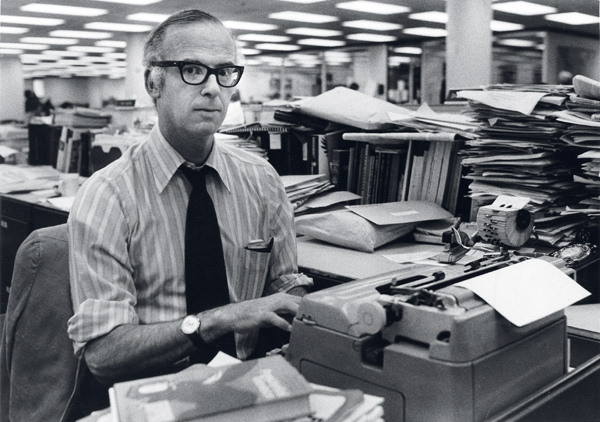

"Decades and decades and decades on the beat," said David Broder's son George, "and not a cynical bone in his body." Photograph courtesy of the Broder Family

When David Broder died in March, the tributes to the journalist—who seemed as much a part of Washington’s political landscape as the Capitol dome—poured in. Those who knew Broder through some of his 81 years reminisced about his commitment to his trade and his uncommon decency.

He had covered 13 presidential campaigns, made 401 appearances on Meet the Press, won a Pulitzer Prize, and written more than 4,000 Washington Post columns that were syndicated in some 300 newspapers.

But his eldest son opened a memorial service at the National Press Club in early April with words his father likely would have chosen:

“David S. Broder was a reporter.”

From college on, he never wanted to do anything else. Broder grew up outside Chicago and earned degrees in political science at the University of Chicago, where he edited the college newspaper and met his wife, Ann. After serving two years in the Army, he began his ascent as a political reporter, getting his start at the Bloomington, Illinois, Pantagraph before moving to Washington in 1955 to work for Congressional Quarterly and after that the Washington Star, the New York Times, and finally, starting in 1966, the Washington Post.

Considered the dean of the Washington press corps, he was immortalized by author Timothy Crouse in The Boys on the Bus as the “high priest of political journalism.”

Broder loved many things: the Chicago Cubs, theater, sitting on the deck of his summer cabin in Michigan with piles of journals and books, the Gridiron dinner, and his family—Ann and their four sons, George, Josh, Matt, and Mike, and his grandchildren. But at the core was his life’s work. “He experienced the world through one lens,” his son Matt said at the memorial service, “the intersection of politics and policy.”

We called on some of David Broder’s family, friends, and colleagues to tell his story.

Next: Family and Friends

FAMILY AND FRIENDS

Mike Broder, youngest of his four sons, management consultant: He was our dad. But so much of who he was was wrapped up in what he did. He was genuinely interested in the subject matter of what he was doing, and he shared that enthusiasm around the house. The phone would ring and you never knew who it would be—a politician, labor leader or organizer, county chairman, chief of staff for so-and-so. That was normal, as was the ingestion of massive amounts of information—the number of papers and magazines and studies and Congressional Records coming into the house on a daily basis was remarkable.

George Broder, eldest son, public-affairs/government-relations consultant: My parents are Midwest and not flashy. We lived in Arlington; we didn’t live in Georgetown. We drove VWs. We bought a little sports car for Dave—we called our father Dave or Big Dave; we didn’t call him Dad—but really just so the brothers could have fun with it.

Stephen Hess, coauthor with Broder of The Republican Establishment: If he had a mentor as a political reporter, it was Alan Otten of the Wall Street Journal. David and Al, to me, were the two great political reporters of their time.

Haynes Johnson, a colleague at the Washington Star and later the Post: We covered stories across the country for more than 50 years. It all started at the Star. Dave came on two years after I joined the Star. From that point on, we became really close colleagues. Dave was the most decent guy in a profession filled with hotshots—people who were on the make, who loved celebrity. He was none of that. Not a fake, not a phony. He was modest. No one worked harder. No one cared about politics more—what it meant to the country.

Victor Gold, longtime journalist and political consultant: In 1961, a friend of mine from Alabama, Charlie Meriwether, had been appointed to the Export-Import Bank by President Kennedy. When Charlie got here, he was greeted by reports in the Post and elsewhere saying he was tied to the Klan. I knew this was not so. So I called an editor I knew at the Star and told him the story. I said, “I’ve talked Charlie into giving an interview with somebody to give his side of it.” And what I said was “Send over the fairest reporter you have.” He sent over David.

Jules Witcover, political reporter and columnist: He was one of the boys, except he was always a little more serious and didn’t engage in the horseplay as much as others, particularly under deadline. He was a straight arrow.

Walter Mears, former political reporter for the Associated Press: We were in Louisville at the end of a long day of travel with Barry Goldwater in 1964. We got in, we relaxed, we might have had something to eat and a couple of drinks. David and I went into the press room to do our stories. I was just kind of daydreaming and thinking about the day and staring at my typewriter.

Broder, who was both fast and good, cranked out his story for the next day’s paper, and then he looked at me and decided that I must have had a couple drinks too many. He took a carbon copy of his story, and without a word he just walked past where I was working and dropped it on my desk and then went back into the cocktail lounge.

I looked and saw what he’d done, and I kinda laughed. I had already figured out what I was going to write, so it caused me to get busy and get the thing cranked out. I wrote my story and made a carbon copy of it, and I put it together with David’s and took both copies back to the cocktail lounge where he was with the other guys. I dropped both of them on the table. I said, “Broder, I can write better drunk than you can sober.” He thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever heard. He said, “The sad thing is you’re probably right.”

Haynes Johnson: Dave had gone to the Times. A great loss to the Star, but they were offering him this golden opportunity to be the lead political reporter. He took it. It was a most unhappy experience. He was very bitter about the bureaucracy at the Times. He was used to an environment where you went out and did your thing without any impediments.

Ben Bradlee, former managing editor and then executive editor of the Washington Post: I had been a reporter for Newsweek in Washington, so I knew most of the reporters very well, and there was one person who was clearly, if not already, the lead man, the comer in the political field. So when I got in a position where I could hire a person, he was the first person I was after. I thought that if people heard that Broder had decided to quit the Times and go to the Post—no one had ever done that—they would sit up and take notice. I worked him over.

George Broder: I remember when he quit the New York Times to go to the Washington Post, even in my 10- or 11-year-old mind, I had some kind of understanding that that can’t be usual.

Haynes Johnson: I had created something for the Star called “The Mood of America” in 1964. I went around the country knocking on doors and writing these series. And when Dave came to the Post, we started together doing the same thing—knocking on doors all over the country. We kept expanding the process, and then we’d get teams of reporters to go with us. We would take a precinct where we knew what the voting patterns were. We had that record. We studied it. We talked to pollsters in advance. Then we would go out and interview from door to door in that precinct, asking everybody the same questions. It wasn’t a survey. We wanted them to talk.

David was just indefatigable at that. He loved it. That’s one of the treasures of my life, those times we spent together on those reports. And if I do say so, modesty aside, they were goddamned accurate.

When he read what we wrote, George McGovern, who thought he had a chance [to be elected President], knew he was going to lose early in the fall of ’72.

Dan Balz, Washington Post political reporter: He always wanted to know what voters thought the biggest problem was and how their own life was going and what they wanted to hear from the candidates. It was always Dave’s view that one of the values of the door-knocking, in addition to the insights you brought back, was a way to channel voters back at the candidates. He was treating people as an integral part of the process rather than a side part of the process.

Next: The Broder Style

THE BRODER STYLE

Dan Balz: On the road, he generally dressed badly: flannel shirts and battered jackets. He never felt the need to be dressed for the next television camera that might show up. He wasn’t a foodie. In New Hampshire, we ate at the Olive Garden as much as we ate at good restaurants.

Maralee Schwartz, former Washington Post political editor: He didn’t want to overspend. You’d pray it wouldn’t be McDonald’s.

Ken Adelman, next-door neighbor for nearly 30 years: Dave, for years and years, took the bus in to work. He would walk over about two blocks, stand out on Glebe Road, and take the Arlington bus. There’d be Dave and a bunch of immigrant workers.

George Broder: He loved sports, and baseball was his favorite. Sports, like politics, has such great clarity. There are winners and losers. Baseball is the most wonderful for statistics. That mind of his was drawn to that in the same way it was drawn to precinct analyses and polling trends.

Haynes Johnson: I met Dave’s parents. His father was a dentist. His mother was quite strong. They were just a lovely couple, and Dave was so proud of his family and where they came from. Once we were driving in New York close to the lower end of Manhattan, and there was the Statue of Liberty. Dave rarely talked about things that were personal. But he got talking about how his family had come through Ellis Island—not his mother or father, maybe their parents. There was a whole series of Broders that came there, and they moved out to the Midwest. I was so touched by this sort of revelation and window into Dave Broder—what drove him, what formed him, this pride in America, this pride in the system, you could make it here.

George Broder: When my parents had dinner parties, they would have us sit in the living room on the floor and listen to the grownups’ discussion during the cocktail hour. It would be someone like Senator Pat Moynihan, maybe another journalist, maybe an ambassador.

Josh Broder, second-eldest son, leadership coach and trainer: When I was about nine, my father took his four sons to the Capitol for a little civics lesson on the legislative process. We’re sitting in the Senate gallery. It’s somewhat crowded with tourists. He gives us a detailed orientation on the process of the Senate. And he concluded saying, “Even if a bill manages to pass the Senate, it’s not yet a law. The next step occurs in the House of Representatives, and we’ll go there next.” My father stood up, and his four sons stood up, and about 15 tourists stood up.

Next: Pounding the Royal

POUNDING THE ROYAL

Stephen Hess: In 1968, I was at Harvard [as a Kennedy Fellow], and I went to New Hampshire to peek in on the primary. He was there. He’d been doing this in 1960, ’64. This was the third time. I said, “David, how can you keep doing this?” He said, “Well, I’ll only do it one more time.” Of course, it became his life calling.

George Broder, recalling the night of March 31, 1968: We were having Sunday dinner, and the TV’s on because Lyndon Johnson is giving an address that evening. My father realizes, “Oh, my gosh, he’s not going to run for reelection,” even before Johnson has said those famous words: “I shall not seek and I will not accept . . . .” He bolts for the door, and within a minute or two the phone rings. It was the paper calling to say, “Get down here.” My mom answers it and says, “He’s already on his way.”

Jules Witcover: He was one of the charter members of the group Jack Germond and I created called the PWDS, Political Writers for a Democratic Society—it was a play on SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. We would meet at Germond’s house and invite politicians. The purpose was to see and hear these people with their hair down and to find out what made them tick.

Jack Germond, political reporter and columnist: We were writing campaign songs all the time. It was a big part of campaigns—on buses, in a bar, sitting around a press room waiting, we’d write songs about candidates and their foibles. We had a song about David to the tune of “Rock of Ages.” It went: “David Broder, write for me. Tell me what is victory. Though the voters make the choice, David’s is the only voice.” He would abide that with a small grin.

Stephen Hess: Ann always kidded that their marriage had been so good because he was away every other year.

Colette Rhoney, former Broder assistant and later Meet the Press producer: What’s ironic is he was one of the first newspaper reporters on TV, but he was as far as you can get from the celebrity journalist of today. He came in so prepared. He had a few typed pages of questions. He had done his reporting and his research, and he was there to play.

Mike Broder: The most obvious ways we interacted or got to see him working was going to the television studios. And then being in the house while he was hammering out columns and stories on his all-steel Royal typewriter. If you had the bedroom underneath his office, your ceiling was shaking when he was pounding on that thing. You could hear it—and you could feel it.

Matt Broder, third-eldest son, vice president for corporate communications, Pitney Bowes: I discovered a postcard some time ago that my father sent to me while he was on a reporting trip in 1964. I had just turned five. On the front was a photo of three basset-hound puppies. “Dear Matthew,” the postcard began, “Do you like these puppies? These puppies are sad. Do you know why they are sad? They are sad because they lost their oil-depletion allowance. Love, Dave.” This postcard explains why my father wrote eight books on politics but not a single one on parenting.

Next: Covering Presidents

COVERING PRESIDENTS

Broder covered every presidential campaign from the Kennedy/Nixon race in 1960 to the Obama/McCain contest of 2008, which he said was his favorite.

Sons Josh, Mike, Matt, and George gathered for a joint 80th-birthday party for their parents in June 2009. Photo courtesy of the Broder family

Lou Cannon, former Washington Post colleague: In ’80, after Reagan lost the Iowa caucuses, we’d both been in New Hampshire. We came back to the newsroom, and Bradlee says, “Hey, I’ve been reading you guys in New Hampshire and I am really confused. I have no idea who’s gonna win.” Broder says to him, “Well, Lou thinks that Reagan’s gonna win and I think Bush is gonna win, and I think Lou might be right.”

A little later, we were in the third row for the debate in Nashua, New Hampshire. And when Reagan did his “I’m paying for this microphone,” Broder just turned to me and said, “Ronald Reagan’s winning this nomination right now.”

Mike Broder on his father’s love of politicians: He admired anyone who was willing to put their name on a ballot and run for office, because that takes tremendous personal courage. But even if he admired someone, that didn’t keep him from calling them out when he thought the person was either doing the wrong thing or had crossed some line.

Lou Cannon: He was very, very close to George H.W. Bush.

George Broder: When Bush [as President Ford’s envoy to China] led the first group of Americans allowed to go into Tibet in decades, he invited my parents. There was a degree of mutual regard and respect.

Dan Balz: He did have a great deal of respect for the decency of H.W. Bush. But once Bush became a candidate for President and then Vice President, he would have put up some kind of wall out of professionalism. There was a particular episode of Meet the Press when Bush was starting to run for President—probably ’87. David was one of the questioners, and he said to Bush, “Many people wonder, given your background, whether you have compassion for ordinary people.” He asked him a series of very specific questions: Do you know how many people don’t have health insurance, for example? He said Barbara Bush never forgave him for that interview.

Broder was one of the few journalists who worked at the same time as both a reporter covering the news and a columnist writing analysis and opinion.

Maralee Schwartz: David, who rarely at that point came out with an opinion in his own voice, came out with a very strong opinion about his disapproval of Bill Clinton and [in columns] supported impeaching him. I had to tell him he had to stop covering the news. I just dreaded it. I walked into his office, and he was so reasonable about it: “Mm-hmm, yes, I understand.” Well, he understood for maybe four weeks.

Dan Balz: At a political staff meeting in late November or early December ’07, he said, “I think Obama’s gonna go all the way.” Others in the room were shocked to hear that because it wasn’t conventional wisdom at the time by any means. It made everybody sit up and rethink what they thought about the race.

Next: The Colleague

THE COLLEAGUE

Lou Cannon: David never cared if his name was on a story at all. Sometimes he’d provide the most information and somebody else’s name would be on the story.

Dan Balz: If you did a story that was halfway good, you got a “That was a terrific story” compliment from David. He encouraged you to follow your own instincts. I always looked to David as the gold standard of how to do the job, and it was mostly from watching him.

Milton Coleman, Washington Post reporter and editor: During the 1984 campaign, David and I were somewhere in New Hampshire before the primary, writing a story. David said, “You know, we need more voices for this piece, and there’s a shopping center not far away and we can probably get some voices there.”

So I started to get up from the typewriter. David said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m going to go to the shopping center.” He said, “No, you stay here and write the story and I will go down to the shopping center and I will feed you quotes.”

For me, that was an extraordinary moment because this was my first campaign and this was David Broder. And here I was writing the story. As a result of that, I developed what I called the “reverse Broder rule,” which was that whenever I met someone on the campaign plane or bus, the more of an asshole they were, the less they knew.

Walter Mears: I once told him he was too nice to be in the business.

Colette Rhoney: On key days as deadline was approaching, Herblock would go back to David’s office and show him cartoons he was considering. Meg Greenfield would stroll in, Mary McGrory would drop in, every once in a while Kay Graham would drop in. There’d be a parade to David’s office.

Dana Milbank, Washington Post columnist, on Broder’s cluttered office: He had a couple of feet carved out so he could get into it and sit in his chair. I imagine you could do an archaeological dig in there and get back to the Johnson administration. Every now and then, there’d be literally an avalanche. He’d be in there and you’d be worried: Was he okay?

Colette Rhoney: I used to clean from the bottom up so he wouldn’t notice. But he would know. I figured if I can’t deal with this fire hazard of an office, I’m gonna take on his briefcase. He must have been carrying it for 30 years. It barely held together. He finally gets a briefcase that’s not a disgrace and he sticks this stuffed tiger tail on it that somebody gave him. The man did what he wanted to do.

Next: Getting It Right

GETTING IT RIGHT

Peter Hart, Democratic pollster: In 1973, I was working for a progressive organization in Wisconsin and I did a poll. I went out and delivered the results, and people gave me great hosannas for my delivery. David Broder was out there as the luncheon speaker. He took my poll from a conservative point of view and ripped it apart. I said to him afterward, “David, that was a great speech.” He said, “Yeah, I ripped you apart.” I said, “Yeah, but I learned a lot.” Essentially, he was saying be smart enough to look at all of this from several different points of view.

Ginny Terzano, Democratic strategist and former Microsoft executive: I asked David if he would sit down with Bill Gates to talk about high-skilled immigration. It was an issue David was interested in, and it’s controversial. David wrote a column on the subject and got a whirlwind of letters and comments. He circled back with me about the facts and figures. He meticulously went through the facts in his column versus the complaints he was getting. He respected the public’s opinion enough that when critics questioned his facts, he took the time to make sure his reporting was accurate.

H.D. Palmer, former staffer for the late senator James McClure of Idaho: Dave struck up a decades-running conversation with Ruthie Johnson, who ran McClure’s district office in Coeur d’Alene and was a delegate to the Republican National Convention. McClure’s staff used to have a running wager about how many minutes it would be into a conversation with Ruthie before she would tell you about the last time she talked to Broder. If you bet long, you lost. She had this high-pitched, creaky voice and would say, “Did I tell you that I talked to Dave Broder the other day?”

On the day Reagan won the presidential nomination in July 1980, Dave wrote a column called “It’s Ruth’s Day, Too,” —she was one of the foot soldiers who helped Ronald Reagan to get where he was at the time. Ruthie kept a framed copy of that column in her office, and she treated it like the Shroud of Turin. Ruthie was part of that far-flung network of folks Dave talked to regularly to keep his finger on the pulse of what was going on in just about every state.

Jim Leach, former Iowa congressman: No one ever thought he had a slant, though he clearly had convictions.

Jack Germond: I never knew what his politics were.

Stephen Hess: I think he was about where moderate Republicans used to be.

Peter Hart: David was so measured. Ann is so unmeasured. She’s a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat, through and through a liberal. She always had her heart on her sleeve. David played all his cards close to his vest.

George Broder: For my brothers and me, while we were aware of who our father was, it was our mom who was actually the stronger imprinter of small-“d” democracy and activism and public service. Our earliest memories are of standing on Election Day handing out campaign literature or going down to the campaign headquarters and stuffing envelopes for a candidate. She served two four-year terms on the school board in Arlington County.

Dana Milbank: He would introduce Ann as “my first wife,” which I thought was terrific because they’d been married, what, 50 or 60 years.

Next: The Dean

THE DEAN

Maralee Schwartz: In 2003, the prescription-drug vote went till 6 in the morning. Other reporters peeled off. David never did. He stayed in the House gallery till 6 in the morning. Then he went home for a couple of hours. Then he came in at about 10 and wrote the most compelling tick-tock of what had happened. I remember sitting there reading it and thinking, “He puts all of us to shame.”

Colette Rhoney: I remember trying to get him to understand Facebook and what the Obama campaign was doing online. He didn’t stop wanting to learn.

Broder didn’t shy away from new technology, but he struggled with electronics on the road.

Maralee Schwartz: Filing [sending in stories to be edited] was just the nightmare of the century. I used to call Dan Balz’s room and say, “Dan, go in there and file David’s story.” And he’d say, “I have to file my own story.” I’d say, “File his first.”

Dan Balz: I joked that as long as David is here I had a job: his tech-support guy.

Maralee Schwartz: In 2004, during one of his “retirements,” I asked him to give me a list of some of the races he’d like to travel to and cover. I thought he could pick his spots and do a few stories. So he comes back with this list. I just sit there staring at it, and I went into his office and said, “David, we have to give the other reporters some opportunity to travel, too.” And he said, “Oh, right, right.”

George Broder: As his body did start to fizzle out on him, my mom drove him up to some of those precincts he liked to go to. They would go to a shopping center and sit on a bench, and he’d talk to voters. They’d drive up to Philadelphia, spend the day—four or five hours—and then drive back. Long day. Here they are, both in their late seventies.

Haynes Johnson: He never gave up, right to the very end. He was in and out of the wheelchair, in and out of the hospital. He had dialysis. But he kept going.

Maralee Schwartz: The last lunch I had with David was on September 19, 2010. He was ebullient. He had just been up to the Hill to see Dave Obey and John McCain. This was right when it appeared pretty certain Rahm Emanuel would leave his job to run for mayor of Chicago. David said, “So who do you think will be the next White House chief of staff?” I gave him the obvious list of names I’d been hearing. And he looked at me with a twinkle in his eye and said, “I think it’s going to be Bill Daley.” You didn’t hear that name for another three months until it was announced.

George Broder: Technically, he retired. He never retired. His last column was February 6. He left us March 9. The brain and the fingers worked fine right up until the very end. It was just the body that he put literally billions of miles on, that skinny little body. It carried him the whole time.

And he pushed it—how many all-nighters, how many 19-, 20-hour days, back to back, on the road, file the story, get back to the room, get up at 5:30 the next morning and do the Today show, and get on the bus.

This feature first appeared in the May 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.