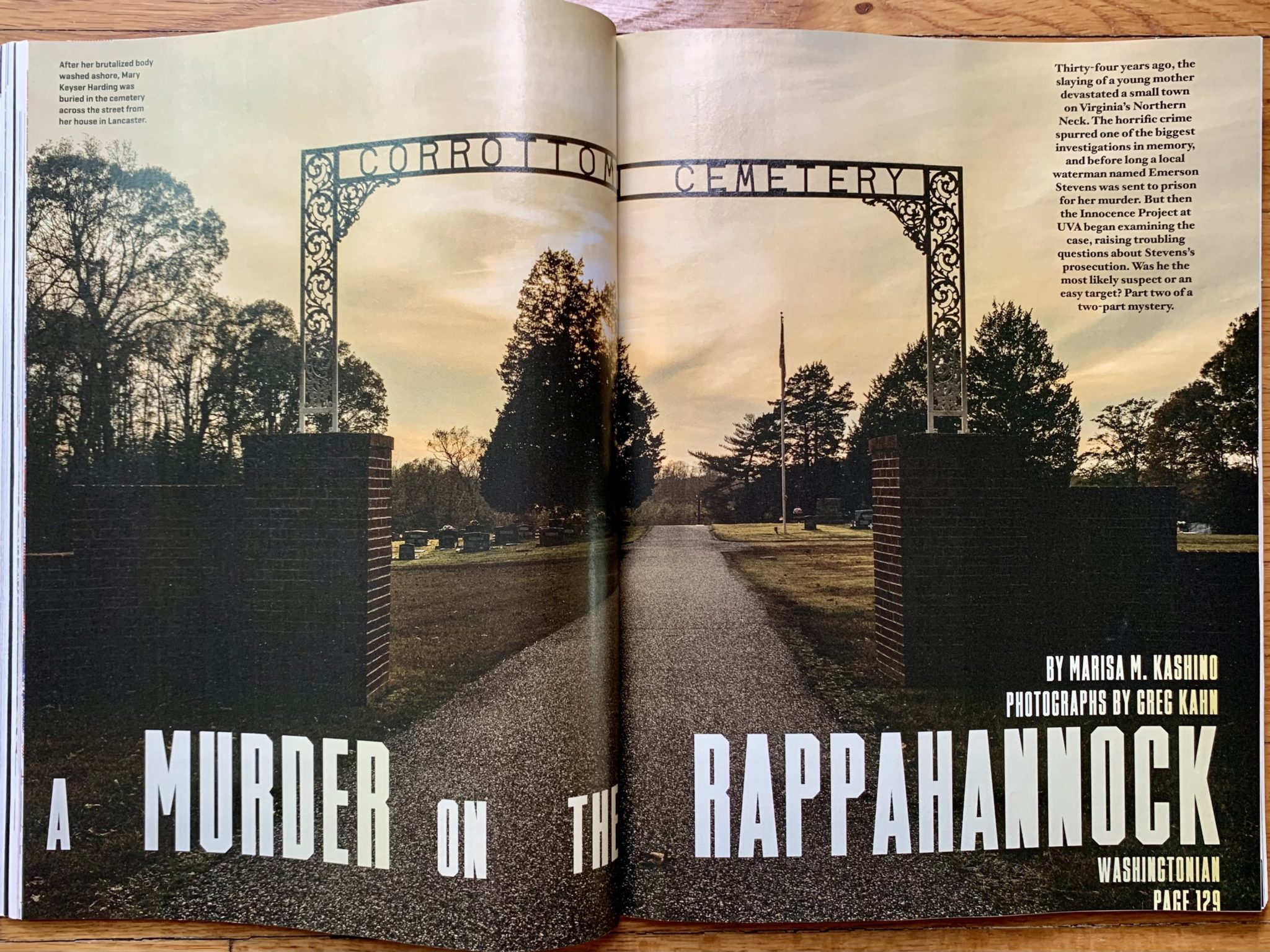

Emerson Stevens, the man at the center of a two-part Washingtonian investigative story from 2019, was granted an absolute pardon on Monday by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam. Stevens was convicted in 1986 of murdering Mary Keyser Harding, a 24-year-old mother of two, in a small fishing town on Virginia’s Northern Neck. The Innocence Project at the University of Virginia had been working to exonerate him since 2009.

When he was convicted 35 years ago, Stevens was a fisherman with a ninth-grade education and no history of violence, who knew Harding only in passing. He has always denied any involvement in the crime. When Washingtonian published its story about the case, Innocence Project lawyers Deirdre Enright and Jennifer Givens had recently tried and failed to get Stevens exonerated in state court. In 2020, they filed a new petition challenging his conviction in federal court.

Those efforts can now come to an end. In his order Monday, Northam wrote: “Upon careful deliberation and review of all the information and circumstances of the matter, I have decided it is just and appropriate to grant this absolute pardon that reflects Mr. Stevens’ innocence of Abduction with Intent to Defile and First-Degree Murder, for which he was convicted on July 12, 1986.”

Stevens, who was paroled in 2017, after the Innocence Project and a slew of other supporters advocated for his release, now lives not far from Lancaster, the town where he grew up and where Harding was murdered. He currently works as a house painter. Though he was out of prison when I met him back in 2018, he had to abide by strict parole conditions, and more important, he wanted badly to clear his name. “I know I’m innocent of the crime, and I don’t want that on me,” he said.

Reached over the weekend, after he and his lawyers got the early word that the governor would pardon him, Stevens told me the news still didn’t quite feel real. He said he was celebrating with Pizza Hut and Pepsi.

The only physical evidence in the case against him had been a strand of hair, and the state had used a now-debunked forensic technique to link it to the crime. The Innocence Project lawyers also argued that the lead investigator assigned to Harding’s murder, Virginia State Police detective David Riley, had coerced witnesses and neglected to investigate other viable suspects. They asserted that the prosecution withheld evidence of Stevens’s innocence and knowingly presented false testimony. Indeed, the state’s star witness—the only person who said he’d seen Stevens’s truck at the crime scene—later pled guilty to obstruction of justice for lying on the stand.

During the year that I spent reporting on the case, I also met Lancaster locals who said Detective Riley had tried to bully them into lying. But the most troubling revelation came when Riley, long retired from police work, agreed to sit down for a lengthy interview. A key piece of the case against Stevens had been his admission that he’d stopped to pee on the side of the road near Harding’s house, on the night she was abducted and killed. It was the closest Stevens ever came to placing himself at the crime scene. During our conversation, Riley offered a new, stunning detail: He said it had been him—Riley—who’d crafted the story about Stevens stopping to pee, that he had fed it to Stevens during an interrogation, and that Stevens had simply regurgitated it. “I said, ‘You probably had to relieve yourself’—I didn’t use those words, because men don’t use those words—but I said, ‘You probably stopped to relieve yourself on the side of the road,’” Riley told me.

Of his interrogation strategy, Riley explained: “If you can’t get a direct confession, you just try to get them to talk. They’ll say things against their own interest as a way to wiggle out. The whole thing is to keep people talking and steer them in the direction you want them to go.” The Innocence Project wound up using this reporting in their federal-court petition to clear Stevens.

Though Stevens has now gotten justice, Mary Keyser Harding, of course, has not. At the time of her death, she was a bookkeeper at the local bank and a devoted mother to her four-year-old son and one-year-old daughter. Many of her family and friends shared heartwarming memories of her for my 2019 story, including this one from her high-school best friend, Marjorie Holt:

“She had a spark—a spirit. She just was one of those people who could talk to anybody,” Holt says. “I was shy and kind of bullied. She definitely saved me in high school.” Before graduation, Mary gave her a gift. Feeling the weight of it, Holt was embarrassed, thinking there was no way Mary could afford whatever was in the box. It turned out Mary had cleaned up some old bricks from her yard. “She says, ‘These are four bricks to help you build the rest of your life.’ ” Holt chokes up. “She was a deep soul.”

You can read the complete two-part story here.