They’ve lost loved ones to plane crashes and suicides. They’ve survived polio and torture. They’ve had coworkers gunned down. They get diagnosed with brain tumors.

It sounds like an Oprah reunion, but these are members of the United States Senate.

Many people think of the Senate as a place filled with millionaires who lead charmed lives. In reality, their personal lives seem less charmed than the lives of many Americans.

Everyone experiences sadness in life—a broken marriage, a serious injury, the deaths of loved ones. That holds true for politicians too, but a surprising number of senators have suffered an extraordinary tragedy in their lives.

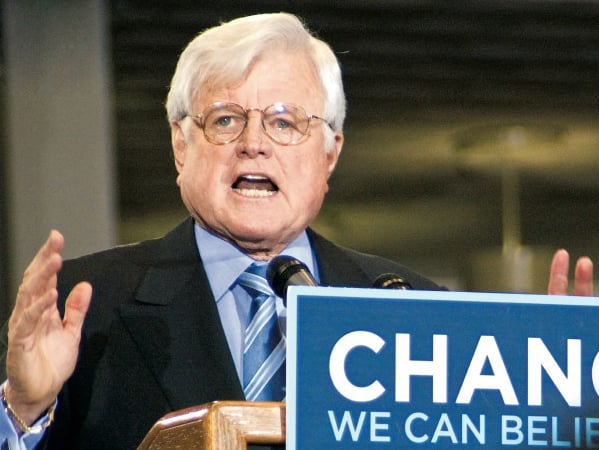

Even in an era of partisanship, senators come together in times of grief. There was an outpouring of emotion among his colleagues when Ted Kennedy was diagnosed with a brain tumor in May. Kennedy, the dean of Senate tragedy, has often been the hand that reached across the aisle in others’ times of sorrow.

Shared experiences of loss and compassion are one of the few ties that still bind, influencing how senators relate to constituents and how they speak to one another amid intense political polarization.

“People have a lack of understanding of senators,” Republican Rick Santorum said as he walked nostalgically down the Senate corridors shortly after losing his reelection bid. “They see us like these statues,” he said, gesturing at the marble around him.

“But we are human. We have personal lives. And we do learn to see each other as people,” said Santorum. One of the first phone calls he got after the death of a premature baby was from Kennedy, whom Santorum at one time viewed as the devil of liberalism incarnate.

Pilgrimages of Faith

Politics was not always as bitter as it is today. Historians and longtime senators say that for most of history there were more votes across party lines, more camaraderie. Senators lived here with their families. They attended the same churches, knew one another’s wives and children. They cut legislative deals on the golf course.

In the late 1950s, jet travel made it easier for senators to return to their home states. The Dirksen and Hart office buildings were added, and the number of staffers exploded, limiting the interaction of senators with colleagues. Spouses embarked on careers, leaving less time for socializing. Fundraising demands kept lawmakers on the road. “We get to know each other only on trips now,” says Connecticut Democrat Chris Dodd, recalling the lively conversations and bipartisan laughter around his parents’ table when his dad was a senator in the 1950s and ’60s.

Now instead of the golf course or the poker table, senators have the prayer breakfast—not the flashy one with the motorcades reported on TV but the quiet one that convenes in a private dining room in the Capitol every Wednesday morning, a tradition that dates back at least 40 years. No staff, no cameras, no spin. Just what Senate chaplain Barry Black calls “an opportunity to engage in judicious self-disclosure.” Members say it gives them a chance to see one another as people.

“It’s very private, very bipartisan,” says Tennessee Republican Lamar Alexander. “Each week, a member tells about his or her life.”

About 15 to 20 senators attend nearly every meeting, while another dozen drop in frequently. Many others, even those not publicly thought of as spiritual or religious, come now and then or when they are invited to “sum up their faith pilgrimage,” says chaplain Black.

“Friendships are formed,” he says. “And certain stereotypes are eradicated.”

“You’d Be Really Shocked”

Some Senate tragedies are well known. Democrat Robert Byrd has spoken of the aunt and uncle who took him in as a baby after his mother died in the 1918 flu pandemic. Weeks after Delaware Democrat Joe Biden’s 1972 election, his wife and 13-month-old daughter were killed in a automobile crash.

Oregon Republican Gordon Smith turned personal grief into a mental-health crusade after his son hanged himself the day before his 22nd birthday. Pete Domenici, a Republican from New Mexico, has agitated for better health insurance for mental illness after going public with his daughter’s schizophrenia.

Among Senate leaders, Harry Reid’s miner father killed himself, Dick Durbin’s dad died of lung cancer at 51, and Mitch McConnell contracted polio at age two and was not allowed to walk for two years.

The scars don’t stop at the leadership level. Alaska’s Ted Stevens, the senior Senate Republican, walked away from a plane crash in 1978. His wife, Ann, was killed. Maine Republican Olympia Snowe, orphaned by nine and widowed at 26, eventually remarried only to have a stepson she adored collapse on a Dartmouth baseball field with a fatal heart defect. Maryland’s Ben Cardin lost his 30-year-old son to suicide. Ohio Republican George Voinovich’s nine-year-old daughter, Molly, died when she was hit by a car in 1979.

California Democrat Dianne Feinstein had barely gotten over the trauma of losing a husband to cancer in her early forties when two colleagues were assassinated in San Francisco’s city hall. She was stained with Harvey Milk’s blood as she tried to find his pulse. A young Jay Rockefeller was dating the woman who would soon become his wife when her twin sister was stabbed to death in her bedroom in a murder that remains unsolved after 40 years.

Former senators have their stories too. John Edwards and Mike DeWine lost children in car accidents; the Edwards family is now dealing publicly with wife Elizabeth’s incurable breast cancer. Lincoln Chafee had a sister die in a horseback accident; Don Nickles’s father committed suicide. Conrad Burns’s teenage daughter died of carbon-monoxide poisoning.

Those are the stories that have been revealed. Behind closed doors, chaplain Black says, other tales are told. “You’d be really shocked,” he says.

All the Doors Get Opened

Black isn’t sure if the Senate has a disproportionate number of losses or whether, as a pastor, he hears more about human suffering. But he’s convinced that the nature of high-stakes decision-making leaves lawmakers far more thoughtful and that their stressful jobs, with choices about war and peace—or life and death—leaves them more “spiritually vulnerable” than the public would imagine.

A generation ago, many of these stories would not have unfolded so openly. A senator was typically the strong, silent type. If he had a personal trauma that was known, it may have been a war wound. Daniel Inouye, the Hawaii Democrat who lost an arm on an Italian battlefield in 1945, is the last of the disabled-warrior senators of his generation. John McCain’s slightly off-kilter gait is a reminder of his torture as a POW in Vietnam.

When personal revelations were unavoidable, they came in a subdued press release, like the news in 1986 that Jake Garn, then 53, had donated a kidney to his diabetic adult daughter. Personal disclosures were rare. When another former senator, Florida Republican Paula Hawkins, described at a 1984 Senate-sponsored conference on child abuse her own abuse by a neighbor, “people went nuts,” recalls Chris Dodd.

That was before Bill Clinton brought his confessional style of politics to town and Oprah Winfrey and others encouraged soul-baring on TV. The press, in a trend that sharpened after disclosures about the Kennedy presidency and Watergate, also redefined the line between public and private lives.

Senate associate historian Donald Ritchie believes that sports coverage has contributed to the way we now see politicians. Two network news executives, Roone Arledge at ABC and Van Gordon Sauter at CBS, had made their names as sports producers, introducing personal narrative about athletes. If Olympians didn’t have a dying parent to inspire them or a career-jeopardizing accident to rebound from, “they didn’t get much coverage,” Ritchie says. The up-close-and-personal approach carried into news and into politics.

“There is an expectation now—we want to know what a candidate is like,” says Candice Nelson, a political scientist at American University. Confession or disclosure is the flip side of the more aggressive and intrusive press coverage: “It’s almost like the politicians were saying, if you are going to criticize me for doing those things, then also let me tell you the personal stuff that I can connect with my constituents, or that have hurt me, that have been painful in my life.”

Take former senator Dale Bumpers. The Arkansas Democrat was 70 years old and into his third decade of public service when, to borrow a phrase from fellow Arkansan Clinton, he let his colleagues feel his pain. During a 1995 debate on highway safety, he held the Senate spellbound recounting the day his teetotaler parents were heading home after checking their spinach crop.

“They were on a narrow highway with no shoulders, and they came up over a slight hill, just a slight incline, at about dusky dark—the wrong time, wrong place,” said Bumpers, who was attending law school on the GI Bill at the time of the accident. A drunk driver hit their vehicle. Both parents died of their injuries.

“We’re much more open now, and I think that’s good we talk about our problems,” says Iowa Democrat Tom Harkin, who has served since 1985.

Harkin is more skeptical than many of his colleagues that the new openness can mitigate the damage caused by modern partisanship, but he does acknowledge that shared experiences can lead to openings for bipartisan initiatives. “The personal experiences can lead you to an issue, and then you find others who share it,” he says.

Harkin and former Florida Republican Connie Mack worked together on bills aimed at preventing and treating cancer; both of their families have endured more than their share of the disease. Sensitized to the discrimination his deaf brother, Frank, faced, Harkin also partnered with Bob Dole, a disabled World War II veteran, to pass the Americans With Disabilities Act in 1990. Both Dole and Harkin consider the ADA among their proudest achievements.

Gruff conservative Pete Domenici found common cause with the loquacious liberal Paul Wellstone on mental-health-insurance parity before the Minnesota Democrat died in a plane crash in 2002. Domenici by then had gone public with his daughter’s schizophrenia; Wellstone’s brother also suffered severe mental illness.

After Byron Dorgan, a Democrat from North Dakota, heard Mike DeWine, a Republican from Ohio, reflect on daughter Becky’s fatal accident, Dorgan confided the story of his daughter Shelly, a newlywed who died at age 23 after a heart operation that should have been routine. For the next 14 years, until DeWine was defeated in 2006, these two were the Senate’s go-to guys on any bill involving organ donation.

“There are only 100 of us. You find that you share the same problems; you share, you know, the same emotions,” DeWine said before leaving the Senate. “And you find that nobody is worthy of being demonized.”

“A Different Kind of Life”

For some senators, tragedy early in life was a force that propelled them into politics.

At age 11, Utah Republican Orrin Hatch lost a big brother in World War II—an experience shared by Kennedy, among his dearest friends in the Senate.

“It pushes me,” says Hatch. “I’m making up for my brother’s death. I’m fulfilling a mission for Jesse. Every day I think about him, about being here for him and for my parents.”

Florida Republican Mel Martinez believes that the four teenage years he spent in foster care in Orlando, separated from his parents after the Cuban revolution, sharpened his understanding of community. Oregon Democrat Ron Wyden says he has dedicated much of his career to healthcare because of all the families he saw “get jostled and pummeled by the system” in the 30 years that his brother struggled with schizophrenia.

Here in Washington, Olympia Snowe doesn’t talk much about her early life, but back home with constituents, particularly young women, she is more apt to talk about her mother’s death when she was eight, her father’s when she was nine, her first husband’s fatal car accident when she was 26, and her stepson’s death after his collapse on the ball field.

“Early on in my life, I realized that I had two choices—either allow myself to become overwhelmed by tragedies or learn something from them,” she told at-risk girls at a residential center back in Maine one summer day.

For Gordon Smith, tragedy almost had the opposite effect, nearly pushing him out of politics. After his son’s suicide, Smith was overwhelmed by the support he had within the Senate. Then–majority leader Bill Frist adjusted the vote schedule around the funeral, and six senators attended the service in a Mormon chapel on a hilltop in Pendleton, Oregon. Among them was his fellow Oregonian, Democrat Wyden, whose schizophrenic brother had recently died after a decadeslong struggle.

Despondent, Smith had trouble seeing purpose in the Senate and nearly quit. When he eventually was reenergized politically, he was less ambitious in terms of his party’s hierarchy and more moderate. He dropped a plan to seek a Republican leadership post, threw his energy into passing legislation to prevent teen suicide, and fought fellow Republicans over Medicaid budget cuts that would have hurt mentally ill people.

“A public life is a different kind of life,” says Dorgan, who still keeps in his office the white Bible that Hatch gave him after his daughter’s death. “We all live life on a tightrope—but we are living it out in public.”

That can put politics in perspective.

“People around here talk about having to take a tough vote,” says Dorgan, who also lost his mother in an accident when police were chasing a drunk driver. “But some of us know what ‘tough’ really is.”

Have something to say about this article? Send your thoughts to editorial@washingtonian.com, and your comment could appear in our next issue.

This article appears in the July 2008 issue of Washingtonian. To see more articles in this issue, click here.