Growing up, most of us had the same deal with our parents. If we did our chores, were well behaved, and came home with good grades, they paid us an allowance. Conversely, if we didn’t do our duties around the house, got in trouble, or did poorly at school then we didn’t get our weekly payout.

Lori Atwood, a DC-based certified financial planner who has been advising families for nearly two decades, wants to upend that tradition. She believes allowances should be completely separate from discipline and duties.

“Don’t tie punishments to the loss of allowance,” she says. “If money is used as a yo-yo – I don’t like this or I don’t like that, so I’m going to cut your allowance – then that’s not going to help them form a healthy relationship with money.”

When it comes to helping around the house, Atwood says, “Chores make your child a decent human being. They need to recognize that they have to help out the community they are a part of, in this case, your family.”

Another reason is that the child may stop doing their work if they feel like they have enough money on hand or they take on a part-time job that provides them alternate income.

The true goal of the allowance is so a child learns how to manage their money and how to value purchases. “They need to ask themselves, ‘Was what I bought worth it,?’” says Atwood. “‘Was it not worth it? Most importantly, was it worth it in comparison to the other thing I had the option to buy?’ You want your child–not in a cruel way–to experience buyer’s remorse over something small, like sticker book, rather than over a Porsche when they’re in their 20s.”

There’s an overarching theme to Atwood’s approach. “You want to constantly reinforce the concept that you can’t have anything you want at anytime.”

Take that, entitlement!

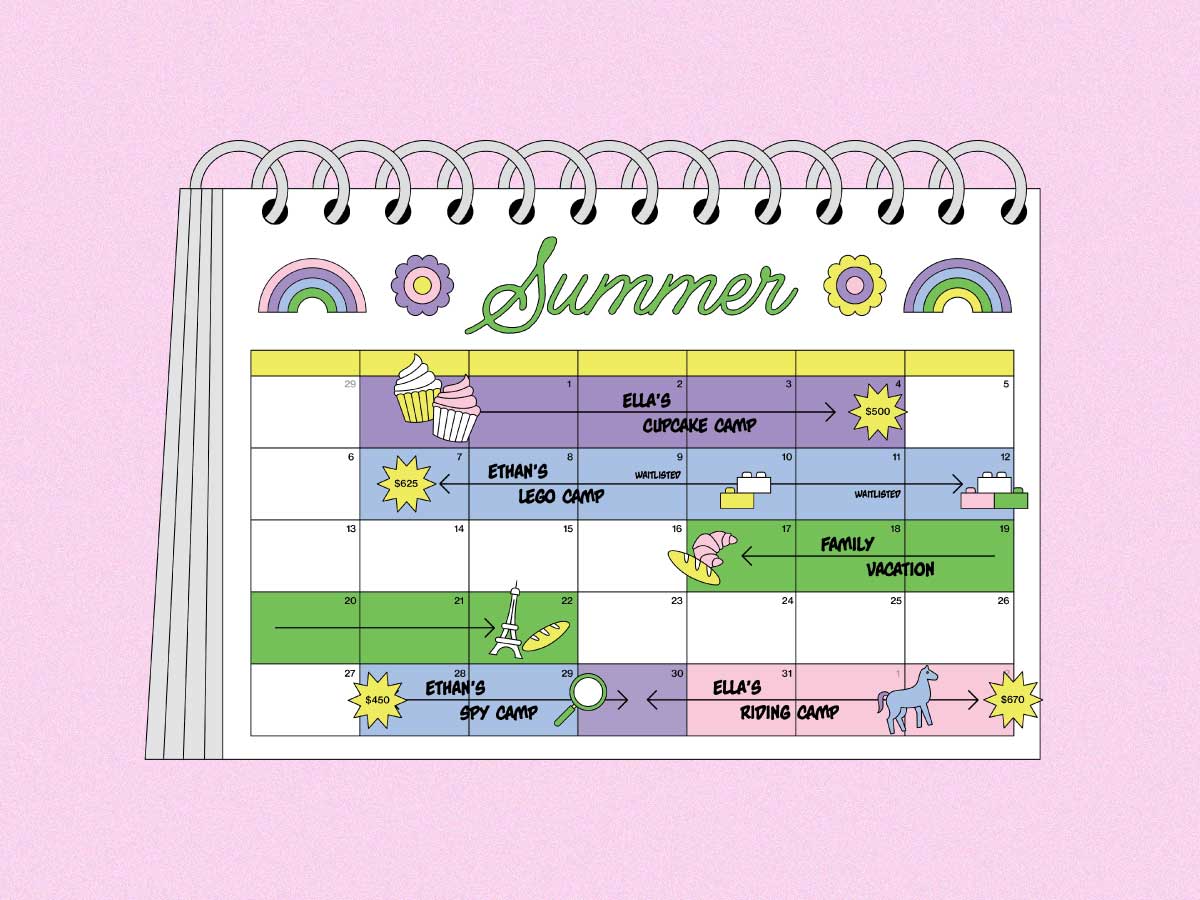

Parents should start giving an allowance as soon as the child is able to add and subtract, which is generally in first or second grade. Atwood suggests parents give one dollar a week for each year of age, so a 9-year-old would receive $9 a week. Since allowances are commonly given in cash, payouts should be made on a weekly basis, so the child isn’t carrying around a relatively large sum of money. However, as they child gets older, parents may opt to deposit the money into an account linked to either a pre-paid credit card or a debit card linked to a personal checking account, so the child can purchase items online or elsewhere.

Each week’s allowance should be divided into three compartments: spending, saving, and donating. “If they just see it as a pool of money to spend, they circumvent the decision-making where they choose between saving up for something larger or spending the money right now for instant gratification,” says Atwood. “Setting aside money for donation is a parenting choice, but I find that having a child be in service to others at an early age is not a bad thing.”

Though she recommends having conversations with your child about how they feel about the financial decisions they’ve made, she warns against making them too formal or forced. Keep them casual, so talking about money doesn’t become a stressful or emotionally fraught experience for the child.

When the child becomes a teenager and their needs get more expensive and more expansive, Atwood advises parents sit down with their child and tell them what they will cover. Anything beyond that comes out of the child’s allowance and any other money they might earn extraneously. “This conversation is the basis for your financial relationship with them in college,” she says. “They’re going to need spending money, but you don’t want to become an ATM. It’s not necessarily an easy conversation, but it will save you bundles of money in the long term.”

Most of all, it will help your child learn the importance of budgeting, a key skill that will benefit them for years to come.