This summer, my family and I moved into a new house. We didn’t know much about it at first—just that it was built in 1914 by Washington developer Harry Wardman. This was no minor detail: Wardman was the leading builder during a local development golden age. For real-estate agents, a Wardman connection has become something to brag about when marketing a house.

But that pedigree didn’t mean a whole lot to me, I have to admit; I didn’t know much about the history of DC rowhouses. To learn more, I turned to Google. I soon found a site called Wardman’s Washington, run by Sally Berk, a former DC Preservation League president who is working on a book about Wardman. Her database confirmed that our house is a Wardman, and it also mentioned the architect whose name is on the building permit: Frank Russell White. White, it turns out, is a significant figure, having designed a slew of well-known buildings around town.

Then, while reading a blog post about White by local historian Paul K. Williams, I came across something surprising: White had gone to prison for making fake money. Wait, what? The guy who designed my house was a counterfeiter?

By now, I was hooked. Over the next few weeks, I did more research, digging into tax records, census info, newspaper clips, and other resources. The more I learned, the more the house’s history came alive around me; I began, in a sense, to see ghosts. Could Benjamin Mattingly, a newspaper reporter who lived here 100 years ago, have read his morning paper in the same spot I do? What about William Lusby, a retired superintendent of the Parker, Bridget & Co. department store who died in the house in 1943?

Mostly, though, I couldn’t stop wondering about the specter that was Frank Russell White.

White had no formal training, but he picked an auspicious era to launch a career as an architect. Born in Brooklyn in 1889, he moved to DC with his family when he was a kid. As a young adult, he seems to have gotten a job in the office of Albert Beers, then Wardman’s chief collaborator. When Beers died in 1911, Wardman tapped him for the lead role. Barely out of his teens, he found himself at the center of the city’s most prominent real-estate business.

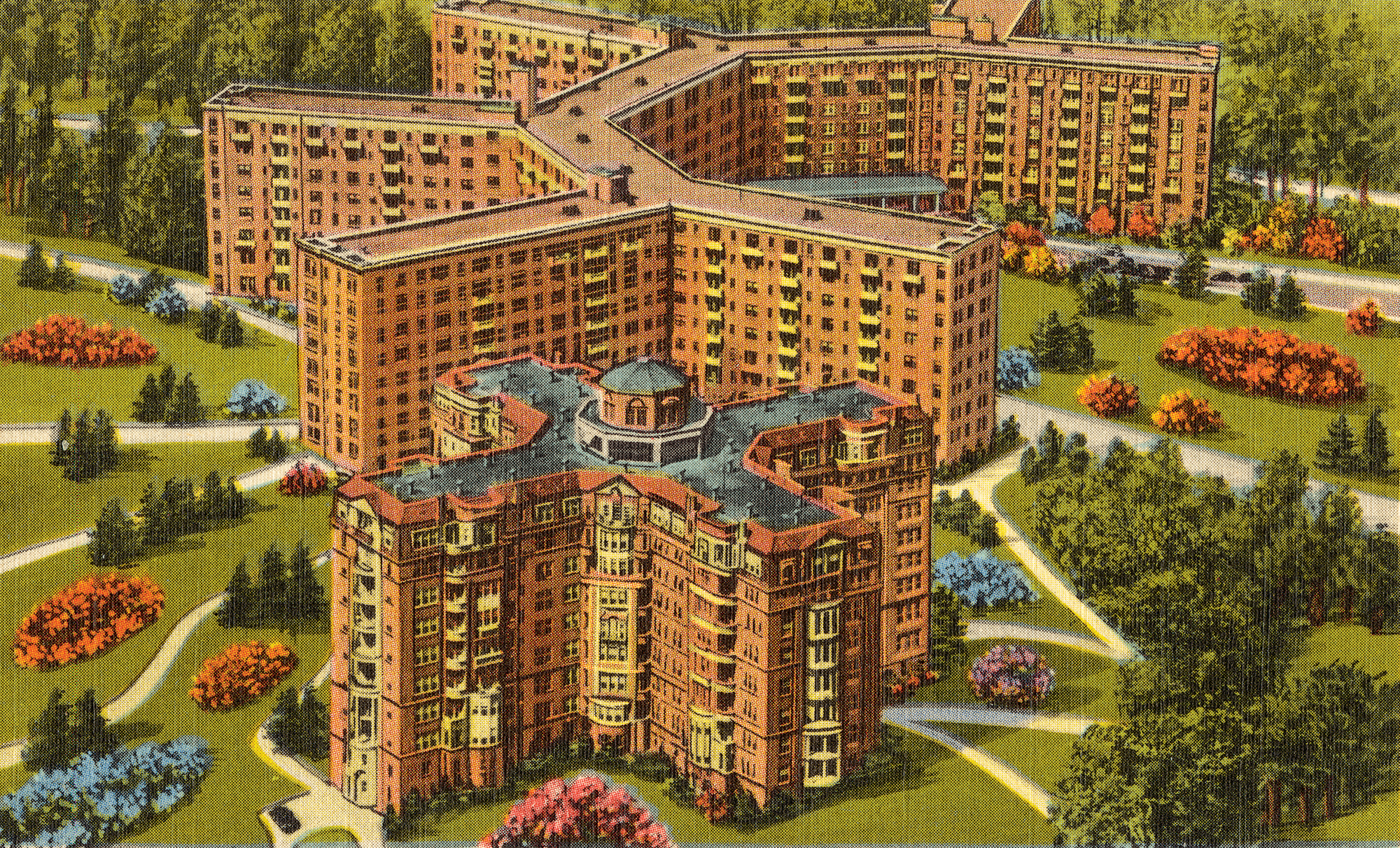

White’s Wardman buildings still dot the city: the Avondale near Dupont Circle; Somerset House and the Northbrook on 16th Street, Northwest; the Farnsboro on Florida Avenue, Northwest. His designs weren’t typically ornate or flashy. Instead, he favored a function-al but elegant style, often featuring simple brick facades and protruding cornices. White eventually started his own firm, and by the early ’20s, he had reportedly designed $40 million worth of Washington residences.

White’s most famous building was the Wardman Park Hotel, which opened in 1918 in Woodley Park. It was torn down in 1979—today the site is occupied by the Washington Marriott Wardman Park hotel—but in its time the luxury development was a phenomenon. It soon grew into one of DC’s most glamorous addresses.

White’s personal life, though, was falling apart. He’d married an aspiring actress named Eula Griffin when he was 18. Now in his thirties, White found himself in a tabloid marriage whose collapse was humiliatingly chronicled in the press. Eula sued for divorce in 1923, citing White’s “misconduct with several women,” as one newspaper story put it. White, meanwhile, told the court that Eula had taken up with a Navy lieutenant and was seen cavorting with him in the pool at White’s very own Wardman Park Hotel not long before they were both arrested for disorderly conduct. One story gleefully recounted White’s testimony that he had once walked in on Eula and “found her very lightly clad, the bedroom poorly lighted and a man sitting in the bedroom.” The judge ended up granting the divorce petition.

But lots of people survive rough relationships without turning into counterfeiters. What happened? I kept digging. It appears that things went really bad a few years after Eula had safely exited the story. In 1927, White took out a loan for $340,000 to develop the Parkway Apartments, a co-op building at Connecticut and Macomb, not far from the Wardman Park Hotel. It was an ambitious move for the architect, who was both designing and funding the project.

White was notoriously bad with money, according to an account from a relative that’s part of the White archive at the DC historical society, and seems to have blown a relative fortune on bad deals and “loans” to unscrupulous friends. If the Parkway proved to be a success, it could turn things around. If not, he’d be on the hook for the equivalent of about $5 million in today’s money.

The building’s 83 units went on sale later that year, with an ad in the Evening Star proudly announcing “F.R. White, Inc., Builder.” But the Parkway wasn’t the big hit he had hoped. Then the stock market crashed. By 1930—according to details recorded in that year’s census—he had given up his glamorous life in the city and was living with his mother near Bowie. The two were apparently unable to afford even coal to heat the house.

That’s when White found another use for his talents as a draftsman: fake currency. His method was ludicrously crude. White simply “raised” $1 bills to $100s, meaning he took real bills and changed the numbers in the corners.

A woman named Carolyn Wildman, who seems to have been his girlfriend, went to spend one of the bills at a Baltimore jewelry store. The clerk, no dummy, noticed George Washington’s familiar visage on the note and called the police. Wildman was arrested, and White surrendered to the Secret Service in October 1931. Bonnie and Clyde they were not.

White and Wildman both pleaded guilty. The judge sentenced White to two years in prison. Wildman got a year and a day.

After serving their time, the couple got married, and they stayed together the rest of White’s life. But his career never fully recovered. Though he continued to work as an architect, he mostly stuck to unglamorous jobs like gas stations and shops. He died in 1961 at age 72.

One recent morning, I spent some time at Wardman Court, a three-building complex in Columbia Heights built by Wardman and primarily designed by White. I was especially interested because White was likely working on the first phase around the same time he designed my house: The building permits were granted just two days apart, in March 1914. It’s also one of White’s best-regarded designs and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. And White actually lived there for a while with Eula and their young daughter. After doing so much research on White’s life, I couldn’t help but feel drawn to the place.

Like White, Wardman Court has had its struggles. Longtime Washingtonians know the building by a different name: Clifton Terrace. One of the most infamous symbols of DC’s bad years, it devolved into a drug-riddled crime magnet. For a while, it seemed like “the notorious” was actually part of Clifton Terrace’s name.

Wildman was arrested, and White surrendered to the Secret Service. Bonnie and Clyde they were not.

But in 1999 two developers bought it from HUD for $1, and since then they’ve entirely transformed the complex, offering comfortable low-income housing even as the surrounding neighborhood has radically gentrified. Today, residents enjoy a slew of services: a free food pantry, ESL and computer training, even vegan-cooking and Taekwondo classes.

When I stopped by, toddlers ran around a lush green lawn while their mothers chatted in Amharic (most residents these days are either Ethiopian immigrants or seniors who’ve lived there for decades). The only evidence of its grim past is a tall, we-mean-business iron fence that surrounds the grounds, with prominent signs warning against “illegal activity.”

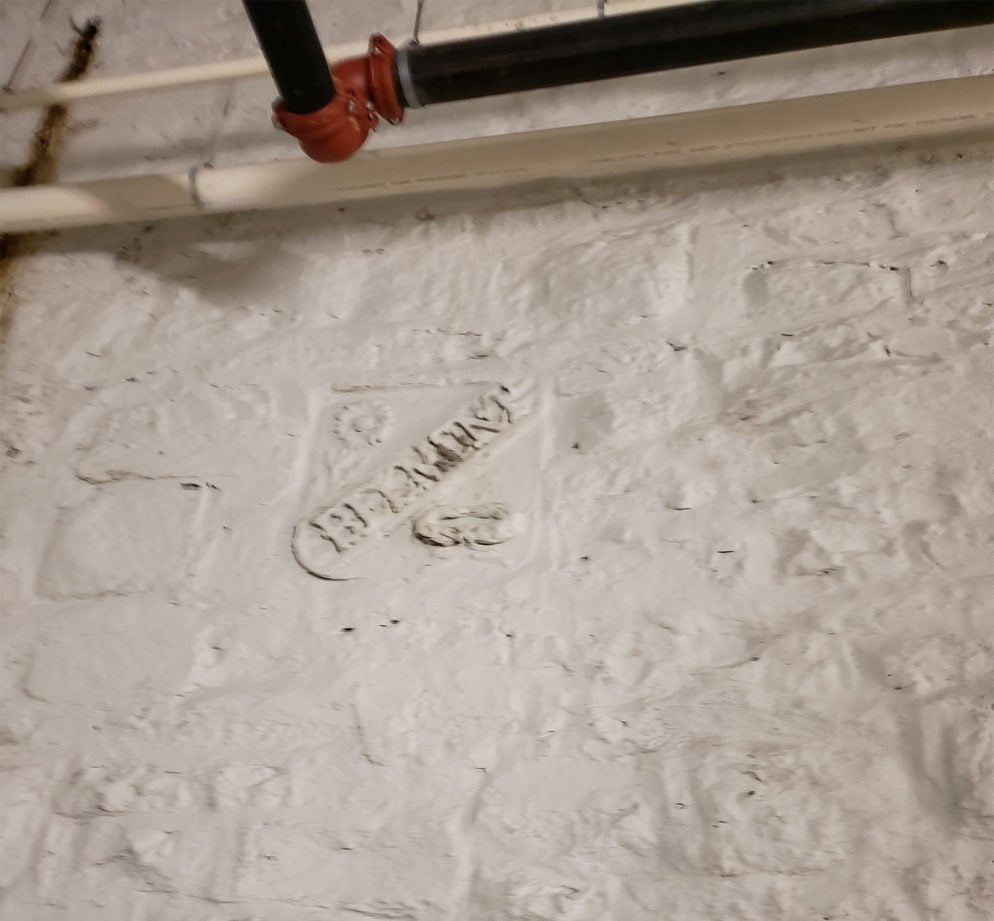

Inside, little remains of the original decor—just a set of marble steps. But the lobby is bright and pleasant, and a display in the corner shows off the original building permit and other documents. Still, I was hoping for more—some tangible link to the man I’d been hunting. At one point, I asked Channer Woolcock, the assistant manager who showed me around, if anyone had ever found anything old on the property. Actually, she told me, there was one thing. Woolcock led me down to the basement. “Up there,” she said. Set into the wall toward the top of the cavernous space was a single stone bearing a clear insignia. “Belmont,” it read in diagonally sloped letters. Neither of us had any idea what it meant, but it was cool and unusual, and it had to have been placed there by whoever built the building. But why? Another mystery.

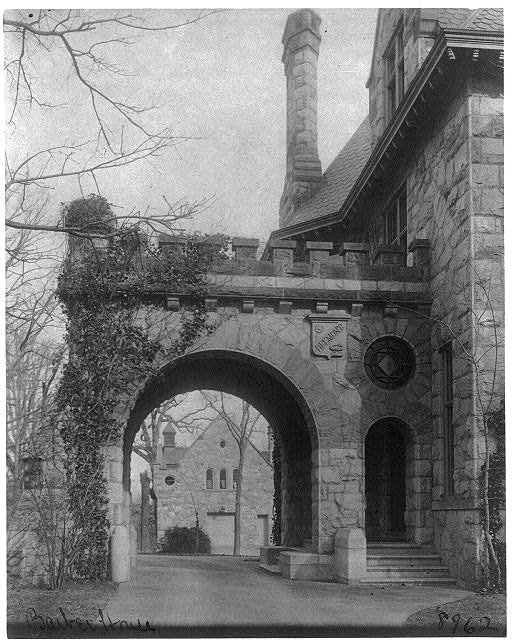

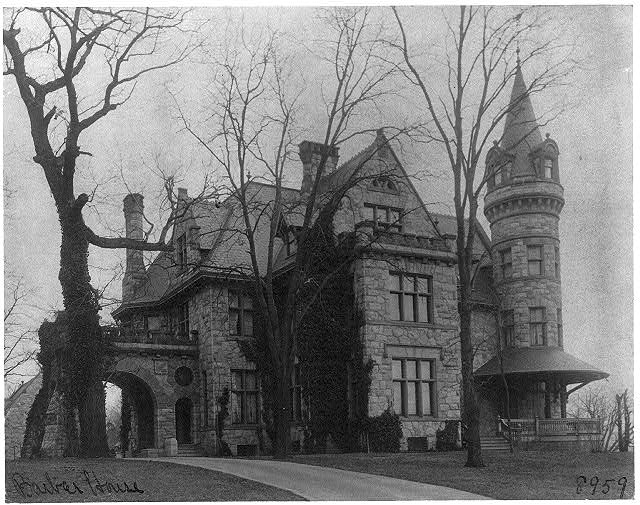

Later, while reading old newspaper stories about Wardman Court, I stumbled on the answer. Once upon a time, it was the site of a spectacular house owned by asphalt magnate Amzi Barber. The 1880s stone Queen Anne mansion was so grand that it had a name: Belmont.

Looking more closely at a photo, I spotted something over the driveway: a familiar-looking insignia. Could it be the one in the basement? A bit more searching revealed a close-up, and now it was unmistakable—clearly the very same engraved stone. Somebody had preserved this piece of the old house and incorporated it into the new building.

There’s no way to know who put it there, of course. But I like to think it was White. The ghostly message is as eerie as it is clear: “We were here.”

Photograph by Rob Brunner.

Photograph by Rob Brunner. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.

Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.

Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.Top left: The Belmont insignia as it looks today in the basement of Wardman Court. Top right and bottom: What appears to be the same stone as it looked in the old Belmont house.

As it turned out, our new house also had a secret in the basement. Not long ago, an electrician found a pair of eight-inch wooden spools of blue and purple thread tucked way back in the ceiling, where they’d obviously been forgotten for many decades. By now, I was well enough versed in the house’s history to have a possible suspect. Perhaps they were left there by Mary Hendricks, a widow who lived in the house in the ’20s and ’30s. The spools were a vivid reminder that the ghosts I’d been chasing were real people, and this house was their private world. Even though Hendricks died in 1938, it still felt like we were intruding.

That odd sensation of collapsed time has faded since we’ve started to settle in. I’m still fascinated by our house’s past—and by White, whose presence I now sense every time I drive by one of his buildings around town. But it’s our home now, and as our routine has begun to fill the spaces that were once so unfamiliar, we no longer feel like trespassers in somebody else’s story. We’re becoming part of the house’s history ourselves, adding our lives to the ones that came before us, ghosts in the making.

This article appeared in the August 2018 issue of Washingtonian.