In May 2001, Dr. Thomas Novotny, assistant surgeon general of the United States, was in Geneva negotiating a global treaty on tobacco control when he got a late-night telephone call from Washington.

William Steiger, then an adviser to Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson, ordered Novotny to abandon positions on international tobacco control that had been staked out by US negotiators during the Clinton administration.

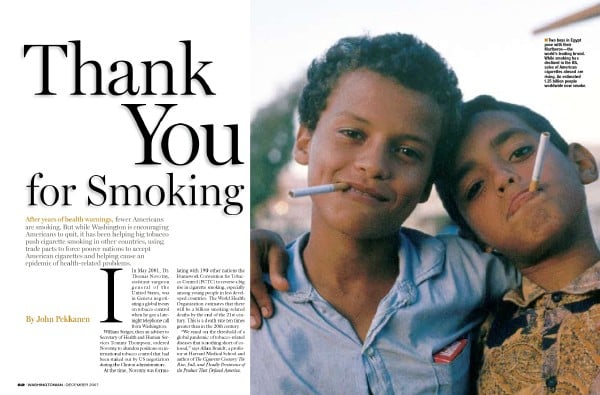

At the time, Novotny was formulating with 190 other nations the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC) to reverse a big rise in cigarette smoking, especially among young people in less developed countries. The World Health Organization estimates that there will be a billion smoking-related deaths by the end of the 21st century. This is a death rate ten times greater than in the 20th century.

“We stand on the threshold of a global pandemic of tobacco-related diseases that is nothing short of colossal,” says Allan Brandt, a professor at Harvard Medical School and author of The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America.

Washington has helped fuel these soaring smoking rates. Global trade agreements allowed American cigarette companies, aided by Congress and four administrations—Republican and Democratic—to force open the doors of developing countries to American cigarette exports in the 1980s and 1990s.

To sell billions of cigarettes overseas, the tobacco industry used the marketing techniques that had been so successful in the United States. And it displayed a total disregard for the health consequences of exporting and promoting tobacco to the young and poor around the world.

“The message I got that night came straight from the White House,” Novotny says. “Steiger said we now had to ‘bracket’ language in the FCTC negotiations that we had previously supported, meaning we would not commit to it anymore. The US also reserved the right to opt out of our previously held positions such as support for mandatory cigarette taxes and clean-indoor-air policies as well as restrictions on cigarette advertising—strategies we know can reduce cigarette smoking.

“Other countries had looked to us for leadership because we had developed a number of successful antismoking strategies,” Novotny says. “Suddenly backing away from this and retreating on our earlier commitments was devastating to me and an embarrassment for the US, but Steiger wasn’t apologetic. He was an ideologue there to do the administration’s bidding.”

The demands Steiger related to Novotny had been spelled out in a 32-page memo prepared by Philip Morris and dated March 15, six weeks before Steiger’s late-night call. The world’s biggest multinational tobacco company, Philip Morris had sought changes to weaken the FCTC treaty. It asked that health warnings not “dominate” cigarette packages because they could “gratuitously infringe upon our trademarks.” The Bush administration went along with 10 of the 11 changes requested.

Did big tobacco dictate the US position on an international treaty? The White House refused congressional requests for information regarding meetings between government officials and Philip Morris concerning the FCTC treaty.

Philip Morris claimed that the timing of its 32-page memo and the US pullback was coincidental. David Greenberg, the company’s international senior vice president for corporate affairs, said at the time that Philip Morris was “ready to embrace regulation around the world.”

The tobacco industry wields lots of political power because it saturates the political process with money. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the industry gave more than $7 million to President Bush and other Republicans during the 2000 election cycle. It gave $1.4 million to Democrats during the same period.

Philip Morris contributed $100,000 to Bush’s inaugural celebration and $800,000 more to the Republican Party after the election. The company gave another $57,767 to the Republican Party one week before the start of the FCTC’s second round of negotiations.

Philip Morris had a strong ally in the White House: Karl Rove, deputy chief of staff until his recent resignation, had been on the cigarette maker’s payroll as a consultant from 1991 to 1996, including a period while he was working for then–Texas governor George W. Bush.

Novotny had known since the FCTC negotiations began in earnest in 1999 that opposition would be formidable. He walked a tightrope between the treaty’s public-health supporters and the opposition forces. At public meetings in Washington and San Francisco, the tobacco industry and its advocates made clear their opposition to many FCTC provisions.

During the latter part of the Clinton administration, Novotny had been summoned four times to the Capitol Hill office of Senator Jesse Helms to meet with his staff. Helms, a Republican from North Carolina, was a supporter of the tobacco industry. As chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he would wield power over the FCTC treaty if and when it came to the Senate for ratification, a point that Helms’s aides drove home.

At one meeting, a Helms aide warned: “We’re watching you, Dr. Novotny.”

Says Novotny: “They were merciless.”

Two weeks after the late-night call from Steiger, Novotny had had enough. He met with Secretary Thompson and tendered his resignation.

When Thompson later appeared on CNN, Robert Novak asked him if Novotny had resigned because the Bush tobacco policy had been “too soft.”

“What kind of message does that send to the world,” Novak asked, “that the United States is backing away from the tobacco question?”

As Wisconsin governor, according to the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, Thompson had accepted nearly $100,000 in political contributions from tobacco interests, including Philip Morris, whose corporate holdings include Wisconsin-based Miller Brewing Company and Oscar Mayer Foods. He also went on junkets to Australia, Africa, and England with Philip Morris executives.

“I really think that your facts are a little bit erroneous,” Thompson told Novak. “I’ve talked to Tom Novotny on many occasions. He’s a good friend. He’s a valued member of the administration. And he is retiring not because of the tobacco policy: He’s retiring because he’s reached retirement age and he wants to slow down. And he’s going to retire in February.”

“Nonsense,” Novotny says, noting that Thompson has never been a friend, much less a good friend.

“I was 54 at the time and dedicated to a career in public service,” says Novotny, a medical doctor and a retired commissioned officer of the US Public Health Service. “Leaving when I did cost me a lot in terms of professional opportunities, but there was no way I could stay.”

Novotny is now professor of epidemiology at the University of California at San Francisco and director of international programs at the university’s School of Medicine, where he’s involved in tobacco research, control, and education.

Novotny and other public-health officials feel an urgency about tobacco control because they see what is unfolding. An estimated 1.25 billion people smoke worldwide, more than ever before, according to the Tobacco Atlas, published by the American Cancer Society with support from the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the International Union Against Cancer.

Eighty percent of smokers now live in less developed countries, a shift in smoking patterns. Between 1970 and 1995, per-capita cigarette consumption in poorer developing countries increased by 67 percent while it dropped by 10 percent in the richer developed world.

WHO estimates that 700 million children are exposed to secondhand smoke, and every day another 80,000 to 100,000 people—many of them children and adolescents in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe—begin smoking. By 2030, WHO forecasts that 10 million people a year will die of smoking-related illness, making it the single biggest cause of death worldwide. The largest increase will be among women, and seven of every ten smoking deaths will occur in developing countries already overburdened with AIDS, malaria, poor sanitary conditions, and other public-health challenges.

“We are just seeing the tip of the iceberg of tobacco’s devastating impact on low-income countries around the world that can least afford to deal with the rising incidence of lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and increased risk to pregnant women,” says Matthew Myers, president of the Washington-based Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

“Even though the US has been one of the world’s most progressive public-health leaders,” Myers says, “our government’s complicity in exporting tobacco products around the world means in all likelihood that despite our many good works, our net impact on the world’s health is a negative.”

“If you look at countries in Africa where there is the greatest collection of poverty,” says former surgeon general C. Everett Koop, now 91 and senior scholar at the Koop Institute at Dartmouth College, “and you add the slow deaths from tobacco to the more rapid deaths from AIDS and other infectious disease, you effectively eliminate the people who are the backbone of the workforce. This will be disastrous for those countries.”

A World Health Organization report notes that tobacco use worsens malnutrition and literacy rates in developing countries because poor families spend as much as 10 percent of their expenses on tobacco—meaning less for food and education.

Western cigarettes are enticing to many people in poorer countries because smoking is regarded as a status symbol, a fact tobacco companies emphasize in their advertising. Following its philosophy that today’s teenager may be tomorrow’s customer, the tobacco industry targets young people in ads. Marlboro T-shirts in children’s sizes have been found in Africa, where children often begin to smoke before age ten. In Kenya, a recent survey found that 13 percent of primary-school children abuse tobacco.

Cigarette ads have been placed near schools, and free cigarettes are handed out at rock concerts, discos, sporting events, and other places where young people gather. In some countries, cigarettes are sold not just by the pack but also by the single cigarette to the very young.

US tobacco exports find their way into Iran despite the Bush administration’s economic sanctions against that country. Allowed in as agricultural products, US tobacco exports to Iran totaled $50 million in 2005, making cigarettes the largest American export to that country.

“The chicanery of the tobacco industry is something you almost have to admire,” says Dr. Koop. “They are ahead of us at every turn, and they have enormous resources. At the time we were producing the annual surgeon general’s report on smoking at a cost of $1 million, the cigarette industry was spending $7 billion saying the surgeon general was wrong. It’s like using a muzzle-loading musket against a machine gun.”

As the FCTC negotiations in Geneva continued in the two years after Novotny’s resignation, US negotiators objected to a proposed ban on tobacco advertising on the grounds that it violated free speech.

Industry representatives attacked the FCTC efforts to curtail smoking as condescending—calling it an attempt by the industrialized West to decide what was best for less developed countries and describing it as a form of cultural imperialism.

“Imposing Western priorities, or ‘global solutions’ that force the values and priorities of any one country on another, can become a new form of colonialism,” said a statement issued by British American Tobacco, which owns Brown & Williamson, a US subsidiary that sells Kool, Lucky Strike, and other brands.

Antitobacco organizations observing the negotiations in Geneva concluded that the United States was doing more harm than good. John Seffrin, head of the American Cancer Society, called the US positions on the FCTC treaty “unconscionable.”

In May 2004, three years after Novotny’s resignation, HHS secretary Tommy Thompson signed the FCTC treaty on behalf of the United States at the World Health Assembly in Geneva.

“President Bush and I look forward to working with the WHO and other member nations to implement this agreement,” Thompson said.

In the three-plus years since then, the White House has yet to send the FCTC treaty to the Senate for ratification.

“Thompson got approval to sign it because he didn’t want to show up at the Geneva health assembly and get booed,” Novotny says. “It was an easy out because it was never going to go anywhere in the Bush administration.”

The administration says the treaty is under study by the State Department.

To date, 168 countries have signed the FCTC and more than 150 countries have ratified it. In February 2005, without US ratification, it became the world’s first international public-health treaty. Among the measures endorsed by the treaty are bans on tobacco advertising and on the distribution of free cigarettes to young people. It calls on countries to prohibit misleading terms such as “light,” “low tar,” and “mild” and to require health warnings on tobacco packages. It contains stronger provisions than the tobacco industry and the Bush administration wanted but weaker ones than public-health experts advocated.

The United States’ failure to ratify the FCTC means the US government no longer will have a place at the table in future FCTC negotiations or any say in the treaty’s implementation. A number of countries reportedly prefer this state of affairs because they’ve come to regard the United States as seeking to weaken the treaty.

In The Cigarette Century, Allan Brandt links the push to export cigarettes in the 1980s with the increasing number of Americans who quit smoking. The number of adult smokers in the United States dropped from 46 percent of the adult population in 1950 to less than 35 percent in 1985.

The big tobacco companies knew that the trend would continue, and they were right. By 2004, the figure had fallen to 21 percent. Between 1975 and 1994, US tobacco sales declined from 607 billion to 486 billion cigarettes a year, and they’ve continued to decline.

During those same 20 years, overall sales of American cigarettes rose by 11 percent because of cigarette exports by the three major US tobacco companies—Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, and Brown & Williamson. In 1983, 40 percent of the combined sales of R.J. Reynolds and Philip Morris were outside the United States. By 1993, the figure was 65 percent.

Big tobacco’s most powerful and faithful export ally has been the US government. By threatening trade sanctions, the United States leveraged international-trade agreements to force US tobacco products into foreign markets in the name of “fairness in trade.” According to Brandt, the Reagan administration viewed tobacco exports as a way to alleviate a worsening trade deficit that reached $123 billion in 1984.

Despite putting up some resistance, Thailand, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea were opened to American cigarettes.

Clayton Yeutter, US trade representative from 1985 to 1989 and the Reagan administration’s point man, explains: “This was totally about trade, and it didn’t matter whether it involved tobacco or automobiles or semiconductors. The issue was that a number of countries had tobacco policies that were blatantly discriminatory. They sold their own tobacco products in their country but prevented us or anyone else from selling them. They were in violation of World Trade Organization rules, and this constituted unfair trade practices. We told them, ‘Either fix this or we will take action against you for unfair trade practices under Section 301 of the Trade Act.’ ”

A nonsmoker, Yeutter says he has no love for the tobacco industry: “It’s an industry that could happily disappear off the face of the earth.” Nonetheless, he says the United States needed to send the world a message that it would no longer tolerate practices that were in violation of global-trade agreements.

Speaking out forcefully against the increasing cigarette exports was Dr. Koop.

“At a time when we are pleading with foreign governments to stop the export of cocaine,” he said in 1989, “it is the height of hypocrisy for the United States to export tobacco.”

Koop’s message went unheeded, and the public-health community was frozen out of the tobacco-export discussion.

Yeutter says the discussion was over trade issues, not public health. And he says neither he nor the US government bears any responsibility for the public-health consequences of increased cigarette smoking worldwide.

Yeutter later served as secretary of Agriculture and chair of the Republican National Committee. After leaving government service, he joined the board of the multinational corporation British American Tobacco. (He no longer serves on the board.) He is now senior adviser for international trade at the DC law firm Hogan & Hartson, which along with WilmerHale and Zuckerman Spaeder is among a handful of DC law firms that do not represent tobacco interests.

Carla Hills, who declined to be interviewed for this article, succeeded Yeutter as US trade representative in 1989 and followed the same path. She pressed the tobacco industry’s claims against Thailand by arguing that the purpose of Thailand’s ban on US cigarette exports was to protect the country’s state-run cigarette monopoly, not to reduce smoking.

“The tobacco industry very shrewdly utilized the mechanism of the US trade representative to open these new markets,” says Allan Brandt. In 1981, Brown & Williamson, R.J. Reynolds, and Philip Morris formed a nonprofit industry trade group called the Cigarette Export Association. The CEA, Brandt says, “put a very heavy hand on the US trade representative to act in their interest, and both Yeutter and Hills became very effective advocates for the globalization of tobacco use.”

Big tobacco also brought in heavy hitters. In 1985, Philip Morris hired the late Michael Deaver, who had resigned as Reagan’s deputy chief of staff earlier that year, to persuade South Korea to open its doors to American cigarettes. In a 1987 trial in which Deaver was convicted of lying to Congress about his lobbying activities, testimony revealed that he’d been paid $250,000 to use his “political influence” on behalf of the tobacco company. Testimony also disclosed that Philip Morris had turned to Deaver to counter Reagan’s former national-security adviser, Richard Allen, who had gone to South Korea on behalf of R.J. Reynolds.

Members of Congress likewise helped tobacco interests. In the summer of 1986, 13 tobacco-state senators wrote to President Reagan arguing that “retaliation” was the only option for convincing Japan to accept American tobacco products, according to a report published in Multinational Monitor in 1987 by Gregory Connolly, then head of the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program and now a professor at the Harvard School of Public Health.

A July 1986 letter from Senator Jesse Helms to Japanese prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone noted that American cigarette sales amounted to less than 2 percent of the Japanese market: “Your friends in Congress will have a better chance to stem the tide of anti-Japanese trade sentiment if and when they can cite tangible examples of your doors being opened to American products.” Helms suggested that US cigarette sales attain 20 percent of the Japanese market within 18 months.

Connolly also reported that Senators Christopher Dodd, Robert Dole, Robert Kasten, and Lowell Weicker pressed Hong Kong not to pass a pending public-health law that would prohibit the introduction of smokeless tobacco by the US Tobacco Company, headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut. Hong Kong had no history of smokeless tobacco, and officials there considered it to be a health risk.

“We believe such action would constitute an unfair and discriminatory restriction on foreign trade,” the senators wrote, using terms that suggested future trade sanctions. The US Tobacco Company contributed $26,000 to the election campaigns of the four senators in 1986.

The bandwagon promoting US tobacco exports continued during the George H.W. Bush administration. In a somewhat convoluted remark to a North Carolina audience in 1990, Vice President Dan Quayle said: “Tobacco exports should be expanded aggressively because Americans are smoking less. . . . We’re not going to back away from what public-health officials say and what reports say. But on the other hand, we’re not going to deny a country an export from our country because of that policy.” Then-secretary of Agriculture Yeutter declared the sharp rise in tobacco exports to be “a marvelous success story.”

It was never a fair fight. Says Dr. Koop: “We swing a big stick. To threaten a small or poor country with more poverty through trade sanctions just to sell cigarettes is such an obviously lousy thing to do.”

What couldn’t be accomplished legally was sometimes accomplished illegally: Cigarette smuggling became an international enterprise in which billions of cigarettes were smuggled throughout the world, often into countries that did not yet allow in exports.

Cigarette companies have repeatedly denied involvement in the smuggling. But the Center for Public Integrity reported in 2000 that internal documents from the British American Tobacco company implicated senior BAT executives in smuggling to about 30 sub-Saharan African countries from the late 1970s into the 1990s.

David Sweanor, a professor of law at the University of Ottawa and a longtime anti-smoking advocate, began helping investigate cigarette smuggling in the 1980s.

“It was very clear many major tobacco companies were significantly involved in tobacco smuggling,” Sweanor says. “They would ship cigarettes to nonexistent markets where they knew these cigarettes would go out to illicit markets. Take Andorra, a tiny country in the Pyrenees between Spain and France. In the early 1990s, there were huge cigarette shipments from various countries to Andorra. Even if every man, woman, and child there smoked incessantly and didn’t take time to sleep, they couldn’t have smoked them all. Andorra wasn’t a big country for smoking, but it was for smuggling.”

In a paper published in the journal Tobacco Control in 1998, Luk Joossens, a Belgian sociologist long involved in tobacco control, concluded that for the year 1996, 355 million cigarettes—about a third of the world’s exports—were missing and presumed smuggled.

“There was much to be gained from smuggling,” Sweanor explains. “Cigarette companies could sell more product than they otherwise could through these illicit channels. In many developing countries, cigarette smuggling was a very effective way to open markets that they could not gain access to. You would find Western brands in Vietnam despite the fact that they were not allowed in the country.”

Sweanor and others have discovered that money from cigarette smuggling has at times found its way into terrorist organizations. Although cigarette smuggling has declined, Sweanor says it remains prevalent worldwide; he estimates at least 5 to 6 percent of the cigarette trade is illicit.

In the summer of 2000, before leaving on assignment to the World Health Organization in Geneva, Dr. Michael Eriksen, director of the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health from 1992 to 2000, was ordered to recuse himself from any involvement in the FCTC negotiations.

“It was the most bizarre thing I’ve ever been a party to,” says Eriksen, now director of the Institute of Public Health at Georgia State University and an authority on tobacco-control issues. “You would assume our government would want someone with expertise in the area of tobacco control to represent the US in negotiations on a treaty to control cigarette smoking worldwide.”

Part of the surprise was that Eriksen knew he had the support of President Clinton, a critic of tobacco use. The Clinton administration wanted public-health officials taking part in the tobacco-export debate, something that had been lacking in earlier administrations.

Yet to Eriksen’s astonishment, here was the State Department telling him, a high-ranking member of another agency, that he could not take part in an important meeting involving his area of expertise.

Eriksen asked why he had to recuse himself. He was told there were concerns that he might reveal internal strategy of the US position on the FCTC to the World Health Organization because he’d previously been involved in tobacco-control negotiations. The tortured logic seemed to be “because you’re an expert in this, we can no longer let you be involved in it.”

It got stranger. John Sandage, an attorney in the State Department’s Office of Legal Advisor and US representative on the FCTC negotiating team, ordered Eriksen to put his recusal in writing.

“I was told if I did not formally recuse myself, I would not be allowed into Switzerland,” Eriksen says. He did so.

“Any travel to a foreign country by a government employee on official business must be approved by the US embassy in that country,” Eriksen explains. “I told a friend before I left that I wasn’t sure when I arrived in Geneva whether I’d be greeted or arrested, and it wasn’t a joke,” he says. A half hour before he was to leave for the airport, Eriksen was cleared to go.

Once in Geneva, he worked on health promotion generally and sat quietly in the observer area during some of the FCTC proceedings. When State Department officials spotted him there, they registered a complaint with the Department of Health and Human Services, Eriksen’s parent agency, asking that he not be allowed to observe.

“It was just so absurd,” he says. “I was in a public area and they couldn’t tell me I could not observe, so of course I didn’t stop. I am an American citizen, after all.”

In the way it often gains favor, the tobacco industry had contributed $1.2 million in the 1980s to renovate the State Department’s historic Treaty Room. A framed commemoration in the suite acknowledges the “generous contributions” of Philip Morris USA, R.J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, Lorillard, United States Tobacco, American Tobacco Company, and Liggett & Myers. Among the room’s 18th-century antiques and crystal chandeliers are moldings carved in the shape of tobacco leaves, blossoms, and seed pods.

Eriksen believes that the State Department threw up roadblocks to protect its turf, not to repay an old favor from the cigarette industry.

“The State Department was very wary of HHS involvement with the FCTC treaty because they consider treaties of any kind to be under their control, and they did not want to cede that control,” Eriksen says.

His experience exemplified the double message that emanated from the Clinton administration on tobacco exports. On one the hand were public proclamations on the dangers of smoking, on the other a turf war between the public-health community and officials of the Commerce and State departments.

“We had great support from different agencies of the federal government and direction from the White House to go forward to make the FCTC a real health treaty based on research and science,” Novotny recalls, “and many members of the scientific and tobacco-control community were involved with FCTC. But I didn’t know at the time that some members of the FCTC delegation from the Commerce Department were apparently meeting on the side with the tobacco industry, and there were also lobbyists from the cigarette industry trying to get to the State Department.”

The Clinton administration worked at cross-purposes in other areas. At the same time that it was seeking to place cigarettes under the control of the Food and Drug Administration, it was insisting in bilateral trade talks that China allow more US tobacco into the country.

Clinton backed a tobacco-subsidy bill in 2000 to give American tobacco companies an estimated $100 million in annual tax breaks for exported tobacco products. Democratic representative Lloyd Doggett of Texas, one of the most vocal anti smoking advocates in Congress, said support for the subsidy bill was “a very difficult position for the administration to explain.”

“Clinton tried to have it both ways,” Doggett says. “There were times when the Clinton administration was making pledges to me about steps they would take on international tobacco exports at the same time they were making pledges to people from North Carolina that were opposite of what they were telling me.”

Doggett had sponsored an amendment banning the use of monies from the Commerce, Justice, and State departments to promote the sale or export of tobacco overseas. US embassies had been helpful to tobacco interests during the Reagan and Bush administrations, and Doggett says he’d learned that Clinton appointees in the US embassy in Thailand were trying to interfere with Thai public-health regulations that discouraged smoking.

Though weakened by tobacco interests, Doggett’s amendment passed in 1997, and the next year the Clinton administration issued an executive order to US embassies implementing the law.

Speaking in support of the amendment, Arizona senator John McCain said, “It bothers me that we want to stop American kids from smoking, yet we don’t seem to have the same degree of concern about Asian or African kids.”

The Bush administration has not sought to rescind the order implementing the Doggett amendment. After reviewing more than 800 pages of message traffic between government agencies and US embassies, Doggett concludes that it is having a “modest effect” in lessening government help to tobacco companies overseas.

If the United States led the way in selling cigarettes to less developed countries, other developed nations have jumped on the cigarette-export bandwagon. Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands are all involved in cigarette exports to less developed countries. Japan once complained bitterly about American cigarette exports, but Japan Tobacco, which is partially owned by the Japanese government, bought R.J. Reynolds’s foreign tobacco operations in 1999 and has become the world’s third-largest cigarette exporter. It has also been less than cooperative with the FCTC treaty.

Philip Morris, the world’s biggest transnational tobacco company, reportedly had cigarette sales of more than $64 billion in 2006. For the same year, British American Tobacco exceeded $20 billion in cigarette sales.

Headquartered in London, BAT owns the brands Lucky Strike, Kent, Kool, and Benson & Hedges, among others. Philip Morris, now a division of Altria Group, owns Marlboro, the world’s leading brand. Together, the three leading tobacco-exporting companies—Japan Tobacco is the third—exceed $120 billion in annual cigarette sales.

“I do find it appalling that so many Western countries are doing this,” Allan Brandt says. “There is a kind of libertarian, individualist ethic that is a rationalization for immoral behavior at the corporate and governmental level. In the end, they say it’s a legal product and everyone can make their own decision—an argument in their self-interest that gives them running room to market their product.”

Philip Morris, BAT, and Japan Tobacco today either own or lease cigarette manufacturing plants in more than 50 countries. The total world cigarette production was 5.6 trillion cigarettes in 2004, or 900 cigarettes for every man, woman, and child on earth.

“Cigarette-marketing techniques used in this country 25 years ago have been exported to developing countries,” says Damon Moglen, vice president for international programs at the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. The marketing transforms how cigarettes are perceived in those countries and creates new demand, especially among women and young people.

“You can find candy-flavored cigarettes sold in boxes to appear like candy to attract children,” Moglen says. “A Dutch company produces a chocolate-flavored cigarette called Black Devil and pink, vanilla-flavored cigarettes called Pink Elephants.”

With the collapse of communism, many former Soviet-bloc countries were in need of money. Transnational tobacco companies, especially BAT and Philip Morris, competed in the 1990s to acquire state-owned cigarette monopolies, either buying them or entering joint ventures. They brought in Western production methods and increased production of brand names like Camel, Winston, and Marlboro that had previously been available only on the black market. Big tobacco no longer needed to export cigarettes to these countries because they were producing them.

Because Eastern European smokers are accustomed to stronger-tasting cigarettes, tobacco companies increased the tar yields of some brands sold there. Under pressure from the companies, many former socialist countries weakened or repealed laws restricting cigarette advertising.

Much of the advertising was directed at women, who traditionally had low rates of smoking in Russia, Eastern and Central Europe, and many less developed countries. Ads portrayed smoking as a sign of independence and modernism, and smoking among women went up. One study found that the smoking rate among women in Albania, one of Europe’s poorest countries, doubled between 1994 and 2001.

“All the transnational cigarette companies in Russia are now promoting their brands to women,” Moglen says. “When you walk down the street in Moscow, virtually every well-dressed woman you see is smoking these long, thin, so-called ladies’ cigarettes that remind you of Virginia Slims. And what I find to be absolutely astonishing is that the smoking rate among women physicians in Russia is higher than among women in the general population.”

Cigarettes, which are expensive in Russia, are also reaching children. Moglen says survey data suggest that among urban schoolchildren, 51 percent of boys and 40 percent of girls in grades 9 through 11 smoke. “The age when kids begin smoking in Russia is thought to be about 10 for boys and 13 to 14 for girls,” he says.

Trends appear similar in other former communist-bloc countries where aggressive ad campaigns—in Romania, a Camel ad appeared on the amber light in a traffic signal—have helped drive up smoking rates to among the highest in the world. Surveys indicate that 50 percent or more of Eastern European men smoke. A 2005 report by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine at the University of London found the risk of tobacco-related premature death for men in the former socialist countries to be twice as high as in Western democracies.

“As much as the tobacco companies would like the world to believe they have fundamentally changed their behavior, their cigarette exports and marketing practices in developing countries are proof positive that they haven’t changed at all,” says Mitchell Zeller, an associate commissioner of the FDA during the Clinton administration and now an attorney in Bethesda.

China remains the market that Western cigarette makers dream about. With an estimated 350 million smokers, China grows more tobacco and smokes more cigarettes than any other country. About 65 percent of Chinese men smoke, and about one-third of all the cigarettes produced in the world are smoked in China. Virtually all of China’s cigarettes are produced by the state-owned China National Tobacco Corporation.

Big transnational tobacco companies have a toehold and want to gain full access to the Chinese market, where less than 5 percent of women smoke. Philip Morris has signed a licensing agreement to sell Marlboros in China and agreed to help China internationalize its cigarette sales.

According to Moglen, China is wrestling with its cigarette problem. In 2006, taxes and profits from the state-owned tobacco industry accounted for 7.7 percent of the central government’s revenue. But an estimated 1 million people a year die in China from tobacco-related illnesses, and Chinese health officials are aware of the strain smoking places on the country’s overburdened healthcare system.

China is a signatory to the FCTC and, according to Moglen, is working to strengthen its ban on tobacco ads, developing policies for smoke-free public spaces, enlarging the warning labels on cigarette packages, and stepping up public education about the harm of tobacco use.

“If any of the multinational tobacco companies get a major foothold in China and are able to employ Western-type promotion techniques, it will have a devastating effect on the health of the Chinese population,” Moglen says.

One way big tobacco companies have found to “capture the culture” of countries is by offering financial incentives to farmers to grow tobacco. Today more than 120 countries grow tobacco, according to the Tobacco Atlas, and an estimated 33 million people work to cultivate it. China grows far more tobacco than any other country. It and the three other major growers—Brazil, India, and the United States—produce about two-thirds of the world’s tobacco.

In the US, tobacco acreage has increased by 20 percent in the last two years despite the ending of tobacco subsidies. The United States exported 330 million pounds of tobacco in 2006.

Two African countries, Zimbabwe and Malawi, are major tobacco producers, and many Asian countries, including Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam grow tobacco, making it the most widely grown nonfood commercial plant in the world.

A Yale University study estimates that 10 million to 20 million of the world’s starving and undernourished people could be fed if farmers grew food on their land instead of tobacco. This is unlikely to happen because many farmers get foreign-exchange guarantees for their crops from big tobacco companies. According to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, nearly 600 million trees a year are cut down to provide the fuel needed to dry tobacco.

Some countries have resisted tobacco exports. Taiwanese groups held public protests against American cigarettes and advertising, calling the trade tactics that forced cigarettes into their country “an abuse of dignity.”

After a long struggle, the Philippines passed a number of antismoking laws in 1995, though they were criticized by Philippine health officials as “too little too late” because 73 percent of adults and 56 percent of children had become smokers.

Thailand has successfully resisted a tobacco culture even though at one time it was awash in cigarette advertising after failing to keep out cigarette exports. Dr. Koop recalls visiting Bangkok years ago: “You might have thought the name of the city was Marlboro. It was on taxicabs, billboards, even on the spine of three-ring binders the kids brought to school.”

Intensive efforts by Thai officials and anti smoking organizations succeeded in banning tobacco ads on television, requiring very strong warning labels, and instituting other antismoking measures that resulted in a drop in tobacco use.

More countries are taking stands against tobacco. Uganda recently enacted a clean-indoor-air law, and this year a number of states in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, sued American tobacco companies and British American Tobacco for billions of dollars on the grounds that they are responsible for smoking-related illnesses and healthcare costs.

Despite some positive signs, there is not a lot of optimism that WHO’s forecast of 1 billion smoking-related deaths by the end of this century won’t be met.

Dr. Koop and other public-health leaders hope that the FCTC treaty can help reduce the death toll. Whether the treaty ultimately will be seen as a well-meaning but ineffective gesture or is made strong enough—with United States backing—to avert what Allan Brandt predicts will be “one of the worst epidemics in human history” is yet to be decided.