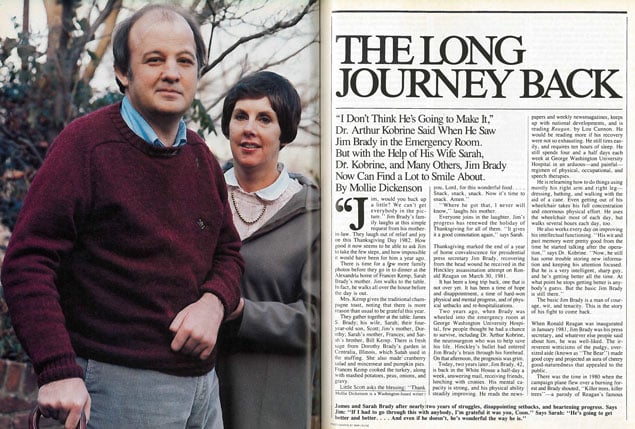

“Jim, would you back up a little? We can’t get everybody in the picture.” Jim Brady’s family laughs at this simple request from his mother-in-law. They laugh out of relief and joy on this Thanksgiving Day 1982. How good it now seems to be able to ask Jim to take the few steps, and how impossible it would have been for him a year ago.

There is time for a few more family photos before they go in to dinner at the Alexandria home of Frances Kemp, Sarah Brady’s mother. Jim walks to the table. In fact, he walks all over the house before the day is out.

Mrs. Kemp gives the traditional champagne toast, noting that there is more reason than usual to be grateful this year.

They gather together at the table: James S. Brady; his wife, Sarah; their four-year-old son, Scott; Jim’s mother, Dorothy; Sarah’s mother, Frances; and Sarah’s brother, Bill Kemp. There is fresh sage from Dorothy Brady’s garden in Centralia, Illinois, which Sat.ah used in the stuffing. She also madel cranberry salad and mincemeat and pumpkin pies. Frances Kemp cooked the turkey, along with mashed potatoes, peas, onions, and gravy.

Little Scott asks the blessing: “Thank

you, Lord, for this wonderful food … Snack, snack, snack. Now it’s time to snack. Amen.”

“Where he got that, I never will know,” laughs his mother.

Everyone joins in the laughter. Jim’s progress has renewed the holiday of Thanksgiving for all of them. “It gives it a good connotation again,” says Sarah.

• • •

Thanksgiving marked the end of a year of home convalescence for presidential press secretary Jim Brady, recovering from the head wound he received in the Hinckley assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan on March 30, 1981.

It has been a long trip back, one that is not over yet. It has been a time of hope and disappointment, a time of hard-won physical and mental progress, and of physical setbacks and re-hospitalizations.

Two years ago, when Brady was wheeled into the emergency room at George Washington University Hospital, few people thought he had a chance to survive, including Dr. Arthur Kobrine, the neurosurgeon who was to help save his life. Hinckley’s bullet had entered Jim Brady’s brain through his forehead. On that afternoon, the prognosis was grim.

Today, two years later, Jim Brady, 42, is back in the White House a half-day a week, answering mail, receiving friends, lunching with cronies. His mental capacity is strong, and his physical ability steadily improving. He reads the newspapers and weekly newsmagazines, keeps up with national developments, and is reading Reagan, by Lou Cannon. He would be reading more if his recovery were not so exhausting. He still tires easily, and requires ten hours of sleep. He still spends four and a half days each week at George Washington University Hospital in an arduous—and painful—regimen of physical, occupational, and speech therapies.

He is relearning how to do things using mostly his right arm and right leg—dressing, bathing, and walking with the aid of a cane. Even getting out of his wheelchair takes his full concentration and enormous physical effort. He uses the wheelchair most of each day, but walks several hours each day, too.

He also works every day on improving his intellectual functioning. “His wit and past memory were pretty good from the time he started talking after the operation,” says Dr. Kobrine. “Now, he still has some trouble storing new information and keeping his attention focused. But he is a very intelligent, sharp guy, and he’s getting better all the time. At what point he stops getting better is anybody’s guess. But the basic Jim Brady is still there.”

The basic Jim Brady is a man of courage, wit, and tenacity. This is the story of his fight to come back.

• • •

When Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in January 1981, Jim Brady was his press secretary, and whatever else people said about him, he was well-liked. The irreverent witticisms of the pudgy , oversized aide (known as “The Bear”) made good copy and projected an aura of cheery good-naturedness that appealed to the public.

There was the time in 1980 when the campaign plane flew over a burning forest and Brady shouted, “Killer trees, killer trees”—a parody of Reagan’s famous claim that trees cause more air pollution than cars or factories.

On the campaign trail, Brady was apt to launch into a Bob and Ray comedy routine or quote a couple of pages of Semi-Tough about the varying charms of women. He was also something of a gourmet, having won the 1971 Chicago Bachelor of the Year Award for his “Stuffed Pork to Stuffed People,” and the Washington, DC, Chili Bull Contest with his “Goat Gap Chili.”

It had been reported that Nancy Reagan wanted a photogenic person for the press-secretary job. To dispel any notion that she thought the round and balding Brady wasn’t good-looking enough, Mrs. Reagan dubbed him “The Y and H” (youngest and handsomest), playing on “The O and W,” a nickname her husband acquired on the day he announced his candidacy in 1979. Senator Jack Kemp introduced Reagan as the “oldest and wisest” candidate running.

Beyond the fun, Brady turned into a highly regarded press secretary.

“Brady was good in the White House,” says Gary Schuster, Washington bureau chief of the Detroit News. “He gave the Reagan people a sense of direction about Washington. Most of the players had no idea how it worked. Brady knew Capitol Hill; Reagan’s people knew what was good for Reagan. The commingling was good for everybody.

“And he was beginning to get into the inner circle. He had insisted on full access to Reagan as a condition, and he did have it. Brady had won over the White House press corps because they knew he had access to Reagan.”

Brady loved his work; he says now the job was “a dream.”

“The three months after Jim’s appointment were wonderful,” says wife Sarah, whom Brady playfully calls “Raccoon.” (“I have dark circles under my eyes and little hands that get the food to my mouth very quickly,” explains Sarah. She, in turn, calls the Bear “Pooh.”)

Despite Jim’s long hours—he started each day at 5:30 AM—the Bradys loved the political and social whirl. “Jim walked in one night and said, ‘Isn’t this the way to live?'” Sarah recalls.

• • •

Rick Ahearn, the President’s lead advance man, thought the first shot was a firecracker. When he heard the second shot, he knew it was gunfire. It was 2:25 PM.

Ahearn, presidential adviser Michael Deaver, press secretary James S. Brady, and the Secret Service detail were with President Reagan as he left the Washington Hilton Hotel that afternoon of March 30, 1981. As they walked toward their limousines, their attention was attracted to questions being shouted by reporters in a cordoned-off area. Deaver motioned to Brady to handle it.

As Brady walked toward the crowd, John Hinckley Jr. fired six times in rapid succession. Brady heard nothing. The first bullet had torn into his forehead. Other bullets hit DC policeman Thomas K. Delahanty and Secret Service agent Timothy J. McCarthy, and, although no one knew it at the time, a ricocheting bullet hit the President.

As the shooting began, Ahearn took a running step toward the President, but one of the shots shattered glass on Reagan’s limousine and sprayed fragments in Ahearn’s face. He fell back for an instant. Secret Service agent Jerry Parr pushed the President into the car, and it took off.

Ahearn ran over to Brady, who was lying face-down on the sidewalk. His legs were kicking and he was moaning. Ahearn put his face down close to Brady’s, and then he saw the wound. He shouted, “Jim, don’t move—we’re going to take care of you. Can you hear me?”

“Yes,” Brady groaned. He tried to get up.

Ahearn tried to stanch the blood with his handkerchief, but it filled quickly. He called for more handkerchiefs. A police pistol lay next to Jim’s head, and the photographers were snapping closeups. Ahearn pushed the gun away.

Suddenly, he became aware of a man in a rugby shirt who shouted that he was “here and now” establishing “triage,” a battlefield term for a procedure that gives highest priority to the seriously wounded with the best chance of survival. “This man gets the first ambulance,” yelled the rugby shirt, indicating Officer Delahanty.

“No!” shouted Ahearn. “This man [Brady] goes first. He has a head wound.” The argument continued and expletives flew until an ambulance medic hurried over and Ahearn ordered him to pick up Brady.

“Holy Christ, you’re right,” the medic said, seeing the wound.

Inside the ambulance, another argument erupted, this time between Ahearn and the ambulance driver. The driver insisted he was taking Brady to Washington Hospital Center, four miles away. Ahearn wanted George Washington University Hospital, less than a mile from the hotel. The driver refused to change direction, and then suddenly admitted he didn’t know the way to Washington Hospital Center. Incredulous at this news, Ahearn, with the backing of a Secret Service agent, prevailed, and the ambulance sped off toward GW. That decision saved Jim Brady’s life.

• • •

The bullet had entered at Brady’s left eyebrow, traversed the tip of the left frontal brain lobe, and plowed into the right frontal lobe, ending in the area above his right ear.

“He would not have survived the trip to Washington Hospital Center,” says Dr. Arthur Kobrine, professor of neurosurgery at GW, who took charge of Brady’s case. “He was getting ready to die when they wheeled him into the emergency room. His brain would have herniated—that is, the swelling would have forced the brain stem [the center of cardiac and pulmonary impulses] through the bottom of the skull, constricting it so it could no longer function.”

But Brady was in the emergency room less than ten minutes after the shooting, and the ER staff began working to stabilize his condition.

Dr. Jeff Jacobson, chief resident in neurosurgery, was lecturing in class when he was called to the ER to examine the President. He ran to the ER, and as soon as he determined that Reagan had suffered no neurological damage, he turned to Brady, who had just been wheeled into the bay next to the President.

Brady was awake and moaning, moving his right arm and right leg—good signs. “Most gunshot cases come in with no neurological functions at all—thanks to the efficacy of the high-velocity weapons on the streets these days,” says Jacobson.

Sodium pentothal was administered so that Judy Johnson, an anesthesiology resident, could intubate Brady. Intubation, a very uncomfortable procedure for a conscious patient, is the inserting of a plastic tube down the windpipe to the lungs. The tubing is attached to a respiratory machine, which does the patient’s breathing for him. Pure oxygen thus was forced into Brady’s lungs, making him hyperventilate, which reduced the carbon dioxide in his blood stream. When his brain received the oxygen, it signaled the heart to slow down, thus reducing blood flow and reducing the pressure within his skull.

Through the venous tube in Brady’s left arm, Dr. Jacobson injected lidocaine, which also reduces intracranial pressure; Decadron, a steroid, which protects the nervous system; mannitol, which rapidly increases the concentration of sugar particles in the blood, further reducing brain pressure (the body reacts to mannitol by trying to add liquid to the blood by drawjng water out of tissues, including the brain); and antibiotics to counteract infection from the wound and the surgery to come.

Dr. Kobrine heard the commotion in the emergency area—his beeper was sounding as well—and he took off toward the ER. The first person he encountered was Dr. Daniel Ruge, the President’s personal physician. With him was Nancy Reagan.

The two men knew each other well. Ruge, a neurosurgeon, had been professor of surgery at Northwestern University when Kobrine took his residency there. (Ruge also had been a partner in practice with Loyal Davis, Nancy Reagan’s stepfather.)

“You’d better get in there,” Ruge said. “Someone has been shot in the head. I think it’s the President’s press secretary.”

In the emergency room, Kobrine came up to the group working on Brady. “Have you taken X-rays yet?” he asked Jacobson.

“No, but they’re on the way.”

By this time, the external swelling caused by the wound was such that Kobrine was unable to open Brady’s eyes.

“His pupils were reacting [to light] when he first came in,” Jacobson told Kobrine, and he was breathing on his own, signs that it was not an irreversible injury.

By now, all the intensive training of the emergency-room staff had come into play. The room was full of noise and confusion, yet in its midst were two islands of tranquility, one around the table holding the President of the United States, the other around James Brady.

Dt. Dennis O’Leary, GW administrator Mike Barch, and the Secret Service began to check the credentials of the people in the ER, and gradually the room began to clear.

Ruge was standing at the foot of Reagan’s table, monitoring the President’s pulse by holding his fingers lightly on an artery in Reagan’s foot. He looked over at Kobrine.

“What do you think about your patient?” Ruge asked.

“It’s a terrible injury,” said Kobrine. “I don’t think he’s going to make it.”

“Well, do what you have to do,” said Ruge.

Within minutes, Brady’s X-rays showed Kobrine the path of the bullet and where the bone and bullet fragments were. No more than fifteen minutes had elapsed since Brady’s arrival. Swiftly, Kobrine and Jacobson wheeled Brady to the CAT-scan room, while the ER staff was making sure that he kept hyperventilating, that his head position was stable, that his heart rate and blood pressure did not rise or drop dangerously. A sophisticated X-ray process, the CAT-scan reveals tissue and blood vessels as well as bone. The scan was yielding valuable information when Kobrine halted the process. He felt he had seen enough. He knew he needed to start operating. But first he had to find Sarah Brady—to tell her what he was going to do.

• • •

Sarah Brady was at home in Arlington that rainy Monday afternoon. The day before, she and Jim had been to the repeat performance of the Gridiron Club’s annual show and had stopped to have dinner afterward at Portofino, a favorite Italian restaurant near their home. She would remember that evening at

Portofino—she and Jim had had their wedding rehearsal dinner there seven and a half years earlier—with special affection.

When it came time to pay the bill, neither of the Bradys had any money. Sarah left Jim there “as hostage” while she ran home for her wallet.

She had the television on the next afternoon, tuned to Channel 9. The program was interrupted by a news bulletin: Shots had been fired at the President, but all indications were that they had missed him. It never occurred to her that Jim might have been there.

The phone rang. Sarah, assuming it was her mother, answered, ”Did you hear that?” But it was her friend, Jan Wolff, who said, “Yes.” Jan was crying.

“Do you want me to take Scott?” Jan asked.

“Why?” asked Sarah.

“Didn’t you hear?” Jan replied. “Jim. Jim has been shot!”

Sarah felt a surge of panic. “I’ve got to hang up and call the White House.” She reached an operator at the White House. “I understand my husband’s been shot. Can you confirm that?”

“No,” came the reply. “Hang up and I’ll call you right back.” Within a minute the operator was back on the line. It was true.

“Is he alive?” asked Sarah.

“Yes.”

“Is he stable?”

“Yes.”

Sarah hung up and called Jim’s secretary, Sally McElroy, to find out what hospital he was in. Sally urged Sarah not to drive; she and assistant press secretary Mark Weinberg would be right out with a White House car.

Crying now, Sarah called to her cleaning lady elsewhere in the house. “Frances, come quick. Jim’s been shot.” Settling young Scott with Frances, Sarah turned to leave, taking another look at the television.

A tape of the shooting was already being aired. She saw her husband lying face-down. “Oh, my poor baby,” she cried.

Sarah, joined by Jan Wolff’s husband, Otto, waited at the curb outside. The wait seemed an eternity. When the car came, it took off fast into the mist. It wasn’t until they were halfway to the hospital that Sarah asked where Jim had been hit. ”I assumed he had been winged in the arm or something.”

“It’s a head wound,” she was told.

“Oh, no, not that,” Sarah said. Everything whirled around.

• • •

Melissa Brady, Jim’s daughter by an earlier marriage, was at college in Colorado when she heard the news. She immediately headed for the Denver airport. On the way, she heard a radio report that Jim had died. Distraught, she called her mother in Chicago, who told her it wasn’t true.

Then she flew to Chicago, where she met Dorothy Brady, Jim’s mother, and Bill Greener, an old friend. Together, they boarded a plane for Washington.

• • •

As the White House car carrying Sarah Brady neared the hospital, it encountered heavy traffic drawn there by the shooting. Sarah couldn’t get near the ER entrance. She jumped out of the car and ran through the front door of GW, where she found Sandy Butcher, head of social services, waiting for her. Together, they ran through the hospital to the ER area.

Kobrine told Sarah that Jim had been shot above the left eye, that the bullet had gone through his brain and lodged in the right hemisphere, that his condition was extremely serious, that they were going to operate, that the operation would take four to six hours, and that it would begin immediately.

“If the operation is a success, your husband will wake up tomorrow with little use of his leg and no use of his left arm. Eventually, he may be able to walk. In fact, he may walk out of this hospital someday. However, I want you to know that he could easily succumb to this operation.”

Sarah looked at him. “You’ve got to save my husband,” she said. “Scott needs his father.”

“I had to look away,” Kobrine said later.

Brady was wheeled into surgery just seconds behind President Reagan. Surrounding the President’s stretcher were Secret Service agents dressed in surgical greens, carrying Israeli Uzi submachine guns. No one yet knew who had fired the shots at the Hilton, and the Secret Service was taking no chances.

Kobrine changed clothes. Jacobson shaved and washed Brady’s head. The entrance wound itself was small, about three quarters of a centimeter, just at the middle of the left eyebrow. There was a raised “abrasion collar” around the opening, and injured brain tissue was oozing through the hole, forced by pressure from inside.

Kobrine asked Dr. Mansour Armaly, professor of ophthalmology, to incise an enormous blood clot over Brady’s left eye. Leaving it until later could have cost Brady his sight in that eye. The two specialists went to work simultaneously. Kobrine elected to do a standard “hicoronal” incision across the top and front of the skull.

“We were in his head within an hour of the shooting,” says Kobrine. It was almost 3:30 PM. As they lifted away his skull, a large blood clot gushed to the surface, releasing pressure on the brain and bringing Brady’s blood pressure down to a normal range.

“We inspected everything,” remembers Jacobson, “trying to determine what was viable tissue and what was not, making every effort to be conservative in what we took out. It is important not to be overaggressive, not to even move areas that we had already adjudged from the CAT-scans to be all right. The brain is a very unforgiving organ.” Probing within the mass of damaged brain tissue, excising blood clots and debris, removing abnormal tissue, cauterizing ruptured blood vessels, the doctors were able to extract the bullet fragments.

The bullet had exploded inside Brady’s head, the scattered pieces rebounding, opening cracks in the front and bottom of his skull. These were later to be the source of serious problems of leakage of air and cerebrospinal fluid. (Authorities found later that Hinckley had used “devastator” bullets that explode upon impact. The only devastator to explode that day was the one that hit Brady.)

Five hours later, they were through. At one point, plastic surgeon Jack Fisher had popped his head into the operating room to say, “Hey, the radio just said your patient is dead.”

“Well,” said Kobrine, “no one has told that to Brady or me.”

• • •

Sarah waited out the operation, gradually regaining her composure. Nancy Reagan, Michael Deaver, and Jim Baker appeared in the room. Mrs. Reagan and Sarah embraced. “I am so scared,” said Sarah.

“So am I,” replied Mrs. Reagan. Only then did Sarah realize the President must have been hit, too. “They’re going to be fine. They’re both strong men,” Sarah told Mrs. Reagan.

Sarah was spared hearing the erroneous report of Jim’s death. Others did hear it, but they managed to keep it from her. At one point, Sandy Butcher, head of social services for the hospital, came in and said, with a smile, “There’s no news; they’re still operating.” Sarah, startled, said, “Why wouldn’t they be? He’s alive, isn’t he?” But millions of Americans had just observed a moment of silence with Dan Rather.

Back at the Brady home, Jan Wolff and little Scott’s godfather, David Cole, sat weeping before the television. “That’s my daddy,” said Scott as Jim’s picture came on. Cole picked him up and took him upstairs.

Sandy offered to order hamburgers. Sarah, now joined by Jim’s mother, his daughter Melissa, and others, said, “No, we couldn’t possibly eat.” But Sandy got the hamburgers anyway, and the waiting group ate them all.

At 8:30 PM, Dr. Kobrine appeared in the waiting room, still in his greens. Sarah could tell by his eyes that it was good news.

“I’m very happy with the operation,” Kobrine began. “I’ve had your husband taken directly to the intensive-care unit, bypassing the recovery room.”

He cautioned that there were still some hurdles, the biggest being brain swelling and infection that would keep Brady in danger over the next three days. “I don’t want you to think that we’re out of the woods, but it looks awfully good.”

Jim Brady had beaten the odds by surviving the first hour of his terrible wound. Only one in ten victims does, according to Kobrine. Time was the saving factor—the fact that so little time elapsed between the shooting and the relief of potentially fatal pressure on the brain stem. Brady was in the emergency room and stabilized within ten to twelve minutes.

Two hours later, at 10:30 PM, Sarah got her first look at her husband. His head was bandaged, and his eyes were swollen shut. He was still intubated. All the equipment around him was frightening to her. But the nurses were thrilled. Brady was coming out of the anesthesia and making noises.

“Way to go, Jim,” they said. “Way to go.”

Sarah took her husband’s hand. “Jim, it’s the Raccoon. We’re all here, don’t be afraid, you’re going to be fine.” She looked at the nurses. “I know he’s going to be fine. He’s squeezing my hand.”

Overnight, Brady began to try to remove the tube from his windpipe, practically flinging a nurse across the bed at one point. “Let’s just say we were able to help him guide the tube out,” says Dr. Jacobson, “but he was determined to remove that thing.” Early in the morning, Sarah returned to Jim’s bedside.

“Jim, can you hear me? Do you know who this is?”

“Raccoon,” he said softly but firmly. Sarah did not leave the hospital until the three days of danger had passed.

• • •

Jim and Sarah Brady grew up 700 miles apart—Jim in Centralia, Illinois, Sarah in Alexandria. What brought them together was their love of politics. “We [her family] lived elections when I was growing up,” says Sarah, now 40. Her father worked for the FBI and later on Capitol Hill as administrative assistant to Walter Norblad and Wendell Wyatt, both congressmen from Oregon.

Sarah graduated from William and Mary College and taught school for four years before taking a job with the Republican Congressional Committee. Jim, meanwhile, was educated at the University of Illinois, ultimately earning a doctorate in public education from Southern Illinois University. After an early three-year marriage that ended in divorce but gave him his daughter Melissa, Brady wgund up in Chicago as vice president of a political advertising firm.

“I had heard of him,” says Sarah, smiling. “I knew he was a very soughtafter bachelor.” They were introduced at a Washington political gathering at the Twin Bridges Marriott in 1970. It was pretty much love at first sight, but they carried on a long-distance romance for three years.

Sarah began to be dissatisfied with the uncertainty, and finally suggested breaking off the relationship: “Jim had been married before, so I knew he wasn’t exactly dying to remarry.” Sarah’s suggestion energized Brady, who flew to Washington and proposed. During the engagement, they bought their Arlington home—an “action-enforcing event,” they call it. They were married in July of 1973.

• • •

By Tuesday afternoon, the day after the shooting, the mood at George Washington University Hospital was jubilant. The President was doing well. Tim McCarthy and Officer Delahanty were out of danger. Jim Brady was surprisingly active. He kept moving his right arm around; to keep him busy, the doctors made a ball out of gauze, which Jim—his eyes still swollen shut—threw repeatedly toward the sound of their voices.

Fortunately, for right-handed people like Brady, the left lobe—the less damaged in Brady’s case—defines intelligence and personality’ and controls the motor functions of the right side of the body. The damage to the right lobe, however, left Brady with no use of his left arm and only limited use of his left leg, just as Dr. Kobrine had predicted.

Occupational therapist Susan Baylls Marino began working with Brady almost immediately, massaging and stretching his limbs, on the right side to preserve muscle tone, and on the left side to reduce flexion—the painful tightening of muscles that occurs when the normal balance between the muscles on either side of the limb is disrupted and one side dominates the other.

Jim’s brain injury reduced his ability to suppress his emotions when he talks. At times his voice may go up in tone, and he may appear to be half laughing, half crying. “Take a breath now, Pooh,” Sarah will say.

By Saturday, Brady was out of intensive care. The following week he was able to sit in a chair to eat his meals. Recovery had begun, but the road ahead was to be full of danger from physical and neurological setbacks. Jim Brady’s struggle was just beginning.

• • •

But it was a strong beginning. Within ten days, he was reading the newspaper and watching television. A squawk box was installed in his room so he could listen in on White House press briefings. He had a special White House telephone line.

The week after the shooting, Jim began meeting with Cathy Wynne, the physical therapist who would help him over the next two years. Wynne had read about Brady’s appointment as press secretary and been impressed that “such a neat guy” had been appointed to such an important position. She already felt that she knew and liked him.

Although he had been lively at times with family and friends, Brady was initially unresponsive with Wynne. She tried without success during the first two weeks simply to get Jim to talk to her. One day, Wynne told Jim that she needed to buy a bottle of wine for a dinner party that night. Brady immediately said, “Get Jordan Cabernet Sauvignon ’78. You can get it at Eagle Wine and Liquor.” “I almost fell off my chair,” says Wynne. They were off and running.

The relationship developed quickly. A few days later, Wynne asked Brady to stick out his tongue. He complied with a cartoon sequence, slapping the back of his head to trigger his tongue out, “pulling” it to the left by tugging at his left ear, to the right via the right ear, tugging at his throat to pop it back in. Wynne was impressed and delighted. “That took a lot of initiative, considering his condition. It let me know there was a lot going on in there.” Wynne thinks “the Secret Service at the hospital helped Jim tremendously. They were a White House connection, and they knew him. They would come into his room and tease him.”

But on April 18 came the first of a series of setbacks. First was a 104-degree fever, a reaction to anti-seizure drugs. The prescription was changed, but four days later Brady became inactive and stopped talking. Kobrine did a CAT-scan and a cranial tap, which showed that air was leaking into the cranium through Jim’s sinuses, and pressure had built up. Sarah watched her husband being wheeled into the operating room for a five-hour craniotomy to repair the holes.

Five days later, spinal fluid was detected leaking from Brady’s nose again. His activity was restricted and his head elevated to reduce the pressure on his brain.

In early May, Sarah awoke suddenly at 4 AM. She called the hospital. “I can’t believe you are calling,” said Jim’s nurse. They had just discovered that Jim was having trouble breathing and suspected a blood clot. Dr. Kobrine and vascular surgeon Hugh Trout did a lung scan and found many small clots.

Once again, Jim was lucky; a large clot could have been fatal. Trout operated, installing a permanent plastic-mesh “umbrella” in Jim’s vena cava (the large vein that drains the legs and lower trunk) to catch and strain further clots.

This was to be the pattern of the next two years: steady, gradual improvement, small victories tempered by discouraging setbacks. “If I ever need to get my act together, I call Kobrine,” Sarah says. “He feels that Jim can return to an intellectual and meaningful job. He told me from the beginning that the road would be generally up, but with ups and downs along the way.”

“The recovery of brain-injury patients,” says Dr. Kobrine, “depends on three things: how much viable tissue is left; how adaptable the system is in taking over functions previously controlled by now-missing brain tissue; and how willing the patient is to work. Jim shows tremendous dedication. I admire the hell out of him.”

• • •

On April 25, Sarah attended the annual White House Correspondents Dinner. There was a moving tribute to Jim and a standing ovation for Sarah.

Many newsmen knew Brady well from the campaign, and others knew him from his six prior years in public relations: first on the Hill, then at HUD, the Pentagon, the Office of Management and Budget, the 1976 presidential campaign, and back on the Hill with Senator William Roth, Republican of Delaware.

In 1979, Brady was tapped to handle press for John Connally’s run for the presidency. When Connally dropped out of the race, the Bradys took a long weekend at one of their favorite spots—the Tidewater Inn—on the Maryland shore. It was there that Ed Meese called and asked him to come aboard the Reagan campaign.

Brady flew to California for his first interview with Reagan. “Jim just fell in love with Reagan,” says Sarah. Adds Jim’s friend Gary Schuster, “They had a lot in common—both Irish, both with a good sense of humor, both from Illinois. The groundwork was there for a good relationship.”

On the night he was named press secretary, Jim and Sarah had uncorked a bottle of champagne, having been alerted to expect the phone call. When Reagan called, Jim said, “We’re already celebrating with champagne, Mr. President.”

• • •

Six weeks after the shooting, the first set of crises was over. With a lot of help, Brady was now standing and walking a few steps each day. His room was filling up with teddy bears from all over the country. On May 12, a truck pulled up near the hospital with a huge sign on its side: GET WELL JIM BRADY. Excited, Brady moved to the window with the help of Cathy Wynne and Dr. Kobrine and stood there for several minutes—the longest he had stood yet.

A week later, Jim left his hospital room for the first time. A Secret Service agent and a nurse took him downstairs in a wheelchair for physical therapy. The whole therapy unit was there to greet him, and he talked to people in the halls all the way down and back.

On May 26, another setback. Jim contracted pneumonia, which was successfully treated with antibiotics. In five days, he was well enough to celebrate his recovery with a pizza party.

In June, Brady was hard at work on his physical therapy. He began using the parallel bars, working on standing and balance. To improve his dexterity, he practiced passing a ball back and forth with Secret Service agents.

On July 4, Jim got a taste of freedom. He left the hospital for the first time to attend the White House Independence Day celebration. Later in the month, he and Sarah ventured out again, this time to dinner at the home of their friends Sue and Bob Dahlgren, to celebrate a double wedding anniversary, the Bradys’ eighth and the Dahlgrens’ fifteenth.

Despite his progress, Jim still experienced cerebrospinal fluid leaks. On August 3, he suffered a grand-mal seizure. After heavy sedation, the seizure lightened, but heavier fluid leaks began. A neurologist told Sarah that the seizure may have been caused by brain activity; some neural pathways may have been reconnecting in new ways. But it was clear that more repair work was needed.

On August 20, Kobrine and Dr. Norman Barr, an ear, nose, and throat surgeon, operated for three and a half hours to seal the holes between Brady’s nose and the sinus cavity through which the fluid was leaking.

Despite the problems, it was a good summer. “It was almost fun,” says Sarah. “We became very close to the hospital staff, and all summer restaurant owners were bringing in wonderful food.” Dominique sent hors d’oeuvres for happy hour every Friday night. Germaine sent one delicious meal after another. Mel Krupin sent matzo-ball soup; Mr. Kim of the Sorabol sent Korean food; Scott’s sent barbecue; the Madison Hotel sent Mexican food. Jim Lynn, Washington lawyer and former Secretary of HUD, sent dinner from Jean-Pierre one night, served by a waiter in black tie. Senator and Mrs. Robert Dole sent a champagne-and-candlelight catered dinner.

Jim Brady’s love affair with food had begun early. Even as a teenage Eagle Scout, he told writer Marian Burros, “While everyone else was out trying to climb a mountain, my group was back in camp trying to cook beef Wellington in a reflector oven.”

Brady loves to cook, although his cooking efforts these days still are limited to occupational-therapy class, where he whips up items like his famous Goat Gap Chili, and shares it with hospital staff and doctors. “It knocks your socks off,” claims Brady.

Occupational therapi’St Susan Marino and Brady work to make him dress and bathe himself. Marino also works on his upper body and arms, making him stretch and reach. “I call it Lucy and the Football Time,” says Brady. Marino says that Jim’s left arm has quite a bit of movement, but the muscles are very tight. “It ain’t dead yet,” says Brady.

• • •

On Labor Day, Jim Brady went home for the first time for a day’s visit. It started out as a joyous day, with WELCOME HOME signs all over the neighborhood. As Jim came in the (front door, however, the first thing Sarah noticed was that spinal fluid was leaking from his nose. “It was the worst moment I have had from the beginning of this whole thing,” says Sarah.

Back at the hospital, Dr. Kobrine decided to stop the leaking “come hell or high water” by cauterizing the sinus passages through Jim’s nostril instead of exposing him to yet another craniotomy. The procedure worked.

“It was just a genius move,” says Sarah. “I’ve never met anybody who had such dedication to his patient.”

The admiration was mutual. Kobnne and his wife, Cindy, became intimate friends of the Bradys as they struggled together along the road to recovery. “Sarah is an extraordinary person,” says Kobrine. “I have dealt with many, many families in similar circumstances, and I’m telling you she is a strong-willed, tough-minded person who has faced every crisis. She does what needs to be done, time after time.”

Sarah feels she hasn’t done any more than any other wife would have done. “I guess I have a certain amount of strength to handle the big problems of life. It’s the little ones that get me down, like when the washing machine breaks down.

“I just try not to compare our lives now with before. First, you’re grateful for life itself—that Jim survived—and then you’re thankful for all the small signs of progress. For a long time I didn’t believe that Jim’s left arm might be disabled, but little by little I have been able to accept it. On the other hand, I feel confident that Jim will regain a lot of his former ability. The way he thinks is no different; his judgment, his reactions to events are the same as they ever were.

“I was luckier than a lot of people who have lived through this sort of thing. I received so much support from family, old friends and new friends, from the press, and from people around the country. We weren’t really a close neighborhood before, but since this happened we’ve had a lot of gatherings.

“Sometimes I worry that our roles are a little bit reversed,” Sarah says, “and that Jim may resent that.” But Brady makes it clear that, far from resenting it, he knows he couldn’t make it without her. “He says, ‘If I had to go through this with anybody, I’m grateful it was you, Coon.’

“And my mother, I can’t say enough about my mother. For months, she took care of Scott. And my brother transferred from the West Coast to be here for us. Some of the press, too, turned out to be among our staunchest friends. President and Mrs. Reagan have been so nice to us on a personal basis, always remembering to call on special occasions.”

• • •

October was a good month. Jim’s left leg became strong enough to permit him to transfer from a long-legged to a shortlegged brace, giving him more mobility. He also was well enough to begin classes in speech pathology. Until then, Brady had been too drained by his physical healing, high drug levels, and the continuing problem of intracranial pressure. Dr. Kobrine says, “Jim’s humor, his body of knowledge, his intelligence, and his skills were all there. What was impaired was the ability to control and use those skills.”

With speech pathologist Arlene Arrigan Pietranton, Brady began going over the newspaper and answering questions about what he had read. This effort was designed to improve his short-term memory and help him approach his reading in an orderly fashion.

On November 9, seven months after the assassination attempt, Brady returned for a visit to the White House press office. He was greeted by the cheers and applause of reporters and staff members, and by President Reagan himself.

“Jim, we’re all waiting for the day you’re back for good,” said Mr. Reagan.

“I am, too, Mr. President,” Jim replied.

Helen Thomas of the AP said, “We miss you, Jim.”

“I miss you, too,” he said, and, after a well-timed pause: “I miss most of you.”

Brady spotted Sam Donaldson, ABC White House correspondent, who had been outside with a crew to photograph his arrival. “We tried to run over Sam in the street,” Jim joked.

As an attendant pushed Brady’s wheelchair toward the exit, Jim called behind him, “I’ll come back.”

• • •

On November 23, 1981, Jim Brady went home to stay, in time for Thanksgiving.

On the big day, good friend Bob Dahlgren was in the fifth-floor room at the hospital to help Jim leave.

“You weren’t able to walk in on your own steam, but, by God, you should walk out of here,” Dahlgren told him.

Brady immediately stood up, ready to walk the quarter mile to the door. “Not yet, dummy,” said Dahlgren. “The guy was actually ready to try it.”

Downstairs, Jim Brady walked slowly the few steps to the car, right arm on a metal crutch, left arm guided by Cathy Wynne. Sarah was at his side.

At home, the Bradys uncorked a bottle of champagne. Coming home meant the reuniting of the Brady family—Sarah, Scott (then three), and Jim’s nineteen-year-old daughter, Melissa. By then the household included two nurses, Linda Day and Emmy Fox, relieved at times by Rita Nichols, who worked in shifts helping Jim dress, bathe, and get around, and accompanying him to the hospital for therapy. “They’re part of the family now,” says Sarah.

Brady began to enjoy life and his children again. Scott, who was two when the shooting occurred, started getting used to having his father around again. They resumed the ritual of having Jim read to him, both of them settled in Jim’s lounge chair in the family room; the area is known as “Pooh Corner.” Scott loves to climb all over his father as he stretches out in his chair. “Help, I’ve had a Scott attack,” Jim says.

• • •

Through the New Year and early spring, Jim made steady progress. The Bradys went out to restaurants with friends and became regulars at the Birchmere for bluegrass music and hamburgers. At 10:30 AM four days a week, a White House van picked Jim up at home and delivered him to George Washington University Hospital for his day of therapX two hours of physical therapy (“PT—stands for pain and torture,” cracks Brady); one hour of speech pathology and another of occupational therapy (“obvious torture”).

In physical therapy, Jim and Cathy Wynne developed an easy, bantering relationship. Wynne kept pushing Brady to expand his limits. “I’m crippled, you know, and you’ve got to be nice to me,” Jim teased. “Keep working,” Wynne retorted. The regimen was exhausting, but the results encouraging.

Then on March 29, one day before the first anniversary of the shooting, Brady suffered another setback. Painful blood clots had formed in his leg, he developed a lung infection that interfered with his breathing, and a digestive disorder made him nauseated. Dr. Kobrine brought internist George Economos into the case to oversee Brady’s general health, and to monitor and coordinate the many drugs he was taking. He was readmitted to GW, where he was to spend four weeks.

• • •

“Jim had thought everything bad was behind him, and here he almost had to go through the same thing again,” says Dr. Kobrine. “He must have asked himself, ‘Is it worth it?'”

It was a bad time for the Bradys, and it also coincided with the start of the Hinckley trial in late April of 1982. Publicly, Jim was his wisecracking self. “I’m glad he wasn’t a better shot,” he told a reporter. But Gary Schuster recalls watching television with Jim one night when news of the trial came on. “Jim looked over at me, and I could see tears in his eyes. He said nothing.”

Later during the trial, Jim said of Hinckley, “I have no feeling toward him one way or the other, except for pity.” A year earlier, the Bradys received a telegram from John Hinckley’s parents after news accounts appeared of the Bradys attending the July 4 party at the White House. “It said something to the effect that ‘We were thrilled to see you out—we pray for you every day,’ ” Sarah recalls. “I must say it took me aback, but I was pleased to see they care. I feel sorry for them. As a mother I can empathize with their feelings.”

When the verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity was handed down on June 21, the Bradys chose not to comment. Their attorneys later filed a $46 million civil suit against Hinckley and followed it with a $100 million suit against the companies that had manufactured and assembled the handgun Hinckley used.

The combination of physical setbacks and the trial took its toll on Brady. “He lost strength and weight,” says Dr. Kobrine. “He was down in the dumps. He saw the possibility that this guy who doesn’t care about anybody might go free.”

• • •

Jim Brady did bounce back. By April 24, he was well enough to appear at the Washington Correspondents Dinner. And he threw out the first pitch at the “Oldtimers” baseball game in RFK Stadium.

Another flare-up of phlebitis, eight days after the Hinckley verdict was announced, was quickly detected and treated. While he was in the hospital, however, doctors performed a permanent surgical procedure, which acts to siphon off excess cerebral fluid that had been exerting pressure on Jim’s brain. The result was dramatic. Brady became more responsive, more full of jokes, more talkative than before.

By early August, Sarah Brady could say to a caller, “We’re celebrating here today. Jim walked 125 feet by himself!” In mid-August there was a temporary downturn—a fractured vertebra in the lower back, triggered by the blood-thinning drugs Brady had been taking to control clotting. The drugs tended to make his bones porous and susceptible to breaking or, in this case, compressing.

Rest helped ease his discomfort, but the problem would trouble him for months. Nevertheless, in a week he was back at “pain and torture” therapy and all the rest. Jim’s new ability to walk alone made it easier to get out. The Bradys went back to the Sorabol for Korean food. Dining there one night, Sarah asked the chef whether a particular dish was made with peanut oil. Quipped Brady, “Where have you been, Coon? Peanut oil was the last administration.”

They went to Wolf Trap to see The Sound of Music, and Jim got a long standing ovation from the crowd as he was wheeled to his seat. They went by train to Chicago, where Jim was greeted by 300 well-wishers from his home state. There, he threw out the first ball at Wrigley Field when his beloved Cubs played the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In October, they spent an evening at Charlie’s Georgetown listening to nightclub singer Sylvia Syms. Syms approached Jim’s table and sang to him:

From this moment on,

You and I, babe.

We’II be ridin’ high, babe.

Every care is gone.

From this moment on. …

On November 20, 1982, Jim Brady returned to his office at the White House. He retains the title of press secretary. He spends half a day a week there now, and, although he is not officially active in White House affairs, he sits in on the planning session for that day’s press briefing.

His political instincts are sharp. Asked for his reaction to Reagan’s impromptu press conferences in January and February, Brady said, “I think it’s good for him. When your strong suit is communication, you oughta be there communicating.”

More than anything else, his return to the White House symbolizes the degree to which Jim Brady, with the help of a lot of other people, has recovered.

• • •

The prognosis is that Brady will continue to improve. What is unknown is how long his condition will continue to improve, at what point his progress will “plateau.” Dr. Kobrine says, “Improvements in a patient’s condition might continue for as long as five years. The greatest indicator is, if he keeps getting better, then he’s likely to keep getting even better.”

Speech pathologist Arlene Pietranton says, “As long as there are changes, then we know the brain is adapting and reconnecting in new ways.”

The medical problems that plagued him for so long seem to have abated, although he still requires a variety of drugs to control pain, clotting, and seizyres. The “wailing”—the tendency for his voice to rise—is coming under control. “He’s going to get rid of that,” says Dr. Trout. “He’s going to be able to talk without emotion.”

“I have seen him make dramatic improvement,” says Pietranton, “and there really hasn’t been anything to make me feel he is plateauing yet. He is quick-witted, he has a high level of abstraction and integrated thinking. My goal right now is to increase his intellectual endurance, to increase the speed at which he accomplishes tasks, and to increase the thoroughness of responses.”

Brady, listening, says, “Their goal is to see that you never speak again and so can’t testify against them.”

“Half of what we do in here is sparring with each other,” laughs Arlene.

Brady still lives with daily pain, mainly from two sources: the joint in his right shoulder, which takes a lot of stress from his cane; and muscles on the left side, which stay flexed involuntarily due to his inability to move or control them fully.

Cathy Wynne, the peysical therapist, notes that Brady “spends a tremendous amount of time just standing to correct this flexion. It has been a rocky course, but right now he’s at his highest level ever. Going back to the White House helped- he’s happier and more alert these days.”

Lately Jim has been trying to “walk in” when he goes to public places. At a surprise birthday party for Bob Dahlgren at the Class Reunion recently, Dahlgren says he looked up and “I saw Brady walking in. I thought it was a mirage.”

At the Washingtonians of the Year awards dinner in January, Brady wasn’t wearing his leg brace, and when he tried to stand for his award, he could not. “I don’t get around as well as I used to,” he said. “I’m not Gale Sayers anymore.”

Cracks aside, the day-to-day routine others take for granted is not easy for Brady.

Says vascular surgeon Hugh Trout, “Jim works as hard as any of the rest of us all day. A man of 185 pounds who has one good leg and arm—everything he does is exhausting, and to walk takes total concentration. Instead of [traveling with the President], he has courageously tackled the task of learning how to dress himself with one arm. But he sees the rewards ahead—walking, mobility, selfrespect.”

Will he someday be well enough to resume as press secretary at the White House? Brady describes his own goal: to return to the White House as a communications adviser, and “after that to be an executive in a large public-relations firm.”

Says Dr. Trout, “I think he can do it. I think we are all going to be surprised by Jim Brady.”

And what does Sarah Brady think?

“He’s going to get better and better …. And even if he doesn’t, I don’t care. He’s wonderful the way he is.”

This article appears in the March 1983 issue of Washingtonian.