Hundreds of Washingtonians left to join the Southern army. Confederate spies abounded in and around the government. When Congress ordered local officeholders to swear loyalty to the Union, Mayor Berret refused and was fired and arrested; after a month in jail at Fort Lafayette in New York harbor, he changed his mind and signed.

Lincoln suspended habeas corpus in nearby Maryland and ordered legislators arrested in order to block secession efforts there. While holding Maryland in the Union was essential to Washington’s existence as the nation’s capital, holding the other North-South border slave states–Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri–was a strategic necessity for winning the war.

Determined above all to save the Union, Lincoln also had to deal with rising Northern demands that he attack the root cause of the conflict. Francis W. Bird, another Massachusetts Republican, declared: “The key of the slave’s chain is now kept in the White House.”

During the first winter of the war, the President worked on several plans to test gradual, compensated emancipation in Delaware, which had fewer than 2,000 slaves. That trial balloon collapsed in the face of opposition there, but Lincoln persisted, and with support from Sumner and other leading abolitionists, on March 6, 1862, he sent a carefully drafted message to the Capitol.

He urged Congress to offer each state the “perfectly free choice” of accepting federal money to finance the gradual abolition of slavery. Change, he said, would come “gently as the dews of heaven.”

Northern reaction was broadly enthusiastic; the fiery abolitionist Wendell Phillips said the message was as surprising as “a thunderbolt in a clear sky.” But politicians from the border states, the only ones that would be immediately involved, said no. Out of the debate, however, emerged a bill to erase the stain from the nation’s capital.

Pushed in the Senate by future Vice President Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, it provided for immediate, compensated emancipation in the District. The bill ignored Lincoln’s wishes that it be gradual and require approval by local voters. It provided $1 million to pay owners who were loyal to the Union an average of about $300 for each slave freed by the act. A three-man commission would judge the loyalty of each owner and the value of individual slaves. The measure’s backers accepted an amendment that Lincoln strongly favored to provide a total of $100,000 for voluntary “colonization” of free African-Americans who chose to start new lives abroad.

By a vote of 29 to 14, the Senate approved the bill “for the release of certain persons held to service or labor in the District of Columbia.” Five days later, the House agreed, voting 93 to 39 in favor of it.

Lincoln promised that he would either sign or veto the bill promptly. He was concerned about popular reaction in the District because the bill would take effect immediately, without approval by local voters. The capital’s mayor and city aldermen opposed it; letters and petitions against it poured into the newspapers. The President worried over how freed slaves and their erstwhile owners would fare without each other’s service and protection. Maryland would remain a slave state until it adopted a new constitution in 1864–what would the city do with runaway slaves sure to flee into suddenly “free” Washington?

Meanwhile, he was slowly getting details from the great and costly battle at Shiloh, 700 miles away on the Tennessee River. In Virginia, General George McClellan’s army seemed bogged down around Yorktown, and Stonewall Jackson was bedeviling Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley. How would this sudden move against slavery affect the momentum of the war?

As Lincoln pondered, Senator Sumner and Bishop Payne came to the White House and spoke for all the abolitionists of the North, and for all the men and women held in bondage, when they insisted that this was a moral issue that should outweigh the political concerns that held Lincoln back.

In the end, Lincoln could not disagree. Finally, 150 years ago this April 16, he signed into law the bill that meant every resident of the District of Columbia was thenceforth and forever free.

In explaining why he did so, he was frank: “I have never doubted the constitutional authority of Congress to abolish Slavery in this District and I have ever desired to see the National Capital freed from the institution in some satisfactory way. Hence there has never been in my mind any question upon the subject except the one of expediency, arising in view of all the circumstances.” For a politician to say publicly that political expediency ever crossed his mind was not an everyday event in Washington.

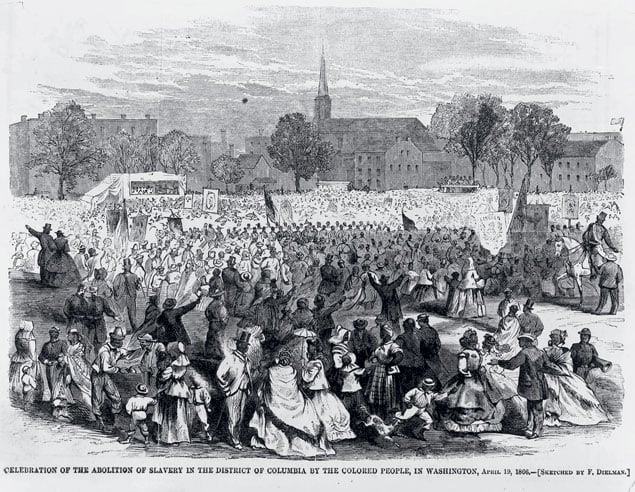

However he explained it, the President’s signature set off a rousing celebration among the black population–especially the hundreds who had hidden in fear of being carried beyond the District line to prevent their being freed. In black neighborhoods, the streets rang with happy music. The following Sunday in DC’s 17 African-American churches, preachers sermonized in thanksgiving and stirred spontaneous shouts of joy.

At the Colored (later Fifteenth Street) Presbyterian Church, religious leaders resolved that “by our industry, energy, moral deportment and character, we will prove ourselves worthy of the confidence reposed in us in making us free men.”

So emancipation became the law. But carrying out the rest of the act was another delicate political exercise.

First Lincoln had to nominate the three commissioners who would consider claims by former owners of the capital’s slaves. Two of them stirred no fuss–former Ohio congressman Samuel F. Vinton and Daniel R. Goodloe, a North Carolinian who had lived in Washington for decades and once edited the abolitionist National Era. The third was James Berret, the former DC mayor who had been fired and spent time in jail for refusing to swear allegiance to the Union. Lincoln picked him as a conciliatory gesture–he had already offered to appoint him a colonel, which the ex-mayor declined.

Berret’s nomination to the Emancipation Commission proved provocative: The New York Times asserted that it was “received by many Senators as highly offensive. . . . Is it possible that among all the sound, unsuspected men in the District of Columbia, some of whom patroled the streets of Washington night after night with carbines, to preserve the peace and protect the President, one year ago, not one can be found worthy of performing the duties assigned to the man who was one of the parties watched, and believed at that time to be an enemy to this Government? There is little doubt that the Senate will reject Berret.”

The Senate never had to make that decision. Whether Berret was still resentful toward Lincoln or expected to be voted down, or both, he refused this offer. Two weeks after the commission held its first session on April 28, Vinton had a stroke and died. To fill his place and Berret’s, Lincoln nominated former postmaster general Horatio King and John Brodhead of the Treasury Department.