During the Cold War, Americans thought of the Soviet Union as an endlessly grim place. Nothing symbolized the land of not-plenty more than a long line of human beings in single file. Dental floss, chicken, bicycle seats—what was at the other end didn’t matter. Those long-suffering Brezhnev-era proles would have to accept their lot. By contrast, here in the land of the free, anyone could drive to Walmart and buy a year’s supply of toilet paper—and a couple of wheelbarrows to cart it home. Liberty meant not lining up like a bunch of sheep.

These days, consumer goods are apt to come straight to the house, freeing us from the hassle of even a run-of-the-mill wait at the Target checkout counter. But in certain culturally forward corners of Washington at least, we’ve had a distinct change in our attitude toward lines. They’ve become a sign that you’re one of the cool kids.

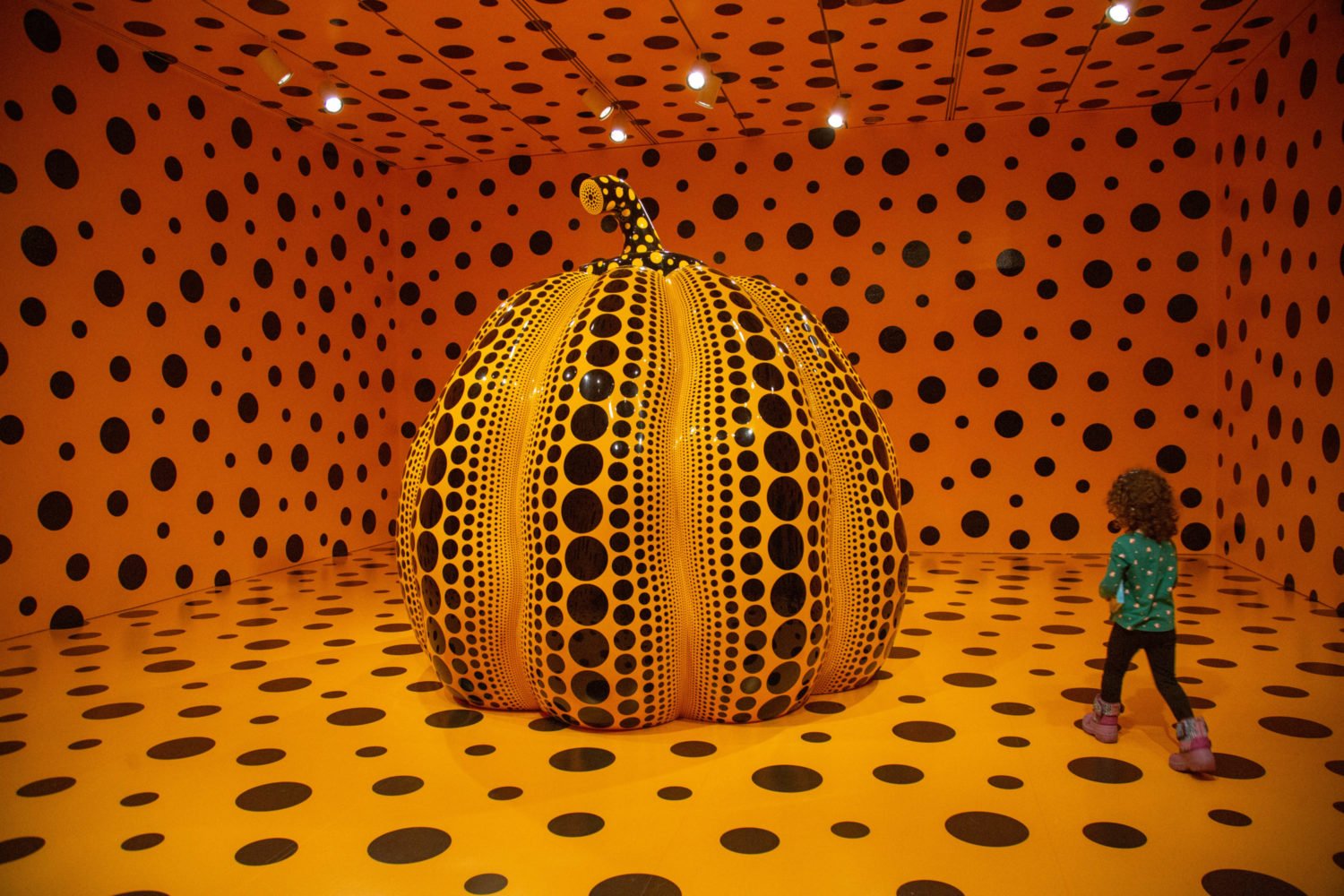

At envelope-pushing restaurants such as Rose’s Luxury, the waits can run hours for meals that might run upward of $250. At of-the-moment watering holes such as this spring’s cherry-blossom-inspired pop-up bar in Shaw, the throng of would-be drinkers of $13 cocktails snaked around the corner. Even with timed-entry passes, a trip to the Hirshhorn’s “Infinity Mirrors” show, which closed in mid-May, generally involved an infinity of standing around before being hustled through the startling exhibit. The list goes on.

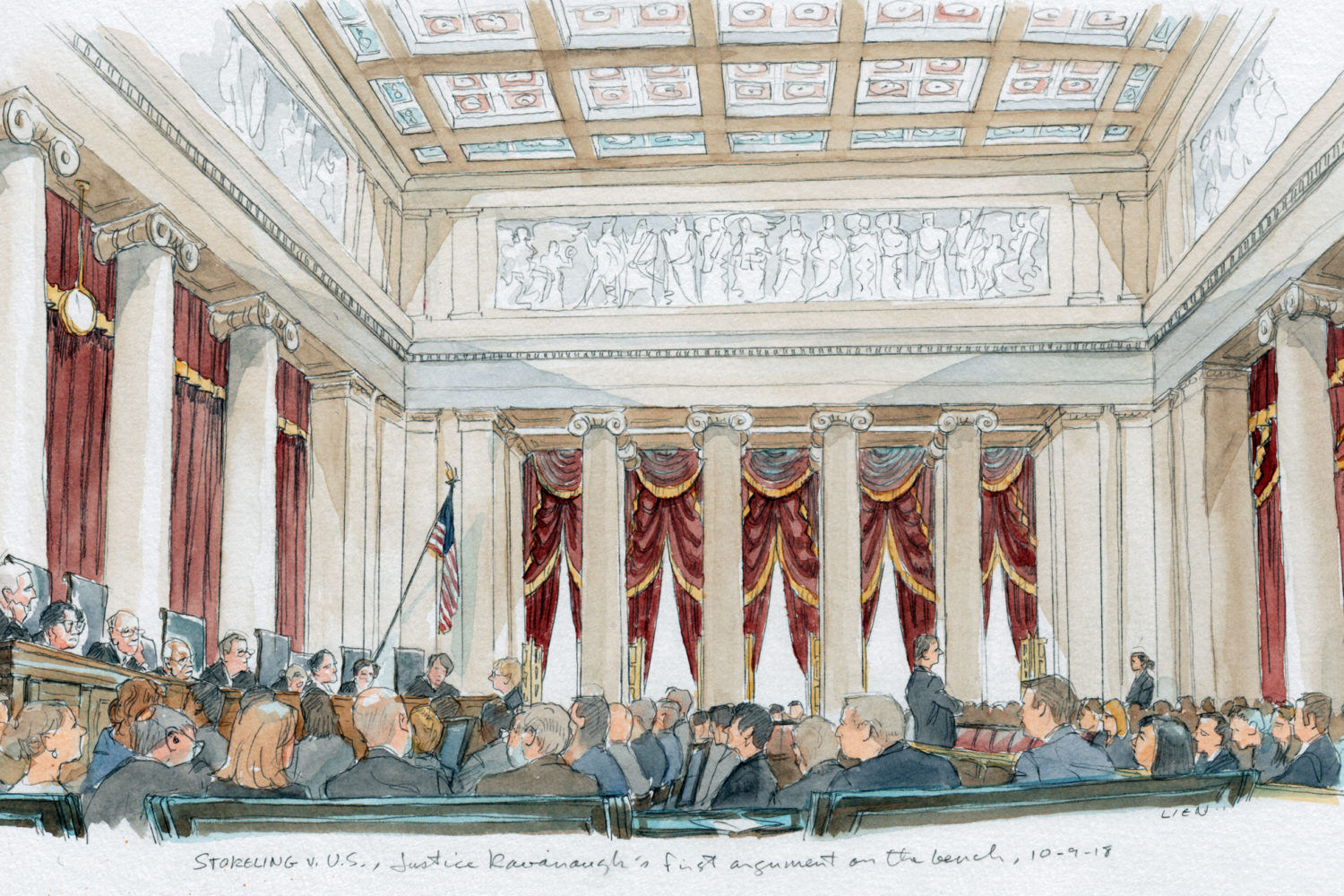

Of course, Washingtonians were never actually immune from lines. People have always camped out for concert tickets. The concept of the blockbuster museum exhibition—with the several-blocks-buster line—dates at least to 1976’s King Tut extravaganza at the National Gallery of Art. And it wouldn’t be a Star Wars movie premiere or a Harry Potter book launch without images of queued-up superfans sporting lightsabers or magic wands.

The difference today is that the fact of the lines is actively altering our experience of whatever can’t-miss thing we’re lining up for. Yayoi Kusama’s installation at the Hirshhorn, for instance, might ideally prompt visitors to think big thoughts—about, say, their reflected image of themselves or their puniness in the infinity of life. But as Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott noted, the real-world version is different. It’s harder to get to a contemplative place after an anxious half hour of making sure you’re lined up correctly, and harder still to do it in the minute or so you’re allotted before being moved along to the next room.

Likewise dining. Time was, hitting an exclusive restaurant for a birthday meal meant expecting to be pampered, or at least treated like any other customer spending several hundred dollars on a nonessential product. But there are few scenarios where spending a couple of hours shivering on the sidewalk outside Bad Saint is considered luxurious. That doesn’t change the fact that the meal you’re about to eat may be mind-blowing. It does, however, change the meaning of a mind-blowing meal. It’s about adventure, not comfort.

This status quo might once have made us resentful: Who are these jackasses forcing us to bide our time out on the asphalt like a Depression-era throng awaiting free apples?

Here’s the funny thing, though—we like it! In culinarily with-it Washington, bragging about the indignities visited upon us by destination eateries confers an odd sort of status. I’m so devoted to creative cuisine, the logic goes, that I’m willing to endure all manner of ill treatment from people who not so long ago would have been kissing my butt. Middlebrow slobs might settle for making a reservation and being welcomed warmly, but not true sophisticates.

***

Humans were using consumer behavior to show off long before Thorstein Veblen ever thought of the words “conspicuous consumption.” What’s changed over the years is just what sorts of consumption are seen as most prestigious. One generation’s luxury Cadillac is the next’s tacky gas guzzler.

Cultural products—a category that has come to include restaurant meals—are no different. There was a day when bookshelves and music libraries full of obscure, hard-to-find editions were a terrific way to show off. Check out my vinyl first pressing of the third Big Star album, the one the major label wouldn’t release. Can’t get that at Sam Goody. But now that just about any book or album is a couple of clicks away on Kindle or Spotify, the very notion of scarcity seems quaint, and the notion of showing off by displaying obscure content seems pointless.

So that leaves us with experiences, the thing marketers tell us millennials value so much more than possessions. And with lines, the thing that separates the lightweights from the cognoscenti. No wonder the Instagramming of food or gallery shows—for all the mockery—has become such a thing. Rather than just a cool picture, the images are trophies of having put in the time to get what someone else can’t, or won’t.

Human nature being what it is, it’s probably impossible to get us to stop looking for ways to outrank friends and neighbors. But we can always try to change the standards, perhaps to something a bit more tolerable for those with sore feet or tight schedules. So next time someone makes you wait in a preposterously long line, go ahead and whine about it. You’ll be doing us all a favor.

This article appears in the June 2017 issue of Washingtonian.