Last week, while flying out of BWI, I passed a bar selling crabcakes. For a moment, I contemplated stopping—but good sense grabbed me by the throat: Ordering an airport crabcake before hopping on a six-hour flight seemed like a death sentence. Instead, I ate a breakfast sandwich from Dunkin, swallowed half a Klonopin, and drank a glass of wine on the plane.

When I returned home, I learned something wild: For the first time ever, DC’s Restaurant Week now includes airports. This week, at both Dulles and National, a handful of places are participating—among them are Chef Geoff’s, El Centro, and Reservoir. How marvelous, I thought. How bizarre! But then I had to ask: Is the airport an appropriate venue for a three-course prix-fixe meal? And what about crabcakes? Is it ever okay to order one before a flight?

There was only one way to find out.

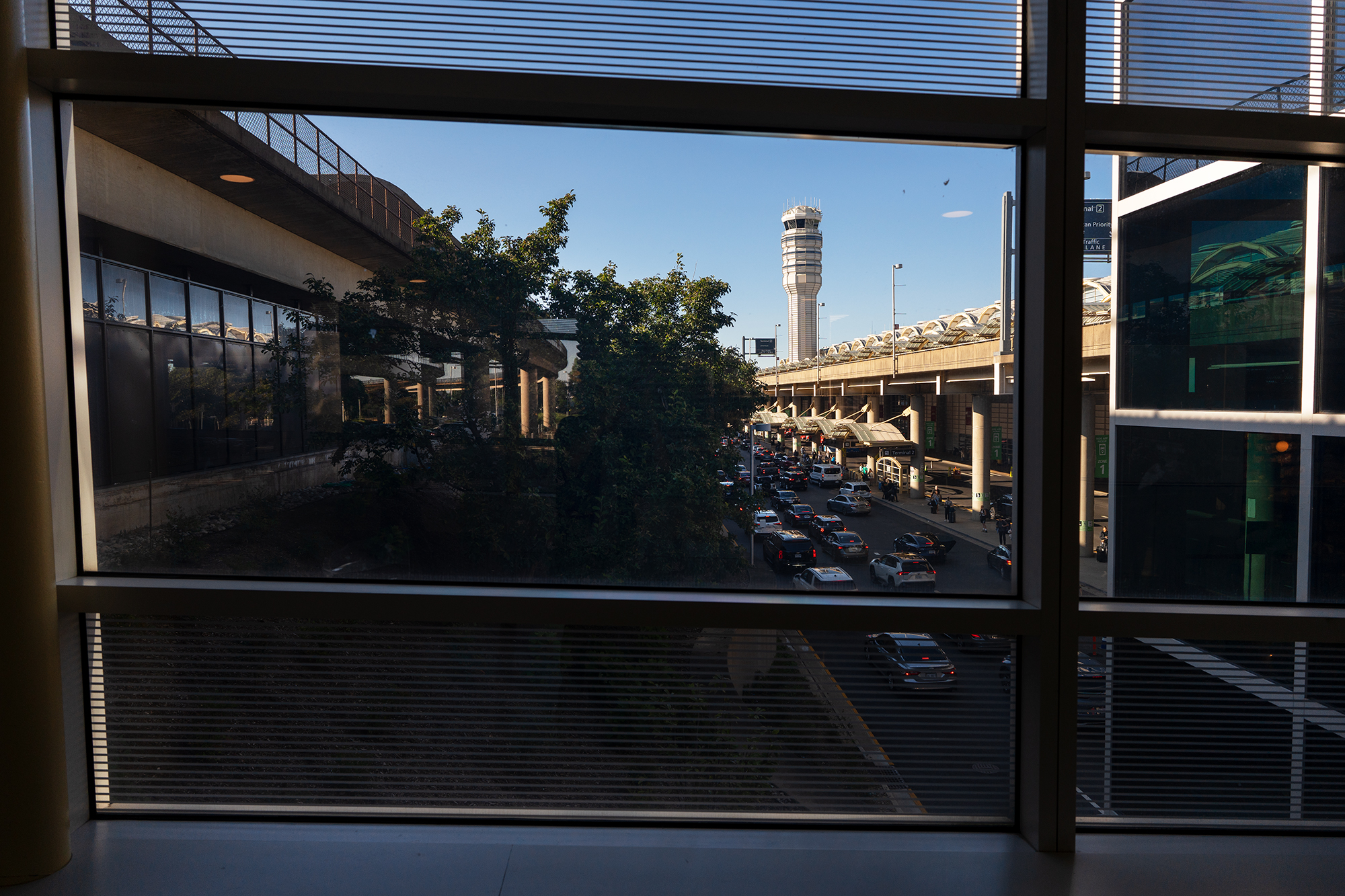

Through an airport publicist, I arrange a 5:30 PM reservation at the Legal Sea Foods at National—and the reservation turns out to be clutch. When my husband and I arrive, the place is packed. Wine glasses are sweating, and suitcases are tucked under unused chairs. The host ushers us to a corner table just across from “America!” and the Spanx boutique.

The ambiance is striking. Golden sunlight drips from the vaulted ceiling and slices through the windows by the gates. With awe, my husband describes the architecture of Terminal B as similar to “the internal armature of a Fabergé egg.” Feeling daring, I order some oysters. My husband eyes me with alarm.

Sidney Woods, a member of the airport’s marketing team, has already addressed the elephant in the room. While escorting us through security, he admits that “There’s still a perception that airport dining is not on par with the street.” Restaurant Week, he feels, is an opportunity to “showcase the airport culinary scene” and make it as respected as anywhere else. Still, when the first course arrives—oysters, clam chowder, and caesar salad—I’m a little afraid.

I don’t need to be. From the first bite of chowder, I’m smitten. It’s gooey and rich, with chewy clam bits and tender potatoes. Delicious. Perfectly thick. The server says the oysters are half from Wellfleet, half from somewhere I didn’t catch. The Wellfleet oyster is fine, briny and tart, but the other one pops. It’s voluptuous and buttery, a little tang from the mignonette. Airport oysters! Who knew! So far, things are going well.

In advance of our reservation, I’d texted some friends for their thoughts. One deemed airport fish “too volatile” to order. Another said she’d only get it in Japan. In a group text, a consensus emerged: Ordering a Filet-O-Fish seems fine, given that fast food is similar everywhere. But a high-end, sit-down airport salmon? Everyone said hard pass.

Nonetheless, a salmon appears before me—peach-colored with a bronzed sear, laid atop a smear of tzatziki with a couscous salad on the side. It’s just okay. The quality of the fish seems fine, but the flavor isn’t much. It needs salt, pepper, and lemon—which, to be fair, the restaurant provides. The best parts of the salmon are the skin (crispy as a chip) and two citrusy cooked tomato slices on top. I don’t love this course, but it beats group-text expectations by not inducing gastrointestinal distress.

The crabcake sandwich, on the other hand, is a star. It’s served with tomatoes, avocado, and aioli, all heaped inside a hamburger bun. It needs no additional seasoning. The sauce has a little kick. The fries, also, are excellent—pillowy and warm, a good snap on the edges. They don’t wilt when held aloft. When the server appears, there’s still salmon left, but the crabcake plate is clean.

Then comes dessert, which is not some tiny, bite-and-a-half, fine-dining gimmick. These pie slices are honkers—one is key lime, and the other is Boston cream, which must be at least three inches tall. Both are good; the key lime is beautifully tart, and the Boston cream is spongy and soft, topped with a crumbled cookie grit.

When we finish, I am so aggressively full that I sit, catatonic, eavesdropping on the next table over. It’s occupied by men in nice watches using words like “artillery,” “intel,” “Jeff Sessions,” and “ground war.” “Ain’t nothin’ wrong with seven in the morning drinking,” one man says. “We all went to mass together,” he adds.

While digesting, my husband raises an important question: Could we get on a flight after this meal? The issue isn’t what we expected—neither of us feels any instability of the gut. It’s just that the food was so hearty. My stomach strains at my jeans. Could I, right now, contort myself into a middle seat and then hold still for several hours? I guess, but I wouldn’t prefer it. On the other hand, before I need to eat again, I could probably make it to Taiwan.

To exit the terminal, my husband and I—who are not ticketed passengers—require an escort. Amanda Herman, the Legal Sea Foods manager, walks us to the doors. As she does, she serves the fourth course, which was not an advertised component of Restaurant Week; it’s gossip, and it’s piping hot.

Before the fall of 2021, the airport Legal Sea Foods was located outside of security, which created some conflicts over chowder. This chowder—for understandable reasons—is a cult hit among airport patrons, and people would apparently try to take it to-go. But you couldn’t take the chowder to-go—it’s a liquid, and TSA would seize it. So one man developed a workaround.

Every three-or-so months, Herman says, he would come to National with an empty suitcase, which her staff would fill with ice. After purchasing three gallons of chowder, he would place them in the suitcase, check the bag, run through security, then hop on his flight. “He had the timing down perfect,” she says.

Among the chowder’s fans, Herman adds, is John Kerry, who used to regularly fly through National. Apparently, he’d stand at the Legal Sea Foods bar and eat a chowder, then take one to-go on the plane. Wait, I protest, I thought you couldn’t take it to go? Well, you can’t—unless you’re the Secretary of State.

My husband and I don’t begrudge the Secretary this indulgence; we agree that the chowder is that good. But in evaluating our dining experience, we’re both a little bewildered. Had I gone to a freestanding, non-airport restaurant and paid $55 for a three course meal featuring that salmon, I’d be bummed. But the crabcake? I’d eat it anywhere. Ditto, the pie.

Yes, Sidney Woods insists that the “airport culinary scene” is just as good as the street, but it feels only fair to grade on a curve. For the airport, this was excellent—a real delight of a meal. Next time I fly out of National, I’ll gratefully skip the Dunkin. And after washing a Klonopin down with some chowder, I’m sure I’ll feel great on the flight.