight home.

“Does it hurt?” the first lady asked.

It didn’t. But its size and sudden appearance were troubling, so the governor had it checked out Monday morning on his return to Annapolis. Doctors initially thought it might be only a cyst, but—just to be sure—a physician ordered an MRI. Hogan was alone in the doctor’s office, waiting for the results, when a radiologist, a general surgeon, and an ear-nose-and-throat specialist filed into the room together. “We have some bad news,” one of them said.

The governor had as many as 60 tumors—some as big as grapefruits—stretching from his neck to his groin. The doctors believed that Hogan had an advanced and aggressive form of lymphoma, a blood cancer. He’d need to see an oncologist immediately and—if their suspicions were confirmed—begin chemotherapy right away.

“I mean, out of the blue,” Hogan says. “I didn’t really feel sick; I just had this funny thing sticking out of my neck.”

***

Hogan, of course, wasn’t supposed to be governor in the first place. During the 2014 campaign, this little-known “Anne Arundel County businessman,” as the press took to identifying him, was the GOP’s Hail Mary nominee—outspent by a three-to-one margin in a state with twice as many Democrats as Republicans. His upset victory made Hogan only the second GOP governor to lead Maryland in almost 50 years.

Now, only five months after his swearing-in, three physicians were telling Hogan that his life was about to change once again. “I didn’t get visibly upset, I wasn’t like scared—I was just processing,” he says. “I’m thinking about all the things I have to do.”

Such as tell his wife and three daughters, his chief of staff, and the people of Maryland.

Over the next ten days, additional tests confirmed Hogan’s diagnosis, and the governor scheduled a press conference for the afternoon of June 22. That morning, he returned to the hospital for a bone-marrow biopsy, which required anesthesia and heavy-duty painkillers. In preparation, a nurse issued instructions for his recuperation: Don’t drive for the rest of the day. Don’t operate heavy machinery. Don’t make any major decisions.

“Well, the troopers don’t let me drive the car anyway; I’m not going to do any machinery,” Hogan says he responded. “But I am going to have a press conference at 2 o’clock today.”

Aghast, the nurse chased down the doctor, who tried to talk the governor out of it.

“You’re not going to be making much sense—you’re going to be a little loopy,” Hogan remembers him saying. “You’re going to be hurting, and I would really suggest that you don’t do that.”

Hogan declined the advice. He had been canceling appearances, which triggered whispers about his health—including, according to an aide, a rumor that he’d caught Middle East respiratory syndrome on his trade mission. Now that he’d be starting chemo, he wanted to be straight with the public: “I can’t really wait.”

So after the biopsy—and with Percocet and Vicodin in his system—the governor stood before a podium in the statehouse to deliver news of his diagnosis; announce his imminent chemo regimen; and promise state residents that he’d work right on through it, like any other cancer sufferer.

At the end of the sometimes emotional press conference, when a reporter asked if anything might prompt him to relinquish authority to the lieutenant governor, Hogan broke the tension. “I mean, if I died,” he said as the crowd fell into laughter, “I would say he probably is gonna take over.”

With that, Hogan won the room—he managed to turn a personal trauma and a delicate matter of governance into a clip for his highlight reel. “I think it was because I was heavily sedated,” he later told me. “I was like [on] truth serum.”

Hogan’s first term has been defined by folksy moments just like this one, helping explain how a little-known Republican became the beloved governor of a profoundly blue state—and created a catastrophe for Democrats. Hogan is now America’s second-most popular governor, according to the media-and-survey-research firm Morning Consult. In Washington Post polls, his approval ratings have soared from 47 percent in February 2015 to 71 percent in October 2016. How did he do it? Workaday populism, moderate instincts, impeccable stagecraft—and a lot more training than most people realize.

“It’s sort of like an overnight star, right? Somebody who hits it big, and then you say, ‘Oh, my God—where’d they come from?’” says Russ Schriefer, a media consultant to Hogan’s campaign. “Then you talk to them and they say, ‘Well, I started taking piano when I was nine.’”

***

Hogan had been Governor for only 88 days when Freddie Gray died from injuries sustained while in the custody of Baltimore police. As peaceful protesting devolved into violent riots, the rookie governor found himself in the middle of the kind of crisis that permanently defines a politician. And he’d never held elected office before.

Around 3:30 that afternoon, Hogan was in the back seat of an SUV heading to an event at the home of the South Korean ambassador in Washington. The vehicle was halfway down Route 50 when his assistant handed him an iPad, “and it shows a police car on fire,” Hogan says. The state trooper driving his SUV made a U-turn, switched on the siren lights, and raced back to the statehouse.

From the back of the SUV, Hogan called Baltimore mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, a Democrat. He had put the National Guard on alert and was ready to give the mayor whatever assistance she needed. But Rawlings-Blake, Hogan says, told him she had the situation under control.

“I said, ‘Well, with all due respect, it doesn’t look like it’s under control. It looks like police cars are burning and the people are overwhelming your city police force.’”

The mayor again declined his help, Hogan says, but the two agreed to stay in touch throughout the day. Over the next three hours as the rioting escalated, Hogan says he tried repeatedly—and unsuccessfully—to track down Rawlings-Blake. Finally, around 6:30 pm, he says he got her on the phone: “She magically appeared.”

Hogan explained that he had two executive orders in front of him. The first, he says, read that “at the request of the mayor of Baltimore” Hogan was declaring a state of emergency and deploying the National Guard. The second also declared a state of emergency but did so on the governor’s own authority. “I said, ‘I think it’s better for you and better for me, and I think PR-wise it’s better for you to request for me to come in. But either way, we’re coming in.’”

The mayor said she needed more time to make a decision, according to Hogan. “I said, ‘There’s no more time. It’s been three hours—the city’s on fire.’ ” They agreed on an additional 15 minutes. “She calls back in 14 minutes and she says, ‘Since you have a gun to my head and since you are going to do it anyway, I guess I’ll ask you to come in.’”

“I go, ‘Okay, thank you very much.’ Click.” (Rawlings-Blake declined to comment.)

Hogan moved his management team to Baltimore, and for the rest of the week, tailed by TV cameras, he walked the streets to talk to residents and show his support. He brought one of his African-American advisors, Keiffer Mitchell, a Democrat who had joined his administration after representing Freddie Gray’s neighborhood in the city council and state legislature.

On Wednesday of that week, Mitchell and the governor arrived at the intersection of North and Pennsylvania avenues in west Baltimore, where some of the most intense rioting had occurred. According to Mitchell, Hogan greeted the Korean shop owners in their native language; he’d learned a few words from his Korean-born wife. Next, they encountered a group of three African-American men in their late teens or early twenties. “Tattoos on their neck and everything,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell approached the men to see if they’d like to meet the governor. “They were angry,” Mitchell says, “They were like, ‘Who’s he? What’s he doing here? He’s not going to do anything.’ ”

The young men had serious grievances: They wanted the police to stop harassing them; they needed jobs and better community resources. “I hear you,” the governor responded. But for now, he needed their help to keep the city safe. “You all do that,” Hogan promised, “I will make sure that I will work on those issues with you.”

According to Mitchell, the men’s demeanors changed: “They said, ‘We feel you, Guv. We feel you.’ ” Then, one by one, each took out his cell phone and snapped a selfie with Hogan. After saying goodbye, the governor popped into a snow-cone stand, ordered a blue snowball, and continued with that day’s walking tour, ice in hand.

***

Hogan is just as loose one on one as he is with a crowd, as I learned when I visited him at his Annapolis office in November. He couldn’t go more than a couple of minutes without cracking a joke.

On why he didn’t play sports at DeMatha high school in Hyattsville: “I loved basketball, but I was short and white.”

On his near addiction to Facebook: “It’s like Trump with the Twitter. [My staff is] like, ‘Oh, no—he’s on Facebook again.’ ”

On his decision to disavow the new President: “Shows how much we know.”

At age 60, Hogan’s appearance hasn’t fully recovered from cancer treatment. His gray-and-white hair remains thin and patchy, and he’s been able to shed only half of the 40 pounds he added to his already chunky frame during chemo. (The weight gain was the result of the drugs, but also of the hamburgers and milkshakes his daughter smuggled into his hospital room.)

In Hogan’s office, there’s an autographed guitar from Tim McGraw, whose song “Live Like You Were Dying” became meaningful to Hogan after his diagnosis. Pictures of the governor with various public figures—the Obamas, Chris Christie, the pope—fill out the room. But the item Hogan hands me is a black-and-white photograph of a man in a suit alongside a chubby kid. “This is 12-year-old me with my HOGAN FOR CONGRESS hat, he says, “and this is my dad right before he got elected.”

As a boy in Landover, Hogan was the neighborhood entrepreneur. He delivered the Washington Daily News and the Evening Star after school and put out his own ten-cents-a-copy newsletter about local happenings—stolen bikes, sandlot baseball games: “People just basically thought it was cute that this young punk was trying to publish a newspaper.”

But he also played junior attaché to his father, Larry Hogan Sr. A former FBI agent, Hogan Sr. launched his political career in 1966 when he ran to represent parts of Prince George’s and Charles counties in Congress. Democrats in the district outnumbered Republicans four to one, and although Hogan Sr. lost that first race, he won on his second try, in 1968.

Months later, Hogan stood next to his father on the floor of the US House of Representatives as lawmakers were sworn in. “I said, ‘Now, look,’ ” Hogan Sr. recalls. “ ‘When they give me the oath of office, you raise your hand and you take the oath of office, too. Because then we’d have two congressmen from Prince George’s County.”

Stuffing envelopes for his dad, tagging along to meet voters, and then, as a teenager, hanging out in his father’s Capitol Hill office on weekends—it was all part of Hogan’s political education. He became a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1976, before he finished college.

The elder Hogan stepped down from Congress in 1975, then became county executive of Prince George’s. Hogan joined the staff; he was “energetic—a mile a minute,” says former Republican governor Bob Ehrlich, who met him around this time. “Very, very devoted to his dad.”

In 1981, Hogan jumped into politics himself by trying to win back his father’s old seat in Congress. At the time, Hogan was a cookie-cutter Republican: resistant to taxes, skeptical of regulations, and for abortion restrictions. And at 24, he was so young that if he’d won, he would have had to wait until his next birthday to be sworn in. “We didn’t have to worry about it,” Hogan says, “because I got smoked in the primary.”

He tried again in 1992. This time, Hogan made it to the general and won four out of five counties but couldn’t oust the fourth-ranking Democrat in the House, Steny Hoyer. Fortunately, he had a business to fall back on. After his first attempt at Congress, he founded a real-estate firm that brokered and developed vacant land around Anne Arundel County—an ideal line of work for a well-connected backslapper. But in 1994, during a cascade of bank failures, Hogan says his lenders called in their loans and he had to declare bankruptcy. As a result, according to court filings, he sold his $750,000 house in Upper Marlboro and other assets. “It was a real low point in my life,” he says.

Over the next several years, Hogan rebuilt his business and started a family. He met artist Yumi Kim at an art show in 2001. The couple married three years later, and Hogan became a father to Kim’s three daughters from a prior marriage.

Hogan returned to politics in 2003, when his old buddy Ehrlich became governor and named him appointments secretary, in charge of filling jobs at state agencies, boards, and commissions. It turned out to be more complicated than the title suggested. In 2005, after Democratic lawmakers accused the governor’s administration of firing Democratic state workers on account of party affiliation, the legislature held hearings. When Hogan’s testimony conflicted with another witness’s, some lawmakers called for him to be charged with perjury. (At the time, Hogan called the entire exercise a political “witch hunt.”)

Lawmakers eventually determined that some firings had indeed violated constitutional rights, but no charges were filed. Hogan kept his cabinet post, leaving only after Ehrlich was defeated by Baltimore mayor Martin O’Malley in 2006. Maryland’s once-in-a-generation experiment in Republican power, it seemed, was over.

***

In 2009, Hogan approached GOP consultant Steve Crim about creating a political organization he wanted to call Change Maryland. “I thought the name was a little bit simple,” Crim says. “But I’ve learned from [Hogan] that simple messaging is important.”

At the time, Governor O’Malley was plugging away at an agenda that would eventually turn Maryland into one of the most progressive states in the US—tightening gun laws, banning the death penalty, and legalizing same-sex marriage, all while plowing state cash into infrastructure and schools. To finance his efforts and to cushion the blow of the recession, O’Malley used new taxes. In 2007 and 2008, for example, he increased taxes on corporations and the wealthy, real-estate transfers and car owners. Says Crim: “We knew that the state was on the verge of a tax revolt.”

Hogan had considered challenging O’Malley in 2010 but backed off when Ehrlich entered the race. Still, he’d seen how his father had won in a Democratic stronghold by urging fiscal restraint. He thought forming a grassroots group that focused on pocketbook issues—and ducked social-policy hot potatoes—could unite Marylanders hurting from the recession. With social media, his group could reach people inexpensively. “I’m not a big high-tech guy,” Hogan says, “but I said, ‘I want to know how to do this Facebook stuff.’ ”

He personally bankrolled Change Maryland, which he ran out of his real-estate firm with Crim and two others. A twitchy news obsessive who e-mailed or texted Crim up to 40 times a day, Hogan proved to be a preternaturally gifted Facebook provocateur; he banged out posts ripping O’Malley’s fiscal policy and engaged directly with his audience. (“He reads the comments,” Crim says.) Meanwhile, the organization kept a tally of O’Malley’s tax-and-fee increases—eventually totaling more than 40—and produced research suggesting that higher taxes were chasing wealthy Marylanders out of the state.

I’m this little punk, sitting in my boxers, typing on Facebook, and O’Malley decides to go toe to toe with me.

The effort drew blood. In response to that report, an O’Malley spokesman called out Hogan as a “failed congressional candidate and failed would-be candidate for governor.”

“I’m this little punk, out here [in the middle of] nowhere, sitting in my boxers, typing on Facebook,” Hogan says, “and O’Malley decides that he’s going to go toe to toe with me.”

A swipe from the governor—it was just what Hogan needed. It raised his profile, and he soon became the media’s go-to source for anti-O’Malley sound bites. “We became the voice of the opposition,” Hogan says. “We were like the government in exile.”

He launched his campaign for governor in January 2014 at Mike’s Crab House near Annapolis. “I’m not a guy who’s been in politics my whole life,” Hogan told the Baltimore Sun. It wasn’t exactly true, of course, but his political identity was now so closely tied to Change Maryland that he could easily pass as just another Main Street small businessman.

The campaign was every bit as bootstrapped as Change Maryland had been. Hogan had to dip into public-financing coffers, something no general-election candidate for governor had done in two decades. “There were weeks where we were trying to figure out if we were going to have enough money to do payroll,” says Schriefer, Hogan’s campaign media consultant. At one point, internal polls showed him trailing his opponent, Lieutenant Governor Anthony Brown, by 12 points. But as Hogan successfully linked Brown to the increasingly unpopular O’Malley, the lead narrowed.

On election night, Hogan and his family gathered around the TV in a suite at the Westin in Annapolis. The excitement built as results came in, and by 9:30 it was clear to Hogan he’d won. But Brown hadn’t called to concede. Hours passed. “I’m going down there,” he told the room. But others insisted he couldn’t deliver his victory speech until Brown conceded or a major news outlet declared Hogan the winner.

Before either could happen, there was a knock at the door: A team of state troopers had arrived to protect the governor-elect. “And I never drove a car again,” Hogan says. “They took away my car, and ever since that night I’ve had guys following me around.”

***

He noticed the lump on his neck about 50 days after the riots in Baltimore. Hogan now faced his second legacy-defining crisis: cancer. The non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was in late stage III when the doctors discovered it, and Hogan’s oncologist recommended an aggressive treatment involving six rounds of five-days-a-week, 24-hours-a-day chemotherapy. The odds of survival in cases like his were between 50 and 70 percent.

The chemo sickened his stomach, evaporated his energy, and triggered numbness in his hands and feet. Clumps of hair fell out in the shower, so he shaved his head. The most painful part was the shot, to stimulate white-blood-cell regeneration, that Hogan received the day after treatment. “It felt like I got hit by a truck,” he says. “Every bone in my body hurt—the large bones, all the way down to my fingertips to my toes.”

University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore became his satellite office. State troopers were posted outside his room, and senior staffers and cabinet officials came by for meetings or to pass along stacks of documents. The steroids he received supercharged his already hyperkinetic instincts.

It felt like I got hit by a truck. Every bone in my body hurt—all the way down to my fingers, my toes.

“The steroids kept me up where I didn’t sleep for like four or five days, so I was working like crazy, working my staff to death,” Hogan says. “I was texting them all night—it was like 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 o’clock in the morning. They would wake up and go, ‘Oh, my gosh—what happened?’ ”

For exercise, the governor walked laps around the oncology floor in his sweatpants and hogan strong sweatshirt. (Fourteen laps equaled a mile, he figured out.) Along the way, he chatted up patients he bumped into. “He would come and visit the kids on the pediatric floor,” says Dr. Aaron Rapoport, the oncologist who managed Hogan’s treatment. “He became very close to many of the patients who were on the adult floor.”

Through it all, the governor posted photos—of his bald head, his new cancer buddies—to his Facebook page.

Each round of chemo got harder. “There were times where I would see him and he would admit to being pretty drained,” says brother Patrick Hogan. But on November 16, 2015, after 18 weeks of treatment, Hogan’s doctors told him his cancer was in remission. Ecstatic, he dashed back to the statehouse for a news conference. “Incredibly, as of today I am 100 percent cancer-free,” he announced. The room broke into applause.

***

There’s no doubt that Hogan’s battle with cancer endeared him to Marylanders. But voters’ memories are short, and it’s been well over a year since doctors cleared him. Throughout this time, the governor’s popularity has only increased.

For Hogan’s critics, the reason for his soaring poll numbers is simple. The governor’s entire agenda, they argue, is one big public-relations stunt, devoid of substance and designed to win him reelection. “It’s only about Hogan,” says state senator Richard Madaleno, a Democrat from Montgomery County. “It’s not about Maryland.”

Take lowering the Bay Bridge tolls, which Hogan did in 2015. The move reduced the fee, from $6 to $4, that drivers pay on the way to summer vacation spots—providing instant gratification for state taxpayers. Hogan made sure to call their attention to it with a splashy announcement and special signs at the bridge. “These little touches were great,” says Bob Ehrlich, laughing. “I’m not sure whether this was still the case, but I noticed after they changed the rates, the old rates were still up at the toll booths, reminding people what they were paying under O’Malley.”

From a public-policy perspective, the merits of Hogan’s populist maneuver are more complex. Toll cuts at the Bay Bridge and other places were expected to result in about $54 million less annual revenue for the Maryland Transportation Authority—$54 million dollars less for maintenance, repairs, or construction of new bridges or tunnels. The short-term boon, critics argued, will have long-term costs.

“The real question you would want to pose to voters is not ‘Do you want a toll cut or not?’ ” says David Moon, a Democratic delegate from Montgomery County. “It’s ‘Is that $2 difference on your beach trip worth not having repaired bridges or roads in your neighborhood?’ That’s the real choice.”

But according to Hogan spokesman Doug Mayer, agency revenues have actually increased since the toll reduction. As for the Democrats’ complaint that the governor only does what’s popular, Mayer says: “Can you imagine? I mean, oh, the horror. The utter horror of an elected official, a statewide leader, doing what the people want.”

Democrats were just as livid after Hogan appeared on the Ocean City boardwalk in sunglasses and shirtsleeves last August to, as he put it, “protect the traditional end of summer.” It was a postcard-perfect afternoon as Hogan signed an executive order mandating that public schools not open their doors until after Labor Day. As the cameras rolled, he explained that the later start date would boost the state’s economy without affecting educational outcomes.

It’s not obvious? Okay, let me state the obvious: It was pandering.

Education-policy experts weren’t impressed. University of Maryland physics professor S. James Gates Jr. resigned from the state school board in protest, saying that the decision had the “remarkable potential to damage both the most at-risk and the most ambitious students in Maryland.” Paul Pinsky, vice chair of the state Senate’s education committee and a Democrat from Prince George’s County agrees: “It’s Neanderthal thinking.”

But the critics failed to gain traction. That’s because Hogan has one key block of supporters behind him: the people. A 2015 Goucher College poll found that 74 percent of registered voters preferred starting school after Labor Day. As a result, the maneuver has put the governor’s opponents in the awkward position of battling a “common sense” reform that nearly three out of four Maryland voters support.

“It’s not obvious?” complains Pinsky, the state senator. “Okay, let me state the obvious: It was pandering.”

Hogan’s spokesman argues that Democratic leaders have supported the idea. As for the claim that it’s Neanderthal thinking: “Did someone actually call 70 percent of Marylanders Neanderthals?” says Mayer.

Hogan has also managed both to roil professional Democrats and to sway regular voters with a tactic that directly contrasts with his attention-getting reforms: “primarily by not doing very much,” as American University professor David Lublin puts it. Unlike other Republican governors, Hogan has sidestepped social-policy land mines, calling same-sex marriage, abortion rights, and gun control “settled law.” He hasn’t pursued radical tax reductions, and instead of supporting Donald Trump for President, he cast a write-in vote for his 88-year-old father. In the Democrat-controlled legislature—with which Hogan has often clashed—the governor hasn’t pursued the kind of sweeping legislative agenda that gets etched into marble.

“If you’re not doing big things,” Lublin says, “you’re not annoying a lot of people.”

Hogan’s team argues that his term has been full of accomplishments: closing the notorious Baltimore jail, strengthening drunk-driving laws, preventing tax increases, and holding the line on state spending.

Still, in 2017, not annoying people is a good strategy for a Maryland politician. The state’s economy has improved since the recession, and residents feel more optimistic about its direction than Americans feel about the country’s. “Something is happening in Maryland that people are happy about,” says Mileah Kromer, a political scientist and pollster at Goucher College in Baltimore. As long as residents remain confident about the state’s future, Kromer says, he’ll remain popular.

Hogan’s appeal is matched by a similar governor: Charlie Baker of Massachusetts. Like Hogan, he’s a Republican heading a liberal state. “Neither of these guys are sort of national-mold Republicans,” says St. Mary’s College political-science professor Todd Eberly, “and I think in a time of really intensely polarized politics, it suggests that people actually do have an appetite for folks who don’t feel as if they are going to be defined by their party’s label.”

***

In mid-October, about 50 state delegates, all Democrats, gathered in Annapolis for their regular caucus meeting. After senior lawmakers had updated the members on upcoming legislative matters, the caucus chair opened the floor to the rank and file.

That’s when Charles Sydnor III, a delegate from Baltimore County who rarely spoke at these meetings, raised his hand, according to three people in attendance. “When I go around my district, there are people who like [Hogan],” Sydnor said. “And the question for us is: How do we address that moving forward?”

It was the question many in the room had been pondering. With Hogan at the midway point of his term, figuring out how to strip off his shine has become a priority.

According to Herbert Smith and John Willis’s book, Maryland Politics and Government, Republicans as of 2010 had quietly taken control of 50 percent of seats in Maryland’s local government bodies such as county councils. And the winner of the 2018 gubernatorial election will oversee a redrawing of the state’s electoral maps after the 2020 Census. A Hogan victory, says Eberly, could allow Republicans to eliminate the Democrats’ supermajorities in the legislature—and rebalance the congressional delegation, which currently has seven Democrats and one Republican.

Thus for Democrats, the next election has higher stakes than just denying their opponent one more term— yet this opponent is much trickier than the Republicans they faced in the past.

At the caucus meeting in Annapolis that day, no one knew exactly what to do. Some suggested trumpeting more loudly the Democrats’ legislative achievements. Others argued for drawing a clearer distinction between the governor’s agenda and their own. Still others recommended the playbook that Democrats had used so effectively during the Ehrlich years: attack, attack, attack. But on what? Even Hogan’s cuts to the budget have been modest.

One of the concrete proposals they had previously discussed involved some reverse engineering. The Democrats could pass a new bill on paid sick leave—forcing the governor to take a stand on an issue that often divides Democrats and Republicans.

Before they could act, however, Hogan beat the Democrats to it. In early December, he announced plans to introduce his own sick-leave bill requiring companies with 50 or more employees to offer full-time workers five paid health-related days off annually.

Forget whether paid sick leave is good public policy, whether it should apply to companies with 50 workers or 15—Hogan had outmaneuvered the Democrats yet again. The legislature will get their fight, but the governor can now claim the middle ground and dictate terms of the debate.

And that right there is the most surprising thing about this failed congressional candidate turned small businessman turned second-most popular governor in America, Larry Hogan. Behind the beer gut and the one-liners, the snow cones and the belly laughs, is one hell of a politician.

Crim says that when he first began working at Change Maryland, a friend pulled him aside with a question: “Why in the world is Larry Hogan working with you? He’s like the best political tactician in the state and has been for 20 years. What do you offer?”

Crim’s response: “I’m along for the ride.”

Senior writer Luke Mullins (@lmullinsdc on Twitter) can be reached at lmullins@washingtonian.com.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)