Starting in May, shoppers at the Springfield Town Center can stride through the golden arcs of McDowell’s and order a Big Mick—a burger that is totally different from that other sandwich, thank you very much, because the buns don’t have seeds.

McDowell’s is the restaurant at the heart of the 1988 film Coming to America, the McDonald’s knockoff where Eddie Murphy’s character mops floors until he wins the heart of the owner’s daughter. The McDowell’s in Springfield—a “pop-up parody restaurant fan experience”—is crafted to be as screen-accurate as possible, down to the striped wallpaper by the order counter.

McDowell’s will occupy a storefront near the site of last year’s Moe’s Tavern pop-up, and the same man is behind both: Philadelphia-based Joe McCullough, a Star Wars enthusiast with a background in costume fabrication and home construction. His company, JMC Pop Ups, transforms vacant mall storefronts across the mid-Atlantic into immersive pop-culture experiences. Think Galaxy Burger: a sci-fi burger joint with an interactive Millenium Falcon cockpit.

“Our experiences are a little different,” McCullough says of his niche in the pop-cultural pop-up world. While many other pop-ups are centered around a selfie wall or branded drinks, McCullough is obsessed with creating immersive scenes of lifelike accuracy. “We try to make it like you’re really there,” he says.

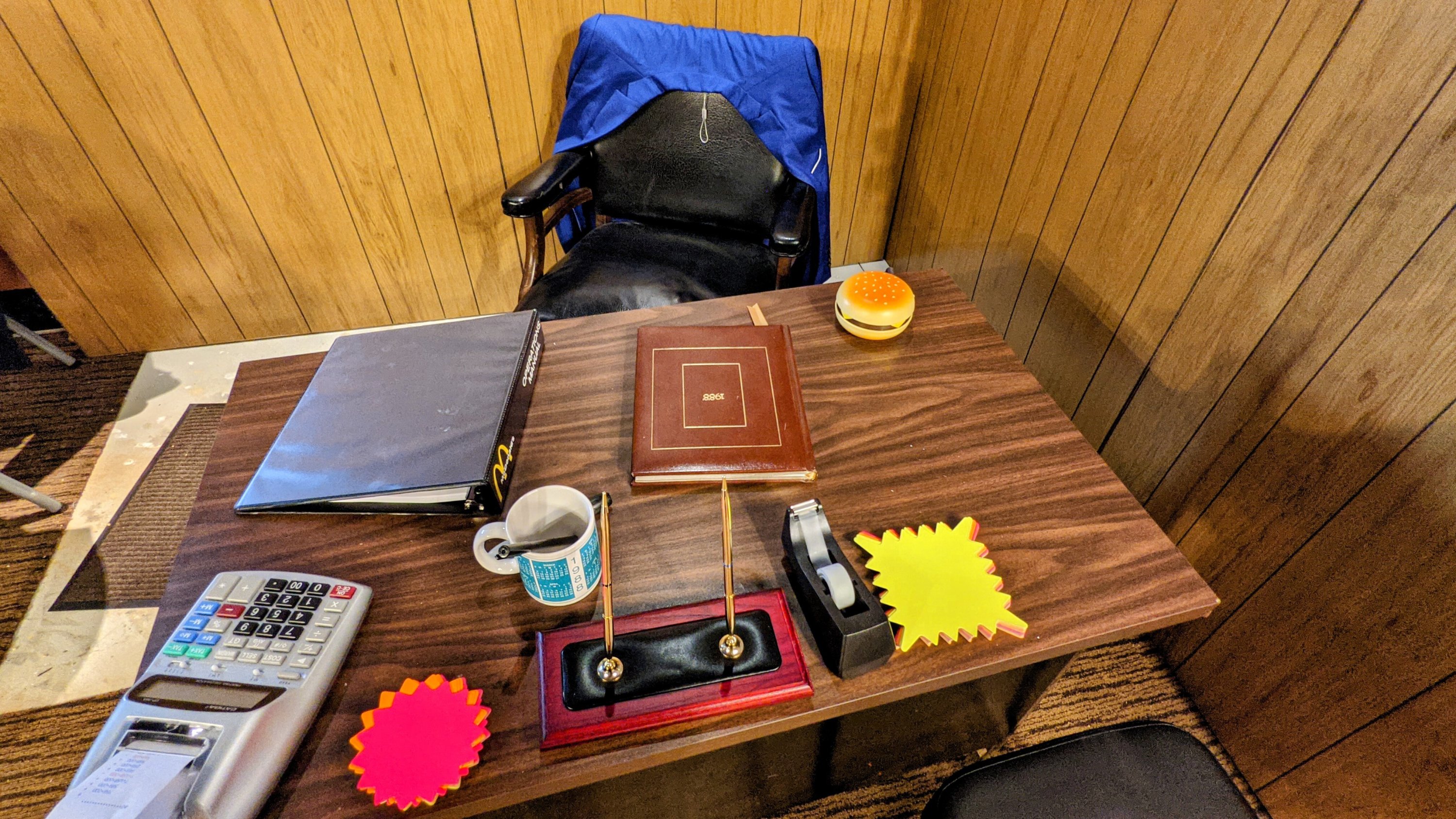

In that spirit, McDowell’s will be a multi-room installation that includes not simply the restaurant’s order counter (which serves actual Big Micks), but also re-creations of the dingy apartment where Prince Akeem lives, and Mr. McDowell’s office (guests can sit at his desk, don his blue blazer, and pick up the cheeseburger phone).

Of course, selling tickets to a meticulous re-creation of a Hollywood blockbuster is the kind of thing that might make some suits in LA a bit itchy. But ironically, the intellectual property conundrum is another tie-in to the film.

In Coming to America, the owner of McDowell’s implies that he has a trademark issue. “Look, me and the McDonald’s people, we’ve got this little misunderstanding,” he explains. “They’re McDonald’s. I’m McDowell’s. They’ve got the golden arches. Mine is the golden arcs.” In that scene, a photographer—presumably from McDonald’s—furiously photographs those golden arcs before sprinting down Queens Boulevard, perhaps in the direction of the courthouse.

[su_youtube url=“https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXgx7Uzislo&t”]

When I ask McCullough if he, too, has a trademark problem, he chuckles. “I’m not a lawyer, but I have lawyers,” he replies. “I guess I don’t want to get into legal and end up in trouble in your article.”

But throughout our conversation, he stridently foregrounds the phrase “fan-made parody.” It’s conspicuous legalese: buzzwords meant to short-circuit copyright claims by invoking the doctrine of fair use. The pop-up isn’t affiliated with the movie studios that made Coming to America, and McCullough hasn’t touched base with McDonald’s corporate—unlike the producers of Coming to America, who apparently did clear their McDowell’s plotline with McDonald’s HQ.

But McCullough always alerts local McDonald’s franchises before wheeling a McDowell’s into town. And in general, he says, they’re chuffed—some want to do cross promotions, while others simply come for lunch. “Trust me,” he says. “I’ve worked for McDonald’s before. The McDowell’s popup is no threat to them, it’s free marketing.”

More nettlesome might be the entertainment business. Back in 2018, a day-old Rick and Morty themed pop-up in Shaw was forced to shutter after receiving a cease-and-desist from Turner Broadcasting, which owns the show’s intellectual property. McCullough knows about this—due to fan requests, he himself looked into doing a Rick and Morty–themed pop-up, saw what happened in DC, and backed off.

So it’s perhaps out of legal caution that McCullough draws an odd distinction between McDowell’s and Coming to America. “We don’t touch Coming to America,” he claims. “We more focus on the McDowell’s aspect. You know, the parody of McDonald’s.”

But what about the meticulous replication—the cheeseburger phone and Mr. McDowell’s blazer? He ventures that a jacket and a novelty landline are simply “common off-the-shelf things that are in the world,” distinct from the film’s actual IP, which he’s cautious about. For instance, McCullough created a throne backdrop for the popup. “It’s got the purple carpet, the purple throne. But we don’t have the Zamundan crest behind the chair.” A purple throne is generic—Zamunda is Coming to America.

To any lurking studio execs smelling blood in the water, a caution: the Rick and Morty people came off as killjoys, and taking down McCullough might be worse. He can’t be accused of profiting from Coming to America, since the proceeds go to charity. McCullough initially launched his pop-up business to keep his his youth-centered robotics nonprofit alive amid pandemic losses, and proceeds from the Springfield McDowell’s will benefit the DC chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers.

Besides, imagine explaining this in court: the Springfield McDowell’s is an unauthorized imitation of a fictional restaurant, which is itself an authorized imitation of McDonald’s that nonetheless plays at trademark infringement for laughs. If you can’t follow that, I doubt the judge can either. I recommend a Big Mick and a nap.

Correction: This article originally said the McDowell’s pop-up would occupy the same Springfield Mall storefront as a Moe’s Tavern pop-up did. It will not.