It’s midday at Fancy Cakes by Leslie in Bethesda, and half a dozen women line long tables behind the counter, quietly constructing perfectly round, multitiered cakes and carefully applying icing. They go through 36 pounds of butter a day.

Fancy Cakes’ owner, Leslie Poyourow, stuck by butter as an ingredient since opening her shop in the mid-1990s, even as other bakers moved to cheaper partially hydrogenated oils—those that have been artificially solidified to mimic butter but have a longer shelf life. Poyourow prefers the taste of butter and says, “You’re eating real food.”

Poyourow sees another advantage to butter that bakers across the United States might want to heed. When the Montgomery County Council banned partially hydrogenated oils seven years ago, she didn’t need to scramble to find a substitute for her shortening.

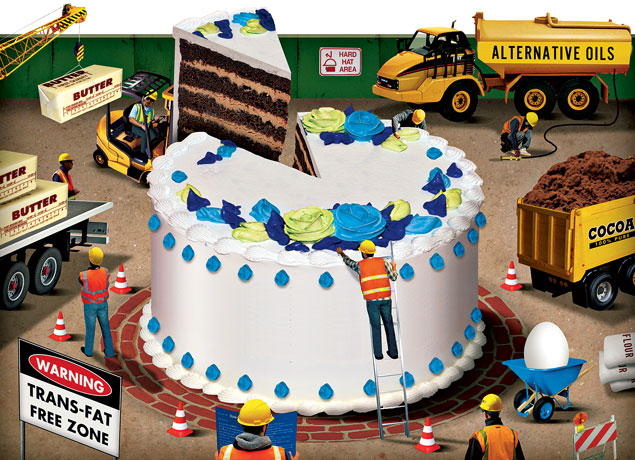

With the Food and Drug Administration on the verge of banning partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs), all food manufacturers may soon be in search of new ingredients. After announcing the proposal in early November, the FDA is set to end its comment period in March. The phaseout of PHOs—also known as trans fats—would outlaw an essential component of some of America’s favorite treats, from sugar cookies to hot dogs. The timeline will depend on feedback the FDA receives from restaurants and food manufacturers, but officials have said they hope to move quickly.

Food producers have been using PHOs since the 1940s to improve taste and texture and to lengthen their products’ shelf life. (PHOs also cost less than animal fats and butter, both of which contain low levels of trans fat but are exempt from the proposed ban.) But in the early 2000s, amid undeniable evidence that linked PHOs to heart disease, New York City, Philadelphia, and a dozen other jurisdictions started a movement to end the use of these fats in establishments that prepare food on-site, from doughnut shops to fine restaurants.

• • •

In Montgomery County, Duchy Trachtenberg was ahead of the curve when she took on PHOs. A longtime resident of North Bethesda, Trachtenberg once had a social-work practice specializing in adolescent addiction. At meetings of the American Public Health Association, where she chaired the alternative-health division, she often heard about links between trans fat and heart disease.

When she ran for a seat on the Montgomery County Council in 2006, she was aware that the council also sat as the Board of Health, giving it the unusual power of making health regulations. Trans fats came up during the campaign, she says, “but it wasn’t part of a political platform.”

On taking office, Trachtenberg moved to introduce the ban. It didn’t take much convincing to get the rest of the council onboard. “It seemed like good health policy, and of course it had happened successfully in New York City,” she says.

And the tide was already turning. Taco Bell, KFC, and other chains had switched, as had Bethesda’s Marriott International hotels and the Silver Diner chain.

Still, convincing the local restaurant community, Trachtenberg knew, would be difficult.

“At the beginning, it was kind of hard because [food supply] companies didn’t have the products,” says Andrea Romero, an employee at the Chicago Bakery in Wheaton. When they did, Silver Diner cofounder Ype Von Hengst says, alternative oils were noticeably more expensive.

At the time, according to Melvin Thompson, senior vice president for the Restaurant Association of Maryland, even federal policy was tilted toward PHOs. The government “encouraged many farmers to plant high-profit corn crops instead of the soybeans that are used to make trans-fat-free oils,” he says. One expert testified to the council that McDonald’s search for a suitable PHO-free frying oil took four years.

Trachtenberg countered with experts spouting statistics about the dangers of trans fats; she hosted a food tasting of trans-fat-free cooking in Rockville. At the public hearings held in late April, Trachtenberg brought in a secret weapon: Jeff Black of the local Black Restaurant Group, which includes the popular Montgomery County eateries Black Market Bistro and Black’s Bar & Kitchen.

Black was drawn to the cause by his son’s diabetes, which had highlighted for him the connection between nutrition and health. At the hearing, televised on the county’s public-access channel, Black—wearing his double-breasted chef’s whites—argued against friends and colleagues on behalf of the bill.

“The core of what I do is provide sustenance,” Black says today. “I wouldn’t serve food to people if I knew it was harming them.”

Against overwhelming scientific evidence and with dwindling economic arguments—alternatives turned out to be “pennies more,” Trachtenberg recalls—the restaurant association dropped its opposition, requesting only “realistic timetables” to make the switch. The measure passed on May 15, 2007, and restaurants were to be trans-fat-free by the following January. Bakers, including chains such as Dunkin’ Donuts, got an extra year to find alternative oils. Even with the grace period, councilman Roger Berliner said on the day of the vote, “doughnuts are in a world of trouble right now.”

• • •

Medically, it’s nearly impossible to evaluate the ban’s effect on Montgomery County residents.

“The benefits may take years to accrue,” says Michael Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, who also testified in favor of the ban six years ago. And with so many factors contributing to heart disease, it’s hard to isolate the impact.

Culturally, however, the Montgomery ban—the first in the US by an individual county—helped make the case that preventive health measures are part of government’s job, a change in mindset whose effects aren’t limited to health. The FDA estimates that, over 20 years, removing trans fat from the national food supply could save—in addition to thousands of lives—$117 billion to $242 billion.

“Core diet is the number-one cause of death and disability in this country,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, a professor at the Harvard School of Public Health. If the US had a “real” public-health system, Mozaffarian says—one whose ability to prevent disease matched its ability to treat it—“we could pretty easily balance the budget.”

Thanks to the momentum generated by the local bans, Jacobson says, the transition to healthier fats will be relatively easy: Trans fat “became essentially a dirty word. That spurred food manufacturers to find substitutes.”

Others aren’t so sure. The FDA would go further than the local bans, eliminating trans fats from popular processed foods that sit for days or even weeks on supermarket shelves—think microwave popcorn (Pop Secret Butter Popcorn contains five grams of trans fat per serving) or Sara Lee New York Style Cheesecake (two grams)—greatly increasing the demand for alternative oils. “On a nationwide scale, supply is going to be an issue,” says Hilary Thesmar, vice president of food-safety programs for the Food Marketing Institute.

Nor is it certain all foods will have cost-effective, and tasty, PHO-free equivalents. “If they could do it easily, it would’ve already been done,” says Janet Collins, president of the Institute of Food Technologists. If the FDA ban goes through, in other words, some of Americans’ most treasured snacks may end up costing more or tasting significantly different.

As the feds catch up to Montgomery County, meanwhile, many local establishments are staying ahead of the trend. Long divested of trans fats, the Silver Diner is in the process of moving to nongenetically modified oils. “It’s a great thing for the general health of the public,” Von Hengst says. “We owe that to them.”

Sarah Scully (sarahelisescully@gmail.com) is a reporter for the Maryland Gazette.

This article appears in the March 2014 issue of Washingtonian.