Forget about that guy who has won 15 Grammys. Whose band, Foo Fighters, has sold nearly 30 million records. The Emmy-winning director who has appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone numerous times and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as the frenetic, powerhouse drummer for Nirvana. Who has performed at the White House and on Saturday Night Live, was invited by Dave Letterman to play “Everlong” as the credits rolled on his final show—and who once jammed with the Muppets.

Let’s talk, instead, about Dave Grohl’s mom.

Virginia Grohl—Ginny to her friends—is a warm, book-loving woman with a mop of dark hair who looks younger than her 79 years, especially today, with her slash of red lipstick and bright crimson scarf. Her assistant, Joe Zymblosky, has brought several wardrobe options for this publicity shoot at the Black Cat, and he observes approvingly, occasionally jumping onto the stage to help get the look just right. Lisa, Dave’s older sister, is here, too, part of their mom’s small entourage in from Los Angeles. The entourage also includes Lisa’s cat.

Ginny has been to the DC club many times, both here and at its original 14th Street location three doors down. Dave was an investor when the place first opened in 1993, and owner Dante Ferrando, here to greet her, is an old friend. But she’s far less familiar with today’s vantage—leaning on an amp, mugging for the camera under the bright lights. As Foo Fighters cycle through tinny laptop speakers, the photographer jokes that Ginny should channel a “head-banging mom” to get in the mood. Much as the former Fairfax County teacher tries to look as if she’s having fun, she’ll later admit that the whole experience was “uncomfortable.”

Yes, she has an assistant, but being the center of attention is not this down-to-earth woman’s MO. For 30-plus years, she’s cheered on her beyond-imagination-successful son from the sidelines. Now that’s about to change—this month, Seal Press publishes her book, From Cradle to Stage: Stories From the Mothers Who Rocked and Raised Rock Stars.

It’s a collection of vignettes culled from three years of conversations with more than 18 women and, with two tragic exceptions—Amy Winehouse’s death at age 27 and Kurt Cobain’s 1994 suicide—largely a chronicle of success. But there’s a wide range of variables in the narratives—the hardscrabble Texan background of country singer Miranda Lambert and the Upper West Side private-school world of the Beastie Boys’ Michael Diamond. R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, who formed his band in college and then dropped out, and Harvard grad Tom Morello, guitarist for Rage Against the Machine. But it’s often the moms’ stories that most fascinate: Mary Weinrib, mother of Rush’s Geddy Lee, is a Holocaust survivor. Verna Griffin, Dr. Dre’s mother, watched Compton burn in the 1965 Watts riots while cradling the infant Andre in her arms.

The one constant: “All of our kids, between the ages of 12 and 13 . . . said, ‘Hello, world, this is what I’m going to do,’ ” Ginny says. For the moms, she writes in the book, “It was take it or leave it . . . and most of us took it, not knowing what ‘it’ was, and tried to hang on.”

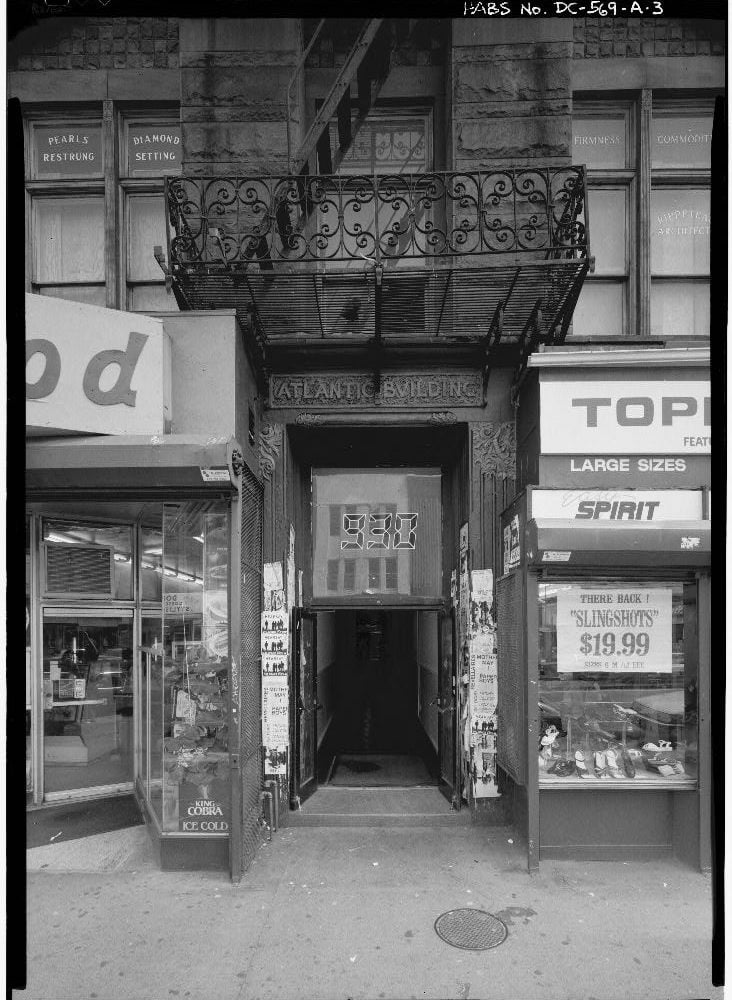

The project came about several years ago while she was hanging out at the New Orleans Jazz Festival. Ginny had always been the mom in the crowd. Sometimes she’d watch her son perform from the side of the stage, sometimes from the mosh—at the 9:30 Club, she says, she’d literally hold onto the bar to avoid getting crushed. “I knew the bartenders really well,” she laughs. But as the years ticked by and she showed up at show after show, she frequently found herself the oldest person there. Where were the other moms? “I’ve been going to shows forever and have only met about two of them in all that time.”

And that right there is what you need to know about the genesis of Ginny’s book, but it’s only a sliver of the story of the family itself.

The Grohl house in Springfield was built in the 1940s. Today it’s a modest rambler amid a landscape of houses wrapped in Tyvek, as split-levels and their ilk make way for McMansions. Ginny spends part of the year in Los Angeles to be closer to Dave and his family but still comes back to the place she and her kids consider home.

“Whenever I felt overwhelmed with the success of Nirvana,” Dave says in a phone call, “I would just go back to Virginia, to that house, to the bedroom where I grew up and the neighborhood that I walked through to school every day and all of my friends were two or three blocks away, and it helped me keep my head level.”

He describes how in the 1990s he briefly considered buying a new house for his mom, but they decided against it. This was, after all, the home where Dave used his bed (or just about anything else) as a drum set—because the house was too small to accommodate an actual set. It’s the home where, every year starting in the ’80s, Ginny hosted a party on Christmas Day, and neighbors, music buddies, and her former students all hung out over shrimp platters and layered taco spread. (During the Nirvana years, there was a bouncer checking bona fides.)

The Grohls had settled in Northern Virginia when Dave was a toddler. Always, there was music in the house. His late father, James, a former Scripps-Howard journalist who also worked in politics, was a jazz flautist. (The marriage ended while Dave was in elementary school, and Ginny raised him and Lisa largely on her own.) Ginny is a mezzo-soprano. When she was growing up outside Youngstown, Ohio, her musical revue, “The Three Belles,” was a small-town sensation. At Ohio Wesleyan University, she and a friend wrote musical skits and comedy sketches for frat houses, a passion that so occupied her she nearly flunked out of school.

Kind of surprising, perhaps, for a woman who would become an AP English teacher, but also telling about the kind of mother she would become—one who took Dave and Lisa on Sunday afternoons to the dark, smoky One Step Down jazz club in DC, who turned up the car radio and sang along with her kids. In the book’s foreword, Dave describes his “musical ‘Big Bang’ ” as the day Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain” came on and he learned how to harmonize with his mom.

Dave was around ten when he discovered the guitar and drums. As he got older, he became captivated by DC’s burgeoning punk-rock scene and, with Ginny’s permission, began venturing downtown to clubs. (He’d call her when he changed locations so she’d know his whereabouts.) He began playing in a bunch of bands—Mission Impossible, Dain Bramage. His talent was hard to miss—there are videos on YouTube, including one from a 1985 concert, that captures his exuberance. The kid is on fire! His hair flying, he throws his whole body into the kit. “One fellow told me within the last year or so that people used to come to those shows just to see David,” Ginny says. “He just slammed those drums. And he did look great playing them.” The kids’ gigs were at makeshift clubs and community centers and were supervised by moms, Ginny among them.

By the time he was a teenager, it was hard to keep him in school. He tried three high schools: Annandale, Bishop Ireton, and Thomas Jefferson, where Ginny taught at the time and Lisa was also enrolled, but often he just didn’t show up. One day when Dave and Ginny were in a music store in Falls Church, he spotted an advertisement—the hardcore punk band Scream was seeking a drummer. He auditioned, lied about his age (he was 17), and was hired.

To hear Dave tell it, his mother was no pushover. At home, she made him and Lisa run “articulation drills,” which involved speaking for two minutes on a randomly assigned topic without using words such as “er” or “um.” It’s a “cruel device,” Ginny says, one she employed in the speech classes she taught.

Yet clearly she was also able to understand that her son—a kid with manic energy who held down jobs making pizza and working at Marlo Furniture, who dabbled in just about every sport from lacrosse to soccer to ice hockey—was just not cut out for school. “I knew how smart he was. I knew what a good writer he was,” she says. “There was no reason why he shouldn’t be a great student. Except he just didn’t like it.”

So, after years of trying to keep him engaged, she stopped. When Scream invited Dave to go on tour, she sensed it was okay to let him quit school: “I’m surprised that people are surprised by it. It seemed such a good idea . . . to go to Europe.”

Her decision changed the trajectory of his life but also preserved their close relationship—which, as she notes in her book, isn’t the case in every celebrity family.

“I’ve always looked up to my mother as someone who is wise,” Dave says. “I don’t know if it’s her Southern/Midwestern charm or just her perfect grace, but she holds that wisdom in a way that isn’t intimidating or excessive. She’s just cool.”

Be cool, be wise, learn when to lean into your kid’s passions and when to grab him by the scruff of the neck and drag him to school—help channel that wild energy rather than throw up blockades. That’s the takeaway from Ginny Grohl’s book, whether you’re raising a rock star or just a creative kid you don’t want to end up hating you.

As Dave tried to make it with Scream, there were lean years, but Ginny wouldn’t find out about them until later.

“There were no anguished calls or pleas for money or a plane ticket,” she writes. “David kept in touch, but he always sounded like the cheerful, upbeat son who had left, feeding my blissful oblivion.” Soon he moved into a “squalid” Seattle apartment with Kurt Cobain to learn the music of his new band, Nirvana. “He was on the other side of the country with no money and no friends, but on the phone he seemed only upset about the cold, rainy weather. . . . Enter now the chorus of practical, realistic parents. You never should have let him go. He was too young. I could have told you this would happen.”

Yet only months after Dave joined Nirvana, the band signed a major record deal and produced Nevermind, the chart-topping album that turned its musicians into worldwide stars. Perhaps counterintuitively, this is when Ginny’s real concerns began. “The bleak days when the kids go from city to city with just enough money for hot dogs and Slurpees aren’t what mothers of the musician-adventurers fear,” she writes. “It’s that next step, the one where money and fame replace impoverished obscurity. What will all that money be used for? What and who will enter the picture once fame is the new reality?”

Certainly, the three years that Cobain’s overdoses, missed concerts, and eventual suicide captured the country’s attention were turbulent for Ginny, too, even as Dave developed an image as the “fun” member of the brooding band. (He’s been called “the nicest man in rock.”) These aren’t memories she’ll discuss. In the book, though, she periodically alludes to the pain of that period—as well as the happy moments.

“Our homes were the only safe zones,” she writes. One weekend when Nirvana played DC, the band took refuge at Ginny’s. There was beer and badminton. “I vividly recall that Kurt placed himself outside the circle, sitting quietly, slightly separate from the rest. I joined him and we talked about some of the books on the shelves behind us. I gave him my copy of Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine and urged him to read it. I have always thought it should be staged with music. . . . [W]e talked about ideas and books, not the craziness that was surrounding him. I was delighted to listen to the quiet, introspective Kurt, who smiled and conversed easily . . . .”

In 1991, Nirvana was performing at the Reading Festival in England when Cobain took the mike and announced, “Guess what? Today is Dave’s mom’s birthday. Let’s sing to her!” Of course, Ginny was there.

You might think Ginny Grohl’s life is exponentially more glamorous now, living part-time in LA, her son one of the most famous musicians in the world. You’d be right, but you’d be wrong, too.

Sure, there are seats at the Oscars and the Grammys. She has a fancy outfit that Joe helped her find, and she likes it so well she’s worn it three times in a row. “It is fun,” she says, “if I only have to do it every once in a while. But I do enjoy it.” She’s met Prince Harry and President Obama.

She’s also traveled the world with a backstage pass around her neck. “My mother got to meet every rock star on the face of the earth, and they all love her,” says Dave. He describes once emerging from the stage “a sweaty mess with a towel around my neck and she’s sitting there having a Guinness with Billie Joe [Armstrong] from Green Day.”

When she’s not on the road, the rhythms of Ginny’s days in California are pretty normal. She’s an avid reader. The rest is mostly about the kids. Her two-bedroom house in the Valley is about four minutes from Lisa and about 15 minutes from where Dave lives with his wife and their three daughters. “My social life is family dinners and events and going to the girls’ performances at their school,” she says. Dave is “a huge barbeque genius. . . . In the summer, he cooks every day when he’s home. When he’s not on tour, he’ll just call and say, ‘Brisket at 5—come over.’ ”

I come off the stage a sweaty mess with a towel around my neck and she’s sitting there having a guinness with billie joe of green day.

The bicoastal life is a privilege, but they all retain a deep connection to Washington. “I’ve been in Los Angeles for 16 years,” Dave says, “and I still feel like a transplant because my heart is in Springfield.” When they return, Ginny reactivates her subscription to the Washington Post, no matter how short the stay. She turns on her TV, looking for her favorite news team. The anchors in LA may be glamorously attired, but “they’re not Doreen Gentzler.”

Other things Ginny loved have changed, not always to her liking. When she taught at Thomas Jefferson, before it was reinvented as a magnet school (she now calls it “Hoopla High”), she could assign any book she liked—Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, say—and spend an entire quarter on it, amplifying the context with other texts, such as William Manchester’s The Glory and the Dream, a comprehensive social history of the US. She has heard that nowadays, a book is assigned on Monday, a test is on Friday, and there’s no time for discussion.

(Fun fact: Former student Jason Gavin once punted on writing a report on Othello and instead produced, with a friend, what he describes as a defiant rap. Rather than punish the kids, Ginny had them perform it for her other students. Gavin is now a successful film and television writer in LA whose credits include TV’s Friday Night Lights.)

Still, Ginny is happy to bring Dave’s daughters back to Virginia now and then, to show them where their dad grew up. The home holds Lisa’s stained-glass art and family memorabilia. Out back, there’s the yard where she liked to garden, although talking about this reminds her of the year Dave and his friends ripped it up with his go-cart. That was an acquisition Ginny remembers resisting until, like being worn down about high school, she finally gave in.

“From when he was three, here’s what’s true,” she says. “He always got what he wanted.”

Susan Coll is a novelist in Washington whose work has appeared in the New York Times and Washington Post. She can be reached at collsusanj@gmail.com.

This article appears in the May 2017 issue of Washingtonian.