On New Year’s Eve in 2005, a small group of CIA officials had their evening plans cut short by an urgent message from the White House. President Bush’s advisers had learned that James Risen, a reporter at the New York Times, was about to blow the lid on the CIA’s five-year-long plan to derail Iran’s nuclear-weapons program.

Risen had devoted a chapter in his new book, State of War, to a covert operation called Merlin, which involved a high-stakes gamble to feed the Iranians blueprints for a nuclear-triggering device. The blueprints contained a hidden flaw, and the CIA bet that Iranian engineers would waste years trying to build the component to no avail. The agency thought Merlin was the United States’ best chance of keeping Iran from building an atomic weapon. To expose Merlin now would tip off Iran to what America’s spies had been doing and what they might try in the future.

Bush’s White House aides looked for a way to stop Risen’s book from reaching the shelves. They considered whether his publisher, Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, could be persuaded or even required to halt the release. But the book was due to go on sale in three days. Short of standing in the way of the delivery trucks, there was no way of keeping the information from public view.

The White House made photocopies of Risen’s chapter on Merlin and sent the pages to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley. There, the senior officers who’d been “read in” to the Merlin program were shocked by Risen’s detailed account of it.

He revealed that the agency had used a former Soviet nuclear engineer, a post–Cold War defector, to deliver the blueprints to Iranian diplomats in Vienna at Iran’s mission to the International Atomic Energy Agency. The Russian was to pose as an unemployed scientist, hoping to sell nuclear secrets. Once the Iranians saw what the Russian carried, the CIA thought Iran would be eager to buy the plans for Tehran. But Risen also revealed that the flaw in the blueprints wasn’t well hidden. The Iranians could disregard it and use the rest of the design to accelerate their weapons program, which was the opposite of what the CIA had intended.

Risen’s chapter read like a spy novel. Written partly from the scientist’s perspective, it contained his personal thoughts and misgivings as well as dialogue the scientist had had with his CIA handlers.

“My God,” thought one CIA official who had worked on the program as he read Risen’s chapter, “who gave him all this information?”

Risen’s book revealed other intelligence gaffes, including a 2004 incident in which the CIA inadvertently revealed the identity of its own spies in Iran to the Iranian foreign intelligence service. The spies were identified and taken out of commission. That gaffe, combined with the dangerous Merlin mission, raised a troubling question, Risen writes: “whether the CIA is blind in Iran, unable to provide any significant intelligence on one of the most critical issues facing the United States—whether Tehran was about to go nuclear.”

Inside the CIA, senior officials exploded.

“There’s no question,” another former senior CIA official says, “that by showing that kind of leg to the Iranians, they know a lot more and can surmise a lot more about what we’re doing and how we’re doing it. And that affects other activities.”

To get the kind of detail in the Merlin chapter, Risen’s sources had to give him, or point him toward, some of the most tightly held secrets in American intelligence. He’d gotten to the heart of Merlin, which, as the other former official describes it, involved some high-tech ideas that hadn’t been used in the field. “It was very Buck Rogers,” the former official says. “To reinitiate that type of technical program against the Iranians would be exponentially more difficult if they had read Risen’s book.”

But was the CIA crying wolf? By the time State of War hit bookstores, the agency was shutting down Merlin because it hadn’t produced much useful intelligence. Also, the total price tag for the operation was approaching $100 million. Judged by its original goal—to set back Iran’s nuclear program—Merlin was a failure. Arguably, the public had a right to know that, particularly because government officials were hinting at military strikes in Iran to degrade its capacity for making weapons.

But classified information had been breached, so the Justice Department began an investigation into who had leaked to Risen. As in every leak investigation, anyone on the intelligence community’s so-called “bigot list”—the names of people cleared to know about a program—could be interviewed, and that person would be asked about any previous contact with the reporter. The former CIA official remarks that he’d never met Risen “but I hope he rots in jail.”

This wasn’t the first time Risen had tangled with secretive government officials. Less than a month before the publication of State of War, President Bush had called the top editors of the New York Times to the Oval Office to dissuade them from publishing another blockbuster, this one an exclusive that Risen had written with fellow reporter Eric Lichtblau about potentially illegal surveillance of Americans’ phone calls and e-mails.

President Bush had authorized the secret surveillance program shortly after the 9/11 attacks, and he believed it was one of the most fruitful sources of intelligence about terrorists’ plans and the inner workings of their organizations. Bush warned the Times staff that it would be held responsible if the story helped al-Qaeda and other terrorists figure out how America was spying on them.

The editors weren’t persuaded that the intelligence value of the program outweighed the public’s right to know about it, particularly because the reporters had learned of a pitched battle within the senior ranks of the administration over whether the program had broken a law on monitoring American citizens. The newspaper published the story on December 16, 2005, and the next day Bush fumed in his weekly radio address that the leak “puts our citizens at risk . . . alerts our enemies, and endangers our country.” Now the administration was up against the same tenacious reporter.

This also wasn’t the first time the White House had tried to flag Risen off the Iran story. In early 2003, Risen had intended to write about Merlin in the Times. CIA director George Tenet asked Risen and his editors to meet him and national-security adviser Condoleezza Rice at the White House. According to a former intelligence official and another source familiar with the events, they argued that exposing the operation would damage US national security and hamper the CIA’s efforts. Tenet and Rice made a persuasive pair—the Times editors spiked Risen’s story.

At the end of January 2008, two years after the leak investigation began, the Justice Department delivered a subpoena to the New York law firm Cahill Gordon & Reindel, which was representing Risen. It ordered the reporter to appear before a grand jury in Alexandria, where prosecutors would presumably try to force him to identify his Merlin sources.

If he refused to testify, the judge could find him in contempt and confine him to jail until he changed his mind. He could also face financial penalties. Less than month after Risen got his subpoena, a judge ordered former USA Today reporter Toni Locy to pay fines totaling up to $5,000 a day for refusing to comply with a demand to know her sources. The judge said Locy would have to pay the fine out of her own pocket.

“We intend to fight this subpoena,” Risen’s lawyer, David N. Kelley, told the Times. Kelley had been a federal prosecutor earlier in the Bush administration. “[Risen] will keep his commitment to the confidentiality of his sources.”

Leak investigations are usually unproductive. Defying the perception of secrecy in the world of spycraft, the number of people who know about even the most highly classified program can be in the hundreds. It’s rare that investigators identify a suspect, and rarer still that they bring an indictment and go to trial, because the accused could end up revealing more classified information in his defense—a kind of “graymail” that ensures that most leakers will never spend time in prison. From 2005 to 2009, federal agencies referred nearly 200 leaks to the FBI. Investigators opened 26 cases, identified 14 suspects, and prosecuted none of them.

Reporters make attractive targets for investigators who need confirmation of a leaker’s identity. But historically, the Justice Department has set a high bar for questioning journalists. Recognizing that the freedom of the press is only as broad as the freedom of individual reporters to investigate and publish the news, federal prosecutors are restricted from compelling media testimony except under specific circumstances.

According to Justice Department regulations first issued in 1970, the prosecutors must exhaust all available means of figuring out who the leaker is; that includes taking testimony from government officials and possibly conducting hundreds of interviews. The prosecutors also have to make their subpoena case to the attorney general, who must personally approve it. The information the government seeks must bear directly on the case at hand, and in criminal cases—which the Merlin leak was, because the operation was classified—it must be “essential to a successful investigation—particularly with reference to directly establishing guilt or innocence,” the guidelines say.

It’s impossible to know how many times federal and state governments have issued media subpoenas. The documents aren’t publicly disclosed. There also is no official tally of subpoenas issued in civil cases, which are often brought in libel and privacy suits by plaintiffs who think a journalist can identify their detractors.

Risen’s 2008 subpoena expired with the term of the grand jury. Media watchers and intelligence officials presumed that the Merlin investigation would go the way of most fruitless searches. But after reviewing leftover leak cases from the Bush administration, the Obama Justice Department decided to revive this one. In April of this year, Risen received another subpoena to appear before the grand jury in Alexandria.

Why the government chose to pursue the case again remains unclear. Nor is it publicly known whether the prosecutor has expanded the scope of the subpoena and is seeking more information than just who leaked about Merlin. State of War also contains allegations of CIA ineptitude from the mid-1990s, years before the Iran operation began.

But what is known is that the Merlin leak presents some unusual circumstances. According to former intelligence officials with direct knowledge of the program, it was closely held within the CIA. Not many officials knew of its inner workings, so the list of potential leakers was short. That makes the government’s pursuit of Risen puzzling.

According to one former official, the government believes it has already identified a suspect, which could make Risen’s testimony not only unnecessary but also a violation of the department’s own guidelines on media subpoenas.

“They already know who it is,” says the former official, who describes the suspected leaker as someone who is no longer employed by the CIA and who officials are confident was a source for Risen’s chapter.

There are also indications that the judge presiding over the grand jury doubts the need for Risen to identify his source. Another former official says that on this second go-around, the judge wasn’t prepared to enforce a subpoena unless the Justice Department ran it through its internal approval process again. That meant reviewing the need for the subpoena and taking it to attorney general Eric Holder, who ultimately signed off.

According to media lawyers, making prosecutors repeat the process is a sign that the judge thinks they should move ahead with their case—without Risen’s testimony.

“It’s somewhat comforting to know the judge put them through the paces,” says Chuck Tobin, a former journalist and a partner at Holland & Knight. “But it’s still disturbing. If they know who the leaker is, why do they need Risen to point fingers? Reporters are supposed to be the witnesses of last resort.”

Risen’s current attorney has said he’ll fight this subpoena, too. The Justice Department won’t comment on whether prosecutors have identifie

d a suspect or on any other aspects of the case, which is under seal. But spokesman Matt Miller pushes back on the notion that prosecutors can subpoena a journalist only when they truly don’t know who his or her source is: “The rules are that the department has to make every reasonable attempt to get the information from other sources before even considering a press subpoena.” They can only use a subpoena “to obtain essential information that can directly establish guilt or innocence.”

But if the Justice Department now believes that it can force journalists to testify even if investigators believe they know who the leaker is, it would mark a shift in the balance of power between the government and the press.

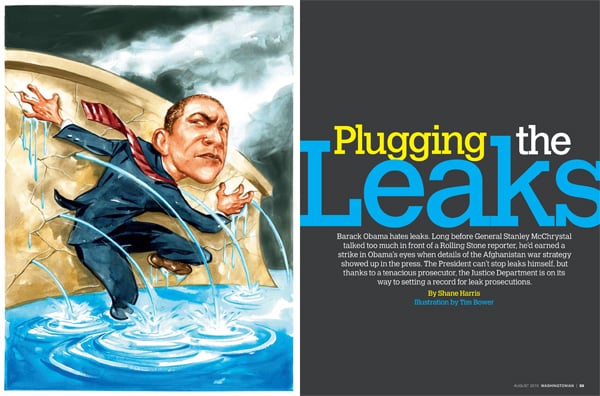

As consequential as this shift would be, it’s in keeping with the Obama administration’s embrace of secrecy. Officials have been so aggressive in pursuing leaks that the President appears less tolerant of unauthorized disclosures than George W. Bush, who accused journalists of aiding and abetting America’s enemies.

Newsweek reporter Jonathan Alter’s book The Promise: President Obama, Year One describes the particular—and according to some White House staff, pointless—obsession that the President has with those who speak out of turn.

Alter writes that “no one on his staff was brave enough to tell [Obama] that obsessing over leaks was a colossal waste of time. But it wouldn’t have mattered: leaks offended Obama’s sense of discipline and reminded him of everything he disliked about the capital. He was fearsome on the subject, which seemed to bring out his controlling nature to an even greater degree than usual.”

Off-the-record gossip, reported innuendo, and even damaging leaks are staple transactions in Washington. They are the lubricant in a symbiotic spin machine that, in the long run, serves the interest of the presidency and the press. Trying to stop leaks is a Sisyphean task, but that hasn’t stopped Obama from trying.

The administration is on the verge of being the first in US history to see two people sentenced for disclosing classified information in a single presidential term. In May, Shamai Leibowitz, a Silver Spring linguist who had worked for the FBI on contract, was sentenced to 20 months in prison for giving classified information to the host of a blog. And in April, the Justice Department indicted a former National Security Agency official, Thomas Drake, for allegedly leaking classified information to a reporter at the Baltimore Sun. If convicted, Drake could spend decades in prison.

The military also filed criminal charges in July against Bradley Manning, a 22-year-old Army specialist from Potomac who allegedly leaked government secrets to the Web site WikiLeaks. Manning is believed to have given the site footage of an Apache-helicopter strike in Iraq from 2007 that killed civilians and two news reporters. The footage caused a sensation when WikiLeaks posted it in April with the title collateral murder. Manning is also suspected of having given the site more than 250,000 secret diplomatic cables, which he may have copied off a government computer system in Iraq.

The math is telling: Taken together, the Manning investigation, the Leibowitz and Drake cases, and the Risen subpoena suggest that the Obama administration may go down in history as the most anti-leak of all.

Risen would make a tantalizing target for any administration. He has built his reputation by exposing questionable and potentially illegal activities in some of the most opaque corners of the government. He is an extraordinary reporter, and he inspires extraordinary animus among his targets.

“He’s a pain in the ass,” one former intelligence official observes. Says another: “I’d like to run him over with my car.”

Risen regards powerful establishments with skepticism, a view that has fueled his reporting. He joined the Washington bureau of the Los Angeles Times in 1990 as an economics correspondent. But he switched to the CIA beat five years later, not long after CIA officer Aldrich Ames was convicted of spying for the Soviet Union and, later, the Russian government. Risen joined the New York Times in 1998. His work has focused less on the political rulers that come and go than on the bureaucratic class, the career officials who remain in power for decades and run the government. They are often the targets of his reporting and often the ones who hold him in the highest contempt.

“The career folks at the Justice Department have been monumentally ticked off at Jim Risen for a long time,” says Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. “Jim is a serious reporter. He believes that if we don’t aggressively cover national security, people will run amok.” Risen himself has said the best reporter is a “curmudgeon” who asks the questions no one else will.

It’s tempting to view Risen’s subpoena as a form of institutional payback. One theory among reporters is that by prosecuting him for information in his book, as opposed to his New York Times articles, the administration avoids picking a fight with the most revered journalistic institution among the left.

But if the Obama administration is trying to send a message with this subpoena, it’s not meant for Risen alone. The implied threat is broader, and it’s clear to every reporter in town: If we can go after Jim Risen, we can go after anyone.

To go after Risen, Drake, and other loose-lipped antagonists, the administration has chosen a crack prosecutor. William Welch was, until last year, head of the Justice Department’s public-integrity section, which prosecutes government officials and corruption cases.

The son of a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, Welch joined the US Attorney’s office in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1995. He prosecuted a string of cases, including firearms possession, murder, and mortgage fraud. In 2006 he was named deputy chief of Justice’s public-integrity section in Washington, and he took over the top job a year later. Welch oversaw the indictment of Kevin Ring, who worked with the notorious lobbyist Jack Abramoff. He also had ambitions of becoming the US Attorney in Massachusetts, the state’s top federal law-enforcement job.

Welch has chosen at least two George W. Bush–era leak cases to pursue—Risen’s subpoena and the prosecution of Thomas Drake, the former NSA official. (Reports of a third prosecution are in the offing, involving a leak about North Korea policy to a Fox News reporter.) But while Welch’s prosecutorial chops are formidable, he’s an unlikely candidate to head politically charged investigations.

Last October, Welch stepped down from his public-integrity post amid a criminal investigation into whether he and his staff had mishandled evidence in the corruption trial of former Alaska senator Ted Stevens. The Senate’s longest-serving Republican was convicted in October 2008 of seven counts of lying about gifts on financial-disclosure forms. Allegations surfaced that the prosecution had withheld exculpatory evidence from Stevens and that FBI investigators had engaged in unethical conduct.

Ironically, the controversy that finally forced Welch from his job stemmed from allegations by a confidential source. After the senator was convicted, Chad Joy—an FBI agent in Alaska who had worked on the team that investigated Stevens—filed a complaint that accused government officials of “possible criminal violations.” Joy said that the lead FBI agent had had an inappropriate personal relationship with the government’s key witness and that she’d once met him alone in a hotel room. He also accused one of the Justice Department lawyers, whom Welch oversaw, of trying to prevent a witness from testifying for the defense and of keeping from the defense team information that it had a right to see. Some of the information withheld from Stevens contradicted a key prosecution witness who testified against him at his trial.

At a hearing in December 2008, Welch and the prosecutors argued that because Joy had asked for official protection as a whistleblower, the court had to keep his identity a secret and put his complaint under seal. That meant that Stevens’s lawyers couldn’t see it. Welch was acting like a journalist, claiming that if whistleblowers couldn’t be assured that their identities would stay a secret, they would be unlikely to reveal misconduct for fear of reprisal.

For reasons unclear at the time, Welch reversed the government’s position a month later, telling the judge that FBI agent Joy had been denied official whistleblower status. Baffled by the government’s change in position, the judge held another hearing. According to the newspaper Legal Times, he “appeared furious, angrily pointing his finger and raising his voice” at Welch and the government’s lead attorney.

On January 16, 2009, the judge ordered the attorney general to explain the discrepancies in what the government’s lawyers had told him. It appeared, the judge wrote, “that several attorneys in this matter . . . may have intentionally withheld important information from the court.”

An internal Justice Department ethics office opened an investigation, and the judge named a special prosecutor to look into Welch’s and other government lawyers’ behavior. Attorney general Holder, who had worked in the public-integrity section after graduating from law school, decided to drop the botched case in April 2009 and not to pursue a new Stevens trial. Welch returned to Massachusetts.

The Justice Department hasn’t said why Welch got the leaks job. But he appears to have a strong defender in Lanny Breuer, the head of Justice’s powerful criminal division, which oversees Welch’s old section. When Welch stepped down, Breuer praised the embattled attorney, calling him “a dedicated public servant” and “an extremely smart and thoughtful lawyer.”

“Bill’s shoes will be hard to fill,” Breuer told reporters at a news conference in October. “I think he’s an extraordinary person and a thoughtful lawyer. Bill and I have grown close.” Welch’s lawyer told the Washington Post, “Bill knows that his management decisions, where permitted, comported with his own and the department’s highest ethical standards.”

David Hoose, a criminal-defense attorney in Northampton, Massachusetts, who squared off against Welch in court, calls him one of the most dogged prosecutors he’s ever encountered. “He’s the only prosecutor I’ve encountered who I couldn’t outwork,” says Hoose, who defended clients against Welch in white-collar cases and a high-profile murder trial. “The guy is tireless. He’ll work 18 hours a day. He’ll just wear you out.”

“Once he sets his sights on someone, he’s like a piranha,” Hoose says. “He’s on them with everything he’s got. Yet at the same time, I would not expect him to cheat.”

On the subject of unauthorized leaks, Hoose says, “I suspect he might be rather zealous on the issue. I think that he is a government lawyer through and through. My suspicion is he would be quite annoyed with any government employee who breached classified information.”

The government has battled for nearly a century to restrain the press from publishing leaked secrets. The fight usually heats up in wartime. In 1917, two days after the United States entered the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson urged Congress to pass the Espionage Act, which provided prison terms for sabotage and spying and which Wilson wanted to direct at journalists who published information that might help the enemy.

Fifty-four years later, the Nixon administration tried to stop the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing articles on the so-called Pentagon Papers, a damning classified history of the United States’ military and political efforts in Vietnam. The Supreme Court ruled, 6–3, that prior restraint of the press violated the Constitution.

But eight months later, the Court heard arguments in Branzburg v. Hayes, a collection of cases in which reporters had tried to fend off federal subpoenas to identify their confidential sources and assist FBI investigations. One case involved a New York Times reporter who had infiltrated the ranks of the Black Panthers, something the FBI found hard to do on its own.

The journalists asserted a “reporter’s privilege,” similar to the confidential relationship between an attorney and his or her client. They argued that the government couldn’t force them to testify about their sources and what they might have told them. The court ruled against the reporters, but James Goodale, the attorney for the Times, devised a clever argument: The justices had actually created a reporter’s privilege, even though, on its face, their ruling said just the opposite.

Justice Lewis Powell had decided against the reporters, but Goodale thought he hadn’t ruled out the idea of a privilege in other cases. Powell wrote that the “proper balance” between freedom of the press and the obligation for people to testify in a criminal matter should be judged “on a case-by-case basis.” In notes written before he authored his opinion, Powell made clear he didn’t intend to establish a constitutional privilege. But Goodale saw enough wiggle room to develop a strategy. For the next 30 years, attorneys seeking to quash subpoenas argued that judges should enact a “balancing test,” weighing the interests of reporters’ pledges to sources against the government’s mandate to pursue justice. The balancing test was widely adopted, and it helped many journalists avoid giving court testimony.

Then terrorists struck the United States on September 11, 2001. The Bush administration was already hostile to a nosy press and the public disclosure of presidential records. In 2003, against the backdrop of war and secrecy, an influential appeals-court judge wrote an opinion that shattered the balancing test’s foundation.

Judge Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit—an expert on intelligence matters and a prolific author—wrote an opinion explaining why the court had ruled against a group of authors who refused to hand over tape recordings of interviews they’d done with a source. Posner wrote that the interpretation of the Branzburg case was a fantasy. Powell hadn’t created a reporter’s privilege, and those who asserted otherwise had read the justice’s opinion “audaciously.”

Posner acknowledged journalists’ conundrum: The press couldn’t function unless reporters made good on their pledges of confidentiality to sources. But nothing in Branzburg had said that reporters had an “absolute” privilege to protect their sources, he wrote. Courts didn’t need to apply a balancing test. Instead, they needed to “simply make sure” that a media subpoena “is reasonable in the circumstances . . . . We do not see why there need to be special criteria merely because the possessor of the documents or other evidence sought is a journalist.”

Posner had lowered the gate separating the government and the press. And within a few years, federal prosecutors were climbing over it.

In December 2003, a special prosecutor took over an investigation into who may have committed a crime by leaking the name of a CIA officer, Valerie Plame, to news reporters. US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald subpoenaed at least five journalists to testify before a grand jury. The only one who refused to comply, Judith Miller of the New York Times, spent 85 days in jail for contempt of court. But Miller had never written a story about Plame, whose husband, former ambassador Joe Wilson, had written an op-ed in the Times that poked holes in the administration’s claims of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Those were claims that Miller had reported on for the newspaper using anonymous sources, who later proved to be wrong.

“Plamegate” was a watershed for the press, in large part because Miller fought the subpoena and lost. It established a precedent that weakened reporters’ assertion of privilege where the underlying leak might involve a crime. In retrospect, Times executive editor Bill Keller said he wondered whether the paper should have tried to strike a deal with prosecutors, one that would have prevented Miller from having to fight the subpoena and going to jail.

In May 2006, journalists found themselves facing jail time once again. A federal prosecutor subpoenaed two reporters for the San Francisco Chronicle who’d seen transcripts of confidential grand-jury testimony in an investigation of the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO), which produced performance-enhancing drugs for athletes. The reporters linked well-known players to steroid use, including players who publicly proclaimed that they’d never taken drugs. The government wanted to know who had violated the rules of grand-jury secrecy and shown court documents to the reporters.

The BALCO case tested the limits of those internal guidelines that Justice Department lawyers are supposed to follow when subpoenaing members of the media. No national-security issue was at stake, nor was knowing who leaked the grand-jury information, which was a crime, necessary to establish the guilt or innocence of anyone involved in steroid use. The subpoenas were approved by attorney general Alberto Gonzales.

Mark Corallo, the Justice Department spokesman under Gonzales’s predecessor, John Ashcroft, said the prosecutors had broken the department’s rules. “This was an abuse of power,” Corallo told the PBS news program Frontline. “. . . The government just did not meet the standards set by their own guidelines. . . . This one doesn’t even come close. There’s no grave national-security matter here. There is absolutely no harm to life or limb.”

Prosecutors are famously protective of grand-jury secrecy, and at the time, allegations floated that the US Attorney himself might be the leaker. But, Corallo explained, the previous attorney general had set a high bar: The department should subpoena reporters only under “exigent circumstances,” and he took that to mean instances where national security was endangered.

Indeed, the department’s guidelines say that prosecutors should seek to verify only material that’s already published, unless the reporter may have information about a crime that the government can’t obtain through other means. That requirement fit the BALCO case, but the underlying crime involved grand-jury secrecy, hardly an exigent circumstance, Corallo said.

Corallo filed an amicus brief in support of the reporters, and he praised them for doing a public service. “These two guys, Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, cleaned up baseball,” he said.

Before the reporters were subpoenaed, the White House Correspondents Association awarded the

m one of its highest honors. President Bush, a former baseball-team owner, personally thanked the reporters for their service. Ultimately, the pair avoided going to jail for contempt when their source, an attorney who had represented two defendants in the investigation, identified himself.

The gloves had come off. In the wake of the Posner ruling, the Plame case, and finally BALCO, federal prosecutors could feel emboldened in their subpoena power. And journalists, who had long figured they’d be the source of last resort for the government, now had to presume they would be among the first.

In February 2006, attorney general Gonzales raised the stakes. The FBI was investigating James Risen and Eric Lichtblau’s Times story on secret electronic surveillance. At a hearing, Texas Republican senator John Cornyn asked Gonzales whether the government had considered “any potential violation [by the newspaper] for publishing that information.”

“Obviously,” Gonzales replied, “our prosecutors are going to look to see all the laws that have been violated. And if the evidence is there, they’re going to prosecute those violations.”

While judges were approving a wave of subpoenas, the administration also went to extraordinary lengths to investigate old leaks. On March 3, a pair of FBI agents showed up at the Bethesda home of Mark Feldstein, a journalism professor and former investigative reporter for CNN. They demanded that Feldstein hand over decades-old documents that he’d been researching for a book on investigative columnist Jack Anderson, who’d died a few months earlier. When Feldstein asked what crime the FBI was investigating, an agent replied, “Violations of the Espionage Act.”

Anderson’s family had donated about 200 boxes of materials to George Washington University, where Feldstein taught. Feldstein told the agents that the files were “ancient history” and wouldn’t be of much use for current investigations. The agents countered that they could establish a “pattern and practice” of leaking going back to the early 1980s. They were investigating a new espionage case, involving two lobbyists for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee who’d been indicted for receiving classified information. The FBI wanted Feldstein to tell them the names of reporters who’d worked for Anderson and who held pro-Israel views and had pro-Israel sources.

Feldstein didn’t hand over the documents or assist the FBI. He also told the agents it was unlikely anything in Anderson’s files would be of much use. Anderson had been ill with Parkinson’s disease since 1986 and hadn’t done much original reporting after that.

“If the agents had done even rudimentary research, they would have known that,” Feldstein wrote in a Washington Post column. “The fact that they didn’t was disturbing, because it suggested that the bureau viewed reporters’ notes as the first stop in a criminal investigation rather than as a last step reluctantly taken only after all other avenues have failed.”

Reclaiming old notes from a dead reporter employed a legal maneuver that experts said “was surprising if not unheard of,” Adam Liptak of the Times observed in April 2006. An FBI spokesman told the paper that “under the law, no private person may possess classified documents that were illegally provided to them.” Anderson’s status as a journalist gave him no right to possess official secrets, the government argued.

The Times noted that “the administration’s position draws support from an unlikely source . . . .” It was the Pentagon Papers case, generally regarded as a press victory. But in its own reexamination of a Supreme Court opinion, the government noticed that two of the justices had found some basis for prosecuting the Times and the Washington Post after they published their articles, which the papers knew contained classified information.

For journalists, the Espionage Act is frighteningly broad and vague on this question. The Nixon administration considered prosecuting the Times, but a US Attorney in Manhattan decided not to.

In 2006, the government stood a better chance. Another espionage statute, enacted in 1950, forbade publication of “communications intelligence activities.” That put Risen and Lichtblau’s surveillance story in the law’s crosshairs. The 1917 law might also cover them, and it could apply to a major story the Post had run in November 2005 about a global network of CIA prisons used to interrogate high-level terrorists.

As of April 2006, the Times reported, neither it nor the Post had been contacted by government investigators. But two years later, Risen received a subpoena for the Merlin chapter in his book. He has not been indicted under the espionage laws.

But another recent leak case again has again raised the prospect that a journalist could be prosecuted. In November 2005, Thomas Drake, a senior official at the National Security Agency, made contact with a reporter for the Baltimore Sun who’d been covering NSA. As spelled out in a federal indictment of Drake for multiple violations of the Espionage Act, he provided the reporter with classified information about NSA programs in the course of hundreds of e-mail exchanges and at least half a dozen in-person meetings in Washington.

The government alleges that Drake was a source for many of the articles, written by a then up-and-coming beat reporter named Siobhan Gorman. Drake allegedly reviewed drafts of Gorman’s work and assisted her by posing questions on her behalf to his unwitting colleagues. Without naming her sources, Gorman wrote in her articles that some of the information she’d received was classified.

Drake appears to have been one of Gorman’s primary sources for a string of exposés on the Trailblazer program, an NSA effort to collate massive amounts of electronic intelligence about terrorists and spies, which is a vital national-security mission. But Trailblazer had failed to live up to its designers’ promises, and the agency was wasting hundreds of millions of dollars.

Drake had been talking to a lot of people before he ever contacted Gorman. After NSA hired him in 2001, he began complaining to his superiors and to official watchdogs about wasteful programs. He followed the channels that employees are encouraged to use rather than seek out reporters. Drake went to inspectors general at NSA and the Defense Department as well as the congressional intelligence committees. According to the government’s indictment, Drake found a conduit to Gorman through a former House Intelligence Committee staffer named Diane Roark. She suggested that Drake get in contact with the reporter.

Drake knew NSA and its problems inside and out. He had been a contractor from 1991 until 2001, when the agency hired him as a permanent employee. A computer scientist, he’d spent most of his career honing a specialty in the field of “quality assurance,” a systematic approach to evaluating computer software to ensure that it’s functioning up to snuff. That put him in a position to know when programs weren’t performing as expected.

Drake was also a prolific writer. A survey of his work on quality assurance over the years reveals someone with a passion for precision and accountability as well as a certainty in the importance of his work. He jazzed up a number of dense papers for a trade conference with dramatic, occasionally allusive titles. “Testing Network Based Software Systems—The Future Frontier.” “The Future of Software Quality—Our Brave New World—Are We Ready?”

Drake fits the profile of a classic whistleblower. He was low enough in the bureaucracy to know how the place functioned day to day, but he had the high-level security clearances to obtain classified information that could support his allegations. Drake was tireless, driven, and obsessive. He may also have taken concerns about other NSA problems to another reporter. In April, at a journalism conference in Geneva, the New Yorker’s national-security writer, Seymour Hersh, said that Drake had contacted him two years before. Drake told a story “much more devastating” and “much more important” than what t

he Sun reported, Hersh said. But the reporter didn’t follow up—in part, he says, because he “didn’t like the situation” and the story was “very hard to prove.”

Hersh declines to elaborate or to discuss Drake. “The guy’s got enough problems,” he says via e-mail.

Gorman’s stories exposed a pattern of waste and poor decision-making at the top levels of an agency playing a front-line battle in the war on terror. She won a prize for her reporting. But nowhere in her long series did Gorman reveal how NSA spies on its targets or any information that could reasonably be expected to assist an enemy. Even former intelligence officials thought the articles revealed dire shortcomings that needed correction. One told me that an article showing that NSA was in danger of running out of electricity to power its computers came as a revelation. “I thought, you’ve got to be shitting me,” the former official said. “They’re Baltimore Gas & Electric’s biggest customer. How could they run out of power?”

But in the midst of her public-service journalism, Gorman may have put herself in legal jeopardy. Indeed, so do all reporters who knowingly publish classified information. Through her attorney, Gorman declined to speak with me. We have known each other for many years; I replaced Gorman as intelligence correspondent at National Journal in 2005 after she left the magazine to join the Sun. A source familiar with the case says Gorman hasn’t been contacted by the Justice Department.

The Drake case and the Risen subpoena represent two ends of a spectrum. In the Drake case, the government prosecuted an alleged leaker and left the reporter alone. In the Risen case, the government believes the reporter is essential to ensuring a conviction, so it has compelled him to give up his source.

Drake appears to have been discovered in the course of another investigation. NSA ran the program on electronic surveillance that Risen and Lichtblau exposed, and according to knowledgeable sources, Drake was being investigated as a possible source. In November 2007, the FBI raided his home in suburban Maryland. In the course of searching for evidence of one leak, about the surveillance program, the agents appear to have discovered evidence of another—the one to Gorman.

Drake resigned from NSA in April 2008 rather than be fired. In April of this year, he pleaded not guilty in US district court in Baltimore. After the hearing, Drake’s public defender, James Wyda, said: “There is no evidence that these allegations were motivated by disloyalty, greed, or any untoward motive.” Wyda had earlier told reporters that Drake was “extraordinarily cooperative” with investigators. The attorney said he was “very disappointed that the process ended in criminal charges.” A trial has been tentatively set for October 18.

Meanwhile, the fate of reporters may hang on two bills pending in Congress that would create a so-called shield for reporters to protect their sources’ identities. The bills would more or less enshrine the balancing test that many judges adopted after the Branzburg case in 1972.

The House bill is “particularly strong” on protecting sources’ anonymity, says Chuck Tobin. He explains that in order for a judge to enforce a subpoena, the government would have to show that the information that was leaked was “properly classified” to begin with, that the harm to national security was “significant and articulable,” and that the public interest in exposing the source’s identity “outweighs” the interest in protecting journalism.

“The judge would take each of these words very seriously,” Tobin says. “That would provide reporters like Risen with an excellent fighting chance to protect their sources—much better than the recent court decisions, which provide virtually no protection at all.”

Risen may not soon get the chance to use the press shield. As of early July, the bills hadn’t been put to a vote, and it looked doubtful that lawmakers would hold a vote before the August recess, particularly as they rushed to pass financial-services reform, confirm the next Supreme Court justice, and grapple with the faltering war in Afghanistan.

In negotiations with Obama-administration officials, reporters’ advocates tried to get a shield law with strong, unilateral protections for journalists—a true reporter’s privilege. “We found out fairly early on that was not going to fly,” says Paul Boyle, who runs public policy for the Newspaper Association of America. “Over time, the legislation has been weakened.”

In talking to members of Congress, Boyle found that even self-described defenders of the First Amendment weren’t prepared to give journalists total immunity from testifying. There had to be exceptions to assist law enforcement and to protect national security. “Most of the committee and staff are lawyers,” Boyle says. “They came from that bent.”

“The administration and the White House took more of a central role, along with the Justice Department, on what they could live with,” says Kurt Wimmer, a media attorney who was directly involved in the negotiations with the executive branch. “Justice can still issue subpoenas, but after the fact, having a judge review it was a hurdle.” Because some judges had tended to rule in favor of the government, prosecutors could be selective about where they issued their subpoenas. A press-shield law would even the playing field.

Wimmer thought “it was hard” for attorney general Holder to agree to the compromise. Holder’s former deputy, Washington attorney David Ogden, calls the press-shield bills “a major concession” and “unprecedented.”

“The government takes the idea of classified information very seriously,” Ogden says. “Certainly more seriously than the press does.” Ogden acknowledges that the government has a history of “some over-classifying over the years,” making information secret that didn’t need to be. “But when you’ve been in government, seeing classified information all the time, you know there are some very serious secrets that would harm national security if they were leaked.”

“The hardest issue has to do with limits,” Ogden says. “The Justice Department never supported an absolute reporter’s privilege.” Asked if there has been a sea change within the Justice Department after the Plame affair and if prosecutors are more aggressively pursuing leakers, Ogden says, “I don’t know. It’s a good question.”

Many journalists had been expecting a White House that would be friendlier to the press, one that, if not exactly tolerant of leaking, wouldn’t pursue leakers in court—and certainly wouldn’t go after reporters.

“With the Bush people, there were no illusions; with Obama there were high hopes,” says Mark Feldstein, the journalism professor who kept Jack Anderson’s papers from the FBI. “There was a lot of swooning in the media over Obama, and a lot of that translated into presumptions about policy. But the reality is that all administrations, all governments, view the press with skepticism if not paranoia. All governments want to control the agenda.”

To view the administration’s aggressive pursuit of leakers and journalists as an artifact of the current presidency, or as some kind of extension of Obama’s innate intolerance for airing private disagreements, is to miss the greater influenc

e that career government officials have over which cases to bring, and whom to subpoena.

“So much of the decision-making is made by the middle layers of the bureaucracy,” Feldstein says. “They function on autopilot. The career prosecutors don’t change from year to year. Their recommendations are probably the same whether Eric Holder is attorney general or Alberto Gonzales.”

The Justice Department is taking advantage of President Obama’s disdain for leaks by flexing a muscle that it’s been building for almost ten years as the tide has shifted from a protected press establishment toward a stronger prosecutorial force. Conveniently for Obama, the President has inherited a bureaucracy that’s primed for battle, and it’s winning more than it’s losing.

This story appears in the August issue of Washingtonian.