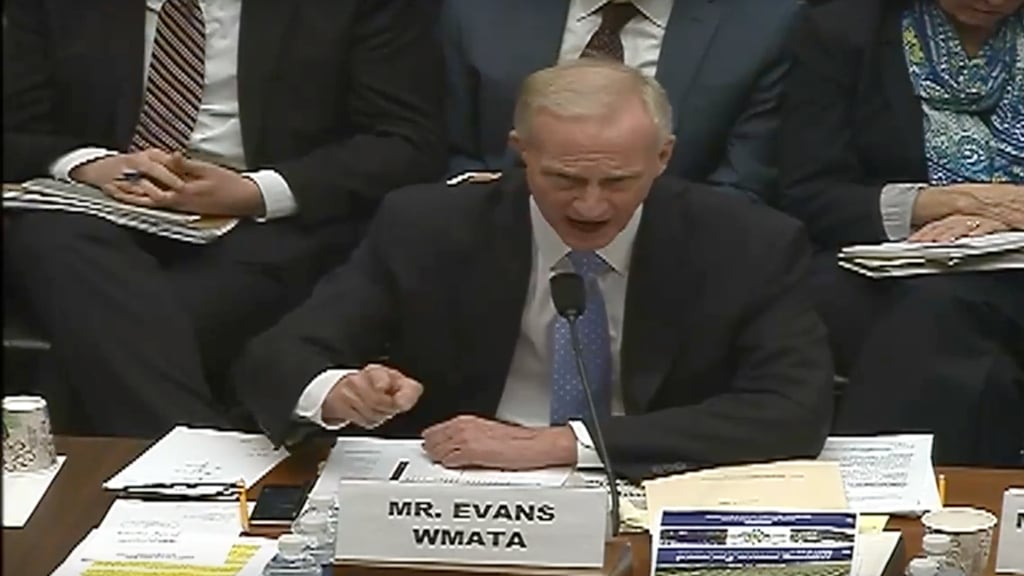

It didn’t take long for a congressional hearing into Metro’s condition to devolve into a screaming match. All Jack Evans, the chairman of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, had to do was ask for money. In his opening remarks, Evans asked a joint hearing of the House Oversight subcommittees on government operations and transportation for the federal government to pay the same amount that the geographic jurisdictions served by Metro do each fiscal year.

“The federal government, an equal partner in governing the system with four board members, should contribute $300 million per year to the operating budget just like DC, Maryland, and Virginia,” Evans said.

Representative John Mica, a Florida Republican who chairs the government operations subcommittee, responded by barking at Evans about the District’s municipal budget, which currently has reserve funds of $2.1 billion. (Evans is also the longtime DC Council member from Ward 2.)

“I am not going to support bailing out the District of Columbia,” Mica said. “Virginia needs to step up to the plate, Maryland needs to step up to the plate, and DC with that huge surplus needs to step up to the plate!”

Evans attempted to clarify that DC’s city budget is separate from Metro’s budget, but Mica, like many of the representatives from districts beyond the region, seemed more interested in nabbing a good anti-Washington sound bite than fixing a problem. Mica also seemed to shrug off Metro General Manager Paul Wiedefeld‘s updates about the emergency repairs made during last month’s sudden one-day shutdown and future maintenance plans in favor of demanding he fire people. Rather than splitting along party lines, the Metro hearing was divided between the representatives whose constituents ride Metro and those whose constituents do not.

Wiedefeld, for his part, tried to explain that much of Metro’s unspent funds are actually allocated toward established projects, such as the purchase of 748 new 7000-series cars to replace the oldest, least-safe cars in Metro’s aging fleet.

“Does Mr. Mica know know the difference between obligated funds and expended funds?” asked Virginia Democrat Gerry Connolly.

“No,” Evans chimed in.

“I wish you well,” Mica told Wiedefeld. “We’ll work with you. You have the money. You need to fire people to get that place in order.”

But Representative Mark Meadows, the North Carolina Republican who runs the transportation subcommittee, proceeded to conjure hypothetical situations in which Wiedefeld himself would be on the firing line, prodding Evans to describe a situation in which he, as Metro’s chairman, would find a reason to dismiss Wiedefeld, who just took over last November. Evans tried not to entertain Meadows’s scenarios.

“Paul is in charge,” Evans said.

But that was after Evans and Meadows got into it over Evans’s request for more money from the federal government. Evans said that over the next decade, the system needs about $18 billion for operations and needed repairs, a figure that made Meadows balk.

“Your plan to fix this system is to give WMATA $18 billion and close it down for six months?” he said, referring to Evans’s since-retracted statement that the Blue Line could be forced to shut down for an extended period.

Evans squirmed away from his original quote, but said his goal is to make Metro a “world-class” urban rail system on par with those in Beijing, Shanghai, Moscow, London, and Paris. Then things turned theatrical.

“Those are all communist countries!” screamed Meadows, who was born at a US Army hospital in Verdun, France.

“London? Paris?” Evans responded.

“Beijing! Shanghai! Moscow!” Meadows yelled back, apparently unaware of the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991.

That just made Evans more incredulous. While Congress has contributed $150 million per year for Metro’s capital expenses, it does not spend anything on Metro’s operations, even though—as Evans pointed out several times—50 percent of the DC-area’s federal workforce rides uses it to commute.

“You want this to be safe?” Evans yelled. “You want this to be reliable? Or do you just want to leave here and do nothing? Next time something happens, I’m blaming you guys!”

For their part, Connolly and the other members of the Washington-area delegation—Republican Barbara Comstock and Democrats Don Beyer, John Delaney, and Eleanor Holmes Norton—were not exactly gentle with Evans and Wiedefeld, but they were more realistic than their further-flung colleagues. Connolly and Comstock both expressed their desires to see some heads roll, though not Wiedefeld’s. If there are people who need to be fired, it’s the employees who have become either negligent or redundant. Comstock called out findings that Metro’s maintenance crews often work without standard repair kits.

“Let’s focus on our new general manager, who has set out some really good ideas,” Comstock said. “There’ll be time for the food fight later.”

And when Evans repeated his frequent call for Metro to have a dedicated funding source like a regional sales tax Norton called him out on using it more as a slogan than a solution. “This notion of a dedicated funding source has become a mantra,” she said. “Put something on the table.”

Evans said eventually he doesn’t have anything plotted out, and that the only model he’s ever examined is a special tax district the federal government established in the 1930s in states served by the Tennessee Valley Authority. The admission was another reminder that a dedicated funding stream might not be the surefire solution Evans touts it as.

“I think it’s not a simple answer,” Zachary M. Schrag, the author of The Great Society Subway, a history of Metro, told Washingtonian in a recent interview.

While Evans sparred with Mica and Meadows over finances, Wiedefeld’s role seemed to be to explain to the members of Congress that fixing Metro will take more than overnight wishes and one angry afternoon on Capitol Hill. On March 31, Wiedefeld wrote in a public note that will release a “long-range maintenance plan” within six weeks.

Meadows called for another hearing in 90 days before any big decisions are made.