Boaters who enjoy paddling their canoes and kayaks in the Potomac River about 26 miles upriver from Washington are facing a new hazard on the water: the closure of a 1.6-mile stretch of the river whenever President Trump visits his golf course in Sterling, Virginia. The closures, as specified in a regulation proposed by the US Coast Guard, would cut off access to leisure-seekers, campers, and whitewater kayak teams, imperiling numerous small businesses that operate along the shorelines, river enthusiasts say.

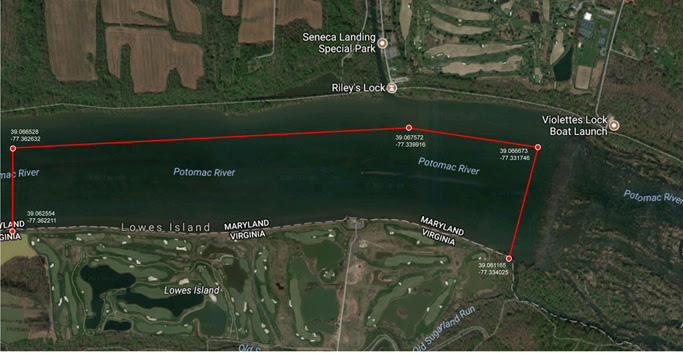

The Coast Guard’s regulation, which has been implemented on an interim basis, calls for closing the entire width of the Potomac in the designated security zone whenever Trump or other “high-ranking United States officials” are nearby. On the Virginia side, most of that span is covered by the Trump National Golf Club. But the Maryland side includes many boat launches and other vendors that service people looking to get on the water, like Calleva, an outfitter that runs large summer-camp programs. Under the Coast Guard’s rule, this would cut off entry points like Violette’s Lock and Riley’s Lock and make it impossible for boaters to reach points like Seneca Breaks, a popular whitewater spot used by competitive kayakers, including some who train for the US Olympic team.

The Potomac is about 2,000 feet wide in the Coast Guard’s designated security zone and is gentle enough above Seneca Breaks for hundreds of summer-campers to use on a daily basis. Even on Monday afternoon, about 300 people—including many kids—were out on the water, says Susan Sherrod, the chairman of the Canoe Cruisers Association, a boating club that’s pushing back against the new regulation. On a weekend, there could be more than 500 canoes and kayaks on the water, along with some motorized vessels.

For many boaters, the Coast Guard’s proposed method for announcing the river will close for the President is fairly useless. The interim rule reads that authorities will announce a closure over a marine-radio frequency, though most canoes and kayaks are not equipped with such devices, which are more often found on powerboats and larger sailboats.

“I own a sailboat,” Sherrod says. “I do have a marine radio, but no paddlers carry a marine radio.”

A Coast Guard spokesman says the agency is proposing a regulation about Potomac access because Trump has visited his course so often since taking office—12 times since March—that it makes more sense to have a permanent rule rather than a series of temporary measures. “We initiate the security zone at the request of the Secret Service,” Petty Officer 2nd Class Barry Bena says. “How they make the determination is up to them. We go ahead and enact the security zone.”

Calleva’s director, Matt Markoff, says he hasn’t lost any days of business yet, but a shore-to-shore closure could be deadly for his company, which launches from Riley’s Lock.

“They’ve turned us around and [we’ve] paddled away from the golf course,” he says. “If they were to close down the whole river, I’m in big, big trouble. I have camps that cross the river every day, through the security zone. I have to figure out what to do with 150 kids.”

Sometimes those campers are arriving from the Trump course itself, where parents drop off their kids who are picked up in one of Calleva’s war canoes and brought back after a day of paddling. Markoff is also no stranger to presidential protection.

“When Chelsea Clinton was a kid she came out to Calleva and both Obama girls came out,” he says. “I’ve dealt with the Secret Service. They’d come out and ask what are your plans for the day. That’s what I was hoping for.”

Before the rule was written, boaters who found themselves approaching the shores of Trump’s golf course weren’t kicked off the river entirely, though they sometimes got a brusque push away. Adam Van Grack, an attorney who’s helping Calleva and other riverside businesses navigate through the Coast Guard’s rule-making, says that on July 3, an armed man on a boat patrolling the Virginia shore asked him to paddle his canoe back toward Maryland but left him alone once he was more than 100 yards away.

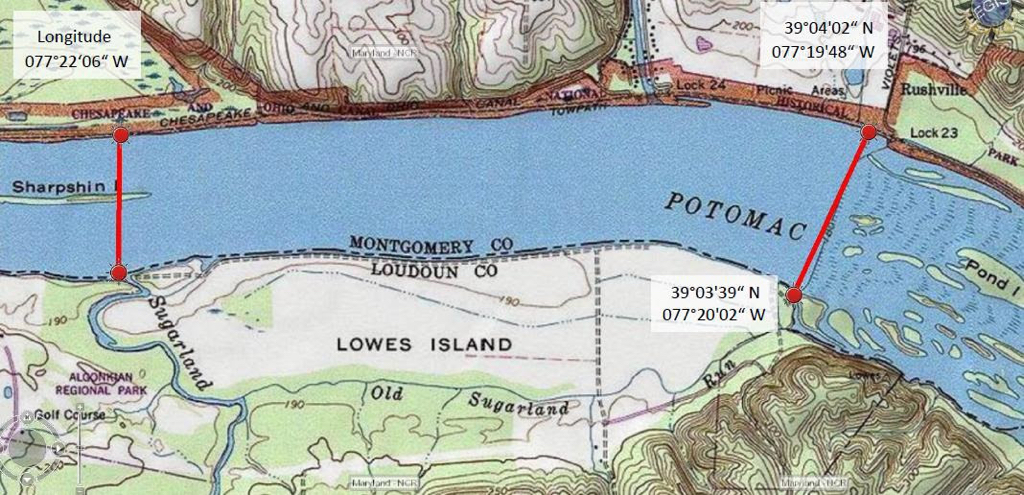

The Coast Guard’s regulation, while technically already in effect, is open to a public comment period, which Sherrod’s organization is using to suggest a less expansive boundary. The group’s proposed map would leave a wide buffer around the Trump golf course but leave the Maryland side open, along with a swath of the entire river below the golf course for access to Seneca Breaks and the old Patowmack Canal.

And even though he got turned away at gunpoint, Van Grack says the boating community would be better served by visual and verbal warnings on days Trump—or another VIP—is hitting the links than an indecipherable regulation. “What I’m saying is the way they’ve been doing it is the way they should do it,” he says. “Establish a boundary around the Virginia side. However, if they are insistent on having a larger boundary it needs to be significantly reduced to allow paddling in the river and access to the bypass canal and Seneca Breaks from Riley’s Lock.”

The boaters don’t take issue with the government’s need to guard Trump and other dignitaries. Their concern is that Trump’s visits could kill a popular recreation area and drain local seasonal businesses like Calleva.

“It’s perfectly fine for them to set up a security zone on the Virginia shore,” Sherrod says. “We know they have to protect the president, but closing off the entire river is extreme. Canoes, kayaks…these boats are too small and too wobbly to shoot a gun.”