Contents

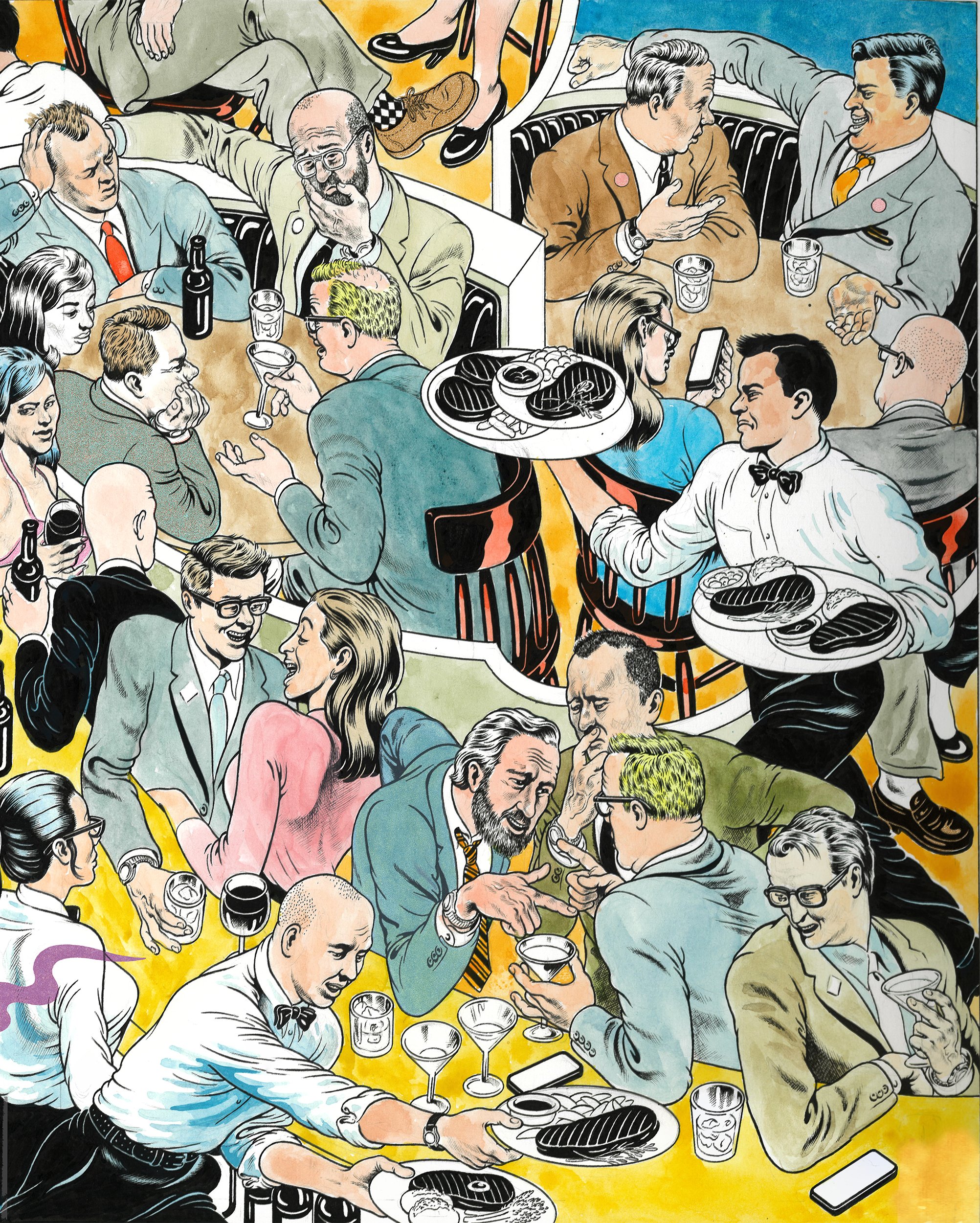

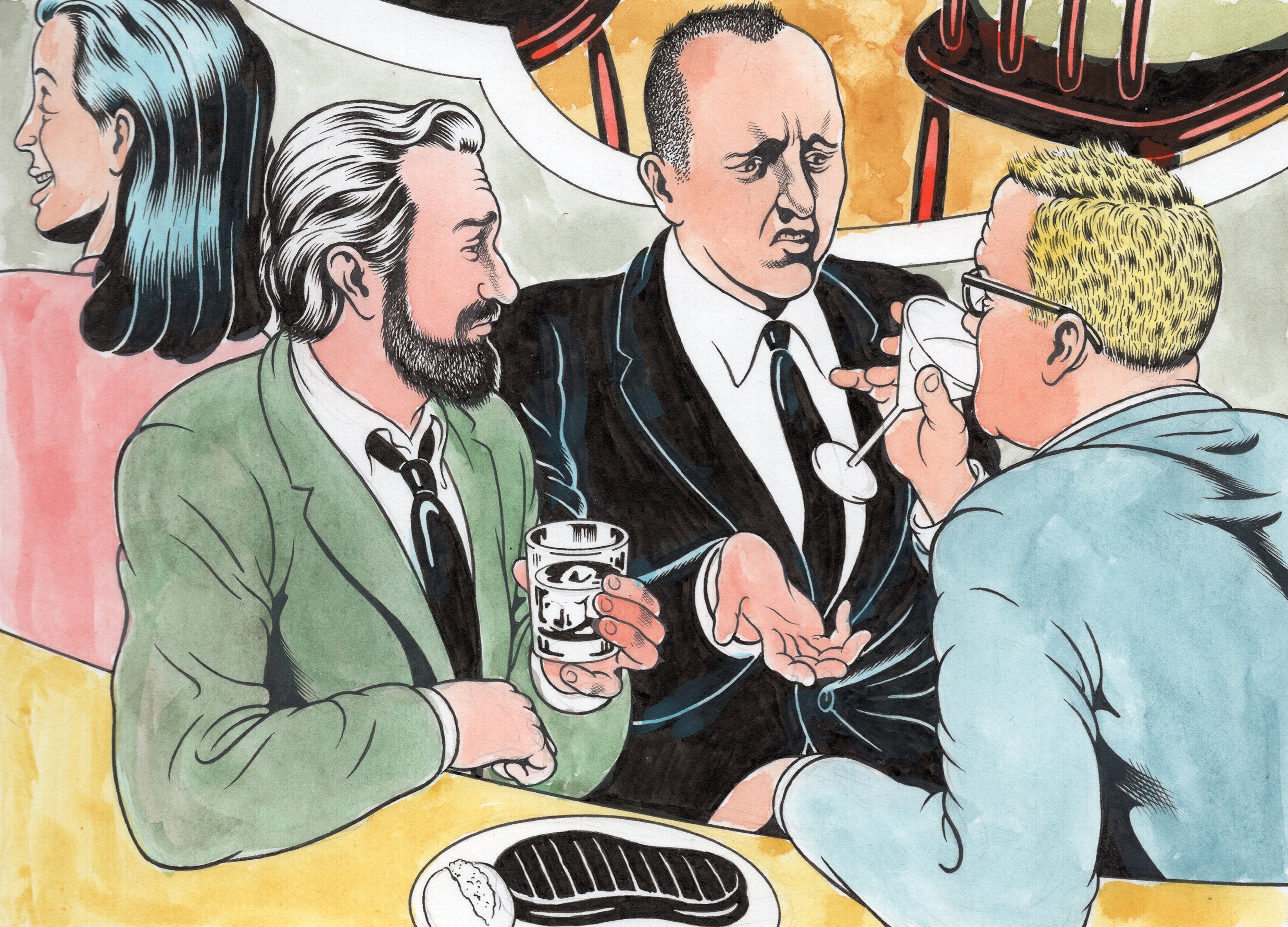

Beneath a giant buffalo bust, Republican lobbyist Mark Smith sips a three-olive Belvedere martini at the bar of DC’s Capital Grille, ready for his own kind of hunt. Congress is in session this Wednesday in July—just before the assassination attempt on Donald Trump and the abrupt exit of Joe Biden from the presidential race—and the place is packed.

Smith shakes hands with a former Trump Labor Department official. He congratulates Congressman Greg Steube, a Republican from Florida, on his pitching at the recent Congressional Baseball Game. (The GOP won 31–11.) Oh, hey, here’s South Dakota senator Mike Rounds—“Mike and I have known each other for 22 years,” Smith says. And look, it’s Texas congressman Ronny Jackson. Trump’s former White House physician makes sure to tell me he doesn’t eat the steak here—he prefers the sesame seared tuna. “That’s all I eat,” he says.

After each encounter, Smith licks his fingers, then gestures a check mark in the air, as if ticking off red states on an electoral map. Senator Ted Cruz will surely show up before his 9 pm Hannity hit, Smith tells me. (He doesn’t, but I did spot him a few weeks earlier—he’s a regular.)

After our martinis, we head for Table 3-3, a prime leather booth with a direct view of the herds of suits. Smith, founder of the lobbying and corporate-consulting firm Da Vinci Group, has been a regular here since the first Clinton administration. He also briefly owned another famous restaurant down the street: Signatures, which he and a few others bought from disgraced Republican lobbyist Jack Abramoff in the wake of a corruption scandal that involved free meals for members of Congress. (Smith came in with a new mantra: “Bring your wallet.”)

Smith met his wife, then a lobbyist, at the Capital Grille, and they had their first date here, too. His son, a lobbyist for the firearms industry, was in just yesterday. He shows me photos of himself dining here with his pal Doug Stamper—or rather Michael Kelly, the actor who played him on House of Cards. This is, after all, exactly the kind of place a nefarious political operative would hang out.

“Senator!” Smith calls out. It’s Katie Britt, the Republican senator from Alabama, all smiles and dimples with a glittering cross around her neck. Smith tells her how important her future is to the party, expresses pity over their fumbling political opposition (Britt agrees: “I actually hate for America where we are”), casually mentions his recent 12-day wine trip to Bordeaux, and name-drops his “border security” client, GEO Group, one of the country’s largest operators of private prisons. Britt continues schmoozing around the room, doling out hugs to the lobbyists at the table next to us.

It’s not all Republicans, though. “TOM!” Smith has never met Tom Suozzi, the New York Democrat who won George Santos’s seat, but he knows he’s more likely to get his attention if he calls him by his first name. Suozzi, who’s dining with two fellow Dems and a Republican, says he’s not a regular here. “I’m interested in the scene. I’m observing it,” he tells me. And what are his observations?

“Everybody’s hammered. I haven’t had enough to drink yet.”

If Washington is the swamp, its steakhouses are the alligator pits. While a fresh generation of diverse and trendy restaurants have helped shake the local food scene’s longtime steak-and-potatoes reputation, steakhouses have persisted—fueled in no small part by the ever-changing cast of politicos who frequent them. They’re places where alliances are forged, lawmakers are lobbied, and gobs of money are raised. They’re also country clubs of sorts, each with its own loyal membership.

In particular, Republicans are associated with red meat, a stereotype buoyed by BLT Prime in the Trump hotel—the MAGA hub during the Trump years—and the former President’s own affinity for a well-done filet. Steakhouses have become not just meeting points but talking points in the culture wars. Trump has repeatedly suggested that beef is one more thing Kamala Harris is coming for: “She wants the government to stop people from eating red meat. She wants to get rid of your cows. No more cows.”

The data actually supports partisan perceptions. Campaign-finance reports reveal that Republicans overwhelmingly outspend Democrats at every major steakhouse in the city, including Charlie Palmer Steak; Joe’s Seafood, Prime Steak & Stone Crab; Rare Steakhouse; the Palm; and Bobby Van’s. At the Capital Grille, Republicans have outspent Democrats nearly 13 to 1 so far this election cycle, with bills totaling more than $762,000. Want to know where the right will congregate if there’s a second Trump administration but no more Trump hotel? Well, follow the money . . . and the meat. Because yes, there’s a lot at stake this election—but there’s also a lot of steak.

“You Eat Beef or You Don’t Eat Nothing”

Steakhouses first became prominent in Washington in the early 20th century. The granddaddy of them all: the Occidental, originally located next door to the Willard hotel. When it opened in 1912, it was literally an old boys’ club—for its first three years, no women were allowed within its mahogany walls. The Occidental was the first restaurant in DC to have a commercial electric stove and the first to hang signed portraits of its famous clientele, including then-President Woodrow Wilson, on the walls—a tradition of showing off power later replicated by the likes of the Monocle and the Palm.

During World War II, steakhouses were hit by the strict rationing of beef. But by the 1950s, the restrictions had been lifted. Meanwhile, more modern farming techniques and expanded rail systems emerging from the Midwest made steak cheaper and more accessible. That’s when Blackie’s House of Beef debuted. The West End steakhouse had a lot of a fancy restaurant’s trappings but was affordable enough to attract the masses. “It was the perfect formula,” says DC historian and author John DeFerrari. “And people on a middle-class budget could afford to go there for special occasions and feel like they’re on top of the world.” It helped to have a charismatic owner: Ulysses “Blackie” Auger, whose motto was “You eat beef or you don’t eat nothing.” The steakhouse quickly established itself as the center for Washington hobnobbing, counting FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and Vice President Hubert Humphrey among its regulars.

As far as DeFerrari is aware, though, DC steakhouses weren’t particularly partisan for most of their history. “They were favorites of both sides of the aisle,” he says. “It was much more a matter of prestige and macho culture than political leanings.”

Washington’s steakhouses are where alliances are forged, lawmakers are lobbied, and gobs of money are raised.

It’s hard to say for sure exactly when steakhouses starting tilting Republican, but in 1993, Blackie’s became home to the city’s first “Rush Room,” where fans of Rush Limbaugh could enjoy a steak lunch while absorbing the conservative talk-show host’s midday spewings against “feminazis” and “commie libs.” “I love the fact that Washington’s first Rush Room serves beef,” Limbaugh said on air at the time, according to the Washington Post.

When the Capital Grille opened its third location on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1994, it happened to coincide perfectly with the “Republican Revolution.” The GOP had gained control of the House and Senate for the first time in 40 years, and many players—including the new House speaker, Newt Gingrich—made the steakhouse their spot. “I’d probably drop by every two or three weeks,” Gingrich says. “They had some small rooms you could use, and there was no place competitive with them in that part of the city at that time.”

He also worked out an arrangement to have the steakhouse prepare his go-to porterhouse to go: “You’d get a very good meal while you’re sitting in the speaker’s office. I used to have meetings till 10 or 11 o’clock at night. So that made life better.”

Even though the Capital Grille has always aimed to remain bipartisan, Stephen Fedorchak, the general manager in the late ’90s, was aware of the restaurant’s popularity among Republicans. Still, he remembers plenty of aisle-crossing: “There were a lot of Dems in there as well as a lot of R’s—and not infrequently together, hanging out, having a good time, putting the day’s business behind them. It was collegial and perhaps indicative of a different climate politically.”

Longtime Capital Grille regular David Safavian remembers the same. But things changed, says the American Conservative Union’s general counsel, as the District became more of a dining destination—and politics became more divisive. “Conservatives tend not to really care about the ‘foodie’ culture as much as Democrats do—we would rather just go have a good steak and a glass of wine,” Safavian says. “Back when the city was more bipartisan, Capital Grille reflected that. As the city has become more polarized, I think Republicans go to more traditional establishments.”

In today’s politics, you are what you eat: Obama, the arugula guy, versus Trump, the fast-food junkie. The Chick-fil-A conservatives versus the vegan liberals. Steak, too, is regularly served up with identity politics. Just listen to Ted Cruz—whose PAC has spent tens of thousands of dollars at steakhouses this election cycle—on Fox News: “Kamala can’t have my guns, she can’t have my gasoline engine, and she sure as hell can’t have my steaks and cheeseburgers.”

Steakhouses are one more flash point in our increasingly polarized politics. We’ve become siloed within our own partisan beliefs, consuming news (and food) that agrees with our worldviews, which are reinforced by social-media algorithms. Even the restaurants where we eat can start to feel like political camps. Yes, a steakhouse can still just be a destination for a great rib eye on your birthday—but it can also lead you down a right-wing rabbit hole. It’s red-state cattle country. It’s cowboys over carbon emissions. It’s taxidermy and gun rights. It’s high tax brackets and expense accounts. It’s tradition and masculinity. It’s America First (never mind if the cooks and valets are immigrants). It’s Trump with a side of ketchup.

“There Was Money Everywhere”

Donald Trump visited a single DC restaurant during his four years in office: the steakhouse in his own hotel. Because of that, no restaurant has ever felt more blatantly partisan than BLT Prime.

The Trump hotel wasn’t originally supposed to have a steakhouse. It was supposed to have a José Andrés restaurant. But then Trump announced his bid for President with inflammatory remarks about Mexican immigrants, and the celebrity chef made an abrupt exit that escalated into a headline-grabbing legal battle between the two sides. Moving into a Trump property became toxic to most high-end restaurant operators. Then came BLT Prime and its celebrity-chef partner, David Burke, who was still reminiscing about the time he prepared foie gras and tuna tartare aboard Trump’s yacht, the Trump Princess, in the 1980s. It just so happened that a steakhouse was the perfect restaurant for a President whose main food group seemed to be red meat.

Trump’s BLT Prime Booth was off-limits to anyone except his inner circle, and the staff followed a seven-step process with photo-illustrations for pouring his Diet Coke.

Some Republicans talk about the Trump hotel as if it were the Roman Empire. On any given evening, you might spot Florida congressman Matt Gaetz and the MyPillow Guy in the lobby taking selfies, or White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and American Conservative Union chairman Matt Schlapp dining on the steakhouse’s mezzanine. Rudy Giuliani was there so often that someone made him a plaque reading RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI PRIVATE OFFICE, which the restaurant kept behind the host stand and placed at his table before he arrived. And then, of course, there was Trump himself, the most famous Republican steak lover. His booth, Table 72, was off-limits to anyone except his inner circle, and the staff followed written instructions for serving the commander in chief, including a seven-step process with photo-illustrations for pouring his Diet Coke. (Step one: “The beverage will always be opened in front of POTUS, never beforehand.”)

The MAGA hangers-on would congregate at the lobby bar drinking $23 martinis, hoping to get a nod from someone they knew, says Ethan Lane, VP of government affairs at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, whose office is a block away. There was a palpable sense among that crowd, Lane says, that “if I’m there on the right night, lightning’s going to strike and I’m going to be with the Trump kids eating a well-done steak up in the BLT loft.”

It wasn’t just BLT Prime that thrived during the Trump years (at least until the pandemic put a damper on dining out). “When Trump was in office, I made the most money I’ve ever made in this place,” says an employee of another prominent local steakhouse, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to talk to the media. “The Trump days, it was always the Pappy Van Winkles, you know, the top-of-the-line bourbons and liquors.”

When Trump first came into office, one of his donors bought out the steakhouse, the anonymous employee says: “There was money everywhere. They would shake hands, leave you $100.” One of the swankiest affairs he worked was a Fox News party, attended by the network’s top talking heads: “The lighting was very nice . . . newspeople always have their lighting pretty good.”

In general, Republicans spend more and tip well, the steakhouse employee says. For private events, Republicans tend to splurge on more expensive prix fixe options than Democrats do—and maybe add on some Macallan Scotch. “Depends on which senator or congressman comes in, but it’s always lavish,” the employee says. “They go for the top things and spend top dollar for the wine, the top packages, the best steaks. They spare no expense.”

White House–adjacent BLT Steak, the sister restaurant to BLT Prime, also flourished in the Trump era. The steakhouse had been a favorite of Michelle Obama, who celebrated her 48th birthday there when she was First Lady. But in the years leading up to its closure this summer, former chef Michael Bonk says, ownership would quip to him, “Vote Republican because it’ll keep our private-events business open.”

Bonk says Sarah Huckabee Sanders, then the Trump White House’s press secretary, came into the restaurant not long after she’d famously gotten kicked out of the Red Hen in Lexington, Virginia, for her politics. At least some of the staff were riled up about her presence: “ ‘F— her. I’m not waiting on her. We should kick her out,’ ” Bonk recalls one server saying. But Bonk prides himself on staying above politics in the dining room, so he brought Sanders an extra dish and checked in on her after her meal. He says she seemed so grateful to be in a restaurant where she wasn’t ostracized that she stood up and hugged the chef. “That was interesting,” Bonk says. “I didn’t expect that to happen.”

Another time, Trump lawyers John Dowd and Ty Cobb—the latter a BLT Steak regular—were talking loudly about how to handle the special counsel’s investigation into Russian election interference over lunch on the patio. They happened to be seated near a New York Times reporter, who later published details of the eavesdropped conversation. After that, Bonk says, upper management sent a directive to be hyper-aware of the reservation names and the seating chart. The staff was told not to place newspeople next to potential newsmakers if they could avoid it.

Bonk sometimes lent a hand at BLT Prime, too. He happened to be there helping serve bacon and eggs to Donald Jr. and Eric Trump on the morning of the January 6 insurrection. “They were there for, like, six hours that day,” Bonk says. “People were coming in and out. I think Giuliani came in there at one point in time.”

When Trump supporters started storming the Capitol, however, the hotel was locked down. “People were scared,” Bonk says. “Nobody knew what was going on. People thought it was going to be a war breaking out.” That left the venue with an eerie quiet—and between Trump’s departure and the pandemic’s persistence, it never seemed to fully recover. The following year, the steakhouse closed and the hotel was sold.

“Every Eye Is on You”

DC’s current steakhouse scene spans from foodie destinations like St. Anselm, where the salmon collar is a specialty, to nightclub-style spots like STK, which brands itself the “leader in vibe dining.” There’s Joe’s, next to the White House, with its bustling half-price happy hour and curtained corner booth dubbed the “rock-star table” because Bono once sat there. There’s Charlie Palmer, which differentiates itself with its bright, modern aesthetic and rooftop terrace for events. There’s also Morton’s downtown, where the K Street crowd smokes cigars on the patio and abortion-rights activists once chased away Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh after Roe v. Wade was overturned.

Top Spenders

Which members of Congress and political groups have spent the most at the Capital Grille this election cycle? Check out their political-action committees’ campaign-finance filings.

$130,336

House Majority Leader

Steve Scalise

(R-Louisiana)

$40,964

Building Bridges PAC

(donates to GOP candidates)

$28,822

Congressman

Mike Rogers

(R-Alabama)

$20,240

Senator

John Thune

(R-South Dakota)

$17,278

Congressman

Rob Wittman

(R-Virginia)

Source: OpenSecrets

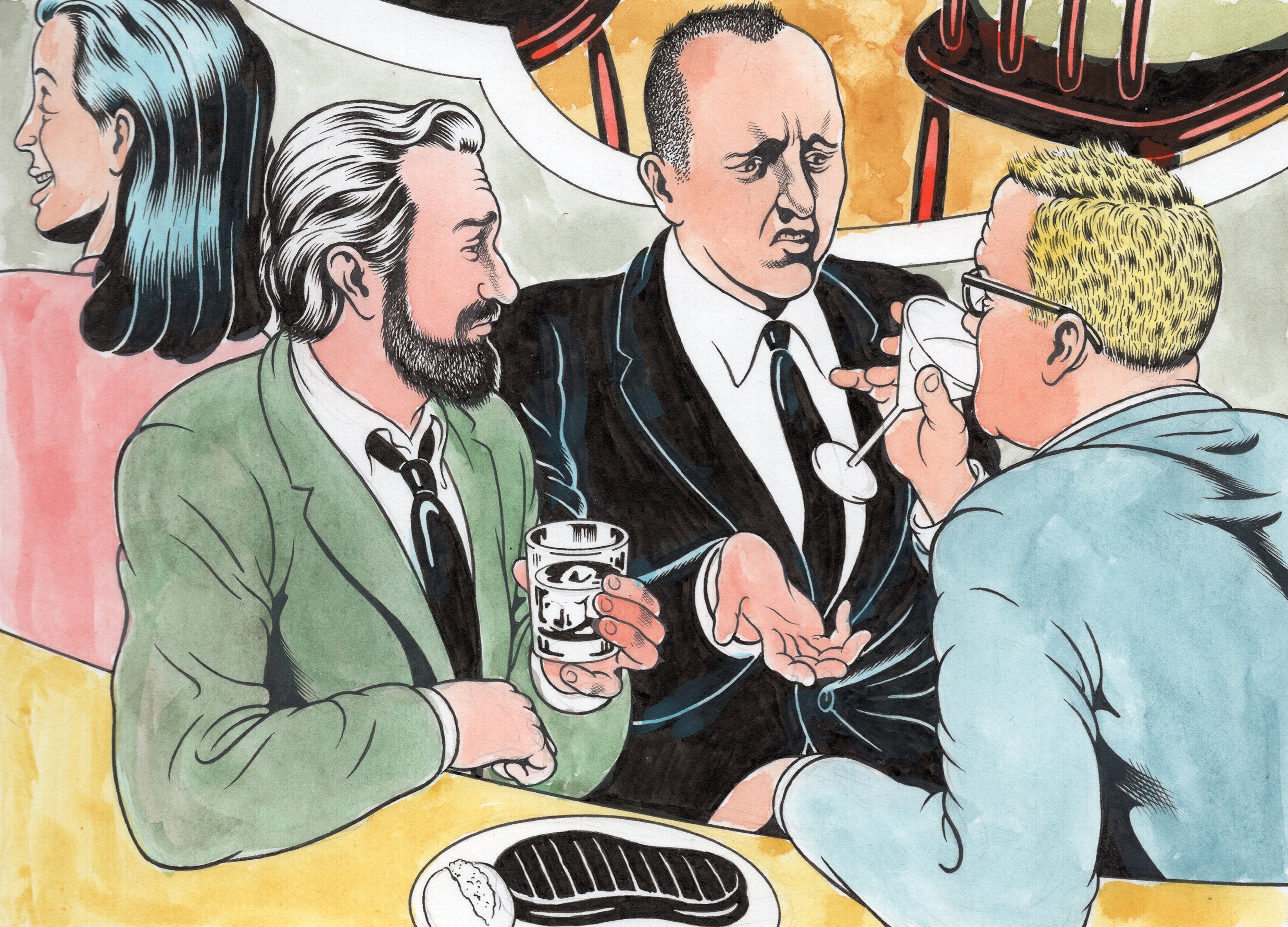

But the Capital Grille on Pennsylvania Avenue is the quintessential steakhouse, straight out of a movie—in fact, the spy thriller Jason Bourne filmed there. It’s decisively masculine, with dark wood, taxidermied animals on the walls, and wine lockers for stocking bottles of Brunello and bragging rights.

“I don’t think that there’s another more Republican hangout than the Capital Grille—bar none,” says David Safavian of the American Conservative Union. “It just feels the way a steakhouse should.” As of mid-2024, Republican PACs had spent more than $762,000 at the steakhouse this election cycle, compared with the roughly $59,000 Democrats spent, according to OpenSecrets data.

Safavian argues that the Capital Grille was the biggest beneficiary of BLT Prime’s shuttering. But in its own way, it has long been more of a Republican hub than the Trump hotel and its steakhouse ever were. “[The Trump hotel] wasn’t a Hill environment. It was a Trump-world environment,” says Lane, the beef lobbyist. “The Capital Grille scene is very much a Hill environment. It is chiefs of staff. It is members of Congress. It is senators. And it is lobbyists. That is a very different dynamic than something that’s oriented towards an individual or movement.”

The Pennsylvania Avenue address makes it easy for a member to pop in and zip back to the Capitol for a vote, and the two private rooms fill nearly every night Congress is in session with political fundraisers and fly-ins. The bar is its own ecosystem rife with lobbyists, political operatives, and other regulars. “There’s a lot of lobbyists that fly in for the part of the week that’s in session and then fly back home,” Lane says. “And that’ll be their second office when they’re in town. You can almost set your watch to who you’re going to see at certain times of the day or night in an in-session week, just because you know that’s where they hold court.”

That’s nothing compared with what one lobbying firm did. Venture Government Strategies—whose partners include former Republican congressmen Ben Quayle (son of former VP Dan Quayle) and Kevin Yoder (cofounder of the Congressional Beef Caucus)—not only moved their offices above the Capital Grille last year, they also hired the longtime maître d’ as their director of operations and events. Yoder told Politico it was “a great access point for our clients as they engage with key policymakers.”

At most area restaurants, elected officials are afforded a certain level of privacy. If Lane runs into a senator at his neighborhood pizzeria in Old Town, he’s not going to run over to the table to discuss HR-2437. But at the Capital Grille? Lane doesn’t know much about Los Angeles culture, but he knows this: “If celebrities want to have photos taken of them, they go to the Ivy. And to some extent, that is Capital Grille as well. No one ever went to Capital Grille to hide in the corner and have a quiet dinner. Every eye is on you.”

At the Capital Grille, “You can almost set your watch to who you’re going to see at certain times of the day or night in an in-session week, just because you know that’s where they hold court.”

Earlier this year, Lane had dinner with a senator at the Capital Grille. “He’s well known enough that it took him a full 15 minutes to work his way through the restaurant, because every table—even people he didn’t know—were grabbing him and wanting to have a few words or get a picture. And then as soon as we sat down and started talking, people were coming over to have private conversations. It was like, ‘I have to deliver this urgent information to you.’ ”

The steakhouse scene also can have a dark side, an icky swampiness to the wheeling, dealing, and showy expense of it all. The most famous example in recent history centered around Senator Bob Menendez, who reportedly ate on the smoker-friendly patio of Morton’s steakhouse downtown 250 nights a year. It was there that undercover FBI agents collected evidence for corruption charges against the New Jersey Democrat, who was later convicted on 16 counts including bribery, extortion, acting as a foreign agent for Egypt, and obstruction of justice.

Creatures of the steakhouse are also easy targets for attack lines about special interests and overspending. “When Democrats do fundraising, we want the money to go into our campaigns, not into a steakhouse,” says Democratic senator Ben Cardin of Maryland. “And quite frankly, our donor base doesn’t always have that type of money to be able to afford for us to have a fundraiser at a steakhouse.” He prefers to do events at Attman’s Delicatessen in Potomac, though plenty of Dems host fundraisers at fancy restaurants, too—often newer, trendier places.

It’s not just Democrats throwing shade at Washington’s steak-filled rooms. As Republicans scrambled to find a new speaker of the House last year following the ouster of Kevin McCarthy, allies of far-right congressman Jim Jordan attempted to sabotage House majority leader Steve Scalise’s bid for the job by broadcasting his steakhouse spending. Since 2011, Scalise’s congressional campaign has dropped more than $500,000 at the Capital Grille.

When that restaurant opened 30 years ago, you could still smoke in the dining room and buy a Congress member dinner without fear of an ethics investigation. That changed in the wake of the Jack Abramoff scandal, when Congress passed a ban on meals or gifts from lobbyists to lawmakers. But the new rules didn’t make the steakhouse any less of a lobbyist hub.

“Capital Grille’s been a center point for lobbyist schmoozing way before my time,” says Craig Holman of the government watchdog group Public Citizen, who was involved in drafting the 2008 gift ban. In the years since, he says he’s frequently heard rumors about wink-and-a-nod evasion of the rules at steakhouses and other expensive restaurants around the city. “It makes me wonder if they are, in fact, getting around these gift rules, making payment arrangements through some means that isn’t obvious or easily monitored, or even basically staging things like campaign fundraisers that are really meant as lobbyist schmoozing events,” he says. “It raises red flags.”

“Drinking Bourbon out the Ying-Yang”

Over our steak dinner in July, when all anyone could talk about was Joe Biden’s disastrous debate, Smith, the lobbyist, was already plotting out Trump’s Cabinet picks and congressional-committee chairs. I asked if he was going to the Republican National Convention the following week. He just laughed.

“I can see all those people here.”

By the time the Democratic National Convention rolled around in August and Harris was the hot new presidential contender, Smith was still confident of a GOP sweep of Congress and the White House. But whoever ended up in power, he said, the Capital Grille would remain Cheers for him and many of his fellow Republicans: “Capital Grill is like the Washington Monument. It is a staple of the city. Not only will it survive, I think it will continue to thrive and do very good business. You still have to raise money. Tourists will still come there. Businesspeople will go there.”

As for Trump? If he does win in November, there’s a good chance he might never venture out to eat beyond the White House in deep-blue DC, given the lack of Washington hotels bearing his name. (Just as well: He once called 1600 Penn “the greatest restaurant.”) But there’s still plenty of speculation about where an influx of red-hatters and conservative Cabinet secretaries might congregate in DC if the former President is reelected.

The Waldorf Astoria, which replaced the Trump hotel, may draw a MAGA crowd out of habit, never mind that José Andrés reclaimed the lobby steakhouse space. Georgetown institution Cafe Milano—dubbed the “second White House cafeteria” by the New York Post in 2017 thanks to appearances by former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, and others—plays lunch lady to whoever is in power. And there could be a newbie contender: A Trump-loyalist group called the Conservative Partnership Institute has bought up real estate in Capitol Hill to build its own mini-MAGAville dubbed “Patriots’ Row,” which includes plans for a restaurant in the former Capitol Lounge space.

Don’t be surprised to see a steakhouse bump, too. At the end of the Obama presidency, the manager of one steakhouse remembers seeing the restaurant’s TVs playing footage of the First Family leaving the White House for the last time. “ ‘Yeah, get away—go,’ ” he recalls some Republican women at the bar cheering while they mocked Michelle Obama. Over at the Capital Grille, Smith says a celebratory atmosphere extended weeks after Trump beat Hillary Clinton: “We’re talking, like, Château Margaux bottles being opened up and down the bar. People were drinking bourbon out the ying-yang, just screaming their heads off. It was an extended spike-the-football moment.”

The thing about restaurants, though, is that they’re there for you whether you’re up or down. When I finally convince Smith to at least hypothetically imagine a world where Trump loses, he can still envision whiskey out the ying-yang come November 6—though for different reasons, obviously.

“It’ll be ‘Oh, shit,’ ” Smith says. “Then they’ll turn and go, ‘Hey, bartender, give me another Scotch.’ ”

Beneath a giant buffalo bust, Republican lobbyist Mark Smith sips a three-olive Belvedere martini at the bar of DC’s Capital Grille, ready for his own kind of hunt. Congress is in session this Wednesday in July—just before the assassination attempt on Donald Trump and the abrupt exit of Joe Biden from the presidential race—and the place is packed.

Smith shakes hands with a former Trump Labor Department official. He congratulates Congressman Greg Steube, a Republican from Florida, on his pitching at the recent Congressional Baseball Game. (The GOP won 31–11.) Oh, hey, here’s South Dakota senator Mike Rounds—“Mike and I have known each other for 22 years,” Smith says. And look, it’s Texas congressman Ronny Jackson. Trump’s former White House physician makes sure to tell me he doesn’t eat the steak here—he prefers the sesame seared tuna. “That’s all I eat,” he says.

After each encounter, Smith licks his fingers, then gestures a check mark in the air, as if ticking off red states on an electoral map. Senator Ted Cruz will surely show up before his 9 pm Hannity hit, Smith tells me. (He doesn’t, but I did spot him a few weeks earlier—he’s a regular.)

After our martinis, we head for Table 3-3, a prime leather booth with a direct view of the herds of suits. Smith, founder of the lobbying and corporate-consulting firm Da Vinci Group, has been a regular here since the first Clinton administration. He also briefly owned another famous restaurant down the street: Signatures, which he and a few others bought from disgraced Republican lobbyist Jack Abramoff in the wake of a corruption scandal that involved free meals for members of Congress. (Smith came in with a new mantra: “Bring your wallet.”)

Smith met his wife, then a lobbyist, at the Capital Grille, and they had their first date here, too. His son, a lobbyist for the firearms industry, was in just yesterday. He shows me photos of himself dining here with his pal Doug Stamper—or rather Michael Kelly, the actor who played him on House of Cards. This is, after all, exactly the kind of place a nefarious political operative would hang out.

“Senator!” Smith calls out. It’s Katie Britt, the Republican senator from Alabama, all smiles and dimples with a glittering cross around her neck. Smith tells her how important her future is to the party, expresses pity over their fumbling political opposition (Britt agrees: “I actually hate for America where we are”), casually mentions his recent 12-day wine trip to Bordeaux, and name-drops his “border security” client, GEO Group, one of the country’s largest operators of private prisons. Britt continues schmoozing around the room, doling out hugs to the lobbyists at the table next to us.

It’s not all Republicans, though. “TOM!” Smith has never met Tom Suozzi, the New York Democrat who won George Santos’s seat, but he knows he’s more likely to get his attention if he calls him by his first name. Suozzi, who’s dining with two fellow Dems and a Republican, says he’s not a regular here. “I’m interested in the scene. I’m observing it,” he tells me. And what are his observations?

“Everybody’s hammered. I haven’t had enough to drink yet.”

If Washington is the swamp, its steakhouses are the alligator pits. While a fresh generation of diverse and trendy restaurants have helped shake the local food scene’s longtime steak-and-potatoes reputation, steakhouses have persisted—fueled in no small part by the ever-changing cast of politicos who frequent them. They’re places where alliances are forged, lawmakers are lobbied, and gobs of money are raised. They’re also country clubs of sorts, each with its own loyal membership.

In particular, Republicans are associated with red meat, a stereotype buoyed by BLT Prime in the Trump hotel—the MAGA hub during the Trump years—and the former President’s own affinity for a well-done filet. Steakhouses have become not just meeting points but talking points in the culture wars. Trump has repeatedly suggested that beef is one more thing Kamala Harris is coming for: “She wants the government to stop people from eating red meat. She wants to get rid of your cows. No more cows.”

The data actually supports partisan perceptions. Campaign-finance reports reveal that Republicans overwhelmingly outspend Democrats at every major steakhouse in the city, including Charlie Palmer Steak; Joe’s Seafood, Prime Steak & Stone Crab; Rare Steakhouse; the Palm; and Bobby Van’s. At the Capital Grille, Republicans have outspent Democrats nearly 13 to 1 so far this election cycle, with bills totaling more than $762,000. Want to know where the right will congregate if there’s a second Trump administration but no more Trump hotel? Well, follow the money . . . and the meat. Because yes, there’s a lot at stake this election—but there’s also a lot of steak.

Top Spenders

Which members of Congress and political groups have spent the most at the Capital Grille this election cycle? Check out their political-action committees’ campaign-finance filings.

$130,336

House Majority Leader

Steve Scalise

(R-Louisiana)

$40,964

Building Bridges PAC

(donates to GOP candidates)

$28,822

Congressman

Mike Rogers

(R-Alabama)

$20,240

Senator

John Thune

(R-South Dakota)

$17,278

Congressman

Rob Wittman

(R-Virginia)

Source: OpenSecrets

“You Eat Beef or You Don’t Eat Nothing”

Steakhouses first became prominent in Washington in the early 20th century. The granddaddy of them all: the Occidental, originally located next door to the Willard hotel. When it opened in 1912, it was literally an old boys’ club—for its first three years, no women were allowed within its mahogany walls. The Occidental was the first restaurant in DC to have a commercial electric stove and the first to hang signed portraits of its famous clientele, including then-President Woodrow Wilson, on the walls—a tradition of showing off power later replicated by the likes of the Monocle and the Palm.

During World War II, steakhouses were hit by the strict rationing of beef. But by the 1950s, the restrictions had been lifted. Meanwhile, more modern farming techniques and expanded rail systems emerging from the Midwest made steak cheaper and more accessible. That’s when Blackie’s House of Beef debuted. The West End steakhouse had a lot of a fancy restaurant’s trappings but was affordable enough to attract the masses. “It was the perfect formula,” says DC historian and author John DeFerrari. “And people on a middle-class budget could afford to go there for special occasions and feel like they’re on top of the world.” It helped to have a charismatic owner: Ulysses “Blackie” Auger, whose motto was “You eat beef or you don’t eat nothing.” The steakhouse quickly established itself as the center for Washington hobnobbing, counting FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and Vice President Hubert Humphrey among its regulars.

As far as DeFerrari is aware, though, DC steakhouses weren’t particularly partisan for most of their history. “They were favorites of both sides of the aisle,” he says. “It was much more a matter of prestige and macho culture than political leanings.”

Washington’s steakhouses are where alliances are forged, lawmakers are lobbied, and gobs of money are raised.

It’s hard to say for sure exactly when steakhouses starting tilting Republican, but in 1993, Blackie’s became home to the city’s first “Rush Room,” where fans of Rush Limbaugh could enjoy a steak lunch while absorbing the conservative talk-show host’s midday spewings against “feminazis” and “commie libs.” “I love the fact that Washington’s first Rush Room serves beef,” Limbaugh said on air at the time, according to the Washington Post.

When the Capital Grille opened its third location on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1994, it happened to coincide perfectly with the “Republican Revolution.” The GOP had gained control of the House and Senate for the first time in 40 years, and many players—including the new House speaker, Newt Gingrich—made the steakhouse their spot. “I’d probably drop by every two or three weeks,” Gingrich says. “They had some small rooms you could use, and there was no place competitive with them in that part of the city at that time.”

He also worked out an arrangement to have the steakhouse prepare his go-to porterhouse to go: “You’d get a very good meal while you’re sitting in the speaker’s office. I used to have meetings till 10 or 11 o’clock at night. So that made life better.”

Even though the Capital Grille has always aimed to remain bipartisan, Stephen Fedorchak, the general manager in the late ’90s, was aware of the restaurant’s popularity among Republicans. Still, he remembers plenty of aisle-crossing: “There were a lot of Dems in there as well as a lot of R’s—and not infrequently together, hanging out, having a good time, putting the day’s business behind them. It was collegial and perhaps indicative of a different climate politically.”

Longtime Capital Grille regular David Safavian remembers the same. But things changed, says the American Conservative Union’s general counsel, as the District became more of a dining destination—and politics became more divisive. “Conservatives tend not to really care about the ‘foodie’ culture as much as Democrats do—we would rather just go have a good steak and a glass of wine,” Safavian says. “Back when the city was more bipartisan, Capital Grille reflected that. As the city has become more polarized, I think Republicans go to more traditional establishments.”

In today’s politics, you are what you eat: Obama, the arugula guy, versus Trump, the fast-food junkie. The Chick-fil-A conservatives versus the vegan liberals. Steak, too, is regularly served up with identity politics. Just listen to Ted Cruz—whose PAC has spent tens of thousands of dollars at steakhouses this election cycle—on Fox News: “Kamala can’t have my guns, she can’t have my gasoline engine, and she sure as hell can’t have my steaks and cheeseburgers.”

Steakhouses are one more flash point in our increasingly polarized politics. We’ve become siloed within our own partisan beliefs, consuming news (and food) that agrees with our worldviews, which are reinforced by social-media algorithms. Even the restaurants where we eat can start to feel like political camps. Yes, a steakhouse can still just be a destination for a great rib eye on your birthday—but it can also lead you down a right-wing rabbit hole. It’s red-state cattle country. It’s cowboys over carbon emissions. It’s taxidermy and gun rights. It’s high tax brackets and expense accounts. It’s tradition and masculinity. It’s America First (never mind if the cooks and valets are immigrants). It’s Trump with a side of ketchup.

“There Was Money Everywhere”

Donald Trump visited a single DC restaurant during his four years in office: the steakhouse in his own hotel. Because of that, no restaurant has ever felt more blatantly partisan than BLT Prime.

The Trump hotel wasn’t originally supposed to have a steakhouse. It was supposed to have a José Andrés restaurant. But then Trump announced his bid for President with inflammatory remarks about Mexican immigrants, and the celebrity chef made an abrupt exit that escalated into a headline-grabbing legal battle between the two sides. Moving into a Trump property became toxic to most high-end restaurant operators. Then came BLT Prime and its celebrity-chef partner, David Burke, who was still reminiscing about the time he prepared foie gras and tuna tartare aboard Trump’s yacht, the Trump Princess, in the 1980s. It just so happened that a steakhouse was the perfect restaurant for a President whose main food group seemed to be red meat.

Trump’s BLT Prime Booth was off-limits to anyone except his inner circle, and the staff followed a seven-step process with photo-illustrations for pouring his Diet Coke.

Some Republicans talk about the Trump hotel as if it were the Roman Empire. On any given evening, you might spot Florida congressman Matt Gaetz and the MyPillow Guy in the lobby taking selfies, or White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and American Conservative Union chairman Matt Schlapp dining on the steakhouse’s mezzanine. Rudy Giuliani was there so often that someone made him a plaque reading RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI PRIVATE OFFICE, which the restaurant kept behind the host stand and placed at his table before he arrived. And then, of course, there was Trump himself, the most famous Republican steak lover. His booth, Table 72, was off-limits to anyone except his inner circle, and the staff followed written instructions for serving the commander in chief, including a seven-step process with photo-illustrations for pouring his Diet Coke. (Step one: “The beverage will always be opened in front of POTUS, never beforehand.”)

The MAGA hangers-on would congregate at the lobby bar drinking $23 martinis, hoping to get a nod from someone they knew, says Ethan Lane, VP of government affairs at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, whose office is a block away. There was a palpable sense among that crowd, Lane says, that “if I’m there on the right night, lightning’s going to strike and I’m going to be with the Trump kids eating a well-done steak up in the BLT loft.”

It wasn’t just BLT Prime that thrived during the Trump years (at least until the pandemic put a damper on dining out). “When Trump was in office, I made the most money I’ve ever made in this place,” says an employee of another prominent local steakhouse, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to talk to the media. “The Trump days, it was always the Pappy Van Winkles, you know, the top-of-the-line bourbons and liquors.”

When Trump first came into office, one of his donors bought out the steakhouse, the anonymous employee says: “There was money everywhere. They would shake hands, leave you $100.” One of the swankiest affairs he worked was a Fox News party, attended by the network’s top talking heads: “The lighting was very nice . . . newspeople always have their lighting pretty good.”

In general, Republicans spend more and tip well, the steakhouse employee says. For private events, Republicans tend to splurge on more expensive prix fixe options than Democrats do—and maybe add on some Macallan Scotch. “Depends on which senator or congressman comes in, but it’s always lavish,” the employee says. “They go for the top things and spend top dollar for the wine, the top packages, the best steaks. They spare no expense.”

White House–adjacent BLT Steak, the sister restaurant to BLT Prime, also flourished in the Trump era. The steakhouse had been a favorite of Michelle Obama, who celebrated her 48th birthday there when she was First Lady. But in the years leading up to its closure this summer, former chef Michael Bonk says, ownership would quip to him, “Vote Republican because it’ll keep our private-events business open.”

Bonk says Sarah Huckabee Sanders, then the Trump White House’s press secretary, came into the restaurant not long after she’d famously gotten kicked out of the Red Hen in Lexington, Virginia, for her politics. At least some of the staff were riled up about her presence: “ ‘F— her. I’m not waiting on her. We should kick her out,’ ” Bonk recalls one server saying. But Bonk prides himself on staying above politics in the dining room, so he brought Sanders an extra dish and checked in on her after her meal. He says she seemed so grateful to be in a restaurant where she wasn’t ostracized that she stood up and hugged the chef. “That was interesting,” Bonk says. “I didn’t expect that to happen.”

Another time, Trump lawyers John Dowd and Ty Cobb—the latter a BLT Steak regular—were talking loudly about how to handle the special counsel’s investigation into Russian election interference over lunch on the patio. They happened to be seated near a New York Times reporter, who later published details of the eavesdropped conversation. After that, Bonk says, upper management sent a directive to be hyper-aware of the reservation names and the seating chart. The staff was told not to place newspeople next to potential newsmakers if they could avoid it.

Bonk sometimes lent a hand at BLT Prime, too. He happened to be there helping serve bacon and eggs to Donald Jr. and Eric Trump on the morning of the January 6 insurrection. “They were there for, like, six hours that day,” Bonk says. “People were coming in and out. I think Giuliani came in there at one point in time.”

When Trump supporters started storming the Capitol, however, the hotel was locked down. “People were scared,” Bonk says. “Nobody knew what was going on. People thought it was going to be a war breaking out.” That left the venue with an eerie quiet—and between Trump’s departure and the pandemic’s persistence, it never seemed to fully recover. The following year, the steakhouse closed and the hotel was sold.

“Every Eye Is on You”

DC’s current steakhouse scene spans from foodie destinations like St. Anselm, where the salmon collar is a specialty, to nightclub-style spots like STK, which brands itself the “leader in vibe dining.” There’s Joe’s, next to the White House, with its bustling half-price happy hour and curtained corner booth dubbed the “rock-star table” because Bono once sat there. There’s Charlie Palmer, which differentiates itself with its bright, modern aesthetic and rooftop terrace for events. There’s also Morton’s downtown, where the K Street crowd smokes cigars on the patio and abortion-rights activists once chased away Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh after Roe v. Wade was overturned.

But the Capital Grille on Pennsylvania Avenue is the quintessential steakhouse, straight out of a movie—in fact, the spy thriller Jason Bourne filmed there. It’s decisively masculine, with dark wood, taxidermied animals on the walls, and wine lockers for stocking bottles of Brunello and bragging rights.

“I don’t think that there’s another more Republican hangout than the Capital Grille—bar none,” says David Safavian of the American Conservative Union. “It just feels the way a steakhouse should.” As of mid-2024, Republican PACs had spent more than $762,000 at the steakhouse this election cycle, compared with the roughly $59,000 Democrats spent, according to OpenSecrets data.

Safavian argues that the Capital Grille was the biggest beneficiary of BLT Prime’s shuttering. But in its own way, it has long been more of a Republican hub than the Trump hotel and its steakhouse ever were. “[The Trump hotel] wasn’t a Hill environment. It was a Trump-world environment,” says Lane, the beef lobbyist. “The Capital Grille scene is very much a Hill environment. It is chiefs of staff. It is members of Congress. It is senators. And it is lobbyists. That is a very different dynamic than something that’s oriented towards an individual or movement.”

The Pennsylvania Avenue address makes it easy for a member to pop in and zip back to the Capitol for a vote, and the two private rooms fill nearly every night Congress is in session with political fundraisers and fly-ins. The bar is its own ecosystem rife with lobbyists, political operatives, and other regulars. “There’s a lot of lobbyists that fly in for the part of the week that’s in session and then fly back home,” Lane says. “And that’ll be their second office when they’re in town. You can almost set your watch to who you’re going to see at certain times of the day or night in an in-session week, just because you know that’s where they hold court.”

That’s nothing compared with what one lobbying firm did. Venture Government Strategies—whose partners include former Republican congressmen Ben Quayle (son of former VP Dan Quayle) and Kevin Yoder (cofounder of the Congressional Beef Caucus)—not only moved their offices above the Capital Grille last year, they also hired the longtime maître d’ as their director of operations and events. Yoder told Politico it was “a great access point for our clients as they engage with key policymakers.”

At most area restaurants, elected officials are afforded a certain level of privacy. If Lane runs into a senator at his neighborhood pizzeria in Old Town, he’s not going to run over to the table to discuss HR-2437. But at the Capital Grille? Lane doesn’t know much about Los Angeles culture, but he knows this: “If celebrities want to have photos taken of them, they go to the Ivy. And to some extent, that is Capital Grille as well. No one ever went to Capital Grille to hide in the corner and have a quiet dinner. Every eye is on you.”

At the Capital Grille, “You can almost set your watch to who you’re going to see at certain times of the day or night in an in-session week, just because you know that’s where they hold court.”

Earlier this year, Lane had dinner with a senator at the Capital Grille. “He’s well known enough that it took him a full 15 minutes to work his way through the restaurant, because every table—even people he didn’t know—were grabbing him and wanting to have a few words or get a picture. And then as soon as we sat down and started talking, people were coming over to have private conversations. It was like, ‘I have to deliver this urgent information to you.’ ”

The steakhouse scene also can have a dark side, an icky swampiness to the wheeling, dealing, and showy expense of it all. The most famous example in recent history centered around Senator Bob Menendez, who reportedly ate on the smoker-friendly patio of Morton’s steakhouse downtown 250 nights a year. It was there that undercover FBI agents collected evidence for corruption charges against the New Jersey Democrat, who was later convicted on 16 counts including bribery, extortion, acting as a foreign agent for Egypt, and obstruction of justice.

Creatures of the steakhouse are also easy targets for attack lines about special interests and overspending. “When Democrats do fundraising, we want the money to go into our campaigns, not into a steakhouse,” says Democratic senator Ben Cardin of Maryland. “And quite frankly, our donor base doesn’t always have that type of money to be able to afford for us to have a fundraiser at a steakhouse.” He prefers to do events at Attman’s Delicatessen in Potomac, though plenty of Dems host fundraisers at fancy restaurants, too—often newer, trendier places.

It’s not just Democrats throwing shade at Washington’s steak-filled rooms. As Republicans scrambled to find a new speaker of the House last year following the ouster of Kevin McCarthy, allies of far-right congressman Jim Jordan attempted to sabotage House majority leader Steve Scalise’s bid for the job by broadcasting his steakhouse spending. Since 2011, Scalise’s congressional campaign has dropped more than $500,000 at the Capital Grille.

When that restaurant opened 30 years ago, you could still smoke in the dining room and buy a Congress member dinner without fear of an ethics investigation. That changed in the wake of the Jack Abramoff scandal, when Congress passed a ban on meals or gifts from lobbyists to lawmakers. But the new rules didn’t make the steakhouse any less of a lobbyist hub.

“Capital Grille’s been a center point for lobbyist schmoozing way before my time,” says Craig Holman of the government watchdog group Public Citizen, who was involved in drafting the 2008 gift ban. In the years since, he says he’s frequently heard rumors about wink-and-a-nod evasion of the rules at steakhouses and other expensive restaurants around the city. “It makes me wonder if they are, in fact, getting around these gift rules, making payment arrangements through some means that isn’t obvious or easily monitored, or even basically staging things like campaign fundraisers that are really meant as lobbyist schmoozing events,” he says. “It raises red flags.”

“Drinking Bourbon out the Ying-Yang”

Over our steak dinner in July, when all anyone could talk about was Joe Biden’s disastrous debate, Smith, the lobbyist, was already plotting out Trump’s Cabinet picks and congressional-committee chairs. I asked if he was going to the Republican National Convention the following week. He just laughed.

“I can see all those people here.”

By the time the Democratic National Convention rolled around in August and Harris was the hot new presidential contender, Smith was still confident of a GOP sweep of Congress and the White House. But whoever ended up in power, he said, the Capital Grille would remain Cheers for him and many of his fellow Republicans: “Capital Grill is like the Washington Monument. It is a staple of the city. Not only will it survive, I think it will continue to thrive and do very good business. You still have to raise money. Tourists will still come there. Businesspeople will go there.”

As for Trump? If he does win in November, there’s a good chance he might never venture out to eat beyond the White House in deep-blue DC, given the lack of Washington hotels bearing his name. (Just as well: He once called 1600 Penn “the greatest restaurant.”) But there’s still plenty of speculation about where an influx of red-hatters and conservative Cabinet secretaries might congregate in DC if the former President is reelected.

The Waldorf Astoria, which replaced the Trump hotel, may draw a MAGA crowd out of habit, never mind that José Andrés reclaimed the lobby steakhouse space. Georgetown institution Cafe Milano—dubbed the “second White House cafeteria” by the New York Post in 2017 thanks to appearances by former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, and others—plays lunch lady to whoever is in power. And there could be a newbie contender: A Trump-loyalist group called the Conservative Partnership Institute has bought up real estate in Capitol Hill to build its own mini-MAGAville dubbed “Patriots’ Row,” which includes plans for a restaurant in the former Capitol Lounge space.

Don’t be surprised to see a steakhouse bump, too. At the end of the Obama presidency, the manager of one steakhouse remembers seeing the restaurant’s TVs playing footage of the First Family leaving the White House for the last time. “ ‘Yeah, get away—go,’ ” he recalls some Republican women at the bar cheering while they mocked Michelle Obama. Over at the Capital Grille, Smith says a celebratory atmosphere extended weeks after Trump beat Hillary Clinton: “We’re talking, like, Château Margaux bottles being opened up and down the bar. People were drinking bourbon out the ying-yang, just screaming their heads off. It was an extended spike-the-football moment.”

The thing about restaurants, though, is that they’re there for you whether you’re up or down. When I finally convince Smith to at least hypothetically imagine a world where Trump loses, he can still envision whiskey out the ying-yang come November 6—though for different reasons, obviously.

“It’ll be ‘Oh, shit,’ ” Smith says. “Then they’ll turn and go, ‘Hey, bartender, give me another Scotch.’ ”

This article appears in the October 2024 issue of Washingtonian.