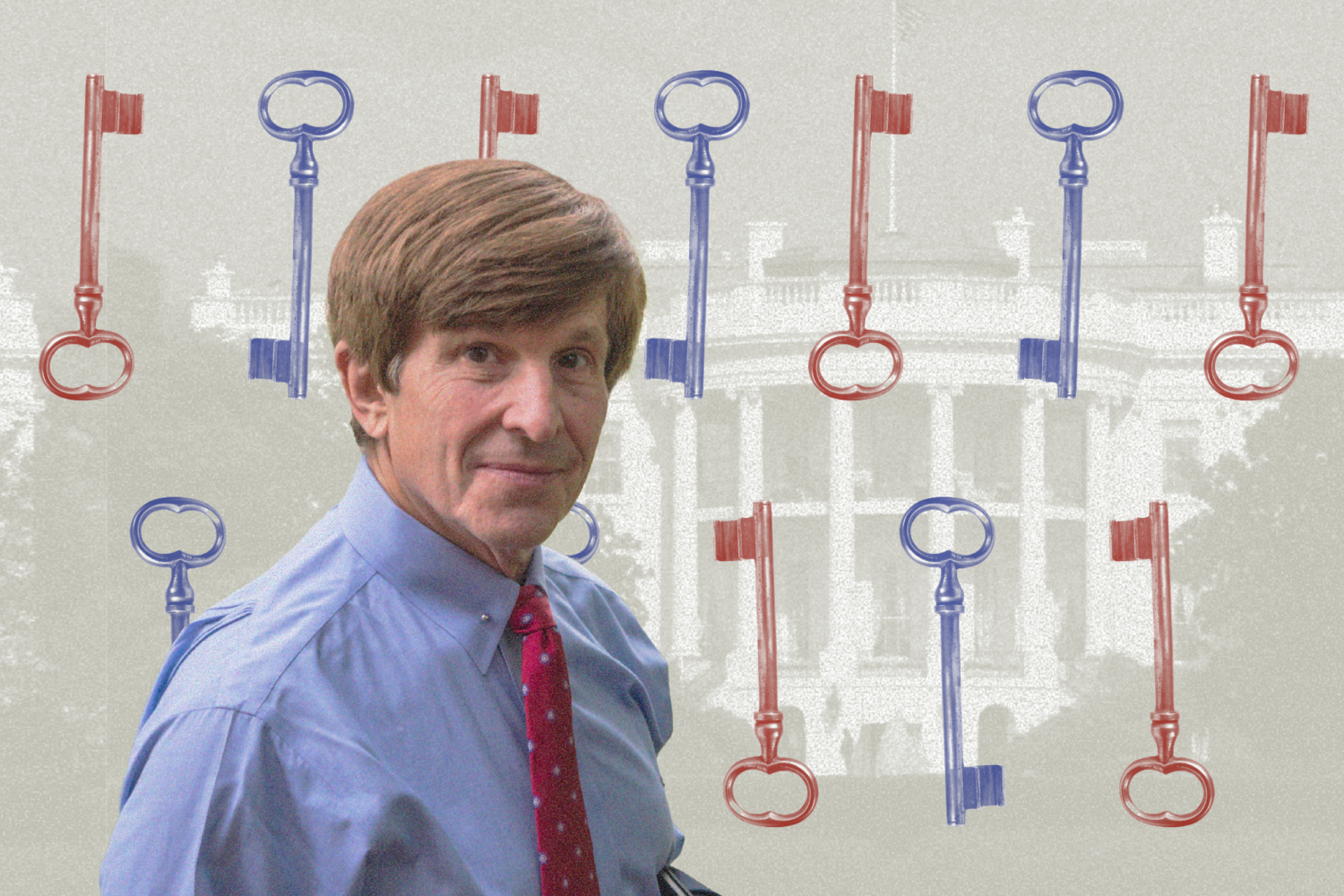

“It’s important to understand the many layers of a leader,” Jerrold Post says. “Not only what’s on the surface but what’s underneath—the man behind the mask—and how that shapes the leader’s behavior.”

For 21 years, Post worked in the CIA analyzing leaders. President Jimmy Car ter found his profiles of Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin critical to his Camp David peace talks.

Post was born in New Haven. His father managed a chain of movie theaters, and his mother was a bookkeeper. He attended Yale for undergraduate and medical school, then received postgraduate training in psychiatry at Harvard and the National Institute of Mental Health.

While in the CIA, Post founded the Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behavior. He’s now professor of psychiatry, political psychology, and international affairs and director of the political-psychology program at George Washington University.

He has written profiles of Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein, Hugo Chávez, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Kim Jong Il, among others. In 1990, he testified before Congress on his political-personality profile of Saddam Hussein. Since 9/11, he has testified on terrorist psychology before Congress and the United Nations and has been an expert witness in five terrorist trials.

He is author, coauthor, or editor of eight books, including Leaders and Their Followers in a Dangerous World: The Psychology of Political Behavior. His newest, The Mind of the Terrorist: The Psychology of Terrorism From the IRA to Al Qaeda, will be published in December.

Post’s wife, Carolyn, is an advocate for people with disabilities and serves on the board of two nonprofit corporations and a foundation serving people with disabilities. They have three daughters—Cindy is a clinical psychologist, Meredith works in special education, and Kirsten works for the Consumer Product Safety Commission—and five grandchildren.

In Bethesda, where Post lives and sees patients in private practice, we talked about what he’s learned.

What kind of people go into politics?

While there are many politicians who enter politics to make a difference, the first sentence in my next book will be “If we were to subtract from the ranks of world leaders those politicians who had significant narcissistic personality features, the ranks would be perilously impoverished.”

There’s something about being onstage, having adoring followers, that’s fuel for the insatiable ego; it’s intoxicating.

Take Fidel Castro, who thrives on the roar of the crowd. He’d give eight-hour perorations. His audience would be dropping of exhaustion, but he’d be getting stronger. Fidel felt a chemical connection with his audience.

He was illegitimate at birth and had a troubled childhood. The acclaim of being “father of the country” helped compensate for what he lacked growing up.

The psychologically balanced person takes internal satisfaction from his accomplishments and isn’t consumed with outside adoration.

What do you examine when judging a political leader?

I combine a longitudinal psychobiography with a cross-sectional analysis of his political personality and leadership. His relationship with his leadership circle is critical. A leader in touch with reality psychologically can be out of touch with reality politically; that happens if he’s surrounded by sycophants.

In 1960, President Kennedy told his new Cabinet appointees, “I want you to criticize me. I want your best ideas.” He wanted “the best and the brightest.”

Contrast that with Saddam Hussein, who was surrounded by people who told him what he wanted to hear, not what he needed to hear, and were afraid—for good reason—to offer constructive criticism.

Here’s a telling episode from 1982, when the war Saddam had launched against Iran was going badly, with missiles raining down on Baghdad. In desperation, he offered a cease-fire to Iran’s leader, Khomeini, who replied that Saddam first had to step down as president of Iraq.

Saddam called a meeting of Cabinet members and asked for their opinion. They were unanimous—“Saddam is Iraq, Iraq is Saddam. You must stay on, most noble president.”

He then insisted they give their frank, candid, and creative suggestions. Most didn’t, but his minister of health, an Oxford-educated physician, politely offered, “Well, you might consider stepping down temporarily until our goal of peace is achieved, and then resume the presidency.” A clever suggestion.

Saddam thanked him and had him arrested. The minister’s wife went to Saddam that night. Her husband, she pleaded, had always been loyal to him. She begged Saddam to return her husband to her.

Saddam seemed touched and promised to do so. The next day he did—the only promise he ever kept, as best I could tell. He returned her husband—in a black canvas bag, chopped into pieces.

This incident powerfully concentrated the attention of the other ministers, who to a man agreed Saddam must stay on as president. The war went on for another six bloody years.

I also judge a leader by his staff’s caliber, background, diversity, and flexibility. How good are they at changing their minds when new information comes in—and how good is he at it? How quickly will he decide? Some people resist making any decision until all the data are in. This can be disastrous, as it leads to procrastination.

Any crisis will be ambiguous, without anywhere near a full range of information. Nevertheless, decisions must be made.

Some leaders—such as Anwar Sadat and Mikhail Gorbachev—change everything when they get to the top. Does that impress you?

In his book The Hero in History, the philosopher Sidney Hook makes a critical distinction between “eventful” and “event-making” heroes.

The eventful leader reacts to a momentous event—a fork in the road of history—in an innovative, heroic fashion. Take George H.W. Bush: When Saddam invaded Kuwait, he used his international knowledge and connections to pull together an amazing global coalition.

In contrast, the event-making leader doesn’t come upon a fork in the road—he makes it. From that perspective, Hitler and Osama bin Laden were event-making.

Some leaders are both. Thomas Jefferson’s role in drafting the Declaration of Independence was impressive; he had an eloquent way with prose. Yet someone else could have drafted that document, and many others helped him do so. That was “eventful.”

Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase was event-making. It changed the nature of our country and was accomplished against overwhelming odds. He had a vision and pursued it against great difficulty. It was a remarkable achievement.

How do you predict whether a leader will perform well?

In profiling a world leader, I try to discern his careerlong pattern of leadership and decision-making. I pay particular attention to first successes and first failures. Most official intelligence emphasizes what’s happening right now. I look back—knowing that if something scarred the leader in the past, he’ll avoid it in the future—and try to identify the issues that “hook” his political personality.

Stalin had a brutalizing father and attended a harsh Orthodox seminary. No books besides religious texts were allowed. So he rebelled as an adolescent by smuggling in the writings of Marx and Lenin. He made Lenin into an idol, almost a god. Just as he had been brutalized as a boy, he was brutal to his people as Soviet leader. He was a role model for Saddam Hussein.

In delving into childhood experiences, I look at the person’s dreams. Anwar Sadat had dreamed of greatness ever since he was a teenager, when he was fascinated by Gandhi. Sadat would go out to the desert and fast, wrapped in a sheet and accompanied by his goat. When he made his remarkable crossing of the Jordan into Jerusalem, he was fulfilling a larger-than-life image he’d long held.

A leader’s damaged personality can do a lot of damage to his society.

To be sure. Mao Zedong’s name will be engraved in the pantheon of charismatic leaders, but his excesses in the Great Leap Forward, and especially the Cultural Revolution, derived from his insatiable narcissism, his dreams of glory. His urgency to solidify the revolution before he died led to intemperate excesses—the loss of a whole generation.

In contrast, Zhou Enlai, who was always by Mao’s side, was very mature psychologically. He devoted his final years to moderating Mao’s excesses. Even while dying of stomach cancer, he didn’t allow his own misery to distort his judgment.

Just as narcissistic as Mao was Saddam Hussein, surely the most traumatized leader I’ve ever analyzed.

Saddam’s father and brother died while his mother was pregnant with him. With these two deaths, his mother became so depressed that she tried to kill herself, then to abort her fetus.

Both attempts were failures. At Saddam’s birth, she wouldn’t even look at her newborn son—she didn’t want him. So he lived for his first 2½ years with an uncle. Then his mother remarried, but her new husband was physically and psychologically abusive to young Saddam.

It’s hard to imagine a worse start to life. It produced a “wounded self.” But at age eight, Saddam returned to his uncle, who filled him with dreams of glory: Someday he’d be a historic hero to all Arabs. He’d follow the path of Saladin or Nebuchadnezzar.

Saddam’s dreams went unfulfilled until the summer of 1990, when Iraq invaded Kuwait. Saddam became topic number one around the world. When he would make a bellicose grunt, oil prices would jump $20 a barrel. He had the world by the throat. At last he was recognized as a world-class leader—his dreams of glory achieved.

The layers in his personality were symbolized by his residences. He was born in a mud hut, reflecting the psychological poverty at his core. His grandiose dreams were reflected in his many palaces. But look at what was beneath them—bunkers bristling with weapons. Underneath the grandiose façade was the siege mentality. He was always suspicious of being betrayed. And then, irony of ironies, at the end he was found by US soldiers in a hole beneath a mud hut.

How do you know these things?

From biographies, interviews with officials who have dealt with the leaders, and systematic analysis of leadership and decision-making. Ninety to 95 percent of my assessment work in the CIA came from open sources.

This field of political profiling got a big boost when we prepared Jimmy Carter for the Camp David talks. He needed psychological profiles of Sadat and Begin because he wanted to understand who he was dealing with. We did three for him. The third, concerned with how these two very different personalities would interact, was the most important.

We concluded that their minds worked totally differently. Sadat’s big-picture mentality contrasted directly with that of the detail-minded lawyer Begin. So even if they agreed, they’d be talking past each other. Hence it was critical for Carter to play an intermediary role—and minimize their direct time together.

Do your methods apply to nonpolitical situations?

I’ve consulted with corporations engaged in high-level negotiations. They may need to understand an opposing CEO—what shaped that person, key values, negotiating techniques, how much he kept his word in the past.

Despite the value of such profiles, we still can never predict precisely, only identify patterns. There are many variables in any negotiation or crisis situation. We can only say that, other things being equal, in this type of situation this type of person will behave in this manner.

We sometimes see surprising behavior from a leader, leaving us wondering, “What’s going on?” Sometimes that indicates serious medical illness, which is critical to know but usually hard to find out.

Dwight Eisenhower had two major illnesses. In addition to his well-publicized heart attack, with which the public was sympathetic, he had a stroke, which affected his ability to communicate clearly; it was not well publicized. The public wants a wise, decisive, clear-thinking leader, and the stroke threatened that image.

Important to us today is the case of the Shah of Iran. His fall has caused us untold misery over the past 30 years.

In the late 1970s, the intelligence community was castigated for insufficiently attending to Khomeini and the rise of radical Islam. But the main intelligence failure was not knowing that the Shah was dying.

We now know that in 1973 the Shah was losing weight and feeling lousy. His French physicians secretly diagnosed him with a preleukemia illness. Until then, the Shah had been a wise leader. He had used force when he needed to yet had been conciliatory when he needed to be. He wrote a remarkable book, Mission for My Country, which spelled out his goals for modernizing Iran over the next 20 to 25 years.

Once his physicians warned him that he had only another six or seven years to live, he superimposed his personal timetable on his political timetable, driven to accomplish his goals before he died. So the Shah quadrupled oil prices, pouring money into Iran despite its poorly prepared infrastructure. This rush led to a revolution of rising expectations and social dislocations, which destabilized Iran and paved the way for Khomeini.

How do you apply this psychological approach to the current US presidential candidates?

I can’t comment on individual American politicians. It violates the American Psychiatric Association’s code of ethics to provide a public diagnosis of a figure without having interviewed that person.

But let me observe that a presidential campaign, like the one we’re now watching, is an exercise in applied political psychology. It’s a contest of dueling frames of reference. It’s the voting public’s task, and a tough one, to discern who this candidate really is—what his or her core attitudes and goals are beneath the well-spun exterior.

Is yours a new field?

Relatively new. Its modern incarnation dates back to Harold Lasswell, who in 1930 wrote Psychopathology and Politics, about the drive for power among leaders.

Eric Erikson is one of my heroes. Freud examined the individual within the family, while Erikson located the individual within the society. He took the first hard look at the life cycle, coining the phrase “identity crisis,” referring to the period between adolescence and young adulthood.

Erikson observed that political identity jelled at the same time as psychological identity. The first North Vietnamese leaders spent their teenage years in prison, making them hardcore revolutionaries. Nothing converts a youthful adventurer into a terrorist revolutionary more than prison.

But I consider the real founding father of political psychology to be William Shakespeare, whose political personality profiles of such leaders as Richard III, King Lear, and Macbeth were remarkably insightful.

Your lesson of life?

Freud said it best: lieben und arbeiten—to love and to work. To find the balance between warm, loving relationships while achieving professional ambitions. When you put the two pieces together, you’ve got yourself a splendid life.