To see the rest of our Explore the Shenandoah package, including panoramic hikes, cool caverns, and fun museums, click here.

Thomas Jefferson loved the Shenandoah Valley. As a young man, he crawled past stalagmites and mirrored pools in the Valley’s limestone caverns and spent many a night quaffing ales in Staunton. He described the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers near Harpers Ferry—the Valley’s northern boundary—and their passage through the Blue Ridge Mountains as “one of the most stupendous scenes in nature . . . worth a voyage across the Atlantic.” Jefferson considered Natural Bridge, the 215-foot-high stone arch near the Valley’s southern boundary, “the most sublime of nature’s works.”

Two hundred years after Jefferson’s day, the Shenandoah Valley remains one of America’s great places. Its grandeur derives neither wholly from nature nor from culture, but rather from harmony between the two. The wonders may be subtle, but they run deep and wide.

Like other valleys throughout history and myth, the Shenandoah has a promised-land vibe. Sheltered between the Allegheny Mountains to the west and the Blue Ridge to the east, the vast rolling plain—roughly 170 miles long by 25 miles wide—boasts abundant fresh water and some of the richest agricultural land in the eastern US. During 10,000 years of human occupation, the Valley, a natural travel corridor, has served Native American hunting and trading parties, Colonial-era farmers sending wheat to ports in Alexandria and Baltimore, dueling armies as they marched north and then south during the Civil War, and these days, Washingtonians seeking a quick escape from their workaday lives.

The Shenandoah Valley offers visitors many things to do. Explore the caverns, Natural Bridge, and other wonders that so enthralled Jefferson and another early tourist, George Washington. Wend your way along Skyline Drive and the Blue Ridge Park-way through Shenandoah National Park’s glowing canopy of autumn leaves—perhaps ditching the car to hike up to Humpback Rocks, one of many high outcroppings where billion-year-old boulders give you a hawk’s-eye view. Hop onto a bike—road or mountain—and see the Valley on two wheels, or paddle the oxbow bends of the eponymous river. Stroll through historic towns dripping with architectural charm. Dig into grass-fed beef, fresh eggs, and local wines as you restaurant-hop in this locavore’s paradise—or drop by farms and wineries to sample products directly. Along the way, Winchester’s Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Civil War battle sites, and Staunton’s Frontier Culture Museum—a collection of traditional rural homesites from England, Germany, Ireland, and West Africa showing the cultural forces that shaped the Valley—can help you make sense of the area’s rich history.

Here’s the magical thing, though: The Shenandoah Valley has, so far at least, avoided the Disneyfication that often afflicts charming heritage destinations. What makes the engine of authenticity tick is the people, whether they’re Valley-born and -bred, self-employed urban exiles looking for a fresh start, or first-generation immigrants raising produce. My family and I lived in Staunton (and on a nearby farm) for a dozen years, and generally speaking, we found everyone to be down to earth, resourceful, and cooperative; welcoming to outsiders; and possessing a reverence for history, the land, and life’s seasonal rhythms. In a word: stewards. Locals really care about the place, and it shows—in familiar exchanges at farmers markets; in the walkable, well-preserved historic towns; in the human scale of farms dotting the landscape.

Joel Salatin of Polyface Farm. Photograph by Greg Kahn.

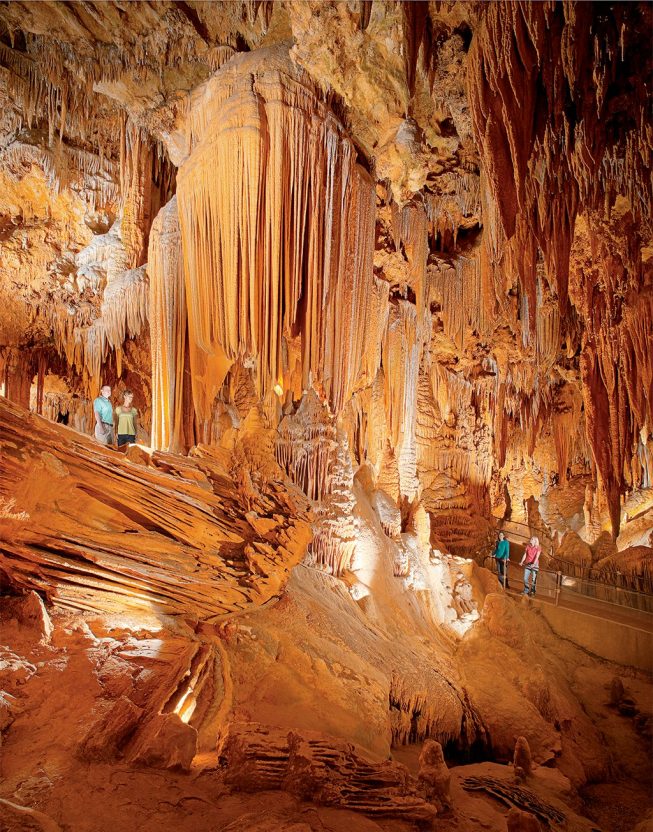

Joel Salatin of Polyface Farm. Photograph by Greg Kahn. Photograph of Luray Caverns courtesy of Moore Public Relations.

Photograph of Luray Caverns courtesy of Moore Public Relations. Photograph of historic Staunton by Woods Pierce.

Photograph of historic Staunton by Woods Pierce.Valley life is and always has been far from perfect. The Monacan, Susquehanna, Powhatan, and other Native American groups fought to control territory, only to be pushed out by hardscrabble Colonial pioneers in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the mid–19th century, the institution of slavery was deeply rooted in the Shenandoah Valley, though numbers varied by county. On the eve of the Civil War, 20 percent of Augusta County’s population was enslaved. Farther north (or down-valley) in Clarke County, more than 47 percent of the population was enslaved, while in nearby Shenandoah County, the percentage was around 5.

The Civil War trampled the Valley. As the so-called Breadbasket of the Confederacy and an important transportation corridor, it became a strategic theater in the War Between the States. General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign saved the Confederacy from early conquest. During Robert E. Lee’s 1863 march to Gettysburg, the Valley served as the general’s “avenue of invasion”—and route of return following his defeat. In 1864, in what became known as the Burning, General Philip Sheridan’s troops torched farms, fields, and gristmills.

After the war, the Valley began rebuilding. It had long been a tourist destination—the country’s first commercial show cave opened there in 1806—and by the 1920s, state leaders were pushing for a national park to show off the region’s beauty. Shenandoah National Park opened on December 26, 1935, during the depths of the Great Depression, showcasing nearly 200,000 acres draped along the spine of the Blue Ridge Mountains from Front Royal south to Waynesboro.

Over the years, the Shenandoah Valley has never strayed far from its small-farm, small-town roots. Agriculture still rules—the area is home to four of Virginia’s top five agricultural counties—but farmers are adapting, raising grass-fed livestock and organic produce and working hand in hand with talented chefs. And growing wine grapes. Jefferson, a devoted oenophile, would be thrilled that dozens of wineries have taken root. Breweries are popping up all over the place, too—a natural given the region’s grain-growing traditions.

I used to associate tradition with stagnation. That was one reason I left the South as a young man and moved to New York City. During my time in the Shenandoah Valley, however, I came to understand tradition as a way of connecting—to family and friends, to a place, to the past. Far from stagnant, the spirit of the Valley feels vital and whole. Spending time there—really getting to know the place and its people—is less a journey of nostalgia and more a reminder of what’s possible.

An interpretive plaque at the base of Natural Bridge describes the arch as “a miracle in stone, old as the dawn.” Human habitation doesn’t go back quite as far. Still, the Valley culture endures.

This article appears in the October 2017 issue of Washingtonian.