Walking into the Sorenson Language and Communication Center at Gallaudet University in Northeast DC can feel, at first, like walking into any new academic building on any American college campus.

Students chat away as the doors slide open. They carry their laptops and backpacks into an atrium. They catch sight of friends walking on upper floors and greet them.

The building starts to seem a lot more remarkable, though, when you tour it with Hansel Bauman, the university architect at Gallaudet, America’s only liberal-arts college for the deaf and hard of hearing. It’s the little things that are different: Bauman points out the wide entryways that allow signers more room to gesture and the automatic doors that don’t require anyone to stop mid-phrase to grab a handle. In the common room, a large, horseshoe-shaped bench fosters the kind of “conversation circles” in which deaf people feel comfortable. Diffuse natural light makes it easy to follow friends’ and teachers’ signing.

Bauman and Gallaudet have a name for this kind of architecture: DeafSpace.

DeafSpace has made Gallaudet stand out even in a local university scene undergoing a remarkable real-estate boom: George Washington University has been expanding south and east from its Foggy Bottom neighborhood. Georgetown built a sleek new School of Continuing Studies on Massachusetts Avenue near Gallery Place. None, though, is doing as much creative thinking about urban design as Gallaudet.

With an endowment that, at less than $200 million, is a fraction of Georgetown’s or GW’s, Gallaudet has been pushing at the borders of design since 2008, with a group of new buildings that address the ways deaf people perceive their environment and interact.

The architectural changes also represent a broader philosophical shift, in which architects are concerned less with conforming to rules about handicapped access than with designing more creatively for all kinds of people—rethinking mundane parts of our everyday environment such as the width of a sidewalk or the arrangement of desks in a classroom.

Meanwhile, the area around the 151-year-old university is becoming hot, forcing the school to ask questions that might have been hard to fathom when nearby Trinidad was known for its drug-war-era crime: How can Gallaudet extend its presence beyond the gates in a way that’s in sync with its design and culture?

In September, the university launched an international competition to create a new entrance to its campus that would integrate the school into the city. The four finalists, announced in October, have one thing in common: They have zero built work in Washington. And not one is a usual firm on the local higher-ed radar.

Whoever wins the competition will enter a conversation that’s changing accessible design.

“We tend to think it’s about ramps and elevators,” says Sara Hendren, a professor at Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts who has followed the evolution of DeafSpace. “But it isn’t ticking off a laundry list of compliance-based rules to avoid being sued, but actually thinking: What could architecture do?”

Gallaudet’s new construction, Hendren says, “does something with architecture that we tend to think architecture isn’t for.”

Gallaudet has an enviable design pedigree.

Its 99-acre campus was laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, landscape architects responsible for New York’s Central Park. (Olmsted also designed the US Capitol grounds.)

Gallaudet doesn’t have an architecture school, but in 2005—spurred by a $5-million donation for a new linguistics-and-language-skills building—30 or so professors and students began meeting to discuss how deaf people experience physical space. “We knew what we didn’t want, but we weren’t sure what we wanted,” remembers MJ Bienvenu, a Gallaudet alum who teaches American Sign Language (ASL) and deaf studies at the school.

Dirksen Bauman, chair of Gallaudet’s Department of American Sign Language and Deaf Studies, introduced his brother Hansel to the group. (Both men are hearing.) Hansel Bauman, then a freelance architect, had spent the previous few years working on industrial- and scientific-research buildings at a firm in San Francisco. He had never designed anything for the deaf but had often focused on the personal experience of researchers in his science-lab designs rather than big expressions of architectural form—an inside-out approach that would serve him well at Gallaudet.

In fall of 2006, the Baumans and another professor, Ben Bahan, started co-teaching a class in the university’s Department of ASL and Deaf Studies about the idea of DeafSpace. Students analyzed dorms on campus, looking at how they did or didn’t support deaf interaction and identifying basic principles. Although English is widely spoken on campus, American Sign Language is the dominant mode of communication. Both visual and kinetic, it requires a wide field of visibility and clear lines of sight. (Deaf homeowners often cut holes in walls to communicate between rooms.)

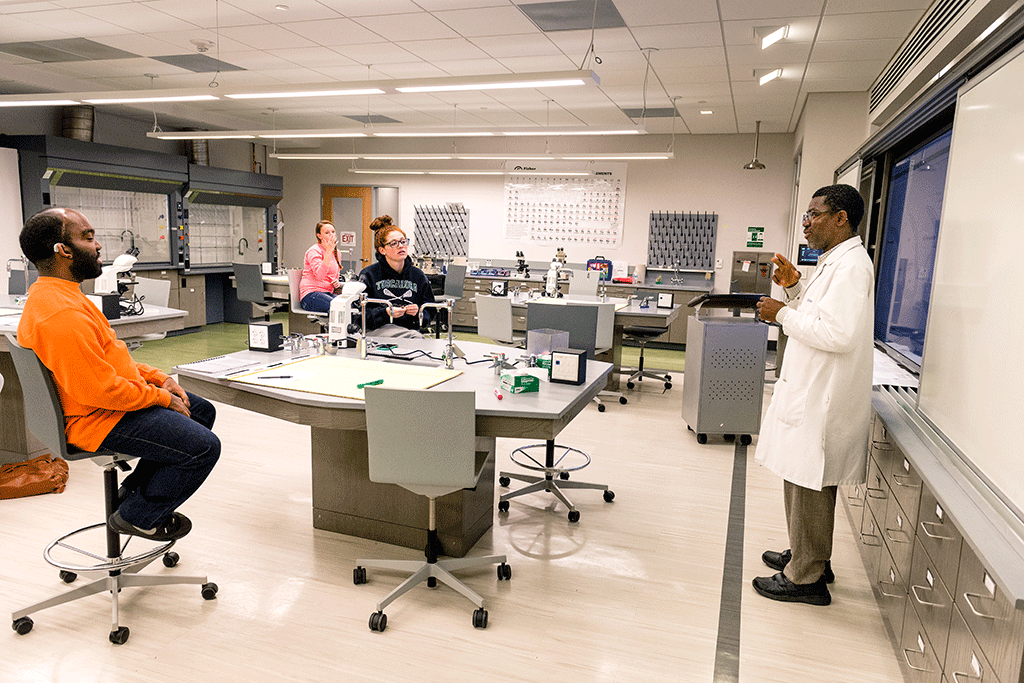

The students studied classrooms as well and determined that certain common seating arrangements—such as long, straight benches or rows of chairs—don’t really work. Soft, diffuse lighting is crucial, as glare or dimness strains the eyes, further dissuading a student at the end of a long day (or recovering from a long night) from following a signed discussion. Acoustics matter, too: Students who use hearing aids or cochlear implants are bothered by echoes.

These early explorations of DeafSpace coincided with a turbulent period at Gallaudet. Kids with hearing loss, thanks in part to advances such as cochlear implants, have been increasingly mainstreamed into hearing schools, a move that has hurt enrollment at deaf-only schools. At Gallaudet, academic standards for admission dropped as a result and administrators were pressuring professors to doctor grades for underprepared students, according to a 2006 investigation by the Washington Post. By 2007, with the graduation rate hovering around 40 percent, the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, the university’s accrediting body, put Gallaudet on probation.

With the academic troubles came political strife. In 2006, the year Hansel Bauman arrived, the student body erupted when the board appointed Jane Fernandes, the school’s provost, to serve as president. The students mostly complained that she was too strict a disciplinarian. But Fernandes, a deaf woman who had learned ASL as an adult, accused them of thinking she was “not deaf enough.” After protests shut down the campus for days, her appointment was withdrawn, angering the trustees who had selected her. The board chair resigned, as did board member Senator John McCain.

Throughout the uproar, work continued on the Sorenson Center. The building incorporates ideas from the faculty’s initial meetings and from the Baumans’ and Bahan’s class—doors that whisk open as students approach, furniture that promotes face-to-face discussion, and hallways that allow passers-by to see one another from long distances.

When it opened in 2008, the structure instantly shifted expectations about buildings on campus. “Everyone started asking questions,” Hansel Bauman says. “ ‘My gosh, if this is true for this one building, then the rest of the campus. . . .’ They really started seeing the possibilities.”

The fact that DeafSpace felt so revolutionary in the early 21st century may come as a surprise.

In the 1890s, Olof Hanson, an alumnus thought to be the nation’s first deaf architect, designed a dormitory at Gallaudet that anticipated and inspired the DeafSpace team’s findings—chiefly by maximizing natural light.

In those days, though, the emphasis wasn’t on bending the built environment to the needs of deaf students. Hanson’s bigger legacy was his activism against discrimination, most famously convincing President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 to reverse federal policy that excluded the deaf from employment in the civil service.

That tension—between making the world conform to deaf people’s differences and forcing them to adapt to the world—has long roots at the school. Founded by Edward Miner Gallaudet in 1864 on a charter signed by Abraham Lincoln, the university was named for Edward’s father, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, who had started the American School for the Deaf in West Hartford, Connecticut, 50 years before. The elder Gallaudet had helped codify American Sign Language, which then flourished across the country.

Edward Gallaudet was a staunch defender of ASL, but even at his school, for much of the following century, it was often undervalued. Amid a sharp debate among proponents of “manualism” and “oralism,” deaf children were taught to lip-read and speak English. As late as the 1950s, some professors at Gallaudet viewed their students’ signing as a sort of crude pantomime.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that William Stokoe, a Gallaudet English professor and pioneering deaf linguist, demonstrated that ASL was a full-fledged language with its own grammar and dialects. It has also been a great source of pride among the deaf—many of whom prefer to call themselves Deaf, with a capital D. Like any linguistic group, they consider ASL a key to their social identity. In 1988, the deaf-identity movement spurred the Deaf President Now campaign, which resulted that year in the hiring of Gallaudet’s first deaf president, I. King Jordan. The campaign not only galvanized the national deaf community, but it alerted many in Washington to deaf-rights issues and led to the passage of legislation on behalf of deaf access, including the requirement that TVs be equipped with closed captioning.

The Sorenson Center became the first physical space built around that modern ethos of self-determination.

Hansel Bauman left California to take up his post at Gallaudet in 2009.

The next year, the university invited firms to compete to design a new dorm, Living and Learning Residence Hall 6, now known as LLRH6. The school settled on a design/build team helmed by New York’s LTL Architects, a boutique firm known for a striking contemporary-art gallery in Austin, Texas.

Finished in 2012, LLRH6 shows the deepening sophistication of the DeafSpace approach. An ingeniously slanted great room on the ground floor, which can morph from a student lounge into an auditorium, follows the natural slope of its site to the north of Gallaudet Mall, the school’s main quad. A gentle downward ramp allows for easy signing while walking—unlike stairs, which you have to keep an eye on. The furniture is configured to fit groups of all sizes, for talking or studying, and the ramp accommodates people who use wheelchairs and canes. (The next frontier of DeafSpace, Bauman says, is design for the deaf-blind.)

The university is also renovating its science labs along DeafSpace principles. Before designing them, Bauman’s team set up a design “incubator” in a vacant warehouse, where they tracked the movements of students and faculty with GoPro cameras to see how they interacted in a lab setting. Differently, it turned out, than researchers expected: Instructors tended to walk behind students, not stand at one end of the table. They also found that lab benches and ventilation hoods obstructed sightlines as they were originally configured.

This year, Gallaudet broke ground on another new dorm for the small high school on its campus, the Model Secondary School for the Deaf. Designed by Dangermond Keane Architecture—a small Portland, Oregon, studio—in collaboration with Baltimore’s Gaudreau architecture firm, it will represent the state of DeafSpace design theory when it opens next fall.

Even as the logic of DeafSpace was shaping the campus over the past decade, a different force has reshaped the surrounding neighborhoods of Trinidad, Near Northeast, and Ivy City: Once crime-ridden and largely poor, the school’s neighbors have become caught up in the District’s real-estate boom.

The original Olmsted and Vaux campus, designed as a refuge from the city, seems especially anachronistic now that Gallaudet finds itself anchoring an ever trendier part of town. Just across Sixth Street, Northeast, is Union Market, the artisanal-food mecca, and a bit farther southwest are the luxury apartment towers of NoMa. H Street’s nightlife is several blocks to the south. All of this presents the school with a financial opportunity in the big parking lots it owns on either side of Union Market. The administration’s answer is to welcome the city in, largely through a big new front door.

In partnership with the developer JBG Companies, Gallaudet recently applied for a million-plus-square-foot development spanning both sides of Sixth Street. With a planned 1,800 apartments, offices, stores, and a “makerspace,” the cluster of new buildings will effectively form a new city district—and a deaf-friendly one. “Green fingers” of lawn and plantings, studded with round seating areas and glare-free lighting, will link the campus to the Union Market area. The centerpiece will likely be an eye-catching small building in a new “gateway plaza” at Sixth and Florida.

The master plan is being devised by New York architect Morris Adjmi, who designed the Atlantic Plumbing building at Eighth and V streets, Northwest. “The idea is really to take down the physical barriers [between Gallaudet and the city] but also to expand the footprint of the school metaphorically,” says Adjmi, who has met with students, faculty, and neighborhood groups during the early planning phase.

Moving the DeafSpace concept across Sixth Street will be “a handing of the baton,” says Bauman, “a way to get what we’ve done on campus out into the public. We have modest hopes of influencing how everybody thinks, not only about Sixth Street but generally about urban development.”

It may change how we think about designing for different kinds of bodies, too. The requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act tend to exasperate architects, but Bauman points to the example of the sidewalk curb cut and “how easy that makes life for everybody”—people pushing strollers or riding bicycles as well as wheelchair users.

In September, a large crowd gathered in the I. King Jordan Student Academic Center to hear Bauman announce the competition for the Sixth Street Revitalization.

He talked about how it would redefine the way Gallaudet related to the city and the world. But it was Fred Weiner, the university’s assistant vice president for administration, who described the mechanism by which the relationship could change, and who offered some history.

Weiner compared the future of Northeast DC to the past of Martha’s Vineyard. In the 19th century, the town of Chilmark on the Massachusetts island had an unusually high rate of hereditary deafness, about one in 25 people. Local sign language—a precursor of ASL—became an unofficial second language in the town, a means of communication used by almost everyone, deaf or hearing.

Weiner believes something similar can happen on Sixth Street. Today it’s common to see servers at Union Market’s TaKorean or Rappahannock Oyster Bar signing to customers. That integration, Weiner says, can only benefit new residents arriving daily in the neighborhood: “When deaf and hearing people interact on a regular basis, a transformation takes shape.” Even neighbors who don’t learn how to sign, he predicts, will be more aware of how to communicate through gesture and technology—using mobile devices, for example.

That seemingly modest start belies its potential for design of all kinds. Dirksen Bauman likes to talk about “deaf gain,” a sort of theoretical opposite of “hearing loss.” Deaf people, he and a coauthor argued in a 2014 Psychology Today article, “have the potential to provide insights into the wider practices of say, architecture, filmmaking, video game design, bilingual education.”

The new neighborhood taking shape at Gallaudet may, in the years to come, recast not only Northeast DC but our understanding of how all bodies inhabit the space around us.

Amanda Kolson Hurley has written for the Atlantic and the American Scholar, among other publications. She lives in Silver Spring.

This article appears in our January 2016 issue of Washingtonian.