Trish Vradenburg died suddenly of cardiac arrest in mid-April 2017. A television writer and playwright, Vrandenburg and her husband George were honored as Washingtonians of the Year in 2016 for their fight against Alzheimer’s disease. This 2012 profile of the couple by Shane Harris tells the story of how they joined the battle.

George Vradenburg stands in front of 800 people and tells them they are going to die.

It’s April 21, 2005. Vradenburg’s audience, in tuxedos and

evening gowns, fills the ballroom of the Grand Hyatt in downtown DC for

the second annual gala of the Alzheimer’s Association. Vradenburg, an

accomplished corporate lawyer who has just turned 62, is the gala cochair.

He’s a tall man. Commanding.

He draws an imaginary line down the middle of the room.

“Everyone on the right side, stand up,” he says. “Everyone on the other

side, stay seated.” The two camps look at each other. “All of you standing

will have Alzheimer’s disease by the age of 85. Those of you who are

sitting will be taking care of them.”

The audience has heard the statistics before, but not presented

so forcefully. They know that 5 million people in the United States have

Alzheimer’s and that the number will multiply as the baby boomers age.

They also know that the odds of developing Alzheimer’s doubles about every

five years after age 65. That by the year 2050 the annual cost of caring

for people with Alzheimer’s in the US will be more than $1 trillion,

enough to overwhelm Medicare and Medicaid. They know that Alzheimer’s is

the only major lethal disease for which there is no effective treatment,

prevention, or cure.

Yet those who are standing up might live longer with

Alzheimer’s than those who spend their life feeding, lifting, and

diapering a sick loved one. Look at the person pushing the wheelchair,

caretakers say. That’s who dies first.

Vradenburg is an appropriately solemn messenger for such grim

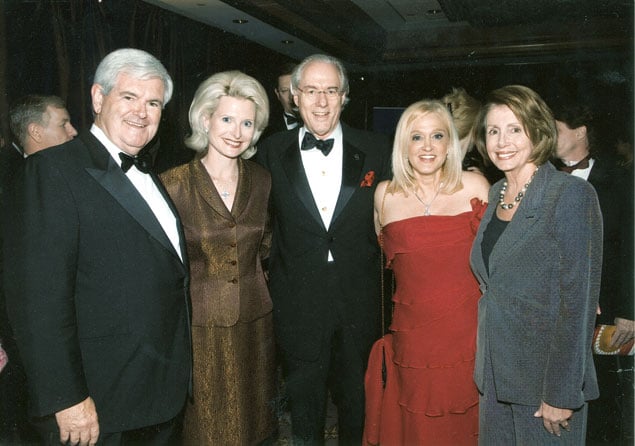

news. His wife, Trish, the blond woman in the red dress standing next to

him, the former sitcom writer—she’s the funny one. He leads with the hard

truth; she softens it with a well-timed line. “People ask me, ‘Who wants

to live to 85 anyway?’ ” she’ll say. “Eighty-four-year-olds!”

Trish Vradenburg, now 66, hopes to be so lucky. Her dream is to

die after getting hit by a truck, with just enough time to eat a frozen

Snickers bar before she goes. But she’ll settle for any ending other than

the one she’s imagined for the last two decades. The one she feels

trickling down her bloodline.

As the Vradenburgs stare through spotlights into a ballroom

full of people, half of them standing, half sitting, they know they might

as well be looking in a mirror. They know these odds. And they know they

aren’t good.

It was 1988. Trish and George Vradenburg were asleep in their

home in South Orange, New Jersey, a few miles from Trish’s mother,

Beatrice Lerner. At 3 am, the phone rang. “There’s a strange man here,”

Lerner said. “He’s trying to rob me.”

The drive took five minutes. George and Trish found Lerner’s

windows closed. Her door hadn’t been forced open, but she was on guard.

She pulled her daughter and son-in-law aside and whispered, “That’s him.

Who is he?” Lerner was pointing at her husband, Joseph.

After that night, she became more paranoid. And forgetful. And

quickly she, too, became unrecognizable.

One day Trish took a bad fall and called her mother to take her

to the hospital. The normally hypochondriacal Lerner—whom Trish could have

imagined driving the ambulance herself, all the while terrifying her

daughter with prognoses of infections and bone disease—arrived half an

hour later.

“Mom, we have to get to the hospital!” Trish said.

“All right,” her mother said casually. “Do you think they’ll

have tea there? How do you like my hat?”

Lerner had been among the most influential Democrats in New

Jersey. In photos lining a wall in George and Trish’s house, she stands

alongside John F. Kennedy, Harry Truman, Adlai Stevenson, Frank

Lautenberg, Bill Bradley, Jimmy Carter. In many of those photos, she’s the

only woman. A woman who once was on a list of Nixon White House enemies to

be investigated by the IRS.

Eventually Lerner forgot her own story. Her brain filled with a

normally beneficial protein that, in abundance, clumped in the space

between brain cells. The hardened plaque blocked transmissions among

synapses, the pathways the cells use to send commands that control the

body, memory, the senses. With the brain’s communications system jammed, a

second wave of attack arrived. Another protein, what scientists sometimes

call “the executioner,” burrowed into the weakened cells, destroying them

from the inside. Cell by dying cell, her brain shut down.

As the proteins flooded Lerner’s brain, her body went rigid.

She withered, immobile, in a New Jersey nursing home. By the time she died

in 1992, she’d been so long removed from the world that no one from her

storied political past remembered her anymore.

Watching her mother’s descent scared Trish. And watching it

scare Trish—seeing her wonder every time she misplaced her keys or her

cell phone—scared George. How many times can someone forget something

until the problem isn’t just forgetfulness?

George knows the disease isn’t just in Trish’s blood. It’s a

constant presence in her thoughts and in her sleep. She dreams about her

mother all the time.

The 2005 gala is supposed to be about triumph over that fear,

measured in the money George and Trish will raise—more than $1 million—and

in the personal affirmations the speakers will share. But Washington galas

blend into one another in a season crowded with fundraisers for diseases.

So when George goes off the usual script and puts the cold reality of the

numbers right in the center of the room, his words unnerve

people.

What no one knows yet on this night, not even George and Trish,

is that the Vradenburgs are about to start a movement. It will be fueled

by their fears and by an audacious goal: They plan to find a treatment or

a cure for Alzheimer’s in their lifetime.

George and Trish first met in November 1966, on a group date to

a Peter, Paul & Mary concert. She was a junior at Boston University.

He was a third-year law student at Harvard. Over drinks, she made what she

thought was a throwaway joke. He laughed hysterically.

Judging by his reaction, Trish thought George had never heard a

joke in his life.

She was dating one of his classmates, a fact George considered

only a modest obstacle. He offered her and her boyfriend a ride home and

dropped the guy off first. George and Trish talked for hours, and a few

days later he asked her out to dinner. On their third date he told her, “I

think we’re going to be married someday, but I don’t think you’re

persuaded of that yet.”

Trish thought: This man is nuts.

Her parents agreed. So did his. Joseph and Bea Lerner were

influential Jewish Democrats. George and Bee Vradenburg were Protestant

Republicans from Colorado Springs who traced their lineage to Peregrine

White, the first English child born in the New World, delivered aboard the

Mayflower while it was docked in Provincetown harbor.

“What’s his name again?” Mrs. Lerner asked Trish after their

first date.

“Vradenburg,” Trish said.

“B-E-R-G or B-U-R-G?”

“There must be different ways of spelling it,” her daughter

said. But then, on their second date, George asked Trish what she was

getting her mom for Christmas.

The Lerners came to Boston to meet the Colorado Republican who

was not a Jew.

“Your mother was crying all night,” Trish’s father told her.

“You’re killing her. Is that what you want to do?”

“Yes,” Trish replied. “That was my specific plan. To kill Mom.”

Bea Lerner went home, Trish says, “and put her head in the oven on ‘keep

warm.’ ”

George inundated Trish with love letters. She sent him a card

saying, “Soon, maybe not tomorrow, but soon.”

Bea Lerner and Bee Vradenburg joined forces to find a wedge

that they could drive between their children. “You generals can meet as

much as you want,” George told them. “But we privates are going to decide

how this war ends.”

George’s grandmother threatened to disinherit him of $1 million

if he married Trish. “It’s your money,” he said. “You make your choice.”

His grandmother backed down and finally consented to attend the ceremony,

but she refused to wear her real jewelry.

George understood why Trish’s parents wanted her to marry a

Jew. He, too, wanted his children to have a consistent spiritual

narrative, shared traditions. So he spent nearly a year studying Jewish

philosophy, customs, holidays, food. Along the way, he decided that any

people who had survived for millennia in the face of repeated efforts to

wipe them out and who managed to keep their culture and identity intact

must be here for a reason: Tikkun olam—to repair the world. It’s

the Jewish sense of spiritual purposefulness, and George wanted it in his

life, just as he wanted Trish. In November 1967, eight months before they

married, George converted to Judaism.

Whatever misgivings Bea Lerner had, George settled them. He

absorbed more knowledge of Judaism than anyone Trish knew in her family.

“He became a Jew to the max,” Trish says. And this must have moved her

mother. Because later, even in her near oblivion she would flirt with him.

She couldn’t remember herself or her daughter, but she somehow remembered

George. And he never forgot that.

George spent the first ten years of his law career at the

white-shoe firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore in New York City, then became

general counsel for CBS. He oversaw the successful defense of the network

in a landmark freedom-of-the-press case brought by General William

Westmoreland, who sued the network for libel over a 1982 documentary that

argued he had misled the President, Congress, and the public during the

Vietnam War. George also helped fend off a hostile takeover by media baron

Ted Turner in 1985.

Trish became a writer, penning humor columns for the Boston

Globe and the New York Daily News, a steamy romance novel

called Liberated Lady, a screenplay about a man frozen in ice for

20 years after his plane crashed in the Andes, which was optioned by

MGM.

While living in New Jersey, Trish enrolled in a writing class

at the New School in Manhattan. She sat next to an ex-writer from

Saturday Night Live who offered to send her ice-man script to the

producers of Kate & Allie, a new CBS sitcom shooting in the

city. They hired Trish to write a script, which the producers thought was

so good that it became the season-two opener. Trish always had an ear for

dialogue, even if she had trouble remembering names. (“I made my kids wear

name tags,” she says.)

Her work landed on the desk of Harry Thomason and Linda

Bloodworth-Thomason, old friends of the first family of Arkansas, Bill and

Hillary Clinton. The Thomasons hired Trish in 1986 for a two-week gig on

their CBS show Designing Women. The job ended up lasting the rest

of the season. Shuttling back and forth across the country, Trish found

herself in demand as a scriptwriter. At the high point of her career, she

was making as much money as her husband. But she turned down enticing

offers—even a seven-figure deal—so George and their two kids, Alissa and

Tyler, could stay back home while she remained bicoastal. “When my ship

came in,” she says, “I was at the airport.”

A few years later, Barry Diller, the chairman and CEO of Fox,

asked George to move to Los Angeles to help him build his growing company

into the fourth broadcast network. George and Trish decided to move. The

kids were older, and Trish’s mother was so firmly in the grip of

Alzheimer’s that she would never know her daughter was gone.

On January 22, 1992, Bea Lerner died in a convalescent home in

New Jersey. She was 76. The New York Times, which remembered her

as “a leader in Jewish, cultural, and charitable causes,” wanted to know

the cause of death.

There’s a euphemism people employ: “died after a long illness.”

It erases the last few messy years and protects a legacy. In the years to

come, Trish would hunt for the phrase in obituaries, and when she came

across it she was angry. She saw the disease hiding in people’s

houses.

Trish decided that if her mother’s death was to have any

meaning, she had to own it. So she started with the words. The

Times reported that Beatrice Lerner “died of complications from

Alzheimer’s disease.”

Trish wrote for four more years. On April 14, 1996, her play

The Apple Doesn’t Fall . . . opened on Broadway at the Lyceum

Theatre. It’s a punchy veiled memoir about a television producer and her

overbearing mother, who ladles out parental guilt and sitcom-worthy

one-liners as she succumbs to Alzheimer’s. An experimental drug brings the

mother back to lucidity long enough for an emotional reunion with her

daughter. Trish thought the play wasn’t ready. But she had a backer, and

her friends told her you don’t pass up a chance at Broadway.

The critics savaged it. FORGETTABLE COMEDY ABOUT ALZHEIMER’S IS

TRULY THE PITS, proclaimed the New York Daily News, Trish’s old

paper. “To write a comedy about Alzheimer’s disease suggests a lack of

taste, and Vradenburg lacks it in spades.”

“Ms. Vradenburg,” said the Times, “seems to have no

gift for finding the particular natures within generic types. [The

characters] are sitcom prototypes . . . .” The play was

“ghastly.”

It closed after one performance.

Trish thought the critics resented a TV writer’s presumption

that she could make it on Broadway. She was wounded by accusations that

she gave false hope to Alzheimer’s victims and their families. Didn’t they

read the papers? Didn’t they know there were promising drugs?

She decided to rewrite the script.

In 2002, when the play ran off-Broadway under the title

Surviving Grace, critics stomped on it again, for most of the

same reasons. But this time George saved it from the fate of its

predecessor. He paid for a $400,000 TV ad campaign—practically unheard of

for a small production with bad reviews. “It just doesn’t make sense,” the

general manager of the original production told the New York

Post, noting that the play had lost more than $1 million. Trish

replied, “I feel that no goal was ever achieved by fleeing.”

George was smoking cigars, drinking, and laughing with some of

his closest friends. It was June 23, 2001, the 60th-birthday party for Don

Flexner, a prominent Washington lawyer, at a friend’s house in Potomac. He

and Trish had left LA for DC after Steve Case, a cofounder of America

Online, asked George to be his general counsel and top

lobbyist.

George was with friends by the swimming pool when he felt

nauseated. He sat down to catch his breath. A few minutes passed and he

felt better. But then the nausea returned. George threw up and broke into

a sweat. He staggered into the living room and plopped down on a

chair.

Trish arrived at the party late; she’d been at the Kennedy

Center, where Surviving Grace was in previews before going to New

York. She poked her head into the living room and saw an old man slumped

on the couch. She moved closer and saw that it was George.

“Do you want to go to the hospital?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said.

George stood up and immediately collapsed on the

floor.

Some doctors at the party rushed to the living room. They

raised George’s feet up on a chair. “Is he comfortable?” someone

asked.

“He makes a nice living,” Trish deadpanned.

George stared up at her from the floor. “Even now?”

She shrugged. “Honey, it was a lay-up.”

The ambulance took George to Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in

Rockville. His heart rate was dropping. In the emergency room, a

cardiologist told him he had a blocked artery. They were going to give him

an anticoagulant.

Five minutes later, George overheard the doctor talking to

another physician. “The drug isn’t working,” he said. “I don’t know what

else to do.”

George beckoned the doctor. “My wife is the blond woman in the

waiting room. Find her and tell her that I love her.”

That’s the last thing he remembers. He woke up two weeks later

at a hospital in Virginia.

With George in a medically induced coma, Trish hid behind her

shield. “George is going to change his diet,” she told the Washington

Post’s Reliable Source. “Basically, we’re never letting him eat

again.” Ba-dum—tsh! “This is a helluva way to get publicity for

my play.”

Their grown son, Tyler, asked why she hadn’t cried. “I can’t

afford to cry,” she said. “When this is over, whatever happens, you’ll go

home and have your life. But Dad is my life.”

When George woke up, he found that his motor skills had

deteriorated. He tried to bring a spoon to his mouth but kept missing. He

had to learn to get up from a chair by pushing with his arms, not his

legs.

Lying in his hospital bed, George was startled by sudden

noises, a branch hitting the window. Every heart palpitation made him

wonder: Is this it?

He made a few decisions. He wouldn’t let a morning pass without

telling Trish he loved her. He would spend more time with his children—he

knew he had never been perfect in that regard. He had already charted his

exit from AOL, stepping down following the company’s merger with Time

Warner six months before the heart attack.

After cashing in his stock options, worth tens of millions,

George would never have to work again. He turned his energies to

nonprofits. He joined a regional planning commission for homeland security

after the 9/11 attacks. He was selected as chairman of the Phillips

Collection. He became an outspoken proponent of heart-disease

research.

George was 58 when he nearly died. He surveyed his achievements

and found that while he was proud of his contributions—to the First

Amendment, to building a television network, to the development of the

Internet—he hadn’t led those movements, nor had he really chosen them. As

he started getting used to the idea that one day his friends and family

would go on living without him, George decided he wanted to leave

footprints.

“I would like to repair the world before I go,” he says. “My

tombstone’s going to say, ‘I wasn’t finished.’ ”

In 2006, George and Trish sat in the Capitol Hill office of

Massachusetts representative Ed Markey, whom George knew from his work at

CBS and Fox. George and Trish had been asked to host the Alzheimer’s

Association gala for the third time, and they wanted to honor Markey with

an award.

That’s very nice, he told them, but Washington is full of

galas. If you really want to raise the money needed to find treatments or

a cure, you need to get Congress to allocate it. And that’s not going to

happen until we hear from the public. You have to form a political

movement. You have to become activists.

Markey, whose mother had died of Alzheimer’s, pointed to the

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, which was supported largely by the families of

sick children and had managed to elevate the profile of that disease. The

foundation invested in promising research from for-profit enterprises. It

raised money from private donors and in some cases by collecting royalties

on the sale of drugs developed under the foundation’s auspices. A team of

scientists supported by the foundation identified the gene that caused

cystic fibrosis, and virtually every drug available for treatment of the

disease was developed with the foundation’s support.

This model suited George and Trish. It spoke to his belief in

free enterprise and its capacity for innovation. And it was driven by

people who had been directly affected by the disease. That human element

resonated for Trish, who has always started discussions about Alzheimer’s

with the story of her mother.

George and Trish had never shied away from telling powerful

people what they should do. A few years earlier, Trish told Hillary

Clinton, then a senator from New York, that in the same week her mother

was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, the mother of Clinton’s old friend Linda

Bloodworth-Thomason was diagnosed with AIDS. She’d contracted HIV from a

blood transfusion.

“If that happened today,” Trish told Clinton, “her mother would

be living, but my mother would still die, because the HIV/AIDS people

raised their voice and demanded that something be done.” Trish wanted the

same consideration from Congress. “I don’t want a share of their pie. I

want a bigger pie.” Clinton agreed to help and cofounded a congressional

task force on Alzheimer’s. It eventually grew to 200 members.

But the money didn’t follow. And George and Trish knew they’d

have to find an awful lot of it. The National Institutes of Health spends

more than $5 billion a year on cancer research and around $3 billion each

on cardiovascular and heart disease and HIV/AIDS. Annual research on

Alzheimer’s comes to only about $400 million.

George remembered once hearing Newt Gingrich say that

Alzheimer’s, if left untreated, would overwhelm the federal budget. He

asked the former House speaker if he’d head up a study group to devise a

national recommendation for fighting the disease. Gingrich agreed and

asked former senator Bob Kerrey, with whom he’d once run a commission on

long-term care, to be his cochair.

A few weeks after Gingrich accepted, George and Trish were at a

dinner party at the home of Stephen Breyer, the Supreme Court justice.

Sandra Day O’Connor was there. She had retired from the court and was

spending more time in Arizona, where her husband of 54 years, John, was

dying of Alzheimer’s. George asked her to join the study group. She agreed

on the spot.

George assembled an army: Gingrich, Kerrey, and O’Connor were

joined by Mark McClellan, who had run Medicare and Medicaid in the George

W. Bush administration; David Satcher, the former surgeon general; Harold

Varmus, a Nobel Prize-winning cancer researcher; and others. The

Alzheimer’s Association helped with funding. So did George’s philanthropic

foundation; he was now putting his own money on the table.

The study group worked for two years. In 2009, it unveiled its

report before a special Senate committee on aging. “Our nation has no real

plan,” O’Connor said. A massive push was needed for prevention,

treatments, and a cure and to rein in the costs of caring for a swelling

elderly population.

The study group’s efforts led to legislation, the National

Alzheimer’s Project Act. On January 4, 2011, President Obama signed it. It

was the first major piece of Alzheimer’s legislation ever enacted. But

again, there was no money in it. The law gave the federal government the

mission to wage war on Alzheimer’s but didn’t supply the

ammunition.

So George and Trish opened another front.➝

As the bill wound its way through Congress, George and Trish

went door to door on Capitol Hill asking lawmakers to support another

piece of legislation, already written, called the Alzheimer’s Breakthrough

Act. It had first been introduced in 2004, 11 days after Ronald Reagan’s

death from the disease. It would allocate $2 billion for research into

Alzheimer’s—real money, the kind that would put it in the same league as

the other big killer diseases.

Trish visited Senator Carl Levin, the influential chairman of

the Armed Services Committee. “Everything George says is brilliant,” Levin

told her, but he wouldn’t support a bill that gave money to only one

disease. “I’m not disease-specific,” he said.

“But this specific disease will get you,” Trish said. “And it

will bankrupt this country.”

Levin was immovable.

“Okay,” Trish said. “I’ll camp outside your door until you

agree to support this. If you need me, you know where to find

me.”

No one told her that people don’t usually talk to senators that

way. When another senator told her he wanted the National Institutes of

Health to decide how to spend money, she asked, “If you can’t make a

decision, then why were you elected?”

Markey took up the bill in the House. And though it failed to

come up for a full vote, George and Trish personally secured the support

of 46 senators.

Whether they side with her or not, lawmakers don’t forget

Trish. When Maryland senator Barbara Mikulski, who agreed to sponsor the

bill, sees her in public, she points her finger and roars, “Alzheimer’s!”

When Levin, who never signed on, sees Trish in the halls or at a party, he

turns and walks the other way. Trish knows it’s a joke. But she also knows

he gets her now. He knows what she’s after.

Lawmakers came to respect George, too. Even to rely on him. At

a press conference recently introducing legislation to accelerate drug

research through a mix of government and private money, reporters asked

about patent law, clinical trials, and reducing the time it takes to get

new drugs to market. The four members of Congress standing with George

looked at one another, then at him. George stepped forward and answered

the questions.

Meryl Comer, a fellow activist and one of Trish’s closest

friends, sat next to her in the audience. Comer’s husband, who was a

department head at NIH, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s when he was 58.

Comer, a former TV journalist, has cared for him at home for 18 years. She

met George and Trish in year ten. They invited her to parties, saved a

seat at every table. “They saved my life,” she says.

Three years ago, with a camera from ABC’s Nightline

rolling, Comer read the results of a test that determined her risk for

developing Alzheimer’s. She has one of two genes known to increase the

risk of developing the disease. Her chance of getting Alzheimer’s is 30

percent higher than it is for someone without the genes. She may have

inherited it from her mother, who has also been diagnosed and lives with

Comer and her husband.

Meryl and Trish check in on each other. They talk about what

they’ve forgotten or misplaced. But on the subject of the test, they part

ways. Comer considers it a form of activism, a coming-out equivalent to

being tested for HIV. If doctors knew more about who had Alzheimer’s, she

says, they might be able to find treatments faster. So little is known

about how the genes involved work—how much family history matters, what

environmental factors might trigger the genes to start making surpluses of

the deadly protein.

But Trish refuses to get tested. Not until there’s a treatment.

If she’s dying, she doesn’t want to know.

At the press conference, the two women watched as George

answered every question, nailed every point.

“There’s never been a leader of this movement,” Comer says.

“Some claim it. But he is the one.”

On October 6, 2010, George and Trish, along with close friends,

two senators, Sandra Day O’Connor, and a few reporters, filed into a large

meeting room at Charlie Palmer Steak, steps from the Capitol. It was the

Washington launch of George and Trish’s new political organization,

started largely with their own money, called

USAgainstAlzheimer’s.

George delivered a variation on his stump speech, but there was

a new urgency, and anger beneath his normally placid eyes. “We intend to

have an impact in the 2012 presidential campaign,” he said, “and in the

races that year.”

The group has hired lobbyists and a public-relations team. It

has invited every current presidential candidate to address Alzheimer’s on

camera, and the three who did underscored, just as George does, the

long-term cost of the disease. This is political combat of a kind that the

national Alzheimer’s Association, as far as some of George and Trish’s

allies are concerned, has too long avoided.

George and Trish, who are registered respectively as Republican

and Democrat, are also spending their own money to fund political

campaigns and candidates who support their goal of finding a cure or

treatment. During the 2010 campaign cycle, they donated more than $150,000

to candidates of both parties, political-action committees, and campaign

committees. They’ve put almost as much toward 2012 races.

The Vradenburgs are rich. But not that rich. George’s windfall

from AOL was an eight-figure sum. Not nine or ten, like some of his former

coworkers. (Once, upon entering the $46-million home of AOL cofounder Jim

Kimsey, Trish turned to her fellow guests and asked, “Where’s the gift

shop?”) George and Trish can’t buy a cure for Alzheimer’s. Nor can they

rely on their own money to fund their cause the way Bill Gates has done

with malaria, allocating hundreds of millions of dollars through his

foundation. They have to leverage their money to encourage other private

donations and then use political pressure to get the federal government to

kick in the billions it will take to find new treatments and

preventions.

They’ve warned their son and daughter, now 38 and 41, “We’re

spending your inheritance.” They don’t mean it literally, but they don’t

plan on leaving their amassed wealth for their kids. When George hears

that some billionaire is leaving half his fortune to a cause, he thinks,

“You’re down to $500 million. Thank you. You should be taking yourself

down to $25 million or $50 million.”

George and Trish see their AOL money as the equivalent of

winning the lottery—they didn’t earn it the hard way. They don’t own boats

or planes. They have a home in Washington and an apartment in New York.

But their wealth is dwindling. In the span of a few years, they have spent

more than $6 million on Alzheimer’s and other causes.

They’ll make sure they retain enough to pay for their own

health care, and neither will ever let the other go to a nursing home. But

they don’t plan to die anytime soon. Instead, they’re setting a deadline.

USAgainstAlzheimer’s intends to find treatments, prevention, or a cure for

the disease by 2020.

If George is really honest, he knows this goal is probably

unachievable. But he believes—always has—that without a goal there’s no

progress. And if anyone’s doing the math—as George has done, many times—in

2020, Trish, by then entering her mid-seventies, would be in the window of

high risk for developing Alzheimer’s. If she isn’t already

there.

“I lost my BlackBerry again,” Trish says.

“So that’s why you’re not taking my calls,” George says. This

time it’s his turn to bring the levity. But these moments of ordinary

forgetfulness are uncertain harbingers. The branch rattling against the

window again.

George rarely betrays his fears. He works Washington with equal

parts charm and authority. Members of Congress greet him like an

ambassador. A few months ago, George and Trish showed up five minutes late

for a meeting with Nancy Pelosi, but she welcomed them with hugs and

two-cheek kisses. What was supposed to be a 15-minute meeting lasted

39.

In meetings like this, George gives the policy briefing and

lays out the strategy. Trish is all tactics. “How do we get more

Republicans?” she asks. Under pressure from Tea Party activists and

deficit hawks, Republicans won’t sign onto any legislation that increases

funding without a comparable reduction in spending elsewhere. Democrats

have been more willing to sign on to legislation, but without Republican

backing it’s largely a token gesture.

George tells Republicans that Alzheimer’s will bankrupt the

federal government—but if you invest in a cure now, you’ll save

trillions.

In truth, any number of illnesses—including heart disease,

which nearly killed George—could overwhelm government health-care

spending. But Alzheimer’s is the only one that’s untreatable. George is

losing patience with both sides as they argue about reform of the

health-care system: “Lost in this whole debate is that the traditional way

we’ve driven down health-care costs in the 20th century is to cure

disease! No one talks about the fact that you don’t have polio-care costs

anymore.”

He has mastered not just the politics of the disease but the

science. The proteins and the genes, how they interact and how they don’t.

He defines the gap between the known and the unknown and looks for ways to

fill it. He tracks potential drug treatments in the pipeline. He consults

with public-health officials. Befriends leading researchers.

“I can e-mail with George back and forth like I do with a

scientist,” says Rudy Tanzi, who co-discovered the genes that cause

early-onset Alzheimer’s, the rarest form. “He’d be qualified to work in my

lab.” Tanzi credits George and Trish’s efforts for galvanizing researchers

and in the process “increasing public awareness about Alzheimer’s by 1,000

percent.”

Trish is the indispensable partner. The right brain to George’s

left. Proof that his interest is beyond scientific or

political.

It’s March 2002. Trish sits in the darkened Union Square

Theatre in New York, visiting with her mother. She does this once a day.

Twice if there’s a matinee. Doris Belack, a veteran TV actress, stands in

for Bea Lerner. The audience thinks it’s watching a woman named

Grace.

Trish’s play will survive longer off-Broadway—three months

instead of one night. George’s advertising campaign helps. Some people say

they see their mothers onstage.

Trish’s favorite scene comes after Grace takes the experimental

drug and momentarily slips free of Alzheimer’s. She has booked a pair of

cross-country tickets and planned a vacation to the Grand Canyon with her

daughter, Kate. “We leave tomorrow,” she says.

Kate: “We? I’ve got an important job.”

Grace: “Writing punch lines, Katie. I mean, let’s face it,

you’re not exactly Arthur Miller. Quit.”

Kate: “Quit??! There’s no way I’m going to—I’ve worked years to

get . . . .”

Grace: “How many people would give anything to have their

mother back? When you think about it, I’m giving you a gift.”

Trish says she wrote the play to tell people about Alzheimer’s.

And that’s true. But it was also a present to herself.

She entertains notions of reviving the play again. Mostly,

though, she limits her writing to blog entries—and checks. As she gets

older, she thinks more than she used to about getting Alzheimer’s. She

says the next big invention should be GPS tracking for personal items—the

phone, the keys. She makes a more conscious note of where she puts things.

But she still won’t get the genetic test.

Last year, George got a seat on an advisory council writing a

national plan to combat Alzheimer’s. The council was created by the law

Obama signed in 2011, the one based on George’s study group. The plan,

finalized in May, will become the guiding policy strategy for the

administration, which has committed to spending $156 million more on

Alzheimer’s research over the next two years. It’s a trifling amount, but

a start. The plan contains five goals. Number 1: Prevent and treat

Alzheimer’s disease—by 2025. Without George’s urging, it wouldn’t have

included a deadline. Publicly, he takes no credit. But he leaves a

footprint.

As George thinks about his own mortality, he considers what

Trish would do without him. She’d have plenty of money. She’d probably

move closer to one of the kids. Tyler is in Chicago, teaching and coaching

high-school football. Alissa is a lawyer and talent manager in Los

Angeles. George thinks Trish would carry on.

It’s when he thinks about living without her that his mind goes

somewhere he can’t linger. He thinks about 2020, or 2025, and sees Trish.

And she’s not alone. She’s surrounded by 10 million other people. They

didn’t beat the odds, either. And this drives him.

“I can’t do anything for her,” he says, “until I do it for

everybody.”

Looking for help and support with Alzheimer’s Disease in Washington? Consult our list of resources.

This article appears in the June 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.