When Earl Hodnett got a call about a black bear in McLean, the wildlife biologist wasn’t surprised. It was summertime, when young male black bears, banished from their mothers’ dens, are out looking for new territory and a few find their way to the Washington suburbs by way of the Potomac River. Young black bears, usually 90 to 100 pounds, might travel 20 miles in a day. And they’re good swimmers.

The bear in McLean was spotted in a neighborhood of brick Colonials, so Hodnett asked residents to bring in their bird feeders and keep garbage cans inside. One family was scared and didn’t want to leave the house. Another family refused to bring in anything from the yard; they wanted the bear to come back.

“They were from England,” says Hodnett, who handled animal sightings for the Fairfax County police. “They thought this was the coolest thing.”

The bear moved on, as Hodnett knew it would. “Unless you have the only bird feeder in town or you live next to a landfill, you will probably never see that bear again,” he says. “There’s plenty of food out there. From the bear’s point of view, it’s a huge buffet.”

In the past several years, black bears have been spotted everywhere from Arlington to Germantown. A bear destroyed a trampoline in Great Falls while trying to reach a cherry tree; another hid in a tree near Leesburg. Nurses at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville saw a bear run through a parking lot.

“Having a bear in an urban area is not a threat to the public—it’s a threat to the bear,” says Hodnett. “That bear’s going to get hit by a car if he stays here long enough.”

Coyotes, the area’s top mammalian predator, have made appearances in Rock Creek Park and nearby neighborhoods. Red foxes, once nocturnal, are getting comfortable in the suburbs. “You can drive through probably anywhere around the Beltway and see a red fox lying in somebody’s yard like it’s the family collie,” says Hodnett.

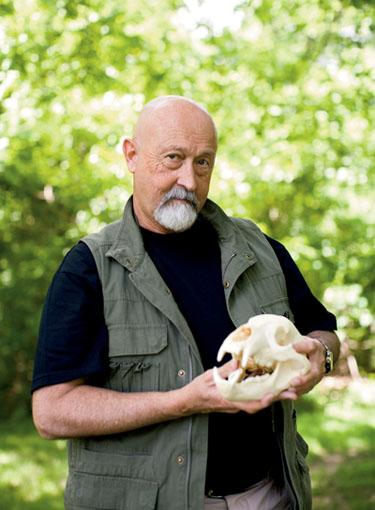

Before joining the United States Department of Agriculture in February—where he works on firearms-and-explosives safety issues for Wildlife Services—Hodnett spent more than a decade fielding calls from area residents who’d spotted something or thought they had. A cougar in Tysons Corner. Deer dining on garden plants. A snake by a pool.

The 61-year-old Alexandria native started his career as a park ranger before becoming chief naturalist for the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority in 1973.

“My house was in the middle of 95 acres in Arlington,” says Hodnett, who now lives in Clifton. “The public still has this concept that wild animals live somewhere else—that’s why it’s such a shock to them when something’s in their yard. They don’t realize those animals are around us every day and every night.”

When did you become interested in wildlife?

My family had a motel on Route 1, south of Alexandria. The motel was close to the highway, but the back end was all natural fields. My dad raised game birds as a hobby—pheasants, quail, domestic and wild turkeys, Canada geese, mallard ducks, homing pigeons. I had a room that was always full of aquariums. I would catch snakes, turtles, and frogs and keep them for a while. When I got a little older, I used Fort Belvoir, the army base, as my extended playground—it had streams and ponds.

You were allowed on Fort Belvoir?

That’s the difference between today and then. When I was growing up, I would leave in the morning and go play down at the creek or wander through the woods and be back at suppertime. Nobody worried about you. I knew every square inch of our property. I’d climbed every tree.

Kids today rarely climb trees—and I don’t mean just the first couple of limbs; I mean up there at the top competing with the squirrels. People are almost totally removed from the natural world—what they know of wildlife and nature is what they see on TV. If they do get out, they’re walking a trail. They don’t go off the trail.

People don’t look up. There’s all kinds of stuff flying over us. I see bald eagles every two or three days. The other day, I was driving and saw something I’ve never seen—a pileated woodpecker, which is about the size of a crow, being pursued by a ruby-throated hummingbird.

What else has changed about wildlife since you were a kid?

Back then, rabbits were everywhere. If there was a brush pile in the woods, you could bet someone $20 that if you stomped on it, a rabbit was going to run out. I remember sitting on the porch with my dad, and he could whistle like a quail—he would call and we’d see them come flying toward us. I don’t remember the last time I saw a quail around here.

What would people be surprised to know about wildlife in Washington?

What would surprise them is the quantity and variety of wildlife that live where they live. At some of the classes I’ve taught, I usually have a nocturnal requirement. I make them spend an hour sitting in the woods by themselves, up against a tree. The sounds you hear are completely different than what you hear during the day.

Are we seeing more bears, coyotes, foxes, and other wildlife here than we did ten years ago?

All of those sightings have increased—in most cases, probably doubled.

Why did the Fairfax police need a wildlife biologist?

Fairfax County was grappling with the overabundance of deer. A librarian was killed driving to work one morning in McLean in 1997. They established the position of wildlife biologist to design a deer-management program.

Did the deer problem get better?

I would categorize it as very bad then and very bad now. What we were able to do is keep a lid on it, mostly with sharpshooting and managed hunts. Unfortunately, many plants that people find attractive are viewed as candy by deer.

These overpopulations bring significant, probably irreversible damage to the environment. The deer have removed ground-dwelling plants from this area. Even if we got rid of all the deer today, the deer have kept those plants from emerging for so many years now that the seed bank has lived out its shelf life.

All the animals that depend upon that strata of the forest for food, for cover—all that’s gone. There’s a growing list of forest-dwelling birds whose numbers are on the decline. It’s not just that we have an animal with charisma that everybody likes because of its big brown eyes. It’s a big problem.

There aren’t future generations of the forest. If it’s an acorn trying to sprout, the deer eats the whole thing. When the trees we have die, it’ll all be soccer fields.

How can deer live so close to us?

They’ve adapted. There’s a misconception that we’ve destroyed their habitat and pushed them into smaller areas and that’s why we’re seeing so many. A lot of habitats have been destroyed, but the conversion of forest into suburban property produces better deer habitat. We’ve introduced lawns, azaleas, vegetable gardens, flowers. It couldn’t get any better for deer.

Some landowners deal with it by excluding wildlife from their yard. I’m guilty of that—I fenced off my back yard because of the water gardens I’ve got.

At the same time, you’ve just about removed mortality out of the equation. In a rural area, you might still have predators, you might have more hunting. A deer living in the metro area is probably going to die by automobile collision.

I live in Clifton. There are a lot of two-lane, windy roads. It’s not unusual to see a tree alongside the road that’s been hit by a car, and from time to time there are fatalities that have no obvious explanation. I can’t help but believe that the majority are deer-related. The drivers swerve to miss a deer, hit a tree, and the deer runs away. There’s no evidence.

What kind of calls did you get when you were handing wildlife sightings?

In 1998, we got a call that someone had seen a cougar at an office building in the Tysons area. A maintenance person walked out to the Dumpster at night, and there was this big cat in the parking lot. I looked through the woods for tracks and found none, but I didn’t expect to find any. Cats don’t like to step in mud, so they’ll walk around it. They don’t tend to leave a lot of tracks.

I set up infrared-activated cameras. The local news picked up the story. I’d estimate that for six months I did nothing but investigate cougar sightings. Or people hearing cougars, which is very unlikely—cougars don’t vocalize very much.

Many of the people were hearing red foxes. It got to the point where I made a recording of a red fox barking and kept that next to the phone. I’d get a call: “We heard the cougar last night.” I would say, “Did it sound like this?”

If there was a cougar, with all the deer we have and all the joggers and dog walkers, you would think somebody would have come across a deer killed by a cougar. They kill in a distinct way. They cache their kill—they’ll cover it up with leaves and sticks, and nothing else around here does that. I waited for that call where somebody found that. It never happened.

Wasn’t it crazy to think there might be a cougar in Fairfax County?

Not at all. They’ve had suspected cougar sightings in Montgomery County. It’s bordering on outlandish that it would be a wild cougar—that’s most likely extinct. Because the sightings seem to be clustered, it seems more likely that it’s somebody’s pet cougar that gets out, runs around, generates a lot of phone calls, and goes back home. Some drug dealers keep large cats as guard animals instead of a pit bull.

Wouldn’t a cougar be a threat to the public?

Not if it’s a domestic cougar, because they’ve grown up around people and dogs. I talked to somebody who raises cougars—she said you can take a young cougar and raise it like a dog and it will be as tame as can be. But if that cat sees a deer, you see it tense up.

When you get something like that, it becomes an issue of giving the public the information they need and putting them at ease. Bears fall into the same category. In Fairfax, our policy was if that bear was headed south or west, we would let it go; if it was headed east, that meant it was headed into more traffic crossings. Depending on how fast the car’s going, it’s probably going to result in the death of the bear.

We wouldn’t let a bear get east of Route 123. If he got close, we’d dart him and the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries would take him for a ride to George Washington National Forest and turn him loose.

Could you have seen a black bear in Rockville or McLean 20 years ago?

It happened infrequently. The areas they’re typically found in is expanding. Bears have been found in virtually every county in Virginia except one.

When I was working for the park authority, I had a group of kids there and I showed them slides of animal tracks. Then I took them all to Donaldson Run, a creek that ran through a park in Arlington, and started finding good raccoon tracks in the mud. One of the kids comes running up and says, “Johnny found a bear track.” I said, “I don’t think so. It’s probably just a big dog.” He said, “No—it looks just like the slide you showed.”

I assured the kid it was a dog track. The kid leaves, my wife and I are going to the grocery store on Spout Run Parkway, and we come up to a stoplight with two police cars in the intersection. A helicopter goes over us at treetop level. I get home, and I’m watching the news. They’ve got footage of this bear they’ve been chasing through Arlington. I felt so bad that I’d told that kid he was wrong.

What should you do if you see a bear?

Most people are going to see it out the window of their house. Take some photos. I recommend they stay in their house and let it wander off, but call animal control or a non-emergency police number and report it. If you happen to be walking in a park on a trail and see a bear? Just stand still. Let it move on by. Enjoy the moment because it’s not going to last very long.

There’s really no circumstance in which you should move toward the bear. If that bear knows you’re there, it’ll try to put as much distance between the two of you as it can, as quickly as it can. You shouldn’t do anything to make it feel cornered.

How are the bears getting here?

Bears in Fairfax and Montgomery counties usually come down the Potomac River corridor because there’s a good strip of natural habitat along the river. They’re going to follow that down, hit some major tributary—a big creek—and follow that. The river is not a barrier to most wildlife—we’ve had three deer killed in Fairfax County, two by automobiles, that had ear tags that were put on in Gaithersburg.

Bears can travel all the way through either one of those counties and never see a person if they travel at night. They wouldn’t have to cross a road. They can go through culverts and get everywhere they want to go. It’s like a Metro system for bears.

How often were you seeing bears?

We probably had a bear to deal with—because it was going to get hit—two or three times a year. But there’d be four or five other sightings. When a bear is moving, you can plot it on a map by the phone calls.

We had a bear sighting in Reston, then another in Reston, then it was in the Oakton/Vienna area, moving east. The frequency of calls, and the urgency, kept escalating.

The bear was cornered in a small wooded lot just short of Route 123, darted, and was brought out on a stretcher. There was a daycare center right there, and the kids were plastered against the windows watching. They probably didn’t have recess for weeks.

What brings bears out into residential neighborhoods?

They’re drawn out in search of food. Countless people put dinner scraps out in the back yard so they can see a fox or an opossum.

Two years ago, there was a bear next to a guardrail along I-95 in Prince William County. A state trooper found a motorist stopped along the shoulder, pitching food to the bear. Officers attempted to herd the bear away from the interstate, but when the bear began to go toward rush-hour traffic, they were forced to shoot it.

Another big problem on the horizon will be coyotes—when they begin to associate people with food. Every community has at least one person who’s feeding raccoons, foxes, deer, you name it. Coyotes pick up on that. A coyote’s not going to come up on your deck and eat the cat food you’ve put out for raccoons, but he will hang in the woods, figure out where the approach lanes are, wait for the animals coming to that food, and pick them off. He’s smart.

At some point, he realizes that a person’s putting food out every day, so maybe all people carry food. The next day, he’s out in the woods and a jogger comes down the trail. The coyote is hungry and thinks, if I just nip that jogger, he’ll drop his food.

Or they’ll chase somebody on a bicycle for the same reason. They start testing.

Are there many coyotes in Washington?

You can assume they’re everywhere, but they’re nocturnal for the most part. Coyotes are relatively new here, but we’ve got many years of coyote experience in the western states, and you need only look to them to see what’s coming.

The coyotes come into an area, and nobody really knows they’re around because they don’t want to be seen. They get comfortable. Their numbers build. They get introduced to a human food source, so they begin to shift from night to day and night, and eventually they end up boldly walking down streets in the middle of the day and through people’s yards. That’s the way it is in many places in California.

An Eastern coyote can be 50 pounds. There’s nothing controlling coyotes. Coyotes are smart enough that they don’t get hit by automobiles as often as other animals, and they’re also smart enough to learn the routine of everything within their territory. They’ll know which houses have the people who go to work, which houses have a dog, if that dog is behind a fence, if that dog is little, if it’s an edible dog.

I’ve read about coyote sightings in DC. Will District residents see more of them?

They probably won’t. Yet. That’s usually an accident on the part of the coyote. They’re not like red foxes. Red foxes have evolved to the point that they’re comfortable in an urban setting. You didn’t use to see red foxes—they were almost strictly nocturnal. They wouldn’t come anywhere near people, so there’s been an evolutionary behavior change, and I think you’ll see the same thing with coyotes.

We’re going to get to that point, but we can push that further into the future if people have a standing response that when they see a coyote, they make some aggressive action toward it. Act like you’re going to chase it. Make noise. I recommend a can of compressed air, like they use at football games. Or a pot with rocks in it. Once they become comfortable, we’ve got a problem.

What precautions should people take when they’re on wooded trails? Should they turn off their iPods?

An iPod isn’t going to make much difference as far as coyotes and bears go. Predators don’t make much noise. If they did, they would go out of business. Walkers and joggers should always remain alert. A small air horn would be a good item to carry—it would frighten a wild animal but also serve as a great attention getter if someone needed help. Statistically speaking, the most dangerous threat on our trails is probably the tick.

What about foxes?

A fox is harmless. If you take a fox and remove that fluffy pelt, it looks like a whippet dog. A big red fox weighs about 12 pounds—most house cats are heavier. A predator is looking for something it can overwhelm and take quickly.

Couldn’t the fox have rabies?

Any mammal can get rabies. Yes, they’re a threat then, but it’s too broad of a brush to say a fox is a threat just because he’s in your neighborhood. There are no neighborhoods that don’t have foxes. Every yard in Fairfax County is probably visited by a fox at least once in a 24-hour period.

How can you tell if an animal is rabid?

People are under the misconception that a rabid animal is foaming at the mouth. Of all the rabid animals that came through animal control in the 11 years I was there, I only saw one that was foaming at the mouth. That is not a typical symptom.

Most of the ones that come back positive for rabies don’t look sick. It comes down to behavior. Any animal showing signs of aggression toward people, itself, or inanimate objects is nearly always rabid. Bats would be suspect if they’re on the ground. Raccoons seen during the middle of the day, out in the open, would be abnormal. A red fox seen during the day has become common, but a gray fox seen during the same period would be suspect.

Any exciting moments from your work?

The most exciting would include a Cape-buffalo charge, accidentally walking into a group of timber rattlesnakes and copperheads in the mountains of Virginia, catching a golden eagle by hand, and a close encounter with a brown bear in Alaska.

What happened with the brown bear?

It was on the Alaskan peninsula in a remote tent camp. I’d walked a few miles from camp, up on this bluff. At the bottom of the hill, a stream fed into a lake. On the other side of the stream, a big marshy area ran a mile and a half. I had a camera with a telephoto lens. I saw a huge brown bear working its way down the stream.

The lens cap was a metal screw-on cap. I was trying to turn that slowly and quietly. I finally got it off and took a few photos, and by then the bear was directly below me. I couldn’t see him. It went from fascination to “Uh-oh. Where is he?”

I backed out of there quietly. I walked backward for about half a mile. These bears looked like Volkswagen buses. They probably weigh 900 to 1,000 pounds. I filed that away as one I wouldn’t forget.

What have you learned about life?

Nature has a resilience that even man cannot destroy.

This article first appeared in the July 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.