The Civil War transformed Washington from a sleepy outpost into a federal city, its population nearly doubling between 1860 and 1870. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress

During the two years I spent writing a book about the Civil War, I often felt as if I were living as much in the 19th century as in the 21st. After a long day at the Library of Congress going over old newspapers and yellowing manuscripts, I would emerge from the building and see ghosts everywhere in Washington.

There on the east side of the Capitol were the young soldiers I had just been reading about, playing baseball beneath long-vanished chestnut trees in the first spring of the war. Pennsylvania Avenue, shimmering in the hazy sunlight of a summer afternoon, seemed wreathed in the dust clouds of regiments marching in review. Amid the crowds of commuters at 14th and L streets Northwest, I saw the figure of Walt Whitman, standing on the corner where he used to wait to catch a glimpse of Abraham Lincoln en route to the President’s summer cottage.

Even for less obsessive seekers of lost time, there are lots of places in and around Washington where the Civil War past remains very much present. Unlike many foreign capitals, ours is

not a city where history is obvious and ubiquitous: The grime of centuries doesn’t encrust our gleaming monuments, and looking at the White House, it can be hard to imagine that JFK lived there, let alone Lincoln.

But in this 150th-anniversary year of the start of America’s greatest conflict, here are ten local places—most off the tourist track—where I find the Civil War not just visible but vivid.

1. Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park and National Cemetery

Leesburg

This is no Gettysburg or Antietam. No tour buses disturb the silence. There’s no visitors center or gift shop, nowhere you can buy so much as a postcard. The battlefield is not much to look at—just a broad clearing and a couple of cannons in the woods, near the edge of a quiet suburban neighborhood—and the cemetery contains only a couple of dozen graves.

Yet the tragedy and drama of the Civil War are as palpable as they are at few other places. Here, on October 21, 1861, a force of 1,700 Union soldiers crossed the Potomac from the Maryland side and found themselves in their own version of hell. Their inexperienced commander, Colonel Edward D. Baker—a sitting US senator and a close friend of Lincoln’s—put his troops in an impossible position, with Confederate sharpshooters in front of them and the 90-foot bluff behind.

On a recent Sunday, a friend and I brought the first volume of Shelby Foote’s Civil War trilogy with us and sat on a fallen log at the base of that bluff, reading aloud. The long-ago scene came to life: Yankee soldiers fleeing headlong, scrambling and falling down the steep incline, clambering desperately into the few available boats, only to capsize them in their panic. Here in the muddy river—now placid except for a heron that brushes over the surface—men drowned or were picked off one by one as rebels on the precipice lashed the water with bullets. Bodies drifted miles downstream; some were fished out along what is now the Maine Avenue wharf in DC.

When news of Baker’s death reached Lincoln at the War Department, he walked back to the White House alone, weeping.

Marble headstones stand in a semicircle near the rim of the bluff. All but one—the grave of a Massachusetts private named James Allen—are marked “unknown.”

2. Arlington House

Arlington National Cemetery

Here above the Potomac River stands the proud neoclassical mansion that, in the spring of 1861, was the home of a US Army colonel named Robert E. Lee. Historians still debate what happened in these rooms that April as the Union came apart and Virginia prepared to secede. A recently discovered letter suggests that Lee—who had informally been offered command of the Union troops defending Washington—agonized here over whether to cast his loyalties with his state or his country. Nearly all his close family members opposed secession from the Union.

Lee must have stood on this veranda—which offered, as it still does, a panorama of the city across the river—and contemplated all he was about to leave behind, the familiar capital that was about to become enemy territory. In the end, he sat down alone in his office and penned a letter of resignation from the Army, which a trusted slave delivered to the War Department.

By the end of May, the Lees were gone and federal troops occupied the mansion, setting up a telegraph station in the dining room and digging entrenchments in the formal gardens. Soon they began planting graves: by the dozens, then hundreds, then thousands.

The general would never return to his beloved house. His widow visited once after the war, shortly before her death. Infirm and distraught at the sight of her former home transformed into a cemetery, she didn’t get out of her carriage.

Next: President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home

The cottage on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home where President Lincoln finished the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. Photograph of Lincoln Cottage courtesy of Library of Congress

3. President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home

Rock Creek Church Rd. and Upshur St., NW

On summer evenings, Lincoln left the White House and rode, often alone, on horseback up the Seventh Street Turnpike—now Georgia Avenue—to this stucco cottage on the grounds of the federal institution for disabled veterans. Sitting atop a hill four miles from the presidential mansion, the house caught cooling breezes that relieved the seasonal heat. Even more important, it offered a retreat from the agonizing stress and constant lack of privacy that Lincoln endured in his official residence. Each day, dozens of visitors filled the White House corridors awaiting an audience with the President, demanding federal patronage, offering unsolicited—and often crackbrained—advice, or pleading clemency for a son sentenced to die for desertion. Only at the cottage could he find peace and a place to think. He spent about a quarter of his presidency here.

Lincoln grappled with the most important and difficult decision of his life in this house. Although he had always detested slavery, he had long hesitated to endorse—much less decree—abolition, fearing that it would only deepen the fissures that had split the country. But by July 1862, swayed by political pressures as much as by moral ones, he had begun his first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. An account of that period records the fact that he gave the second draft its finishing touches at the Soldiers’ Home cottage in September, after news came of the Union victory at Antietam.

The cottage and its role in history were almost forgotten for a century and a half. Now under the stewardship of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, it was restored and opened to the public in 2008. This is not a typical house museum—most rooms are austere and almost unfurnished. In one, a table holds a rotating display; at one point it was several 19th-century volumes of Shakespeare, evoking an evening here in August 1863 that Lincoln’s young secretary John Hay described, when the President “read Shakespeare to me, the end of Henry VI and the beginning of Richard III till my heavy eyelids caught his considerate notice and he sent me to bed.”

In a simple bedroom upstairs is a replica of the desk where equally immortal words were penned: “That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free…”

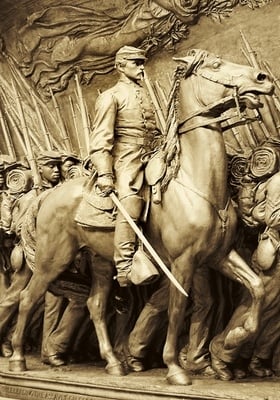

4. Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment

National Gallery of Art West Building

Sixth St. and Constitution Ave., NW

What may be the nation’s greatest work of public sculpture stands not on the Mall but tucked away in the maze of rooms that hold the National Gallery of Art’s collection of 19th-century American art. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s larger-than-life relief, completed in 1897, pays tribute to the men of the 54th Massachusetts and their commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

The 54th—famous in its time and still familiar to many people from the movie Glory—was among the first black units in the Civil War and the first to win renown in battle. In July 1863, the troops staged a bold, doomed assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor. Shaw was killed as he stormed the parapet; nearly half his men ended up dead, wounded, or captured.

Saint-Gaudens labored for 14 years after a group of Bostonians commissioned a monument to Shaw in 1884. The masterpiece that he produced is like no other American war memorial. Instead of placing Shaw alone on horseback or depicting his death in battle, Saint-Gaudens situated him with his troops on the day that they paraded through Boston on their way to the battlefront. Each soldier’s face is distinctive and full of character, based on African-Americans who posed for the sculptor at his studio. Together, they compose an eloquent statement about the idea of belonging, of forming a larger whole—whether a military unit or a free society—while preserving individual liberty and dignity.

The final version of the monument, cast in bronze, was installed on Boston Common alongside the street that the 54th marched down on its way to war. It has inspired poems by Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and others. But DC’s version, although less famous, is more original and more powerful. It is the plaster model, coated in gold and brass leaf, from which the Boston monument was cast. Far more than the metal version, its surfaces convey a sense of the sculptor’s hand at work. For decades it stood deteriorating under an outdoor shelter at Saint-Gaudens’s former house in New Hampshire. It was rescued and restored by the National Gallery more than a decade ago, becoming one of Washington’s most compelling works of art.

Next: Frederick Douglass’s Cedar Hill Home

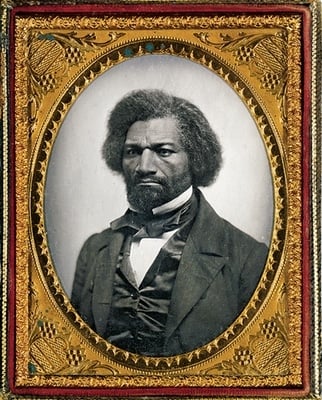

5. Cedar Hill/Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

1411 W St., SE

For decades, Frederick Douglass was the eloquent voice of the nation’s conscience. Born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, he escaped to the North at age 20 and went on to pen three autobiographies along with many articles and speeches. Unlike some other black abolitionists who believed that freed slaves would never find acceptance in America and could only return “home” to Africa, he insisted that they were and must remain Americans. He castigated the nation for its hypocrisy at the same time that he challenged it to fulfill the ideals in the Declaration of Independence.

During the Civil War, Douglass helped recruit black troops and met several times with Lincoln to discuss African-Americans’ service in the military. After the war, he moved to Washington, where he held several government posts, including recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia. Hundreds of the city’s Victorian rowhouses bear Douglass’s signature on their original title documents.

In 1877, he bought Cedar Hill, an antebellum mansion in Anacostia that became a public monument after his death. The Douglass whom visitors encounter here is not the familiar, somewhat rigid icon but the private man—warm and passionate and proud. It’s the opposite of Lincoln’s cottage in the sense that every room is crammed full of his stuff, lovingly saved by his family: photos, books (from children’s poetry to political tracts), and a pair of well-worn shoes in the bedroom that look as if he just stepped out of them.

6. Old Patent Office Building

Eighth and F sts., NW

After the Union defeat at Fredericksburg in 1862, hundreds of wounded men were sent by train and wagon to Washington to be cared for—and in many cases to die. The capital didn’t have the hospitals to accommodate all of them, so the soldiers were laid out on the floors of public buildings, including the Patent Office Building, where they found space among the rows of glass vitrines displaying models of American ingenuity.

One of the civilians who volunteered to nurse these suffering men was a minor government clerk and sometime poet whose brother, a Union lieutenant, had been among the wounded at Fredericksburg. Walt Whitman came almost every night, offering books, candy, or just tender caresses and reassuring words. Two years later, in the same building—now no longer a hospital—he witnessed a different scene: Lincoln’s second inaugural ball. With final Union victory imminent, the crowd grew so exuberant that it upended the buffet tables and trampled the foie gras, roast pheasant, and sponge cake.

The building now houses the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. The two institutions exhibit many powerful works of art related to the Civil War, including paintings by Winslow Homer and Eastman Johnson and original plaster casts of Lincoln’s face and hands.

Five years ago, in the midst of major renovations, workers stripping paint from a window frame found an inscription—initials and the date 1864—scratched by a Civil War soldier, possibly a wounded patient. Protected under a small sheet of Plexiglas, it can be seen near a corner of the third-floor galleries of contemporary art, a modest token of the past among the David Hockneys and Nam June Paiks.

Next: Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office

At Fort Stevens, the only Civil War battle site in DC, President Lincoln came under fire. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress

7. Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office

437½ Seventh St., NW

It was a tale of discovery reminiscent of King Tut’s tomb. In 1997, an official from the General Services Administration was poking around a federally owned building in DC’s Penn Quarter that was slated for demolition. On an upper floor whose rooms had been sealed off for nearly a century, he stumbled upon a historical trove: 19th-century letters, clothing, and a sign reading MISSING SOLDIERS OFFICE. 3RD STORY, ROOM 9, MISS CLARA BARTON.

In this building, Barton—like Whitman, a government clerk inspired to aid the Civil War wounded—established a privately run bureau to track down the fate of missing men. This was essential work in an era when thousands of anonymous corpses were recovered on the battlefield, with no formal system to notify relatives of a loved one’s death. Barton, who would go on to found the American Red Cross, provided information to the families of more than 20,000 men.

The building was saved, and restoration has begun; it will eventually become a museum. (It’s still closed to the public except for occasional special tours; for information, contact the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.) Barton’s rooms—where she also lived—remain a time capsule. The 19th-century wallpaper she installed hangs from the walls in tatters. One door, marked with the number 9, has a narrow mail slot through which letters by the tens of thousands once passed, bearing tidings that reunited families or broke hearts.

8. Walt Whitman Inscription

Dupont Circle Metro,

Connecticut Ave. and Q St., NW

Of all the Civil War monuments in Washington—bronze generals, marble goddesses, even the Lincoln Memorial—none moves me more than the words carved into the granite above the escalators at this exit from the Dupont Circle Metro. They are lines from Whitman’s Civil War poem “The Wound Dresser”:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way

through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with

soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night—some

are so young;

Some suffer so much—I recall the experience

sweet and sad . . .

The inscription, engraved in 2007, was designed to honor not just Whitman but also those who, in a similar spirit, cared for people with AIDS when the disease ravaged the Dupont Circle area in the 1980s and early ’90s. It is, in its minimalist way, a profound work of art. It unites present and past.

Its placement above the escalators suggests both descent into the afterlife and resurrection. Each day, it reminds thousands of self-absorbed commuters to step outside themselves, to make caring for others a duty as routine and quotidian as their office jobs—just as it was for the good gray poet a century and a half ago. Opportunities for heroism, it tells us, do not come only on the battlefield.

Next: The only Civil War battle site in DC

9. Fort Stevens Park

13th and Quackenbos sts., NW

This patch of green space in DC’s Brightwood neighborhood has two claims to fame. It’s the only Civil War battlefield within the District. More significant, it’s the only battlefield where a sitting President of the United States came under enemy fire.

Lincoln’s too-close brush with the war came on July 12, 1864. The Rebel cavalry commander Jubal Early had staged a daring raid on the capital’s outskirts. Though aware that he stood no real chance of capturing the well-defended city, Early decided to assault the Union lines anyhow, to win a victory for Southern morale if nothing else.

The Confederate snipers must have been astonished to see, looming above the earthworks opposite, the silhouette of a lanky, stovepipe-hatted figure familiar from cartoons and lithographs: Lincoln had come out to observe the clash. Several eyewitnesses recorded that he took cover only after the Yankee officer at his side was felled by a rebel bullet; another wrote that a young Union staff captain—who happened to be Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the future Supreme Court justice—shouted, “Get down, you damn fool!”

Today the small park, with its reconstructed segment of fortifications, is hemmed in on every side by modernity: parked cars, a radio tower, and apartment houses from the middle of the last century. The ground is littered with the archaeology of very recent history: Someone sat beside this gunport eating a Big Mac; someone smoked a cigar on the earthwork opposite. But if I hunch down with my volume of Shelby Foote, ignore the sound of rush-hour traffic on 13th Street, and face toward the low green mounds, it could almost be 1864.

See Also:

10. Mary Surratt Boarding House

604 H St., NW

The plain brick dwelling on H Street resembled hundreds of other cheap boarding houses in Civil War–era Washington. But the events that played out secretly here in late 1864 and early 1865 were anything but ordinary. In this building, landlady Mary Surratt hosted John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators as they plotted the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

The English-basement level, which was the dining room and kitchen of the old boarding house, is now a Chinese and Japanese restaurant called Wok and Roll. Nothing of the historic interior remains. The upper floors, which contain apartments off-limits to the public—and to historical researchers, it seems—are apparently much more intact.

The food served by Mrs. Surratt’s latter-day heirs is, I have to confess, only so-so. Still, it’s worth sitting down for a little while over steamed dumplings or egg-drop soup, contemplating the murder of a President and the changes wrought by time.

This article appears in the August 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.