Todd Schneider didn’t like the first table the maître d’ showed us.

It was on the patio at Indigo Restaurant, right by the main entrance, and would leave Schneider exposed to gawkers on Las Olas Boulevard, Fort Lauderdale’s Rodeo Drive—not ideal for a guy who decided he needed to go into hiding more than a year ago.

“Maybe something more private?” he suggested.

The maître d’ took us to the far end of the patio, a spot partially shielded by a palm tree and more to Schneider’s liking. He sat down and started talking before even opening his menu, eager to get started: “How the hell did I get caught up in all this? That’s the million-dollar question.”

Each time the waiter came by for our orders, Schneider told him we needed a couple of minutes. “He’s interviewing me,” he announced to the server.

“I thought you looked familiar,” the waiter said. “I’ve seen you on TV.”

Schneider laughed. “Maybe on America’s Most Wanted.”

“No, no. It was MSNBC, something political.”

None of us knew what to say.

Then it clicked. The crisp white shirt, the close-shaved but definitely balding head, the salt-and-pepper scruff: Schneider was a dead ringer for one of Washington’s best-known political bloggers.

“He’s not Andrew Sullivan,” I said.

“Huh,” the waiter said. “You do look like him, though.”

Schneider looked disappointed as the waiter walked away.

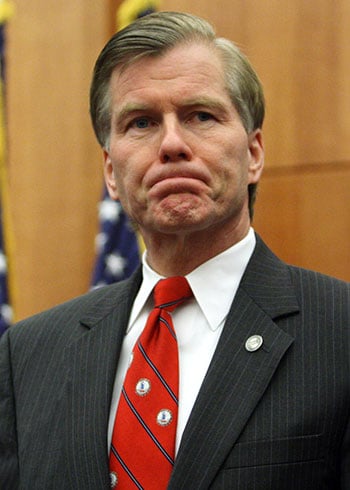

You don’t have to remind Bob McDonnell who Schneider is. Before Virginia’s 71st governor got crossways with his onetime executive chef, McDonnell was the Great Republican Hope. His win in 2009 snapped a four-year losing streak for the GOP in statewide elections, and after taking power in 2010 he wasted no time establishing himself as a conservative who could cut deals with Democrats. Mitt Romney considered him for the vice-presidential ticket in 2012, and pundits called him a credible contender for the White House in 2016.

Today the McDonnell brand is toast. As the governor departs Richmond, federal authorities are reportedly probing his relationship with an executive who gave him and his family gifts and loans totaling more than $160,000. The executive, Jonnie Williams, reportedly bankrolled a McDonnell daughter’s wedding, bought the governor a $6,500 Rolex, and financed a shopping spree in New York City for his wife, Maureen. According to the Washington Post, federal prosecutors will decide soon whether to indict McDonnell and his wife. The allegations have turned the once squeaky-clean governor into a political punch line and helped sink the gubernatorial bid of Tea Party golden boy Ken Cuccinelli.

What began with some groceries missing from the governor’s kitchen has snowballed into the biggest—and most unlikely—political scandal to hit Virginia in decades.

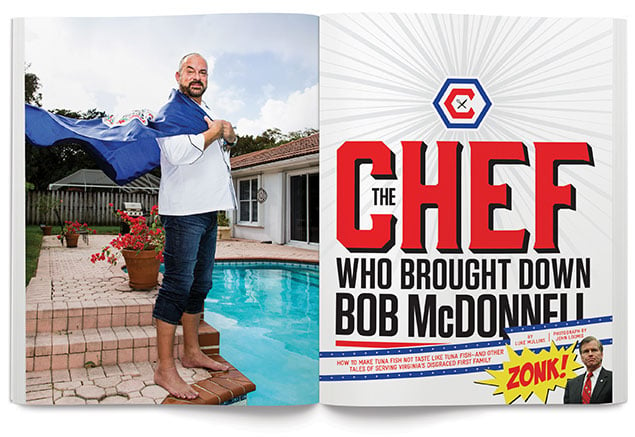

And it all started with the man sitting in front of me: Todd Schneider, the chef who took down the governor. A man with a checkered past of his own.

“You have to remember,” Schneider told me, “everybody talks in the kitchen.”

• • •

After arriving at Virginia’s executive mansion in 2010, Schneider quickly became familiar with the first family’s tastes. McDonnell was a pasta man. “He didn’t have an upscale palate,” the chef says. “You could give him Prego and he’d be happy.” First lady Maureen McDonnell was more eclectic—her preferences included Mexican food, crab-seasoned popcorn, and “tuna fish that doesn’t taste like tuna fish,” which Schneider prepared by swapping carrots and celery for mayonnaise.

The McDonnells made the new chef feel like part of the family, Schneider says. Maureen and one or more of the couple’s five adult children often gathered in the kitchen to chat with him as he made dinner, and the governor occasionally stopped by to crack open a Corona. Above Schneider’s stove, the first lady hung a sign reading “Here’s the Cook Who Serves Love and Laughter.” Once, she asked if he would come to Washington with them should her husband become Vice President.

Schneider found McDonnell friendly enough. But he didn’t much care for how thick the boss tended to pour on praise. “I’m the best-fed governor in America,” McDonnell liked to say.

“When you get out of politics,” Schneider once told him, “you’d make a good used-car salesman.”

The chef was less fond of Cuccinelli, Virginia’s attorney general. “He’s got the personality of a stone, and he talks forever. I’d sit there and I’d be like, ‘Oh, my God—will you just be quiet?’ ”

Tension between McDonnell and Cuccinelli was clearly visible to the staff. “They wouldn’t talk to each other,” Schneider says. “As soon as they took a picture together, they would take off to opposite places in the room.”

But the most powerful force in the executive mansion wasn’t the back-slapping governor or his outspoken AG—it was the first lady.

Schneider says he became especially close with Maureen, a former Redskins cheerleader from Fairfax County. She spent so much time in the kitchen that he kept a barstool around so she could have a glass of wine and relax as they talked. Maureen had few friends and was lonely in the mansion, Schneider says. “I didn’t ask for this job,” she told him.

Although Maureen could be charming and fun, he says she had a “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” personality. For one thing, she insisted the house be kept just so—if a bed wasn’t made to her satisfaction, the first lady would untidy the sheets so the maids had to start over. And Maureen infuriated the mansion staff by ordering employees to run her personal errands at all hours, Schneider says. He received text messages from her as late as 2 AM instructing him to fetch everything from liquor to tampons, and he’d be “browbeaten” for returning without the exact items she demanded, he says.

“Have you ever gone and bought tampons?” Schneider asks me. “There’s a million different kinds of them.”

Things got so bad that the first lady’s chief of staff finally told employees to shut off their state-issued BlackBerrys at 10 PM so Maureen couldn’t hassle them, Schneider says.

She could be downright nasty to subordinates. “If the first lady did not get her way, she pouted, screamed, yelled,” Schneider says. “She would swear at you and call you names.”

He once saw the mansion director in tears after the first lady cussed her out. The chef says he pulled Maureen into a kitchen closet. “You cannot talk to people this way,” he recalls saying. “You’re the first lady of the Commonwealth.”

“But she is a stupid bitch,” the first lady said, according to Schneider.

The staff grew to despise the governor’s wife; several maids quit and the butler refused to speak to her, Schneider says. Employees eventually drafted a letter to McDonnell threatening to resign en masse if their treatment didn’t improve. “Bottom line is she had issues,” the chef says.

Maureen’s chief of staff told the employees that part of their job was to keep the first lady happy so she’d stay out of McDonnell’s hair, according to Schneider. “The governor could not handle his wife,” he says. “We all knew that.”

He describes the first family as always up for a party. “These people like to drink—a lot,” he says. “We’d come back on Monday and all the liquor was gone, all the food was gone.”

The McDonnell children who didn’t live at the mansion removed “cases and cases” of Gatorade, soda, and bottled water from the kitchen, Schneider says. When the family’s twin sons moved out of their dorm at the University of Virginia, the first lady helped herself to mansion supplies in order to furnish their apartment, he says. “I’d be like, ‘I’m missing half my pots and pans.’ ”

He saw one daughter take drinking glasses with the state seal on them, while another left with boxes of unused trash bags. According to Schneider, she said, “Why should I pay for it?”

“Those people, they just had their hands in the cookie jar the whole time,” he says.

“We are not going to comment on allegations from a fired former disgruntled employee,” says Jason Miyares, a spokesman for the governor’s legal team.

• • •

Schneider is great fun to talk to, full of gossip and drama, and beloved by friends for his big personality. Verifying the things he tells you, however, is less entertaining.

He grew up in Westport, Connecticut, and says he “got the food bug” while working for the catering company of his hometown celebrity, Martha Stewart. But a Stewart spokeswoman couldn’t confirm that Martha ever employed Schneider. The chef says he studied at New York University before becoming a Wall Street bond trader and running his own catering company on weekends. NYU has no record of Schneider’s attendance, according to a university spokesman.

In the late 1990s, he worked as an administrator for Ronald Merrell, who chaired the surgery department at Yale School of Medicine, Merrell says. When the doctor was hired by Virginia Commonwealth University in 1999, he took Schneider to Richmond with him.

Records show that Schneider was charged with felony embezzlement in 2000; according to the AP, he pleaded guilty to a reduced charge. Merrell says Schneider used university funds to buy plane tickets for himself. When I asked the chef about the arrest, he denied it—must be a different Todd Schneider, he told me.

Merrell said I had the right guy. “Same Todd Schneider,” he wrote in an e-mail. “I really hated it but [it] really was something for the Commonwealth Attorney to act upon.”

Schneider started over, launching Seasonings Fine Catering & Event Planning in Richmond. Before long, he was making hors d’oeuvres for the city’s elite. Mary Shea Sutherland, then working for an event-planning firm, hired Schneider for the Richmond premiere of the 2003 Civil War film Gods and Generals, starring Robert Duvall. “Perfection” is how she describes Schneider’s work. “When I hired Todd, I never had to worry.”

Schneider became toque to the Virginia political establishment, catering events for former governor Tim Kaine, Republican House majority leader Eric Cantor, and Terry McAuliffe, the incoming Virginia governor. The White House came calling in 2007, and the chef cooked for George W. Bush’s Thanksgiving address, according to Sutherland. The following year, it was the Obama campaign that needed him for an event.

“He was the caterer to the stars,” says Pat Sarver, a Richmond resident who hired Schneider for her daughter’s wedding and remains his friend.

Maureen McDonnell was the one who wanted Schneider in the first family’s kitchen, Sutherland says. “She said, ‘Do you think he’d come?’ ”

Schneider wasn’t interested at first. He was running a restaurant along with his catering company and felt too busy for the $60,000-a-year job. But the more he thought about it, the high-profile assignment seemed impossible to resist.

He brought more than his recipes. Schneider took with him a public record that, along with the embezzlement arrest, included $400,000-plus in state and federal tax liens. The chef blames his tax problems on the financial mismanagement of his former business partner.

How on earth did someone with Schneider’s past get into the governor’s kitchen?

A spokesman for McDonnell has called it a mistake, saying the state never ran a background check on Schneider.

The chef disputes this claim.

During an early phone conversation we had, he insisted he cleared a background investigation and had the documents to prove it. Days later, I received his evidence: a February 2010 e-mail from the mansion director to Schneider.

The message was almost entirely redacted in black marker. Of the three lines of text, only the hello, the goodbye, and the phrase “have been cleared via background check” were visible.

It was so sketchy that I worried I’d been duped. I bought a plane ticket to Florida.

• • •

Schneider met me outside an art gallery on Las Olas Boulevard one afternoon last fall. To my relief, it was the same guy I’d seen in the papers.

He didn’t know much about the strip’s restaurant scene, and it took us a few minutes to settle on the patio at Indigo. Once he got situated, the chef was anxious to finally explain himself. And the way he tells it, McDonnell isn’t the only victim of this whole mess. “They basically destroyed my life,” Schneider says.

It was 2011 when Jonnie Williams became a regular at the governor’s mansion. At first, he showed up only during business hours, but before long Williams was also getting together with the McDonnells on evenings and weekends, Schneider says. The chef found it curious that the first family treated Williams—then CEO of a struggling Virginia dietary-supplement maker named Star Scientific—with such deference. “Everyone acted like he was the Prince of Wales,” as Schneider puts it.

Before the first lady flew to a meeting of doctors and investors in Florida, where she spoke favorably about one of Star Scientific’s new pills, she asked Schneider to bake a batch of oatmeal-raisin cookies—Williams’s favorite—so she could deliver them to the executive. To toast the pill’s launch, Maureen hosted a luncheon at the mansion that Schneider prepared and the governor attended. The first lady even suggested that Schneider buy Star Scientific stock. The chef never became a shareholder, but he did take the company’s new pill—an anti-inflammatory supplement—for about a month. “It didn’t do anything for me,” he says.

The chef noticed that Williams was becoming increasingly generous toward the first family. Golf clubs from Williams appeared at the mansion, a gift for the McDonnell sons, Schneider says. Williams’s $190,000 white Ferrari convertible was often parked outside; according to the Post, the McDonnells borrowed it to get back to Richmond after a stay at Williams’s lake house near Roanoke. And Maureen showed the staff a new Rolex she claimed to have bought for her husband. “Nobody believed her,” Schneider says.

Meanwhile, in June 2011, Schneider’s company catered the wedding of one of the McDonnells’ daughters in the mansion’s garden. “They all drank and got drunk like crazy,” he says. The family was having so much fun that Maureen asked to extend the reception. Later, she refused to pick up the extra costs, Schneider says, and she never tipped the staff.

By now, everyone in Virginia knows the McDonnells didn’t end up spending a dime on the jumbo shrimp or London broil the 200 guests were served; it was Williams who paid the $15,000 bill.

Schneider overheard other staffers speculating that McDonnell’s relationship with Williams might not be aboveboard, and the chef was already concerned that goods were being lifted from the kitchen. “There was just too much weird stuff,” he says. He brought his concerns to the mansion director and the first lady’s chief of staff. “They said, ‘Cover your butt, Todd.’ ”

Schneider began documenting everything. He took cell-phone pictures of anything he thought looked fishy and made sure to preserve Williams’s wedding check to his catering company. “If they ever come after me, I’m going to sing like a canary,” the chef recalls telling the mansion director.

On February 10, 2012, a loud banging on Schneider’s door jolted him awake. Two men were on his porch: “I thought, ‘Why are there salesmen at my door at 7:30 in the morning?’ ”

But this wasn’t a sales call.

Someone had called an anonymous tip in to a state hotline for waste, fraud, and abuse and claimed that Schneider had stolen food from the governor’s mansion. Now the FBI and state police were at the chef’s door, ready to question him.

Schneider wasn’t concerned. There was a simple explanation for everything, he said.

In addition to cooking the first family’s meals, Virginia’s executive chef is expected to cater official events at the mansion. But the house didn’t always have enough linens, silverware, or chairs, Schneider says. When he came up short on supplies, he’d order them from his company and bill the state.

The state, however, refused to pay the invoices, court records show. Handing contracts to state-employee-owned companies could present a conflict of interest. As a work-around, the mansion director compensated Schneider by letting him use the house’s account to order food, which he could then use at his restaurant or catering company, he says.

Unconventional though the arrangement may sound, Schneider’s story holds up—court documents substantiate it. The chef told the agents who came to his house that he’d carted off mansion food, but only as part of this barter agreement. When they left later that morning, he figured the matter was settled.

“I just had the FBI and the state police come to my house,” he told the mansion director when he got to work.

“Did you tell them about our arrangement?” she responded, according to Schneider. (The mansion director didn’t reply to requests for comment.)

“I did.”

That afternoon, the governor’s chief of staff and the state police cornered Schneider in the kitchen. “We are putting you on paid suspension,” the chief of staff told the chef, according to Schneider. The men escorted him off the grounds and watched him drive away.

Days later, armed federal and state law-enforcement agents raided Schneider’s catering company and found an assortment of items he’d taken from the mansion. The loot, he says, included food, a cooler, and toothpicks.

Schneider felt betrayed by Maureen and Bob McDonnell. The chef considered himself a surrogate family member and couldn’t believe the couple wouldn’t help resolve what he considered an honest misunderstanding: “I was hurt.”

He wasn’t about to go quietly.

• • •

On March 8, 2012, Schneider showed up at the Virginia attorney general’s office with the stack of documents he’d compiled during his time at the mansion. A copy of the $15,000 wedding check from Williams was in the file along with pictures of Costco-size hauls of snacks the McDonnell kids had lifted from the mansion.

“We [showed] them everything,” Schneider says.

Steve Benjamin, Schneider’s attorney, left the meeting thinking the investigation was over. The chef had coughed up valuable information the authorities could use to pursue a public-corruption case against a bigger target—the Virginia governor himself.

Two weeks later, the FBI and Virginia state police asked Benjamin for Schneider’s stash of records. Among other things, he turned over the $15,000 wedding check that’s now at the center of the federal investigation into the McDonnells.

The allegations were enough to ruin him. Although he hadn’t been charged with a crime, Schneider says clients stopped calling and friends turned their backs. His businesses went under, and his house went into foreclosure. “I was the leper of Richmond,” he says.

After his father died suddenly, Schneider fled Virginia and went into his self-imposed exile in Florida. “Here I am 51 years old and I’ve got to go live with my mother,” he says.

She passed away not long after, and he fell into a depression, spending days crying alone in his house and drinking a couple of bottles of wine every night. It got so bad that his friend David Evans worried the chef might kill himself. “He said, ‘I don’t know if I can deal with this anymore,’ ” Evans recalls. He went to Florida and found Schneider emaciated, with dark circles under his eyes.

In March 2013, Benjamin, Schneider’s attorney, got word that Cuccinelli was getting ready to indict the chef despite all the damaging information he’d given to the government. Stunned, Benjamin did some investigating of his own. He went through Cuccinelli’s financial disclosures and discovered that the attorney general had used Williams’s vacation home—free of charge—and owned thousands of dollars’ worth of Star Scientific stock in 2012. “You can’t indict Todd Schneider, because your office has an irreconcilable conflict of interest,” Benjamin says he told one of Cuccinelli’s deputies.

But the attorney general didn’t back down—he got a grand jury to indict Schneider on four counts of felony embezzlement for stealing food from the mansion. According to court papers, there was indeed a barter agreement between the mansion and Schneider, but how long that agreement was supposed to last is in dispute.

The chef spent his half day in jail wearing a blue blazer, a white button-down, and a tie. “What’s the lawyer doing here?” a prisoner joked. Lunch was a slice of ham and two pieces of bread.

It’s unclear why Cuccinelli went ahead with the case, knowing the chef had the goods on the governor. “I think they thought that by [indicting me] it would shut me up,” the chef says. “It didn’t.”

In the coming months, the dirt came out. After the state refused to drop the charges against Schneider, all the petty details—the free wedding reception, the Rolex, the pilfered water bottles—found their way into the Washington Post and other newspapers from Richmond to DC.

In September 2013—when Cuccinelli had just weeks to go until the election—the state allowed Schneider to plead no contest to two misdemeanor counts of embezzlement. He was spared jail time and was ordered to repay the value of the goods he admitted taking.

The whopping total: $2,300.

Schneider may get carried away with some of his stories, and finances obviously aren’t his forte, and yes, he has a criminal record, but the thrust of his allegations of wrongdoing in the mansion is substantiated by records—records now in the hands of federal investigators.

Because of Todd Schneider, Bob McDonnell is not going to the White House.

For the others caught up in The Commonwealth of Virginia v. Todd Schneider, things didn’t work out so well, either. Cuccinelli lost his race to Terry McAuliffe. Williams resigned from Star Scientific. And Greg Underwood, the special prosecutor who handled Schneider’s case, was arrested for drunk driving.

Says Schneider: “Karma is a bitch.”

• • •

After lunch, Schneider took me to a nearby beach, plopped onto the sand, and explained that he used to visit the spot to clear his head when pressure from the investigation became too much.

These days, Schneider has a lot less on his mind. Nearly two years after leaving the mansion, he’s back in the food business and recently got a job as an event planner.

Not that he expects to be throwing parties forever.

For one thing, there’s a book in the works. It’ll be about his tangle with the McDonnells, and Schneider hopes it’ll bring in enough cash to cover $100,000 in legal bills. He can already see the movie version, with Meryl Streep as Maureen and Billy Bob Thornton as the governor.

He also says he has additional, and equally unflattering, info on the governor. He plans on keeping it private—unless Virginia comes after him again.

Before all this, Schneider didn’t pay much attention to the news. These days, the first thing he does every morning is scour the internet for the latest developments in Virginia’s so-called gifts scandal. His favorite places to browse are the comments sections of political blogs, where every so often a reader will point out the real lesson of McDonnell’s downfall: “Never mess with the chef.”

Senior writer Luke Mullins can be reached at lmullins@washingtonian.com. Editorial intern Will Grunewald contributed reporting.

This article appears in the February 2014 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)