Frank Rich’s 30-year career at the New York Times had

many highlights, but during his first few months as a critic there, he was

convinced that accepting the job had been a mistake.

“I was third-string everything, covering radio, TV, theater—you

name it,” he says. “I was asked by my editor to review a radio show that

aired at 2:30 am on a Sunday.” Rich figured out that the show starred the

newspaper editor’s mistress.

A few months later, in 1980, longtime theater critic Walter

Kerr decided to retire and recommended Rich as his successor. Rich’s

tenure in that job lasted 13 years and earned him the nickname the Butcher

of Broadway.

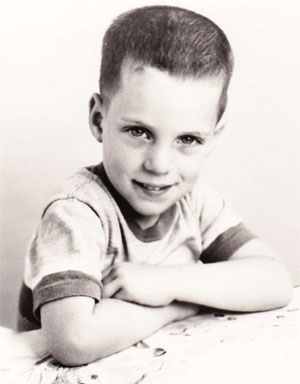

Rich, 63, has lived in New York for four decades but grew up in

Washington in the 1950s and ’60s. He wrote about his childhood, much of it

in DC’s Cleveland Park, in the memoir Ghost Light, published in

2000. His father, Frank Rich Sr., owned the local Rich’s shoe stores, and

his often abusive stepfather was a lawyer on K Street.

Unhappy at home, young Frank Rich found solace in the theater,

saving money from his paper route to buy tickets to Broadway-bound shows

at the National Theatre. Even when he got a job as ticket taker, allowing

him to see shows for free, he paid for admission so he could see the

opening scenes he missed while counting stubs at the start of each

play.

Rich attended Woodrow Wilson High School, where he edited the

school paper, and then Harvard, where he wrote for the Crimson.

After a fellowship in London, he moved to Richmond, where he started an

alternative weekly, the Richmond Mercury. In 1972, he wrote a

cover story for The Washingtonian about Washington’s singles

scene. Rich then moved to New York to be an assistant editor and film

critic at New Times magazine and worked at the New York

Post and Time before joining the New York Times in

1980.

He left the theater desk to write a weekly column for the

opinion section in 1994, remaining at the Times until last year,

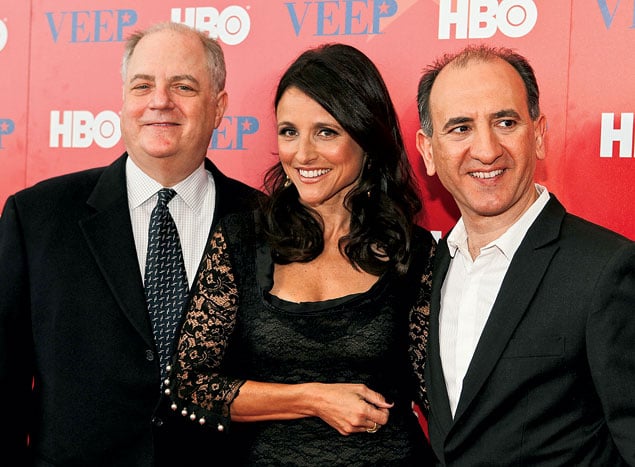

when he became a writer-at-large at New York magazine. He’s also

an executive producer of Veep, HBO’s satire about an inept female

US Vice President, played by Julia Louis-Dreyfus. Rich appears at the

Music Center at Strathmore on October 19 for a conversation with satirist

Fran Lebowitz about the national political landscape.

He has two sons from his first marriage: Simon, a writer for

Saturday Night Live and a contributor to the New Yorker,

and Nathaniel, a novelist. Rich’s wife is New York Times

Magazine writer Alex Witchel. Over iced tea in the bar at

Georgetown’s Four Seasons Hotel, he talked about what he’s

learned.

Do you remember the first show you ever saw?

It was Damn Yankees at the National Theatre. I was

about five or six, and I think my parents took me to see it because I was

a huge Washington Senators fan. It was the ultimate wet dream—although I

didn’t know what wet dreams were back then—that the Senators could beat

the Yankees of Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris and Whitey Ford.

What impression did the musical make on you?

I didn’t understand the story, but I couldn’t get over how the

scenery changed and how Lola could go from this attractive young woman to

this old crone, which happens in the second act. I was hooked. It was a

life-changing experience.

What was the National like then?

In those days, before the Kennedy Center or any of the arts

centers in Boston and Tampa and Cleveland had been built, the National was

it. The National was very popular with producers because you could play to

what was, by the standard of the times, a large house with a sympathetic

audience. David Merrick, the biggest Broadway producer of that era, would

book the National from Labor Day to Christmas, not even knowing whether he

was going to do Hello, Dolly! or Pickwick or

Oliver! or whatever else he had up his sleeve. It was glamorous,

although it’s hard to imagine now.

You grew up all over Washington.

When I was born in 1949, we lived in Somerset, which is part of

Chevy Chase. My parents split up when I was around seven. My mother had to

support herself, so we moved to Rosemary Hills in Silver Spring for a

couple of years.

Then she married, and at the height of white flight we moved to

Cleveland Park. My mother and stepfather bought a house in 1959 for

$29,000 on Cleveland Avenue, between 34th Street and the cathedral. Half

the houses on the block were empty because middle-class white families

were moving to Montgomery County and Arlington and Alexandria. My

stepfather, always glad to have a bargain, moved us in, and I started

fifth and sixth grade at John Eaton. The schools technically weren’t

segregated, but there was de facto segregation and there were so few kids

that the fifth and sixth grades were in one classroom.

How did you feel about moving to DC?

I liked being closer to the movie theaters and the National. By

then, I probably would have already preferred to be in New York. There was

a stigma about being a child of divorce—I didn’t know any other kids whose

parents were divorced.

Was theater an escape?

It was a fantasy, a place where I was happy. In some way—and I

don’t mean this in a melodramatic sense—it saved my life. Psychologically,

I think my life would have been very different if I hadn’t found the

theater and if I hadn’t had a mother who, when she saw I was passionate

about it, indulged it as much as she could.

One of the interesting things in your book Ghost Light

is how difficult a character your stepfather, Joel, was but also how

supportive he was of your love for the theater, and how in many ways he

enabled it.

That’s exactly right. The big discovery in writing the book was

Joel. In essence, it was my view and the view of many people in my family

that he killed my mother. My mother died in a car accident on July 4, 21

years ago, when she was a year younger than I am now. He survived the

accident but gradually went mad. I’d been angry at him for most of my

childhood, and I didn’t understand why my mother stayed with him. But in

writing the book, I found myself having a strange kind of gratitude for

him. I learned a lot, really, and I think in the end he upstaged my mother

and everyone else in the book.

Were you interested in politics at that age?

Yes, in an amateur way. Once the Senators moved to Minneapolis,

it became like a sport to follow. I went to the Martin Luther King march

with my mother in 1963 when I was 14, then got involved in politics at

Wilson because I got caught up in home rule and the fight for civil

rights. I always had these two interests—politics and theater. Even at the

Harvard Crimson, I reviewed Sondheim musicals trying out in

Boston while writing editorials about the Vietnam War.

Did you ever consider acting as a career?

There was no real theater at Wilson. The school system was so

poor that often they couldn’t even heat the building.

At Harvard there was one freshman acting seminar. You had to

audition for it, and I did a speech from Philadelphia, Here I

Come! by Brian Friel. To my amazement, I got in. We put on a play,

Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit, and I was utterly bored. I

walked to the Crimson to try out there and never looked

back.

Did performing give you any insight as a critic?

Everything I learned about criticism I learned as a ticket

taker. Some people would come and take tickets and leave at 8:30 or 9, but

I would always stay. I watched shows being rewritten every other night.

You’d see a show that came into Washington a wreck get constantly tinkered

with in the hope of saving it, and you’d see shows that were hits where

the creators just kept trying to improve them. I feel that in my work now

in television and when I was a critic, that was the best education I

got.

After college, you cofounded the Richmond Mercury. How did you

get from there to the New York Times?

I was offered a job at a slick new magazine called New

Times, which had been started by an editor at New York who’d

had a fight with founding editor Clay Felker and left. I worked there as a

junior-junior editor and as a film critic, and that led to me being hired

by the pre-Murdoch New York Post—and the rest of my career,

basically.

Was landing at the New York Times your dream come

true?

It was. It happened completely freakishly. I quit the New

York Post after Rupert Murdoch bought it, as did half the staff, and

I was hired by Time as a movie critic.

Walter Kerr, who’d been a hero of mine as a kid, was nearing

retirement, and the Times didn’t have a successor. They kept

trying to get me to do something over there, maybe editing at Arts &

Leisure, but I had a really good job at Time. Janet Maslin, who’d

been the rock critic at New Times when I was film critic, went to

dinner with Arthur Gelb, who was a great culture editor at the time. He

said to her, “There must be someone who can do theater,” and she said,

“You know that guy you’ve been trying to hire? That’s his real interest.”

I went over to the New York Times in March and became the drama

critic by Labor Day.

What made you go from reviewing theater to writing opinion

pieces?

I started to get bored, which seems to happen to me every 15

years with reviewing. And then my mother was killed, and I wanted to quit

on the spot. There was a month where she lingered in a coma in a trauma

center in Baltimore. I wasn’t really in my right mind. My editor said to

take as much time off as I wanted, so I took off the summer and then came

back to do one more season.

An editor I’d never heard of named Adam Moss—who was then in

his twenties and at Esquire—called me out of the blue and asked

me to write a piece prompted by the AIDS crisis, about the intersection of

AIDS, straight perceptions of homosexuality, gay people, and American

culture.

New York theater was one of the first places where the AIDS

crisis was visible. I didn’t know a lot about it, but Adam convinced me to

do the piece, and it led to me doing some stuff mixing culture and news

for the New Republic. I think that put the idea into my editors’

heads, and then Adam, partly at my instigation, came to the Times

and edited my first columns.

How did Adam Moss—now editor of New York—entice you

away from the Times to that magazine?

He and Arthur Gelb are the two editors who are responsible for

my career. Once I started getting antsy, it was sort of inevitable I’d go

and work with Adam again. One thing about being an op-ed columnist is that

you don’t have an editor, which is considered a perk of the job. It’s fun

at first, but it becomes sort of isolating and boring. I like working with

smart editors, and Adam is the best one I’ve ever worked with.

Tell me about your involvement with the TV show Veep.

I started working at HBO as a sideline 41/2 years ago when I

was still at the Times. My main role there is as a

consultant.

But I always have the option to be involved with the

development of shows, and I got involved with Veep early on. HBO

had been looking for a smart Washington show. When I saw [Veep

writer/director Armando Iannucci’s] film In the Loop at a

screening by happenstance in New York, I said, “This is the

guy.”

It’s been a total blast, and we’re going to do a second season,

which starts shooting in October. All these writers are British, yet they

really get Washington.

That’s the thing that surprised people here—how a team of Brits

can get Washington so right.

They’re political junkies—Armando is a Milton scholar and a

Dickens fanatic, but he spends half the time reading Robert Caro on Lyndon

Johnson and reading the same websites we all do, Politico and all that.

But he’s not romantic about it the way Americans are, so it’s very

different from the Hollywood view of Washington. He just has a feel for

it

And Julia Louis-Dreyfus grew up in Washington like

you.

The first thing she said to me when we met was “Wasn’t your

father Rich’s shoes?” I told my father that, and he loved it. Her mother

and stepfather live in Somerset.

You wrote a controversial New York Times Magazine

article in 2002, “The De Facto Capital,” which compared Washington

unfavorably with New York.

Washington has changed Dramatically since then. You can see,

driving around the city, that it’s changed physically, but the cultural

stuff has also ramped up considerably.

I also quite frankly feel that Obama’s election made a

difference, even though like every other President he starts by saying

“I’m going to be really present in Washington” and then is only ever seen

at Sidwell Friends. DC has historically been a black city that’s treated

as a stepchild by the federal government, and when I was growing up, it

was run by white racist then-Democrats on committees in the House. It’s

been treated like a plantation by Congress. That’s started to change,

although the city still doesn’t have the representation and home rule it

should have.

I think there’s something empowering about having an

African-American in the White House in this city. It also makes the people

outside Washington think of it differently in a way that Kennedy did when

I was a kid.

But it’s still a company town. What I like about New York is

that it’s 20 companies, not one. But I don’t dislike coming here, and I

have family here, so I remain attached to it.

This article appears in the October 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.