Brittany Jones and Zach Kimble barely knew each other before that night. She was a sophomore honors student who’d just bought a dress for homecoming and couldn’t wait to start driving. He was a senior with his heart set on a wrestling title, making plans to go to college. Had they passed in the hallway of Damascus High School the next morning, they might have said hello.

Brittany wasn’t supposed to be riding with Zach that night in October of last year—her mother and stepfather didn’t let her drive with other teenagers—but two of her friends were getting a ride with him and it was only a few miles to the Burger King in Damascus, where the teens went after Young Life meetings.

“Come with us,” a friend said. So she did.

The five kids in the car had spent an hour at a meeting of Young Life, a Christian group for teens, where they sang, played games, talked about Jesus, and had a closing prayer.

“God, keep us safe as we go to Burger King. Help us continue to have fun hanging out,” a group leader said. “Amen.”

When Young Life ended, Brittany got into the back seat of Zach’s parents’ Volvo. Her friend Kirstin Newport, a cheerleader, went to get in next; Ryan Didone, the 15-year-old son of a Montgomery County police commander, switched places with Kirstin at the last minute so he could sit between the two girls.

Ryan was a class clown who had come home from Young Life camp that summer with a Mohawk. He raced dirt bikes on weekends and wore a cross around his neck.

The car was packed, the radio was on, and everyone was singing. It was a cool, dry night. Some of the seat belts weren’t touched. It was dark, and the two-lane winding road in upper Montgomery County didn’t have streetlights. Around 9:05, Zach came down a hill, picked up speed, saw headlights, and panicked.

A year after the accident, Brittany has no memory of a shock-trauma doctor shaving off the long brown hair she used to straighten every morning. She can’t recall much about the 16th-birthday party she had two weeks before the crash.

Her friend Kirstin, the cheerleader who was with her in the back seat, told her they had looked at each other before the impact and yelled, “Slow down!” Kirstin says that moment still plays in her head. Brittany doesn’t remember it.

Zach, the driver, remembers the look on the face of his friend Chris Nicholson, who was sitting next to him in the front and later was trapped in the burning car. Zach doesn’t sleep well because he’s scared of what he’ll see when he closes his eyes. He’s supposed to be off at college now, but he’s living at home and making a little money laying brick.

Ryan’s father has spent 15 years of his police career working on traffic safety, most recently focusing on teen drivers. He started speaking at high-school assemblies again a few months after the accident, this time showing students the mangled Volvo station wagon in which his son died.

The five teens—Zach, Brittany, Ryan, Chris, and Kirstin—weren’t legally allowed to be riding in the same car that night. Zach had received his provisional driver’s license less than three weeks earlier.

Under Maryland’s graduated-licensing system, designed to give young drivers more experience, teenagers can’t transport passengers under age 18—except family members—for the first 151 days of the provisional period without a supervising adult in the car.

Zach loaded up his parents’ Volvo anyway and went too fast—changing the lives of five young people and their families forever.

Almost everything about Brittany Jones’s bedroom says teenager, starting with the walls. Her grandfather painted them for her while she was in the hospital.

“I’m obsessed with turquoise now,” she says one morning in September of this year. “I don’t know why.”

Her dresser drawers look like school lockers. A poster from Twilight, a movie about a young girl who falls in love with a vampire, hangs above her bed. Glamour and Seventeen magazines fill a rack on the wall.

What seems out of place is a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle on Brittany’s desk. Her mother and stepfather like for her to work on it to stimulate her brain.

“I do, like, a half hour every day,” says Brittany, who’d hoped to be an emergency-room doctor one day. “I sit and stare at it because I can’t get any of the pieces.”

It was her stepfather—a Pentagon police sergeant—who answered the phone that night in October last year after the car Brittany was riding in hit a tree. Kids from Young Life had been caravanning to Burger King, and the teens in the car behind Zach’s stopped when they came upon a tree limb in the road.

A Young Life leader named Bobby Patton pulled his van over and saw Zach walking toward the road and flames in the woods. Patton ran to the burning blue Volvo and found Chris trapped in the front seat. The back door was open, and Kirstin was sitting up, dazed but conscious.

“Can you walk?” Patton asked her. He helped Kirstin out, left her with another adult, and went back for Ryan, who was slumped over in the middle seat.

“Ryan! Ryan!” he said. “Come on! Come on!” He picked him up and laid him on the ground, then tried to put out the fire in the engine by tossing dirt on it. He went back and forth between Ryan and Chris until help arrived. Another group leader pulled Brittany from the back seat and carried her up to the road. She had a deep gash in her forehead.

Brittany’s parents, Joe and Tammy, had been getting ready to put their nine-month-old son to sleep when the call came. Brittany adored Logan, her baby brother, and couldn’t wait to take him trick-or-treating. She’d already decided she wanted four kids of her own—two girls and two boys.

The Volvo hit a tree when it went off the road. The car shows even more damage in this photo—it was taken after rescuers extracted Chris Nicholson from the front seat. His legs were pinned under the dashboard of the burning car. Photograph of car courtesy of Montgomery County Police Department.

When Joe answered, one of Brittany’s friends was screaming into the phone.

“Slow down,” Joe said.

Brittany had been in an accident, the girl said, and was lying in the street. Joe and Tammy thought Brittany had been getting a ride to Burger King with a Young Life leader. They were strict with her: When she went to her boyfriend’s house, she had to text her mom a photo to prove there was an adult home. She knew the rules.

When Joe got to the site on Hawkins Creamery Road, he found Brittany in an ambulance, her head bleeding and her right arm broken. She was yelling that she couldn’t feel her legs.

Zach, the 17-year-old driver, was sitting behind her holding his wrist.

“It’s all my fault,” Joe remembers him saying. “It’s all my fault.”

Tom Didone, Ryan’s father, had been to hundreds of accident scenes. For a couple of years, it was his job to reconstruct fatal crashes in Montgomery County. That night, he saw the crushed Volvo and assured himself, “Ryan always wears his seat belt.”

Tom and his ex-wife, Marlene—a former Rockville police officer who teaches driver’s education at I Drive Smart—always told Ryan and his older sister, Kara, “The car doesn’t start until your seat belt’s on.” As Ryan got older, they’d never had to remind him.

Marlene had gotten a call from a friend around 9:15 that night, warning her to avoid Hawkins Creamery Road when she went to pick up Ryan because there’d been an accident. Marlene’s daughter, Kara, dialed Ryan’s number to make sure he was okay; when he didn’t answer, she dialed again. She called the Germantown police, but they could tell her only that it was a blue vehicle with five passengers. Then she called her dad.

“We think Ryan was in the accident—he’s not answering his phone,” she said. “What can you do?”

At the scene, Marlene ran past the police tape to look in the ambulances. Her kids had lived with her since she and Tom divorced five years earlier. She would drive Ryan to the track in Frederick after school so he could ride his dirt bike, and she spent weekends watching his races. He gave her a hug every time he left the house.

Paramedics were working on Ryan in the ambulance when Marlene found him. Kara, a student at Montgomery College, stood next to the ambulance and watched as firefighters extracted Chris from the front seat of the Volvo.

Kara knew Chris—a senior shooting guard vying for a Division III basketball scholarship—through Ryan. He’d been trapped more than 20 minutes in the front seat of the Volvo, at times with flames inches from his face. The fire was out, but he was screaming, “My legs are burning!”

“You’re not on fire anymore,” a captain was saying. “You’re not going to die. We’re going to get you out of here.”

Kara took pictures of the Volvo on her cell phone to show Ryan later what he’d been through. She kissed her brother on the head before he left in a Medevac helicopter.

An EMT told Joe they’d be taking Brittany to Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, but when he and Tammy got to the ER, Brittany wasn’t there. Two ambulances pulled up, and she wasn’t in either one; Chris and Brittany’s friend Kirstin were.

“Somebody needs to find out where she is,” Joe told a woman at the front desk. She gave him the number of the shock-trauma center at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore.

“I’m looking for my daughter,” Joe said when he called. Two accident victims had just arrived, he was told.

“What’s she wearing?” the nurse asked.

“Jogging pants and a tie-dyed T-shirt.”

“She’s here.”

It was about 11 pm when Joe and Tammy pulled out of the parking lot at Suburban. Tammy—who had moved to Washington from Florida with Joe and Brittany in 2005—didn’t know the area well and had never heard of the Baltimore shock-trauma center. On the drive there, she pictured Brittany with stitches and a cast. She expected to find her daughter looking for her, wondering what had taken her so long. Instead she found Brittany unconscious, covered in blood, tubes everywhere.

“You need to sign this,” a nurse said, waving a consent form. “We have to operate now.”

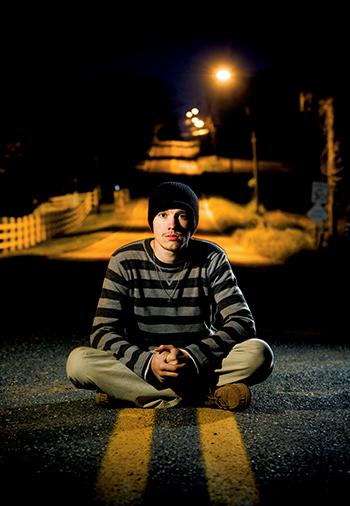

A year after the accident, Zach Kimble arrives for an interview in khakis and an American Eagle T-shirt. He’s wearing a Texas Longhorns hat backward. When he was young, he dreamed about going to college there. His wrestling coaches called him Cowboy.

Zach rarely talks about the accident. He’d hoped to get a college degree in psychology, become a Marine, and then get a job with the Drug Enforcement Administration or the CIA. Now he can’t fall asleep without TV or music because the silence is hard to bear. The accident is always there.

“I remember bits and pieces of what happened,” he says. “It’s almost like a strobe-light effect.”

There are moments Zach sees clearly, sometimes in his dreams, and parts of that night he can’t see at all.

Brittany Jones—shown with her family—was in the back seat of the Volvo that crashed. Her injuries required more than 11 hours of surgery; she spent seven weeks in rehab and is still in physical therapy. Brittany, who had been planning to take AP classes this year, is in regular-level classes as she recovers from the damage to her brain. Of Zach, the driver, she says: “He should have to live a day in my life.” Photograph of Jones by Matthew Worden.

“I remember coming down, going around the curve, and I saw bright headlights. So I hit the brakes a little bit, and I pulled the steering wheel to the right—just a little bit, just to compensate and make sure the person had enough room—and my right front tire caught gravel. And no matter what I did, I couldn’t get control of it.”

He remembers waking up in the car, running up to the road from the woods, yelling for help. He remembers trying to get his friend Chris out of the front seat, away from the flames, and not being able to get the door open. He and Chris were close—they were always shooting hoops and hanging out. “I just felt so helpless,” Zach says.

The small fire in the Volvo’s engine was almost like a trick candle. People who stopped to help were pouring bottles of water and Gatorade on it. An off-duty detective used his fire extinguisher, but the flames kept coming back.

“The only thing that I could do was reach in and get his seat belt off, and then my friend came and pulled me back up to the road,” Zach says. “And then I black out again.”

Neurosurgeons had to remove a portion of the right side of Brittany’s skull hours after the accident. The trauma to her head had caused blood vessels to tear and leak and to form a thick layer of blood clot on her brain. She arrived at the shock-trauma center alert and talking, then lost consciousness. Removing part of the skull relieved the swelling in her brain and allowed surgeons to remove the blood clot.

Doctors performed 11 more hours of surgery the next day, repairing a crushed sinus cavity in her forehead and treating a collapsed lung and broken arm.

The day after the surgery, Tammy saw two teens standing in the hallway. “We’re looking for Brittany Jones,” one said.

Brittany’s head was shaved and bandaged. A neck brace covered most of her face. Her brown eyes were swollen shut.

“This is her,” Tammy said.

Joe asked Brittany’s friends not to talk to her about the accident or about Ryan. She’d suffered a brain injury. She was starting to wave and respond to simple commands, but she didn’t know what happened in the crash. “Hi, Brittany, you’re in Baltimore,” nurses would say. “You were in a car accident.”

Doctors were able to remove Brittany’s breathing tube, but she developed a blood clot in her arm and an infection. She had limited movement on her right side. Each day Tammy sat by her daughter’s hospital bed, trying to get her to say something.

Marlene Didone called her pastor on the way to Baltimore’s shock-trauma center, where Ryan had been sent. The police officer who was driving her and Kara got lost, which Kara later saw as a blessing—less time in the waiting room, wondering.

Marlene had known Ryan was getting a ride to Young Life with Zach that night—he’d texted her to ask permission. He checked with his mom before he went anywhere. His sister didn’t know Zach, but she’d heard Ryan talk about him. She and her mom knew that Zach was two years older, and they assumed he’d been driving long enough to take teen passengers.

“He had driven him a handful of times in the summer,” says Kara, “with us being under the impression that he did in fact have his full license.”

Before Tom got into his car to drive to Baltimore, police officers told him how serious Ryan’s condition was. By the time he arrived, his son had lost a lot of blood. As a police officer, Tom had always watched bad things happen to other people. He’d spent years locking up drunk drivers and been in dozens of ERs. Now it was his child.

Tom hadn’t seen much of Ryan in the weeks before the accident. They hadn’t been getting along—Ryan and Kara had sided with their mom during the divorce. Ryan was training to make it to the amateur national motocross championship. Tom told his son the sport was too dangerous.

“Why can’t you support me?” Ryan asked. He told his dad he didn’t want to be a cop, even though he told Kara he really did.

Tom and Ryan got along best fishing and playing golf. “I could see what a good kid he was,” Tom says. “And how lucky I was.” He’d called Ryan a few days before the crash and said he was proud of him.

Around midnight, three hours after the closing prayer at Young Life, a shock-trauma doctor came to talk with Ryan’s family. Tom knew what the doctor was going to say—he recognized the expression. As a cop, he’d had to knock on doors and tell parents they’d lost a child. How am I going to say this? he’d think. What words am I going to use?

Zach and Ryan had become friends during a Young Life trip to Colorado the summer before the accident. The ride took 30 hours each way. “It was the longest trip ever,” Zach says.

He and Ryan stayed in the same cabin and spent a week enjoying the outdoors—volleyball tournaments, an obstacle course. They swapped stories about girls and sports—Ryan’s life revolved around motocross; Zach traveled a lot for wrestling tournaments. They took walks at 6 am and talked about God.

“There’s pictures everywhere,” Zach says. “Me and him. Me and him. Out in Colorado.”

One night at camp, counselors turned off the lights and everyone sat outside in silence for 15 minutes. Afterward, the teens got together and listened to “Amazing Grace,” and Ryan’s friend Kirstin started crying. Ryan gave her a hug.

“If you really want to talk to someone, you should talk to Zach,” he told her. “He’s the most Christian person I know.”

When Zach and Ryan got home from camp, they were inseparable. They ate lunch together in the cafeteria. They hung out and rode four-wheelers. Ryan told his auto-mechanics teacher, a church deacon, “I gave my heart to the Lord this summer.”

Shortly after the accident, Zach’s parents told him the news while he was lying in the ER at Montgomery General Hospital. His friend Ryan was dead.

In Damascus, people go to high-school football games even if they don’t have kids. A church sign reads: tell your wife and kids you love them.

The line at Ryan’s viewing wrapped around the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer. Ryan’s grandmother put her arms around every teen who walked by Ryan’s casket. “Please don’t let this happen to you,” she said.

When Ryan’s funeral procession passed through town the next morning, four days after the crash, strangers stood outside to watch.

“We should never forget the life lessons we’ve learned out of this experience,” Ryan’s father said in his eulogy. It was the morning of the homecoming football game. “Starting tonight, when we kick Seneca Valley’s ass, we will begin going down the path of healing.”

He had spoken at a candlelight vigil less than 24 hours after Ryan’s death; some were surprised he could stay so composed. He saw this as a chance to get through to kids. Now he wasn’t just a cop; he was a cop who’d lost a son. He wanted to speak out while Ryan’s peers were listening.

Chris Nicholson—who’d spent four days at Suburban Hospital after he was rescued from the burning car—convinced doctors to let him go to the funeral. He arrived in a wheelchair. He had leg injuries, fractures in his face and hand, and crushed sinus cavities.

A police officer told Chris that if he hadn’t been wearing his seat belt, he would have died one of two ways: His head would have gone through the windshield or he would have broken his neck.

According to police, Chris was the only one in the car wearing a seat belt. Zach says he had his on; the crash investigator says he didn’t. Brittany, Ryan, and Kirstin—all in the back seat—weren’t wearing theirs. Ryan died of multiple head injuries. The force of Brittany’s body slamming into the front seat was part of the reason Chris was pinned under the dashboard.

Ryan’s friends showed up at the homecoming game with “101,” his motocross number, painted on their chests. The players ran through a banner that read: we have an angel on our side.

Zach wanted to go to Ryan’s funeral, but his parents, Scott and Sheri, wouldn’t let him. They’d called their pastor for advice.

“We were afraid that if he went, it would hurt people,” says Sheri. “We didn’t want any of the focus put on him.”

The next day, the Kimbles were driving home to Mount Airy when they passed by Ryan’s family’s church.

“We have to stop,” Zach’s father said.

Sheri pulled into the parking lot, and Scott went inside.

The pastor was on the phone. “Can I help you?” he asked when he hung up.

“I’m Zachary Kimble’s father.”

The pastor looked stunned. He told Scott he’d just been on the phone with Ryan’s mother talking about Zach.

Zach and his parents had been wanting to visit the Didones but couldn’t reach them. The pastor arranged a meeting.

When they spoke, neither family had an attorney. Scott and Sheri apologized and asked what they could do. When Zach broke down, Ryan’s parents embraced him.

As time went on, their compassion faded. Zach told a police officer he thought he’d been going about 50 miles per hour when he lost control of the car; the speed limit is 35.

The investigation showed that the Volvo’s registration was expired and the year decals were hidden by a cover around the license plate. Sheri had been stopped that summer for driving with expired tags. Zach’s parents had excluded him from their car’s insurance policy. According to the police report, someone called GEICO at 10:08 the night of the crash—about an hour after the accident—requesting that Zach be added back to the policy.

Zach’s driving history was complicated. He’d had his first learner’s permit nearly two years before the crash, but it was suspended when he didn’t pay the fee. The suspension was lifted in July 2008, but the permit had expired by then. Zach completed his classroom courses and “behind the wheel” time that summer—he didn’t need a permit to drive a vehicle in an accredited driving school—and was issued a second learner’s on September 13, 2008.

Sheri signed off on Zach’s driving log—Maryland teens have to drive 60 hours with an adult—and he got his provisional driver’s license on October 2, 18 days before the crash. Police say Zach did his 60 hours of practice driving without a valid learner’s permit; his parents say they thought the permit was valid when they paid the fee and that the Motor Vehicle Administration never told them otherwise.

“This kid had no business being on the road,” Ryan’s father says.

After the accident, Zach’s parents made him stay upstairs, closer to their room. His bedroom was in the basement, and he wasn’t eating or sleeping. He didn’t want to leave the house. When he did go out, he says, “I tried to put on a mask.”

The night of the homecoming dance—five days after the accident—Zach, Kirstin, and their dates went to Chris’s house for a quiet dinner. Ryan had just been buried; Brittany was still in shock-trauma.

Zach had apologized to Chris when he visited him in the hospital—there was a good chance his friend’s dreams of playing college basketball were over. “It’s okay,” Chris had said.

Chris didn’t remember anything that happened after the closing prayer the night of the accident. He didn’t know that for a few minutes, while he was still in the Volvo, police couldn’t tell his parents whether he was breathing.

When Chris’s mother heard Zach had been driving, she told police: “He couldn’t have been driving—he wasn’t allowed to have anybody in the car yet.”

When Zach’s parents dropped him off at Chris’s for dinner on homecoming night, Chris’s mother, Jeanette, thought: Here’s a family whose kid made a mistake.

One of the parents had brought over a nice meal, and Jeanette served Chris and his friends dinner. She thought it was strange that Zach didn’t seem more distraught.

A few weeks later, she says, Chris went on Facebook and saw photos of Zach at a party: “I think that’s when Chris got angry. Chris would say, ‘Why isn’t Zach cutting Brittany’s family’s yard? They’re at the hospital every day—why isn’t he helping them?’ ”

Attorney Tom Heeney met Zach Kimble and his parents in his Rockville office eight days after the crash. He says Zach was somber and tearful and took full responsibility. This could be anyone’s son, Heeney thought.

Zach told Heeney he was in the ROTC program at school. He told him about the auto-tech club—he loves working on cars—and his A average at school. He said he wasn’t sure where he wanted to go to college. SATs were coming up.

The Kimbles, Heeney learned, were struggling financially and were renting a house in Mount Airy. Sheri was homeschooling her younger son—Zach has a 9-yea

r-old brother and 17-year-old sister—and Scott was doing commercial and residential appraisal work. He’d recently taken a pay cut, which meant Sheri would be going back to work soon.

They told Heeney they hadn’t realized Zach was still excluded from their car insurance—they thought they’d corrected that, and Scott called the night of the accident to be sure. Sheri says Scott made the call to GEICO that night just after 9—the police report says 10:08—before he’d heard about the crash, because their premium was due and he was trying to clear up the confusion about Zach’s coverage.

The Kimbles’ health insurance wasn’t going to fully cover grief counseling for Zach, and they couldn’t afford to pay out of pocket. Later they tried three therapists, but Zach didn’t feel any of them understood what he was going through.

While police investigated the crash, Heeney asked Zach not to talk to anyone about it. Zach couldn’t go around expressing remorse even though it would feel good to reach out and would be the right thing to do. It might damage his legal situation.

His parents couldn’t talk, either. “We wanted to talk to the families,” says Sheri. “We wanted to be there.” She was getting e-mails from people she’d never met, accusing her family of hiding behind their faith, asking why they wouldn’t speak out. “They didn’t understand that we couldn’t.”

When Zach and his parents showed up at shock-trauma—where Brittany would spend three weeks—Tammy hadn’t heard any details about the crash. Zach went into Brittany’s room and held her hand for a few minutes. His only injury was a broken wrist.

“I just kept thinking: It was an accident—it was really nobody’s fault,” Tammy says.

She knew Zach was inexperienced, but she didn’t know how fast he’d been going and that he’d driven illegally.

This kid’s going to have to deal with this the rest of his life, Tammy thought. For a while, she felt bad for him.

She went online and saw blog posts about the crash that blamed parents for not paying closer attention to what their kids were doing. She’d always worried about the narrow roads around Damascus. Brittany, who had her learner’s permit, wasn’t allowed to ride with anyone other than a parent.

“You can be the most churchgoing person in the world and you can instill values in your kid, but it all comes down to the decisions they’re going to make when they’re not around you,” says Brittany’s stepfather, who took off three months to help care for her.

Zach and his parents aren’t the only ones Joe blames. “She knew better than to get in the car,” he says of Brittany. “She knew better than to not wear a seat belt.”

There was a bigger crowd than usual at Young Life the week after the crash. Friends of Ryan’s came to see why the meetings had meant so much to him—he’d posted “God is my #1” on Facebook. Zach and Kirstin were in the audience as the group prayed for Brittany’s and Ryan’s families.

Kirstin—who had a broken wrist, pelvis, and tailbone along with fractures in her face—was so traumatized after the accident that she had to sleep with her mother.

Friends told Kirstin they’d heard she’d lost both of her legs; someone sent her a text message saying Brittany had died, a rumor that was going around school. She saw comments online about how the kids in the car must have been drinking.

She kept telling herself Ryan was on vacation and she’d see him when she went back to school.

As the weeks went on, kids in Young Life started asking questions. How could this happen? Why would God let it happen?

“I don’t know how to answer that,” says Brian Jablonski, a Young Life leader who’d given the closing prayer the night of the crash. “Kids said, ‘You prayed for safety.’ ”

Jablonski, who’d pulled Brittany out of the car that night, talked to a pastor at his church. The pastor told him, “Sometimes God’s not good with the ‘why.’ ”

Montgomery County police detective Bruce Werts analyzed fresh marks on the tree Zach hit and the damage to the Volvo. He looked at tire marks in the grass—there were no skid marks on the road—and measured the distance from where the Volvo left the road to where it hit the tree.

He calculated the energy needed to crush the car and how much it took for the car to rotate and drop. Using those numbers and others, he determined that Zach had been going at least 55 miles an hour.

The driver of the oncoming car—a mother taking her teenage daughter home from confirmation class—told police she thought the Volvo had been going at least 70 and she’d expected a head-on collision. Her car never made contact with Zach’s, and she and her daughter were uninjured.

Kirstin told Werts she’d looked at the speedometer before the crash and it was “to the right, past the straight-up position,” which put it in the area of 73 to 85 miles per hour.

Werts didn’t have evidence to prove any of that.

Tom Didone tried to stay out of the investigation. He didn’t want anyone to claim that he’d influenced the case.

“I kind of tried to play the role of a parent,” he says.

It would be months before investigators decided whether or not to charge Zach.

Tom started telling Ryan’s story at high-school assemblies and parent meetings. At some of them, he’d expect 60 parents and about six would show up.

“I’ve been told countless times about parents that really don’t even spend the time in the car with their kids—they just fudge it,” he says. “Some parents don’t want to be taxi drivers anymore. I would be a taxi driver for my son for the rest of his life if he would come back.”

Doctors put mitts on Brittany’s hands because she kept trying to pull her tubes out and scratch the staples in her head. When Tammy took one of the mitts off so she could hold her daughter’s hand, Brittany went right for the tubes. Tammy pushed her arm away.

“Stop!” Brittany said.

Joe looked up from his laptop: “What did you just say?” Two weeks had passed; she hadn’t spoken since the accident.

“I have to itch,” she said.

She was transferred to the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore for rehabilitation. She was still eating through a tube, and her neck was fractured, so she had to wear a brace.

Brittany’s grandparents were with her when she first started asking questions.

“I’m really confused,” she said. Her grandmother ran to get Tammy.

Tammy and Joe told Brittany about the car and Ryan. She didn’t say much.

“I don’t think it processed,” Brittany says now. Doctors advised them not to bring it up again until she did.

Months later, someone asked Brittany if she’d been at the wheel when the car crashed. She didn’t know.

“Mom, was I driving?” she asked.

Brittany spent seven weeks in intensive occupational and physical therapy at Kennedy Krieger. She played Nintendo Wii to work on mobility and learned to walk with a cane. At one point, a social worker asked Tammy, “Does this feel like the new norm?”

The question angered her. Brittany had played soccer and volleyball. The day after the accident, she was supposed to shop for shoes to wear to homecoming. Now she was learning how to dress herself. This will never be normal, Tammy thought.

Zach went back to Damascus High two weeks after the crash. Chris and Kirstin had to spend a few months at home recovering; Brittany would be out for most of the year.

Zach spent the first few days in the counselor’s office. Some of his friends—including Chri

s—stopped speaking to him. Zach couldn’t go to the cafeteria because he and Ryan had always eaten lunch together.

He heard that people were talking about him. “I was called a murderer,” he says. “That’s one that has stuck with me.”

When his grades started dropping, Zach switched to a part-time schedule. He put off plans for college.

Ben Patton—whose brother Bobby is a Young Life leader who helped pull the teens from the car—told Zach he wouldn’t bring honor to anybody by letting the tragedy destroy him. He needed to go on.

“That was one of the struggles,” says Patton, a father of seven. “How does a 17-year-old boy do that without having the appearance that he doesn’t care?”

People in town recognized Zach when he was out. At school, he felt peers were whispering. “Oh, that’s Zach Kimble,” he imagined them saying. “He’s the one who crashed that car on Hawkins Creamery Road.”

Brittany came home from Kennedy Krieger just before Christmas weighing 97 pounds. Her hair hadn’t grown out, and her head looked flat on one side.

She was scheduled to have the bone in the right side of her skull repaired in December, but an infection postponed the surgery for three months. At home she wore a foam helmet to protect her head. Sometimes her baby brother didn’t recognize her.

Brittany couldn’t be left alone. She wasn’t able to stand for more than a few seconds because she couldn’t keep her balance. She’d laugh for no reason. “When you would talk to Brittany, her mentality was that of about a ten-year-old,” says Tammy.

She’d eat a big dinner, lie down to go to sleep, and tell Tammy she was starving—she didn’t know when she was full. She hardly spoke.

Before the crash, Brittany had been a teen who only wanted to wear Hollister and Abercrombie. She and Tammy would sit in the car and sing along to the radio or just talk. Not anymore.

“For the first three months, she would just sit in the back seat and stare out the window,” Tammy says.

She and Joe bought bed rails and a chair for the shower so Tammy could bathe Brittany. When one of them went to help her get up from the couch, Logan would run and open the bathroom door and come back to help push the wheelchair.

Tammy had planned to work part-time after Logan was born, but now she was caring for a toddler and a teen.

When Tammy was driving Brittany to physical therapy one day, she started thinking about Zach. He should be here, Tammy thought. It’s not fair that he’s off at school or a football game and I’m helping Brittany deal with the life she’s been given because of his mistake.

Ryan’s family wanted Zach charged with vehicular manslaughter. They wanted to see charges brought against his parents for allowing him to drive without insurance and violating the terms of his provisional license.

“His parents handed him the loaded gun, and he pulled the trigger,” Ryan’s sister, Kara, says.

Zach’s mother didn’t realize that her son wasn’t allowed to drive other teens. They’d moved from New York two years earlier. “We did not know the laws, and we should’ve known them,” she says.

Brittany’s parents wanted Zach’s family punished. Her stepfather had a friend who’d been killed by a drunk driver and, at the request of the victim’s parents, the judge had made the man send a $1 check to the mother every week. On it he had to write: “This is for killing your son.”

Assistant state’s attorney Paul Zmuda struggled with the decision. To charge Zach with vehicular manslaughter—which for juveniles carries a range of penalties including probation, placement in substance-abuse treatment, or up to 12 months in a juvenile detention center—Zmuda would have to prove that he’d been driving in a grossly negligent manner.

In Maryland, gross negligence is defined as “a wanton and willful disregard for human life,” and in rare cases excessive speed alone can qualify. But there’s a high standard for gross negligence—drivers charged with manslaughter have often been drinking or have broken multiple traffic laws, such as running a red light and hitting a pedestrian while speeding through a school zone.

According to Werts’s police report, the Volvo was going at least 55 miles an hour.

“At what point does speed become ‘excessive’?” says Zmuda. “Case law doesn’t exactly say that if you were going 20 miles per hour over the speed limit, that is excessive. You need to look at the environment they’re in.”

A driver going 30 miles an hour over the speed limit on the Beltway might not face the same charges as someone driving that fast on a city street or in a school zone. Zmuda had to consider other factors, such as the curve in the road.

Zmuda and state’s attorney John McCarthy met with Werts and other members of the collision-reconstruction team five months after the crash. Werts laid out his case. They talked about the driver of the oncoming car, who’d said Zach was going faster than 55.

“It’s tough to determine the speed of another car if you’re going the opposite way, so we need to rely on the expertise of the collision reconstructionist,” Zmuda says. “If there were additional factors—if they’d been drinking, if they’d been drag racing—it would’ve tipped the scales towards prosecution.”

Zmuda didn’t think he had enough evidence to charge Zach with vehicular manslaughter. He says the case might have met the standard for a lesser charge of negligent homicide—death caused by an act of negligence—but Maryland doesn’t have that statute. The District has a negligent-homicide charge; Virginia does not.

Maryland has two levels of charges for sober drivers who cause a death: traffic citations and vehicular manslaughter.

“There is far too big a gap,” Zmuda says. The Maryland State’s Attorneys’ Association has been lobbying for more than a decade to make negligent homicide a charge.

“I couldn’t imagine a situation where my wife, son, or daughter got killed and the person’s getting traffic tickets,” Zmuda says. “But many times that’s the situation we are in, given the laws that we have.”

Zach had to pay $710 in fines for his tickets. He never appeared in court, and his driver’s license wasn’t revoked. Because Zach was never charged with a crime, police say, it would have been up to the MVA to take his license away.

“This was not a depraved-heart act. This was not a reckless-endangering act,” says Zach’s attorney, Tom Heeney. “I give credit to the police and to the prosecutor’s office for not making more of this case than it really was—a tragic death, but not as a result of any criminal activities.”

Ryan’s sister, Kara, says she knows kids with drunk-driving convictions who didn’t hurt anybody but are in more trouble than Zach. “It’s just made to look like a joke,” she says. “You go over the speed limit on a windy road and kill someone? Don’t worry about it—just pay $710.”

Damascus High School sponsored a walkathon in May to help Brittany’s family with medical costs. They owed thousands in hospital copays, and their insurance wouldn’t pay for all of Brittany’s therapy. Because Zach was excluded from his parents’ policy at the time of the crash, GEICO wouldn’t cover any of the other passengers’ medical claims. The families had to rely on their uninsured-motorist coverage.

A friend of Tammy’s organized a T-shirt sale; the design was based on Brittany’s favorite Bible verse, Philippians 4:13—I can do everything through him who gives me strength.

Doctors had replaced the bone in Brittany’s skull in March, and she’d started talking m

ore. Soon she took her first steps on her own. A month later, she went back to school for a few classes a day. At night, she hid in her room.

On a Facebook page dedicated to Ryan, she wrote: “last night i read all the newspaper clippings and stuff and cried hysterically. its so hard walking through the halls and not seeing you. your just not there and its so hard to deal with. and esp knowing i was there i coulda done something . . .”

Hundreds turned out for the fundraiser, held at the school track. Brittany walked with Kirstin. “I walked a mile—it was the farthest I’d walked,” Brittany says.

Kara was talking with Brittany and other friends on a platform near the track, wearing Ryan’s jersey, when she saw Zach walking toward her. Kara jumped off the other side of the platform.

“He killed my brother,” says Kara. “It’s in the first six months that he really had to stand up for what he did—and he didn’t.”

A friend told her, “Yes, he killed your brother, but he didn’t intentionally kill your brother.”

Kara doesn’t like to call what happened an accident. She calls it a crash or a collision. “It was preventable,” she says.

Kara met a 23-year-old named Danny McCoy, a Magruder High School graduate who had been driving with a girl he’d just met one night when he hit a telephone pole in Rockville. He was 19 at the time, a Marine who was home for the weekend.

He’d been out drinking in College Park and was on his way home to his parents’ house in Derwood. Danny was okay, but his passenger died. He told the girl’s parents at his sentencing that his focus in life would be to help them with their pain. He wrote them a letter from jail.

“Danny did what I would expect someone to do,” says Kara. “He knew it was his fault.”

When Kara saw Zach’s profile picture on Facebook—a photo of him and Ryan at Young Life camp, with their Mohawks—she asked friends to tell him to take it down. He didn’t.

“He needs to spend some time in jail,” she says. “Maybe not his whole life, but that’s what I would’ve liked.”

Tom Didone spoke at a high-school assembly in Poolesville in May with the Volvo out front. Some schools put totaled cars on display during prom season to deter teens from driving drunk or aggressively.

Kara heard that her dad was taking the car to schools and asked him to stop.

“This is his son that was killed—this isn’t just another accident,” she says. “My brother was killed in that car.”

Tom told Kara that if the car wasn’t there, he couldn’t reach kids the way he did. He said as soon as he mentioned what happened in the Volvo, a hush would come over the auditorium. “I tried to explain to her: ‘The truth is, this time next year no one may want to listen.’ This car is too valuable.”

In April, he stood in front of the car at the Capitol, urging Congress to pass the Safe Teen and Novice Driver Uniform Protection Act, which would establish minimum federal requirements for graduated-licensing laws. Currently, teens in nearly every state go through three levels—a learner’s permit, a provisional license, and a full license—and laws vary.

Maryland teens can get a learner’s permit at 15 years and 9 months; that would change to 16 years. The act would prevent unsupervised teen drivers from having more than one passenger in the car until they had full license privileges at age 18. Teens wouldn’t be allowed to use a cell phone while driving, except for emergencies, until they turn 18.

After the crash, Chris Nicholson’s father took him to Young Life one night and noticed kids speeding out of the driveway. Kara heard a lot of teens say they weren’t going to speed anymore or drive with too many kids in the car.

“None of it’s true,” she says. “I know of a girl that not even three weeks after the accident—she’d only had her license for a month and a half—had six kids packed in the car. I’ve seen the boys coming out of the high school squealing tires.”

Brittany went back to school full-time in September with an individualized education plan designed for special-needs students. “I hate that my brain injury is considered special ed,” she says. She sometimes wishes Zach could see what it’s like for her: “He should have to live a day in my life.”

Her hair is growing out. If it weren’t for the scar on her forehead, you might look at her and not know anything was wrong.

She’d planned to take AP courses as a junior; she’s now in on-level classes and has an aide helping her. She used to get A’s and B’s without studying; math was her best subject. By the third week of classes this year, she was failing Algebra II.

Her mother says, “It’s really hard because people look at you and it’s almost like you can feel them thinking: ‘You need to be happy that she’s alive, that she survived it’—and I am. But I also don’t want to accept that more than likely shes not going to be able to be what she could have been before the accident.”

Brittany often has to reread paragraphs to understand them. She takes the elevator between classes, even though she wants to walk with her friends. If you lose your balance in the stairwell, her mom tells her, people are going to trample you.

Tammy and Joe worry about Brittany’s maturity level. She posts things on Facebook that might normally embarrass her. She wants to babysit her brother, but what if someone texts her and she gets distracted?

Her mind doesn’t work the way it used to—her parents worry that she’ll make a bad decision. They won’t let her go out for pizza with friends unless someone they trust is there—she might not look before she crosses the street. “That’s what most people don’t see,” Tammy says. “They say, ‘Oh, Brittany’s back.’ They don’t see how it has affected her entire life.”

Ryan’s mother, Marlene, started teaching driver’s ed again a few months ago. She tells her students what happened to Ryan. She’s not the only police officer working there who’s lost a teenager in a crash.

She isn’t ready to speak to the media about her son. Her best friend, Robin Mongold, says sometimes Marlene still expects Ryan to walk through the door. The first time Marlene heard a motorcycle, she broke down.

The two women were at Red Robin recently when a group of teenagers walked in. Says Mongold: “I looked at her and I knew exactly what she was thinking, because I was, too: That could’ve been Ryan.”

At the candlelight vigil at school, Mongold saw all the tears and wanted to tell the kids: Remember this. Remember how you feel right now—before you get in the car.

Both of Ryan’s parents were engaged to other people before the crash. Both engagements ended within months of his death. His sister, Kara, couldn’t focus at school, so she left Montgomery College. Now she’s in cosmetology school. She has said she’ll have a baby boy one day and name him Ryan.

Brittany ran into Zach one Sunday last spring. Friends from Young Life had invited her and her parents to their church, and Tammy and Joe forgot that Zach’s family went there. Zach and his parents hugged Brittany—Tammy tried not to look at them—and asked how she was doing.

“It’s good to see you,” they said.

Sheri Kimble had followed Brittany’s progress on her family’s journal on CaringBridge.org, checking the site almost every day.

“I was really inspired to see Brittany walk into our church,” says Scott Kimble. “I can’t tell you how ecstatic I was. Just her presence was absolutely amazing.”

Zach says he thinks about Brittany daily; he occasionally texts or e-mails her. He passes the accident site nearly every week when he goes to Young Life. Friends give him rides; his boss at his masonry job picks him up for work. Zach has a metal plate in his wrist. He says he’s driven a few times since the accident, but he doesn’t like to.

When he dreams about that night, Zach sees the accident happening all over again. This time he’s outside the Volvo. “I see the car coming around the curve. Then I hear Chris screaming,” he says.

Music helps: “There’s a song called ‘Live Your Life’ by T.I., and I heard that shortly after the accident and felt like it was Ryan telling me to keep going.”

Until recently, Zach didn’t talk to his parents about the future. He didn&r

squo;t get his financial aid sorted out in time to register for classes this fall. He’s hoping to go to Montgomery College next semester, then transfer to Towson University. He wants to get out of Damascus.

Asked if his punishment was fair, Zach says that’s not something he thinks about: “I’ve just been thinking more about my friend being gone in an accident where I was driving.”

His mom has thought about it: “That’s a hard question to answer,” she says. “I don’t think they could’ve done anything to him that would’ve been worse than what he’s feeling himself.”

When Brittany sees photos from the weeks after the accident, she feels as if she’s looking at somebody else. “If I think about the past, all it does is make me sad,” she says. ”

Doctors say most of Brittany’s recovery will happen in the first year or two. Because she’s young, she has a better chance of making close to a full recovery, but the fatigue and memory problems may last a little longer. Tammy can’t go back to work because she needs to be home for Brittany, so she and Joe put their townhouse up for sale.

Brittany has been in counseling since she got home from Kennedy Krieger. She’s told her therapist, “I think it should have been me instead of Ryan—I think he was a better person than I am.” Tammy says that’s partly the brain injury talking.

Sometimes Brittany thinks she’s remembering the accident, but she doesn’t know what’s real and what she’s imagining. Tammy and Joe were told she’ll never remember.

“Her mind just shut it out,” Joe says, “and I think that’s helped her heal.”

As the one-year anniversary of the accident approached, Ryan’s sister, Kara, started planning a memorial motocross ride in her brother’s honor. Her best friend, Jimmy Hawkins, a racer she’d met through Ryan, was helping her put it together.

Jimmy had graduated from Damascus in 2007, a year before Kara. There was a photo of him in a newspaper article the day after Ryan’s death, sitting at the crash site, wiping his face with his sweatshirt. He said to Kara at Ryan’s funeral, “You don’t have to worry—I’m going to take care of you.” They’d talked on the phone almost every day since.

On the first Monday in October of this year, Kara talked to Jimmy in the afternoon and he said he’d call her later. She was at home when another friend called.

“Jimmy,” the friend said. He kept repeating the name. “Jimmy. Jimmy. Jimmy.”

“What happened?” Kara asked.

“He’s gone.”

Around 7 that evening, her best friend, Jimmy, had driven his 1989 Chevrolet Cavalier over a hill on a country road in Mount Airy and collided with an oncoming car. Police say he was speeding and driving recklessly. The Cavalier rolled three times, and four people were injured. Jimmy, who wasn’t wearing a seat belt, was ejected from the car. He died at the scene.

This article first appeared in the December 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.