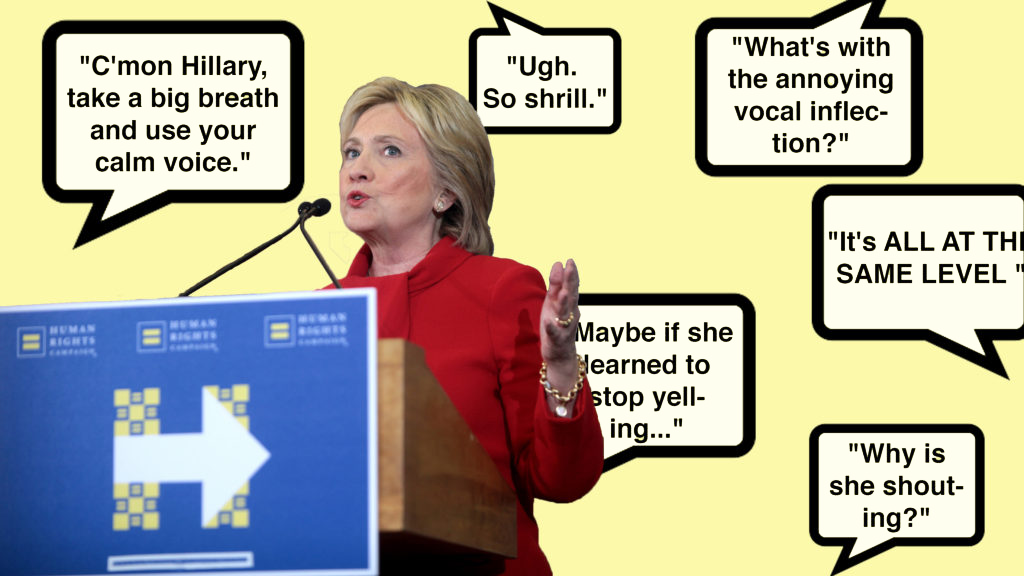

The balloons hadn’t even begun to drop after Hillary Clinton’s speech at the Democratic National Convention this summer when pundits started scoring the way she sounded. There was Brit Hume of Fox News complaining about Clinton’s “not-so-attractive voice” and saying, “She tends to accelerate her delivery and speak louder and sterner.” There was New York Times columnist David Brooks demanding more “humanity” from the country’s first female presidential nominee: “She projects one emotional tone throughout, and it has a combative manner to it, and not a happy warrior manner.” Donald Trump himself took to Twitter to chastise Clinton’s “very average scream.”

None of this would have come as a surprise to any woman who’s run for office. The same way a female politician’s clothing and appearance get picked apart before her policy proposals do, so do the tone and timbre of her voice—something you rarely hear about male pols, stentorian and not so stentorian alike.

As I opined on TheFive today- a "check the box" speech. Immigration, income inequality, more. Btw what's with the annoying vocal inflection?

— 🇺🇸 ERIC BOLLING 🇺🇸 (@ericbolling) July 29, 2016

C'mon Hillary, take a big breath and use your calm voice. You can do it.

— Rick Sanchez (@RickSanchezTV) July 29, 2016

Since she entered the national spotlight, Clinton in particular has barely been able to open her mouth without people disparaging the sounds that come out of it. Marc Rudov set the tone of the 2008 Democratic primary when he told a Fox News panel, “When Hillary Clinton speaks, men hear ‘Take out the garbage.’ ” Clinton “shouts,” the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward said earlier this year. She gives “angry, bitter, screaming” speeches (Sean Hannity) and tends to “shriek” (Geraldo Rivera).

How do Clinton and other female politicians defend against this, our culture’s inbred animosity toward women who seek positions of power? By turning to a little-known cottage industry within the dark arts of political image-making that’s dedicated to teaching women politicians how to speak in public.

In particular, Washington vocal trainers such as Chris Jahnke.

Jahnke, who speaks with the vital warmth of a particularly charismatic librarian, often works out of a small windowless training room on K Street. The setting belies her prestige: She was a consultant on Clinton’s 2008 campaign and has prepped Michelle Obama.

Jahnke didn’t set out for a career in politics. She grew up in Albert Lea, Minnesota, in a family, as she puts it, of “people who worked on their feet all day”—namely, farmers and laborers. She wanted to become a television reporter and landed her first job right out of college, as the weekend weathercaster at a station in Rochester, Minnesota. Unexpectedly, she hated it. “I was nervous, extremely nervous,” she recalls. “The whole experience was truly humbling.”

Jahnke moved up from reporter to anchor but never overcame her stage fright. “I quickly learned that I wanted to be the person behind the camera, making things happen for other people,” she says. She quit TV and went to work for Michael Dukakis’s 1988 presidential campaign. During the vice-presidential debate between Lloyd Bentsen and Dan Quayle, when Bentsen threw out his now-infamous dig, “Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy,” Jahnke says she was starstruck. She wanted in on the stagecraft that goes into creating that kind of moment—but working for female candidates: “I knew that there was a perspective that I could bring to women that other consultants just couldn’t.”

It turns out Jahnke was right. Most politicians today do some kind of media training, whatever their gender, but for women it’s crucial. A few years ago, researchers at the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, an organization in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that studies women running for executive office, began research on what makes female candidates succeed and discovered voice was a crucial factor. Again and again in focus groups, voters described feeling agitated by the sound of women giving political speeches. “People were quite sensitive to women officeholders sounding shrill, loud, or boring,” says Adrienne Kimmell, the foundation’s executive director.

The finding echoes years of studies showing that we don’t like the way women talk. People associate low voices—which is to say the ones generally innate to men—with competence, leadership ability, and intelligence. In one study, a professor at the University of Miami played a short stump speech in a variety of vocal pitches and found that people were more likely to vote for candidates, both men and women, with lower voices. The same researcher looked at the 2012 House election and found that those who won their races tended to have lower-pitched voices than their opponents.

This bias against talking-while-female is almost a double blow today. As it was in the age of FDR’s fireside chats, the inspirational address is still the gold standard voters use to judge politicians. Yet our 24-hour media cycle means women candidates are under infinitely more pressure to come across as likable—and are subject to more scrutiny when they don’t. Men “can get up there and scream their hearts out,” says Stephanie Cutter, a political strategist who was President Obama’s deputy campaign manager in 2012. “A woman gets up there and does the same thing and she’s characterized differently.”

For Jahnke, the career change from TV personality to TV coach was perfectly timed. After a few years assisting Michael Sheehan, a DC media trainer who has worked with Bill Clinton and John Kerry, Jahnke struck out on her own in 1991, just in time for what the press would later call the Year of the Woman. A record number of female candidates were elected to national office that year, including four to the Senate. One of them, Patty Murray, now the senior senator from Washington state, was in that first wave of Jahnke’s clients.

“Even now, I rarely meet women candidates who have decided early on that politics is a career path,” Jahnke says. “Rather, they get into it because of something that happened to their family or because they want to make a difference.” (Murray, who decided to run after a state official told her he wasn’t interested in the opinion of a “mom in tennis shoes,” is Jahnke’s classic example.) As such, “they can recite policy forwards and backwards, but they’re not necessarily good on camera.”

In the early years, Jahnke spent much of her time convincing these women it was worth it to learn to speak for the camera. Now “they get it,” she says. “It’s just part of the job.”

***

Jahnke signs confidentiality agreements with most of her clients (what woman seeking to come across as authentic and likable wants to cop to the coaching it takes to get there?), so she can’t disclose what it was like to train any of them. But she agreed to train me.

Before our appointment, she asks me to fill out a form. I list a few of my favorite speakers: novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, journalist Hanna Rosin, Sheryl Sandberg. Later when we meet, Jahnke laughs at my selections. “Usually no one lists any women,” she explains.

“Even women?” I ask.

“Even women.”

A stint with Jahnke can comprise a lone day of work or months of consulting on a campaign, during which she’ll travel to a candidate’s home state to observe her at events. “You can pay a little or you can pay a lot, but you tend to get what you pay for,” she says, declining to disclose her fees. (Jahnke isn’t just a hired gun—she has politics of her own. For instance, she trains only pro-choice Democrats.)

My role-play takes place in her DC training room, filled with a dozen child-size school desks. Jahnke sets up a video camera to record me giving a story pitch to an editor (because I don’t give stump speeches). I’m positioned at a podium, in front of a poster of a billowing American flag. According to Jahnke, I’m “pretty good.” (Phew.) My voice is deep enough to be commanding without extra work.

But! I could also improve.

Most of my problems involve basic public-speaking skills: not making eye contact with my audience, not stopping to breathe at the end of a thought, not varying my tone and pitch to correspond to the intensity of what I’m saying. Which makes sense—there’s a reason I’ve chosen a line of work where I spend more time at a computer than addressing crowds.

Some of the issues are gender-related, such as the way I stand. “Notice what you did there,” Jahnke says, pointing toward the screen. I stare at my face but can’t see what she’s talking about. She indicates my hands, which I suddenly notice are gripping the podium as if I’m trying to keep myself from falling down. “See how that collapses your shoulders,” she explains. I look again—she’s right. I appear to be shrinking from the room.

Body language is something an elite trainer of Jahnke’s caliber can easily teach. Less straightforward are the biological differences intrinsic to men and women. Women tend to have shorter vocal cords. When we speak, our cords flutter, and the shorter ones produce faster vibrations, which in turn can build a higher—often breathier—pitch. A trainer can lower a person’s pitch, but only to a degree.

“I can’t change [a female client’s] physiological pitch, but I can teach her to relax her throat and use breath support,” says Susan Miller, another Washington vocal trainer. “It’s like making sound through a piccolo versus an alto sax—just breathing right will move the tone lower and make the pitch more resonant.”

But blindly lowering a woman’s voice without taking into account other factors can backfire. “If we use a lower pitch and are louder, we’re perceived as more aggressive,” Miller says. Thus, many trainers take a holistic approach, focusing on a client’s overall speaking pattern.

Jahnke teaches multiple skills that serve different purposes: a low pitch and slow rate of speech for moments when you want to be calm and composed; a high pitch, used sporadically, to show “excitement and enthusiasm.”

“I can show you endless clips of men being . . . grrr,” Jahnke says as she pulls her face into a grimace and wags her finger. “They just look authoritative. A woman does that and she is shrill, angry.”

Remember during the Republican primaries when Donald Trump questioned whether anyone would vote for someone with Carly Fiorina’s face? At the GOP debate that followed his comment, Fiorina was asked to respond. According to Jahnke, her delivery was textbook.

“She’s calm; she’s acutely aware of the split screen,” Jahnke says. “Notice how slowly she spoke—if she’s angry, she might speak more quickly and her pitch will rise. So she’s very in control of her speaking tone. Donald can do whatever he wants, but she has to not show emotion. Because the moment she becomes wild or angry, she loses.” (Frank Sadler, Fiorina’s campaign manager, tells me she didn’t train herself during the race, though as a former CEO of Hewlett Packard, she might have received prior training. “Working in tech, she’s dealt with men like that her whole life,” Sadler says.)

Very few women in power can appear angry without facing criticism—Elizabeth Warren is an exception, according to Jahnke. The senator’s “steeliness comes through in a way that’s not overdone,” she says. But for almost every other female politician, the only way to respond to criticism is with competence or humor. To demonstrate, Jahnke plays a clip of Hillary Clinton during a 2007 debate. At one point, moderator Tim Russert baits Clinton by asking her to answer a scenario about torture. When she criticizes it, Russert reveals that the scenario was originally proposed by her husband.

Instead of getting angry, Clinton’s lips pan out into a smile. “I’ll have to talk to him at home,” she says. The audience laughs. Clinton wins the point.

Jahnke teaches a similarly stealth move for interrupting men. If a woman just butts in—my technique when I find myself drowned out in editorial meetings—she comes across as hostile. The trick, says Jahnke, is to wait for the speaker to take a breath. In that pause, she says, you break in with two things: the person’s name (people stop when they hear their name) and a leading phrase (“That’s a great idea, Joe, but we need to consider . . . .”). The idea, Jahnke explains, is to make your voice heard without allowing a man to feel that his idea is being dismissed or demeaned.

And you have to smile. She demonstrates for me: “I’ve just looked at him, I give him a little gesture, I’ve got a wide smile on my face, and I totally cut him off.”

***

I talked to all kinds of women professionals who have used Jahnke’s or another vocal trainer’s services—an ob-gyn preparing to testify about abortions before Congress, a prosecutor serving as a commentator on civil-rights issues, several climate scientists, journalists. Most regard the mastery of their craft as a necessary evil.

“I hate feeling that I’m pandering to a fundamentally sexist perception,” says Anna Day, a freelance broadcast journalist who specializes in reporting from conflict zones. “But at this point, when I’m trying to convey stories about which I’m passionate, I don’t want to take away from that.” So she lowers her voice a couple of octaves.

Sally Kohn, a CNN political commentator, says that before every TV appearance, she deliberates about how she wants to sound: “The choice I make personally changes from day to day depending on my mood. Some days, it’s more of an F-that. You don’t want to be like, ‘Yay, women, please conform yourselves to a misogynistic, sexist expectation.’ ” Other days, not so much. “You gotta know the game you’re playing.”

Christine Quinn, a former speaker of the New York City Council and a current commentator for CNN, refuses to change her projection at all—despite having been heavily criticized for her voice during her unsuccessful 2013 mayoral run. Image-shifting “can be debilitating,” Quinn says, especially during a campaign “when you want your ends firing at the same time.”

Longtime GOP consultant Mary Matalin agrees: “You can see that with Hillary. You can obviously see what she’s doing. Slowing down, lowering her voice. And I think, to some extent, at the expense of her message.”

Ah, Hillary. In the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher worked with a theater coach named Kate Fleming to move from the light, feminine timbre she had employed while running for Parliament to the tone that established her as the Iron Lady—and led to her record as the longest-serving prime minister of Britain in the 20th century, not to mention the first woman to hold the office. By some suspicions, Clinton has put in similar work to go from the soft- and sweet-spoken Arkansas governor’s wife to low-voiced ladyboss in the Senate and State Department. Yet in the eyes of the internet’s peanut gallery, she still hasn’t managed to contort her voice into the infinitesimally small Venn intersection between “competent enough to lead” and “likable and inspiring.”

It’s frustrating—that we have to play-act, that it takes rehearsing to come across as the “authoritative but approachable” woman. Then again, the interrupting trick I learned from Jahnke has been life-changing—perhaps the most practical career advice I’ve ever received. It’s become the story I tell over brunch, and more than once, women from other tables have overheard and asked for a demonstration. When I put it to use myself, people around me shut up and my words come out with force. I guess this is what it’s like to be one of the men in the room.

This article appears in our September 2016 issue of Washingtonian.