In February 2012, Celia Moore opened an e-mail from a man looking to rent a room in her Portland, Oregon, home. “Friendly toward all,” he wrote. “No criminal history.” The man introduced himself as a retired police officer relocating from New Mexico and Montana. His name, he said, was Don Morsette.

Moore, a 67-year-old former paralegal with a Portlandian love of NPR and a bookshelf full of Ursula K. Le Guin, owned an old Victorian farmhouse in a blue-collar neighborhood. When Don visited for an interview, she found him pleasant and chatty. He had a thicket of dark hair that rose from his forehead and looked as if it had seen its share of dye. When he offered to pay in cash, Moore declined but was unfazed. Her boarders often strayed from convention—“They’re living a different life,” she says.

Don proved to be a well-mannered tenant, and the stories he told hinted that he was more worldly than he looked. He said he was part Chippewa-Cree and mentioned a terrible divorce. She could tell when he awoke because she could smell the Bengay he rubbed on his knee—he said he’d been a great dancer before injuring it while kickboxing. During the day, he left the house, saying he was a consultant with Boeing. “I didn’t give a rip what he was doing as long as he had his rent,” Moore says. Over time, Don told Moore about his years as a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer.

Then, about two months into Don’s stay, Moore was in bed and heard her dog growl. One of her other housemates came in. “We have a situation,” he said.

Downstairs, Moore found ten or so US marshals and Portland police officers in her living room. The head marshal introduced himself, then asked about her housemate Don—whom they had just arrested outside her front door.

Moore, concerned, asked if Don was okay.

“Well,” the marshal replied, “Don isn’t Don.”

Moore’s boarder didn’t work for Boeing. He was not a former cop, Native American, or divorced. And he’d been wanted on multiple felony charges for a year and a half.

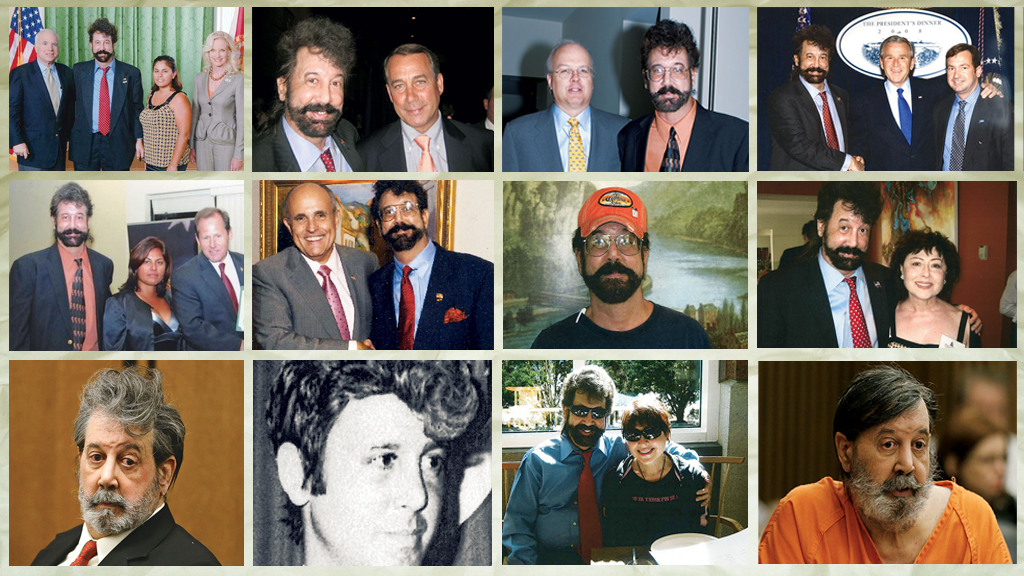

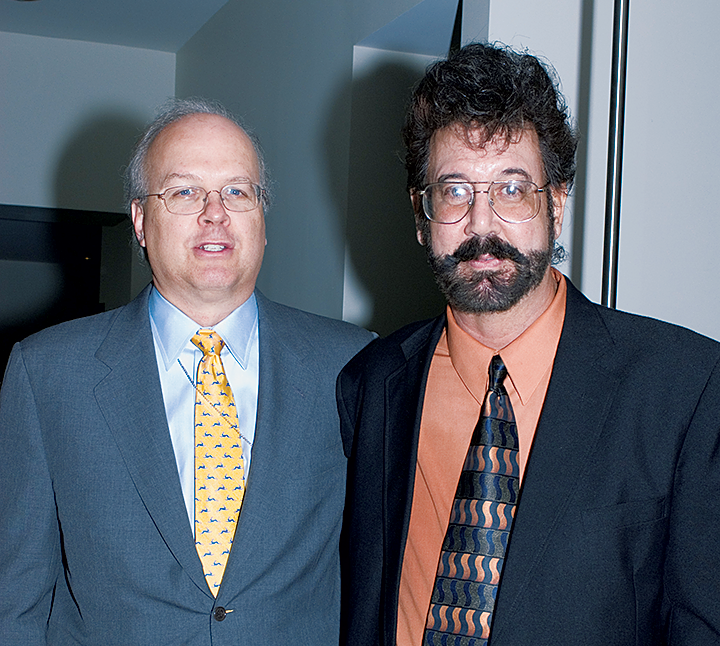

For nearly a decade, Don, it turned out, had been known as Bobby Charles Thompson—supposedly a retired naval commander. A prolific political donor, he’d posed for pictures with the likes of John Boehner and George W. Bush. At the time, Thompson was the public face of a Washington nonprofit called the United States Navy Veterans Association.

Prosecutors, however, believed that his group had defrauded donors out of about $100 million. And in the same way that Moore had learned Don wasn’t Don, the authorities had learned Bobby wasn’t Bobby, either.

When the marshals searched his backpack that night, they found three wallets, each stuffed with debit cards, scraps of paper, and IDs suggesting he was Kenneth D. Morsette, Alan Reace Lacy, or Anderson Yazzie. Other materials identified him as Lodi Gene Bitsie, Dale Booqua, Richard Overturf Jr., Anatoly Volokhonskiy. He was a specialist at Interstate Storage Rentals Inc., a security expert at LaRouche et LaRouche, a consultant at Guiness Records Ltd.

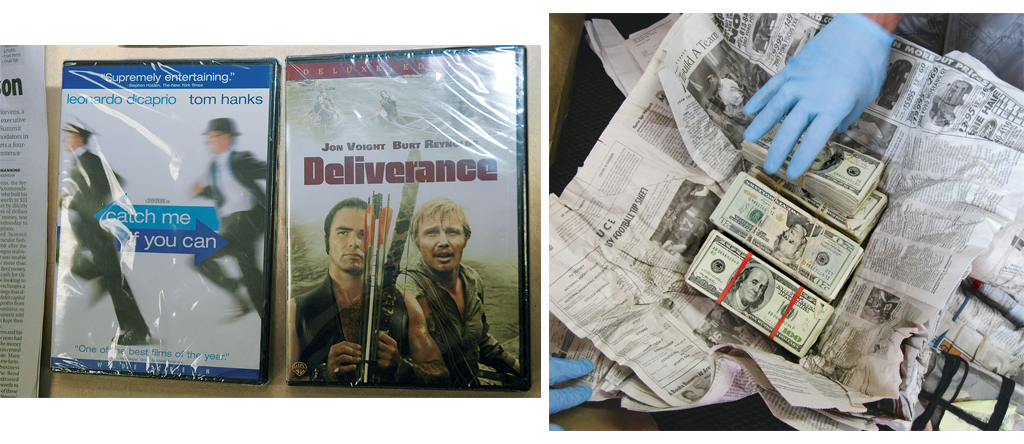

In a storage unit he rented, investigators found a suitcase full of other people’s documents: driver’s licenses, birth certificates, credit reports. Another contained newspaper-wrapped bricks of cash totaling more than $981,000. Also among his possessions were eight pairs of nonprescription glasses, more than 200 passport photos showing him disguised by various haircuts and facial hair, and a DVD of Catch Me If You Can, in which Leonardo DiCaprio plays the serial con man Frank Abagnale.

“It was like living in a movie,” Moore says. But now investigators had to figure out who the star actually was.

At the height of his powers, Bobby Thompson cut a different figure from the man arrested outside Moore’s home. With a fake-looking dark pompadour and a bushy beard, he went by “Commander,” and his nonprofit raised money at astonishing rates. Founded in 2002, the Navy Veterans Association claimed to help needy vets and servicemembers. Its website, heavy on Stars and Stripes and animated GIFs, spoke in a voice tinged with post-9/11 belligerence. “We face new enemies,” it declared. “Now we need to wake up.”

The group outsourced fundraising to telemarketing firms. Their employees collected money from good Samaritans all over the country, who wrote checks of tens or hundreds of dollars to help those who served America. By 2009, the association had 41 state chapters, plus its DC headquarters. It boasted of “66,000+ voting members,” and disclosures filed with the government suggested that, over the seven years since its launch, total revenues were roughly $100 million.

Like the Navy Veterans, Commander Thompson himself channeled a rabid patriotism. “He was a zealot,” says Helen Mac Murray, a lawyer who worked with the nonprofit from 2007 to 2010. “There was no such thing as a telephone call that lasted less than an hour.”

Nor was Thompson content to operate behind the scenes. Though he lived in Tampa, he was a frequent presence in Washington. He donated to the 2008 campaigns of John McCain and Rudy Giuliani, and to Mitt Romney and Elizabeth Dole. He reportedly attended the 2008 Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota, and he gave more than $35,000 to the campaigns and victory committees of Congresswoman Michele Bachmann and Senator Norm Coleman. In less than three years, his checks to the National Republican Senatorial Committee totaled $45,000.

Locally, he hired lobbyists in Virginia and donated to delegates William Howell, Chris Jones, and Thomas Gear; state senator Patsy Ticer; Governor Robert McDonnell; and attorney general Ken Cuccinelli, who in 2009 received more than $55,000.

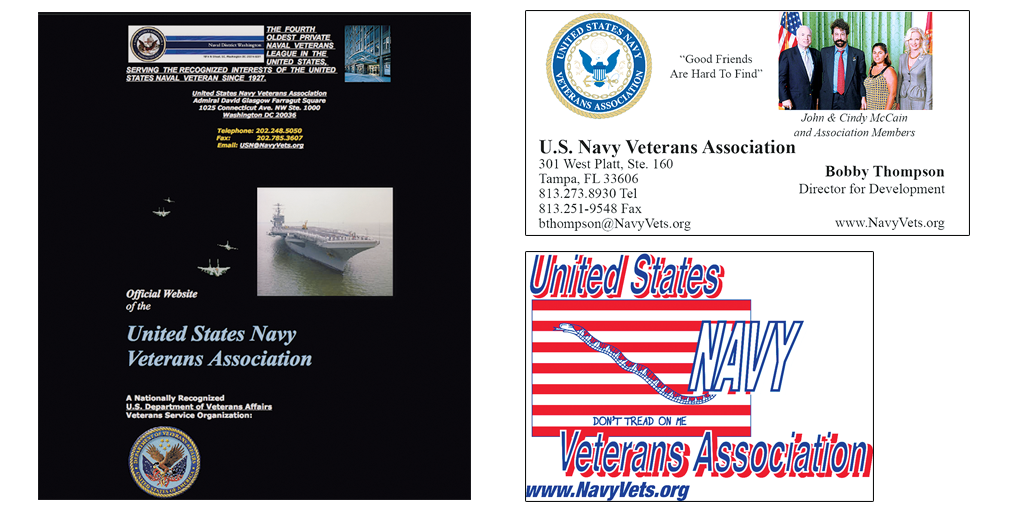

All along, Thompson appeared to revel in the public part of being a political money guy. He gave his dentist three coffee mugs decorated with a photo of him shaking hands with George W. Bush. He even featured the two of them on a holiday card. “Best wishes,” it read, “from your friends Bobby and George.”

Mac Murray received her own special memento from Thompson. She helped the group with government relations remotely from Ohio, and she didn’t meet the “Commander” in person until about a year into their relationship. She was atop Seattle’s Space Needle, at a fundraiser for Washington state’s attorney general, when suddenly a man with a pompadour and wearing a brown 1970s-style suit introduced himself as her client. He asked her to pose for a photo with him. A framed print later arrived at her office, perhaps three feet tall.

He’d show you a note from Karl Rove, so it led you to believe he had influence.

Mac Murray thought Thompson was strange, but as a proud Republican with family who’d served in the Navy, she believed in what he stood for. “The association was a referral from one of my existing clients,” she says, “so that gave it a credibility.”

That seemed to be the consensus among political types, too: Thompson may have been unusual, but he also resembled a legitimate success. “He’d show you a note from Karl Rove, or he’d show you a picture of him with some senator, so it led you to believe he had influence,” says Barry Edwards, a political consultant who spent time with Thompson in Washington. “I just thought he was a nice guy who was a kook. And I think that’s the brilliance of his con.”

The twisting route to Thompson’s arrest began with an investigation that had nothing to do with him. Jeff Testerman, an investigative reporter at the St. Petersburg Times, was writing a story about a county official he believed had lied about his military record; the man’s campaign documents listed a check from the Navy Veterans. Testerman figured he’d find Thompson at home, tell him about the man’s past, and leave with a good quote.

He walked up to Thompson’s Tampa duplex one morning in August 2009. A Bush/Cheney sticker was in the front window, and a man out front was talking on a phone. “Send it to my attention,” Testerman heard him say. “Commander Bobby Thompson.”

Testerman asked about the contribution. Thompson, he recalls, had seemingly been drinking. He grew suspiciously agitated by Testerman’s questions and denied that his association made political contributions. Eventually, Testerman asked him for his military rank. Thompson replied—lieutenant commander, Navy Reserve, retired—and then stormed inside.

Testerman had been with the newspaper 30 years, and he considered himself the sort of journalist who tried to “build a case and, honest to God, send people to jail.” Now, investigating a minor fraud, he suspected he had stumbled into a bigger one. “I came back with nothing more than a reporter’s gut feeling,” he says—that Thompson “frankly did not come across as what he is supposed to be.”

Testerman dug in. He tried to confirm that Thompson had actually worn a uniform. The federal government told him that no such records existed. He called the Navy Veterans’ headquarters incessantly, trying to reach its chairman, Jack Nimitz, and its secretary, Brian Reagan. No one called back. With a researcher, John Martin, Testerman searched for 85 directors, officials, and auditors listed on forms filed with the IRS. They verified the existence of only one: Bobby Thompson.

They also discovered that the addresses of many of the group’s state chapters were simply PO boxes. Its Washington headquarters—1718 M Street, Northwest, #275—was a rented mailbox at a UPS Store.

When Testerman sent questions to the Navy Veterans, it flooded him with hundreds of pages of e-mails, many of them signed “Brian Reagan” and alleging a left-wing conspiracy. A single 29-page message criticized Testerman’s “vendetta,” “shilling,” and “pants-on-fire stuff,” calling him “a draft dodger,” “Mr. Pulitzer Prize wannabe,” “Mr. Former Paparazzi Photographer,” and “Jeffy.”

Helen Mac Murray helped Thompson defend himself, telling the newspaper that the association had “accomplished major, specific, quantifiable achievements” and would “not lightly permit itself to be disparaged.” Still, there had been a curious episode around the time Testerman came along. The IRS had initiated an audit of Thompson’s Connecticut chapter. When Mac Murray met him to prepare, she says, his hair was untamed, his T-shirt was caked with dirt, and he smelled of alcohol.

The chapter’s documents were just as shocking. Although the Navy Veterans’ website amounted to more than 2,500 pages, key Connecticut records were nonexistent—destroyed in a flood, Thompson said. Many receipts he presented were from Tampa. Some were simply handwritten notes alongside the misspelled names of Connecticut cities—“New Havin,” “Waterberry.” Numerous purchases didn’t seem like actual aid: hair dye, rat traps, a McDonald’s hot-fudge sundae.

Nonetheless, after a meeting with the IRS in a rented office near DC’s Farragut Square, the Navy Veterans passed the audit.

As far as Mac Murray could tell, the nonprofit was legitimate, run by a robust leadership team of a dozen people. She had never met them, but she had received their memos and corresponded with them by e-mail. So when it came time to field Testerman’s questions, Mac Murray was skeptical. If he was right—if there was just one person behind 12 senior leaders, 41 chapters, and a 2,500-page website full of annual reports—she was living in an unfathomably elaborate farce.

Thompson told her to have a private detective investigate him. Surely no actual con artist would do that.

The detective’s report only raised more questions, though. It confirmed that Thompson had no military record and noted that a Social Security number provided by him belonged to a William J. DuPont Jr.

Mac Murray says Thompson told her he could explain. Over Bloody Marys at a breakfast meeting, he described how he had enlisted in the Navy using a relative’s name. He also said he was in military intelligence—and that the Navy Veterans received funding from a secret CIA budget. He suggested that people were watching or following them. “I thought he was nuts,” Mac Murray says.

But she stayed on. Officially, her client was the nonprofit, not Thompson.

In March 2010, Testerman and Martin finally began publishing their exposés: MULTIMILLION-DOLLAR NONPROFIT CHARITY FOR NAVY VETERANS STEEPED IN SECRECY, the first headline read. The reporters revealed the nonexistent headquarters and chapters, the fact that “in the end, the searches for people and documents all came back to one man.” They did note that in 2008, the association gave about $27,000 to several legitimate groups. But they also reported that since 1999, Thompson had personally spent about $200,000 on political causes and had used a political-action committee to spend another $100,000. It was a lot of money for a man whose association paid him no salary.

“The nonprofit declined to reveal where its millions of dollars in income went,” the reporters said. There was another bit of news: Thompson had abandoned his duplex. He was on the run.

Mac Murray met Thompson only one more time. At a hotel in New York, they tried to reassure the president of Associated Community Services, Thompson’s main telemarketer, that the nonprofit wasn’t a scam. Yet again, Mac Murray was disturbed by Thompson’s appearance and demeanor. ACS severed the relationship. Mac Murray, too, decided to cut ties. She flew home and hired a lawyer.

Within days, Mac Murray prepared to cooperate with law enforcement, and Thompson was recorded by a surveillance camera in New York, a baseball cap concealing his hair.

The headlines in the St. Petersburg Times caught the attention of attorneys general around the country. Eventually, Richard Cordray, Ohio’s AG, took the lead. The Navy Veterans, he alleged, was “a sham charity.”

The state had learned something Testerman hadn’t: To rent a mailbox, Thompson had used the credentials of a Choctaw Indian living outside Seattle—the real Bobby Thompson he had been living as for years. The nonprofit con man, Ohio came to believe, was also an identity thief. “We don’t know who this individual is yet,” Cordray announced. “But we do know that he is not Bobby Thompson.” The manhunt was on.

As state investigators searched, they began talking to Thompson’s alleged victims—people such as Judith Roberts, an Ohio library worker who gave about $235 after receiving a call at home, and Patrick Bray, a semiretired physician outside Cleveland who contributed $300. “The Navy paid for my medical school,” Bray stated. “Just the words ‘US Navy Veterans’ sort of struck a chord in me, even though I had never heard of them.”

A New York Republican donor named Grace Glatstein spoke of Thompson arranging a visit to the White House for her in 2007. Every security person there knew him, she said, and when she and Thompson posed for a photo with George W. Bush, Thompson playfully punched the President in the arm. No one intervened.

“I can’t believe you haven’t caught him,” Glatstein told her interviewer.

“Um, I know,” the interviewer replied. (Thompson possessed the real Thompson’s Social Security number and presumably used it to get past the Secret Service.)

In the fall of 2011—more than a year into the manhunt—US marshals in Ohio joined the investigation. A small team flew to Seattle to interview the real Bobby Thompson, which led to days of showing around the impostor’s photo. By then, other stolen identities had surfaced, and the marshals interviewed a second man whose identity had been taken—Ronnie Brittain—and the family of a third, Elmer Dosier. They hit dead ends everywhere.

Deputy marshal Bill Boldin, the team’s leader, had spent two decades in law enforcement, starting as a local cop. The task force he belonged to had arrested more than 26,000 people. But he had never worked a case in which he didn’t know the suspect’s name. After his men spoke with Dosier’s family, he became more determined to find Thompson. Dosier had been a police officer, killed in the line of duty. To Boldin, it was as if Thompson had chosen him as a taunt.

By February 2012, the team had learned of another stolen identity: Lance Guy Martin. He had addresses on a reservation in New Mexico and in Providence, Rhode Island, but the tribal police said Martin had never been on an airplane. So the marshals flew to Providence and found Thompson’s landlord. Thompson, he said, had been gone for a few months and had left his apartment in a rather unusual state. When the landlord walked in, it contained a pulpit, chairs, and religious paraphernalia. As a fugitive, Thompson had tried to start a Christian charity.

The marshals were disappointed, but they did learn something useful in Providence. While Thompson had lived there, he’d bought prepaid debit cards using the name Anderson Yazzie—a name associated only with a couple of Navajos. Some of the cards, they discovered, had recently been used in Portland, Oregon.

Boldin’s team arrived in Portland on a Monday, intending to stay as long as it took. But that evening, Boldin entered a quiet pub to which they’d traced some of the transactions. He took a seat at the bar. Then he texted his colleagues: I think he’s sitting right next to me.

At first, Boldin’s partners thought he was joking, but Boldin was insistent: On the stool closest to the door, drinking a tall draft beer, was a man who looked like an older, slightly rundown version of the man Boldin had seen in pictures shaking hands with President Bush.

What stood out most was the hair: full and fake-looking.

The men decided to follow Thompson home. Within a half hour, about ten plainclothes marshals and police officers had gathered discreetly outside the bar.

Thompson left and walked to a supermarket. He got onto a motorized shopping cart and began driving down the aisles while a member of the squad watched on the store’s surveillance cameras. At one point, someone stationed outside noticed a motorized cart by the loading dock. Everyone panicked. It turned out Thompson was still inside, too low for some of the cameras.

By now it was past 10 pm, and Thompson made his way to a residential block nearby. Suddenly he turned and looked at the parade of unmarked vehicles following him.

we don’t know who he is yet. But we do know that he is not bobby thompson.

The marshals had contemplated what it might look like when they finally ended Thompson’s life as a fugitive. Would he become violent? Try to run?

Instead, as men in bulletproof vests surrounded him outside Celia Moore’s house, Thompson was calm. Boldin heard him say “Fifth,” invoking his right to remain silent. “It was highly uncharacteristic,” Boldin says. “He wasn’t happy, he wasn’t scared, he wasn’t pissed off. Nothing.”

In hindsight, that blankness fit everything Thompson did. “He was a professional criminal,” Boldin says. Being arrested was “like another day at the office.”

But arresting the man in Portland didn’t solve the mystery of who he really was. In September 2012, as Thompson sat in an Ohio jail, investigators got a break from an unlikely source: Google.

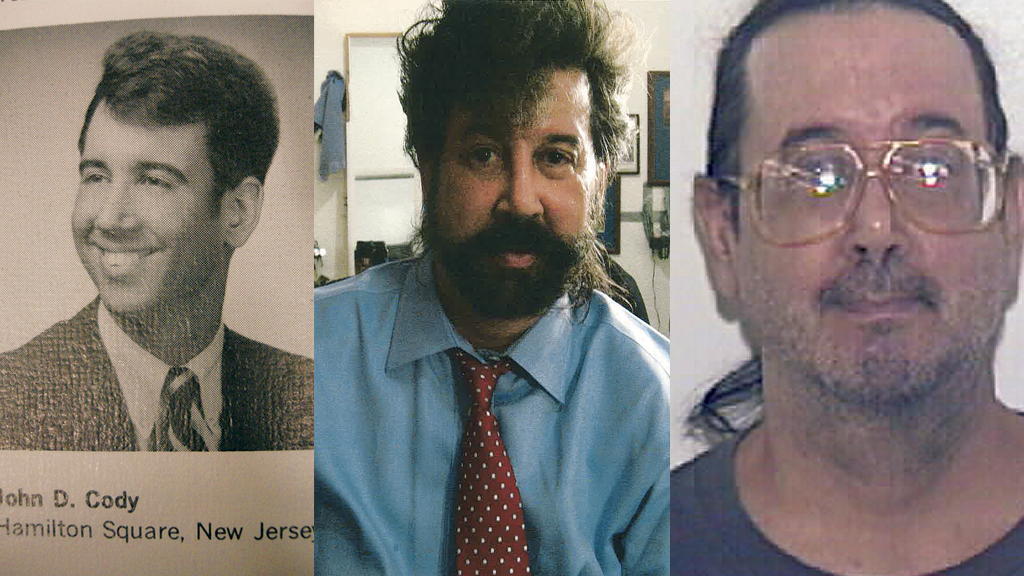

Over the previous five months, investigators had taken his fingerprints but hadn’t gotten a hit. The prosecution sought palm prints, DNA testing, handwriting analysis. Nothing helped. So Boldin’s boss, Pete Elliott, turned to the search engine. He Googled terms such as “major fraud fugitives” and found a Business Insider article headlined the 10 most intriguing white collar fugitives. Number two was a man named John Donald Cody.

The article linked to an FBI wanted poster. Cody, a lawyer, had been on the run since 1984, when he fled Arizona and was charged with theft and fraud. He spoke Italian and the Filipino language Tagalog. He was wanted for questioning in connection with an espionage investigation. And he reportedly did not have tear glands—in other words, literally couldn’t cry.

Via Google Images, Elliott found a photo of a young Cody in a military uniform. He stared at the hair on his screen: a thick Thompson-style pompadour.

The FBI had theorized that Cody might be in the Philippines. Nonetheless, the Bureau forwarded his fingerprints, which came from the State Department and strangely weren’t included in the FBI’s database. They were identical to Thompson’s.

Soon after, Elliott visited Thompson in jail, carrying a copy of the wanted poster.

“I threw it down in front of him,” Elliott recalls, “and said: ‘John Donald Cody, your time is up.’ He had a little smile on his face, and that’s about it.”

Cody’s actual biography, the team would learn, was more interesting than Bobby Thompson’s or Don Morsette’s. Born in 1947 in Hoboken, New Jersey, he was indeed a veteran—but of the Army, not the Navy. He enrolled in ROTC at the University of Virginia, then attended Harvard Law, juggling classes with airborne and ranger trainings. After graduation, he served in military intelligence.

According to Cody’s military file, he worked in Angola in 1969 on behalf of the March of Dimes, supported Pete McCloskey’s anti–Vietnam War bid for the 1972 Republican presidential nomination, and was a “white mercenary” in the Congo. From 1972 to 1979, according to a statement of personal history he wrote, he worked at law firms in Honolulu, Manhattan, and New Orleans; joined Weyerhaeuser, a timber company, in Washington state; and studied for an MBA in the Philippines. (Other documents in the file are consistent with this account.) Simultaneously, his file shows, he was an Army Reserve intelligence officer. He was trained to do much more than gather information: He studied “civil disturbance,” “nuclear weapons employment,” and counterinsurgency techniques used covertly in foreign states.

Cody’s last residence before he fled was Sierra Vista, Arizona, where he practiced law in the early 1980s. Its Army base reportedly served as a headquarters for covert operations in Central America.

“He was an anomaly,” recalls Paul Rubin, then a reporter with the local paper. There was, of course, the hair: “It looked regular, and then all of a sudden it went up in the air, almost like a French courtesan.” But also the skin—“a very odd, Donald Trump–ish skin tone.” In a border town of pickup trucks, Cody drove an orange Corvette.

He represented many indigent clients, advancing ideas so far out that one judge wondered if he had studied law. He had an anarchic, libertarian toughness, at one time stating that people should never be charged with crimes at all. He claimed a prosecutor wanted to “physically eliminate” him.

It was during this period that Rubin received an intriguing tip: that Cody was stealing from the estate of two deceased clients. Rubin confronted Cody at home. “His bedroom was just one little bed,” he says, “and a light on a stand, and near his bed two neat piles: one pile of law books, and Playboy magazines piled 25 or 30 high.”

Rubin says he published the theft allegations, which Cody denied, and recalls that Cody effectively went underground. Then, early one morning, Rubin drove by Cody’s office and saw him through a window. Cody spotted Rubin, too. “He takes off out the back door—he’s literally running,” Rubin says. “I say, ‘John, John, John!’ And he gets into his Corvette.”

It was May 22, 1984, Cody’s first day of nearly 28 years as a fugitive.

Two months later, law enforcement found the Corvette at the Phoenix airport with the keys in the ignition. A grand jury indicted him on theft and fraud charges, determining that Cody did steal about $100,000 from his clients. Arizona disbarred him. Initially, he left a trail, allegedly using false tax documents to establish fraudulent identities and seek a loan in Virginia, where he said he was an investment adviser to clients in Mexico and Kuwait. Then he disappeared.

Investigators reportedly came close to catching him several times, tracking him to Mexico and California. (A spokeswoman for the FBI in Washington would not comment on Cody’s activities.) The Arizona Republic reported that his pursuers once entered a storefront only to find that Cody had just beaten them out the door.

In 1997, Cody’s mother—who believed that the government wanted to “make him disappear,” in the words of a relative interviewed by the Tampa Bay Times—petitioned a Florida court, along with his sister, to have him officially presumed dead. (Cody’s mother is deceased. His sister didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

A few months later, someone using the name Bob Redbear founded a security company in Portland, Oregon. Among the people who applied for jobs there were Kenneth D. Morsette, Alan Reace Lacy, and Anderson Yazzie—the men whose names appeared in the three wallets of Celia Moore’s boarder. The firm dissolved in 1998. Around the same time, in Tampa, a Bobby C. Thompson registered to vote.

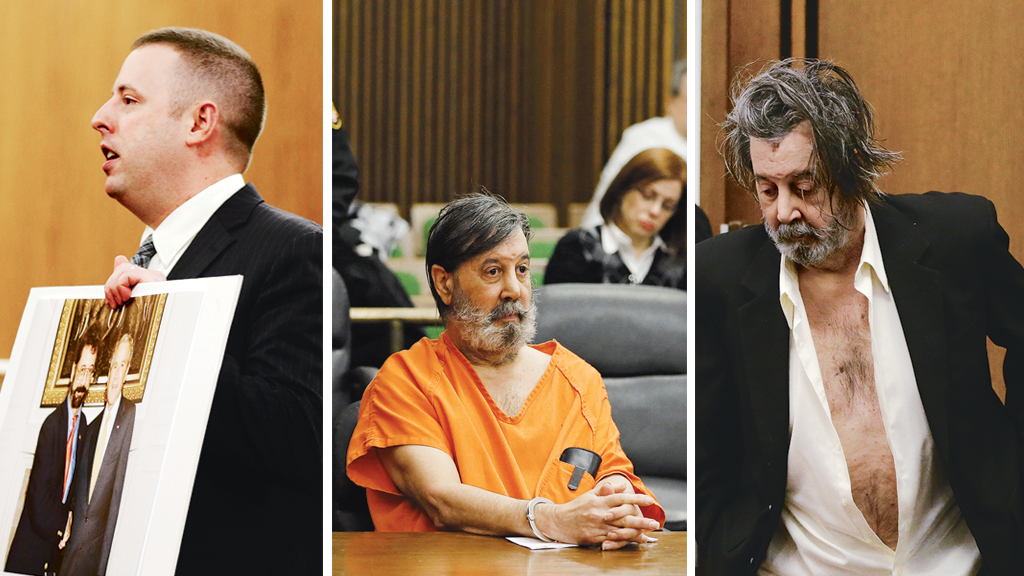

The trial in the State of Ohio vs. Bobby Thompson, a.k.a. John Donald Cody, began October 7, 2013. Wearing a suit, Cody listened as the lead prosecutor, Brad Tammaro, posited that Cody’s decades of crime had begun when he was passed over for promotion in the Army. “He is John Donald Cody,” Tammaro said. “And what the evidence will show you is that he is simply a thief—a thief that could not tell the truth.”

Cody’s attorney, Joseph Patituce, sketched out an alternate theory of the case for the jury: “I want you to look at the government and ask them: Who was he from 1984 to 1999?” He lingered on the mysterious absence of Cody’s fingerprints from the FBI’s database—something the marshals had also found puzzling—and concluded that Cody was no criminal. He was, Patituce argued, a man who had served his country.

“How does he get that close to the President?” Patituce asked. “And no offense to my client, but he is someone who kind of stands out, just looking at him.”

Patituce seemed to be alluding to a scenario that Cody had laid out in lengthy pretrial filings, a theory for his motivations that gets at the least understood aspect of his biography: John Donald Cody claims to be a former employee of the CIA.

He said he became a “non-official cover” agent secretly furthering American interests—via charities and nonprofits including, he implied, the Navy Veterans Association. He said he intended to call as witnesses more than 40 alleged operatives, politicians, and Navy Veterans associates, including David Petraeus, Eric Holder, and Barack Obama. Finally, he asserted that US intelligence agents had subjected him to hypnosis and psychotropic drugs to establish or maintain his various covers.

As far-fetched as certain of these claims may sound, Cody’s military file does contain a top-secret security clearance approved in the 1970s by an unnamed “federal agency other than Department of the Army.” Other details suggest he belonged to a clandestine CIA command that trained military reservists to deploy as operatives abroad. (The command is described in declassified documents; a CIA spokesman declined to comment on Cody’s past.)

Whatever the case, Cody’s purported life as a secret agent didn’t go anywhere in court. The prosecution mounted a weeks-long account of Cody’s con, debriefing the jury with more than 100 exhibits: the fake IDs; the contents of his room, his suitcases, and his hard drives; the actual $981,000 from his storage unit. Cody found himself listening to witnesses he may have thought he would never meet: the real Alan Reace Lacy, the real Anderson Yazzie, and yes, the real Bobby Thompson, who not only lacked the theatrical hair of the fake one but, with his dark skin, was obviously of a different ethnicity. “The gentleman right here with the beard, take a moment and look at him,” Tammaro said to the real Thompson, referring to the fake one. “Have you ever given anybody permission to use what is your personal information?”

“No,” Thompson replied.

In court, Tammaro rendered a picture of the smooth operator who liked to work rooms full of powerbrokers. But people such as Testerman and Mac Murray also testified about his other personas—the disheveled, booze-scented oddity who showed up for the IRS audit preparations, for instance. It was a version of that character who emerged as the trial neared its end. During a recess one day, loud thumps reverberated through the courtroom: Cody, in an adjacent holding cell, was banging his head against a brick wall so hard that he stained it with his blood. A week later, he showed up to court late, his forehead scabbed, his hair uncombed, and his shirt unbuttoned to his navel.

The judge asked Cody, repeatedly, if he was going to testify. Each time, Cody whispered to Patituce. Then Patituce announced: “I do believe he will not be taking the stand, Your Honor.”

Patituce soon said the defense wouldn’t be calling any witnesses. He declined to offer a closing argument. On November 14, Cody was convicted of 23 felonies.

He finally spoke at his sentencing hearing. “Just briefly, Your Honor,” Cody said. “Thank you. I understand what the court is doing by referring to me as Mr. Cody. Bobby Charles Thompson is my name.”

John Donald Cody, now 69, received consecutive sentences totaling 28 years and is imprisoned in Ohio. Filing multiple appeals, he has managed to have some of his convictions vacated and his prison term reduced by a year, but a petition he sent to the Supreme Court was denied in the spring of 2016. If he lives to serve his full penalty, he’ll be free at age 91.

The Navy Veterans scheme is thought to be one of the largest US charity frauds ever prosecuted—all the more striking because it was orchestrated by a single bad actor.

Because the prosecution’s forensic accounting focused on money stolen from Ohio residents—for the purposes of conviction, cash from other states was irrelevant—most of the $100 million the Navy Veterans said it took in remains officially unaccounted for. But agreements with Cody’s two main telemarketing firms stated that the firms kept up to 90 percent of donations. Similarly, Ohio never closely examined whether the association was a front for political contributions. All it needed to show was that money was siphoned off as personal ATM withdrawals or checks written to cash.

As with so many cases of elaborate fraud, the big unanswered question was: Why? Cody, with his rat-trap and McDonald’s-sundae receipts, didn’t live lavishly. Giving to politicians as Commander Thompson may have been his sole indulgence. (Many campaigns said later that they would donate the money to charity.) “By the time he gets up and running, he is a player, and he likes being a player!” Jeff Testerman says. “And he likes standing next to the President so damn much in the White House that he puts it on his business card.”

To Bill Boldin, Cody was a criminal of immense talent who became less careful with age. “He got older, was drinking, got sloppier,” Boldin says. “I’m not going to say anything to jeopardize the conviction, but obviously there have to be some behavioral or mental-health issues there.”

john Donald cody is my name. I was for 45 years an intelligence officer.

The person who may have sympathized most with Cody is his landlady, Celia Moore. “His mother and his sister had him declared dead,” she says. “How sad. To live your life alone like that.” After his arrest, Moore wrote him letters, and Cody wrote back about life’s “strange twists,” signing his letters “Don.”

I wrote to him, too. In January, an envelope from Ohio landed in my mailbox. The return address gave the sender’s name as Bobby Thompson.

“I wanted to get you off a quick note,” he began, meaning an eight-page letter with footnotes. He apologized for his handwriting, a soft but hard-to-read cursive. He couldn’t help describing how he’d been “deluged” by media requests for his inside story but explained that any cooperation would be limited. A prison official, he said, “has barred me ‘forever’ from media interviews.” (“She and I are not friends, to speak euphemistically.”) Besides, he added, he was trying to obtain a new trial, “WHICH REMAINS,” he wrote, “AND MUST REMAIN, THE FIRST PRIORITY OF MY SCARCE TIME AND RESOURCES.”

Nonetheless, he answered some questions, railing against what he called “the fundamental lie that I stole money from veterans.” “From the standpoint of George W. Bush’s CIA,” he wrote, “the mission of the USNVA was to influence public and elite opinion among our traditional allies”—especially Britain but also France, Israel, and others—who, witnessing “hard support” by “Joe and Jane Six Pack” in the form of small donations, would be encouraged to get behind the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the war on terror.

I wrote back, and one day in February, 15 more envelopes arrived. In them, he rambled on about “the real story” behind the Navy Veterans, quoted Shakespeare and the Declaration of Independence, and warned that powerful “enemies” were conspiring to hide the truth. But it was his first letter that stuck with me most. Throughout it all, he seemed desperate to define his identity for himself—but this time not as Don, and not even as Bobby.

He was a victim, locked up by a “biased” judge and “hit, punched, and spat upon” for his views. (Behind bars, he was “one of Trump’s biggest supporters.”)

He was an everyman, having worked “blue-collar student jobs”—cafeteria worker, brewery bottler, mailman—even as, attending “Mr. Jefferson’s university” and Harvard, he belonged to “a prestigious and honorable elite.”

And he was, he said, a CIA operative from 1967 to 2012, first assigned the name Bobby Thompson “lawfully” as a cover identity.

But he was also someone else.

“John Donald Cody is my name,” he said. “It is my birth name. I am proud of it, as I am proud I was for 45 years, and will always be, an American professional intelligence officer, and as I am proud of all my activities serving as such, including USNVA.”

Daniel Fromson has written for New York, the Atlantic, and the New York Times. He can be reached at daniel.fromson@gmail.com.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified Richard Cordray.

This article appears in the March 2017 issue of Washingtonian.