Twenty years ago, I played my last foot-ball game: a 23-16 loss in the Massachusetts Division 6 Super Bowl during a New England snowstorm. As team co-captain, I held the runner-up trophy and said to my head coach: “I wish it could have been the real thing.” Then I ran off the field and closed a chapter I thought I’d never experience again.

Growing up as the first son of Korean immigrants, I saw two important distinctions in football. First, it was an equalizer, bringing parity to the inequities of middle and high school. “I’ll see you on the practice field” was all it took to avoid conflict, diffuse tension, and mitigate insults. And it was an outlet, providing a chance to unleash pent-up frustrations created by the expectations of success. My achievements meant justification for my parents’ untold sacrifices—working together nearly 40 years, without a day off, to build a modest cafe business so I could be the first in the family to go to college—a narrative shared by many children of immigrants. I often carried this burden onto the football field.

Practices were brutal—physically unrelenting and mentally exhausting. I always dreaded camp in August. But football became a way of life. And then one day it was over. I couldn’t have imagined how much I’d miss it.

Over the years, the emotions surrounding football buried themselves deeper. The intensity and passion I’d once felt for the sport subsided into the excitement of a spectator and finally into casual enjoyment. There would no longer be a bridge between the lessons of the game and the lessons of life. Like how football taught me that to succeed, you need to get the fundamentals right. As coach Vince Lombardi said: “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.”

Then two years ago, my seven-year-old first son signed up for McLean Youth Football. As I helped him try on his pads, I was overcome. Passions I thought I’d permanently put away began to simmer. I saw the excitement in his eyes and knew exactly what he was feeling. I held him and told him how proud and grateful I was that he’d brought football back into our home.

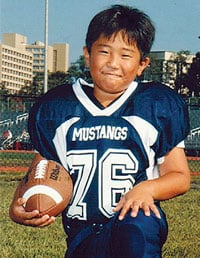

Today I’m an assistant coach for my son’s McLean Mustangs, and the emotions I buried two decades ago have resurfaced in full. Only this time, the richness of these feelings overflow naturally. More than the wins and losses, I find myself deeply satisfied in teaching the game. I appreciate every opportunity to convey a coaching philosophy to young people. I’ve also realized that in 20 years a lot has changed. Most notably, as coaches we’re much more cognizant and educated—and certified—about head injuries. Many of the practice drills I ran in youth and high-school football are outlawed now. Playing “ironman” football is a rarity. But the basic approach remains the same. Football will always be the greatest team sport, an experience that extends beyond the game itself.

The biggest joy has been seeing my son learning and applying the principles of effort and commitment alongside his teammates. At times I wish I could be the one under his helmet. Though I’ll never be able to, a part of me is on the field again. And unlike the runner-up trophy of 20 years ago, this time it’s the real thing.

Thomas S. Kim is president of Thomas Capitol Partners, an international government-relations firm.

This article appears in the December 2013 issue of Washingtonian.