Shortly after the Hirshhorn announced its Yayoi Kusama retrospective last year, the Washington Post told its readers that if they took a selfie in one of the Japanese artist’s kaleidoscopic mirror rooms, they were “part of the problem.”

“I should be thrilled,” the author of the piece, Lavanya Ramanathan, said of the announcement. “Instead, I’m bracing for the possibility that I may never make it up the museum’s narrow single-file escalators to see it, all because Kusama is an Instagram darling.”

Ramanathan’s argument—that Instagram-obsessed crowds are ruining the museum experience for the true art-lovers—has become an increasingly common refrain among critics as more and more museums embrace experiential, immersive exhibits. DC saw its fair share of them in the past few years: “The Beach” and “Icebergs” at The National Building Museum, “SONG1″ at the Hirshhorn, and of course, “Wonder” at the Renwick Gallery, which inspired a wave of think-pieces on whether social media-friendly exhibits are “good for art.”

Meanwhile, these “Instagrammable” exhibits are attracting the most diverse group of people that the traditional art world has ever seen, bringing people into museums who might otherwise not set foot inside them. They’re also breathing new life into the museums, themselves. During its eight-month run, “Wonder” brought in about 732,000 viewers. Annual attendance before “Wonder” was about 150,000. “Something I never thought I’d see in my lifetime was a line around the block to get into an art museum,” says Nicholas Bell, the curator behind “Wonder.” The bump in attendance also means more people are likely return to the museums for less splashy shows.

According to critics like Ramanathan, however, the newcomers in those lines are “interlopers” and “exhibit hogs.” She theorizes they’re only going to the Kusama exhibit to take pictures of themselves, a claim that was also made during “Wonder.” In her piece, “The Renwick is suddenly Instagram famous. But what about the art?” the Post’s Maura Judkis writes, “Yes, they’re coming to see the art — but more important, they are coming to photograph, and be photographed with, the art. Sometimes it’s hard to tell which they care about more.”

Ramanathan’s piece does not include reporting that asks people why they’re visiting the exhibits. But even if the crowds do include people who are just in it for the Instagram likes, why does that matter?

“Any time you make something more inclusive there will always be people who feel that something is lost,” says Lisa Strong, a professor of museum studies at Georgetown University. But whatever individual museumgoers are losing to the rise of participatory exhibits (namely, empty, quiet spaces where they can stare at art) becomes trivial when you consider their benefits.

Despite the success of “Wonder,” Bell says he had to constantly defend its social-media friendliness. He was bombarded with questions like, “But wouldn’t it be a better experience if people weren’t using their phones?” In response, Bell said that he avoided rendering a judgement—good or bad—on the thousands of visitors who chose to share a photo of their experience on Instagram. Instead, he positioned the museum as a “non-partisan platform for engagement.” He asks, “Why would we act as the moral arbiter as what is an appropriate or inappropriate experience in the museum?”

This gets to another common argument against using social media in art exhibits: If you’re looking at art through your phone, you won’t have as fulfilling and meaningful of an experience. Some critics cite a 2013 study that found that people who take photos of art don’t connect with it as deeply and are less likely to remember it later. But as Strong points out, this study wasn’t conducted in experiential exhibits like “Infinity Mirrors,” so you can’t apply its findings across all artworks.

“People experience art in much different ways,” Strong says. “Some people have a much better experience and understanding of art if they can participate with it as opposed to just looking at it.”

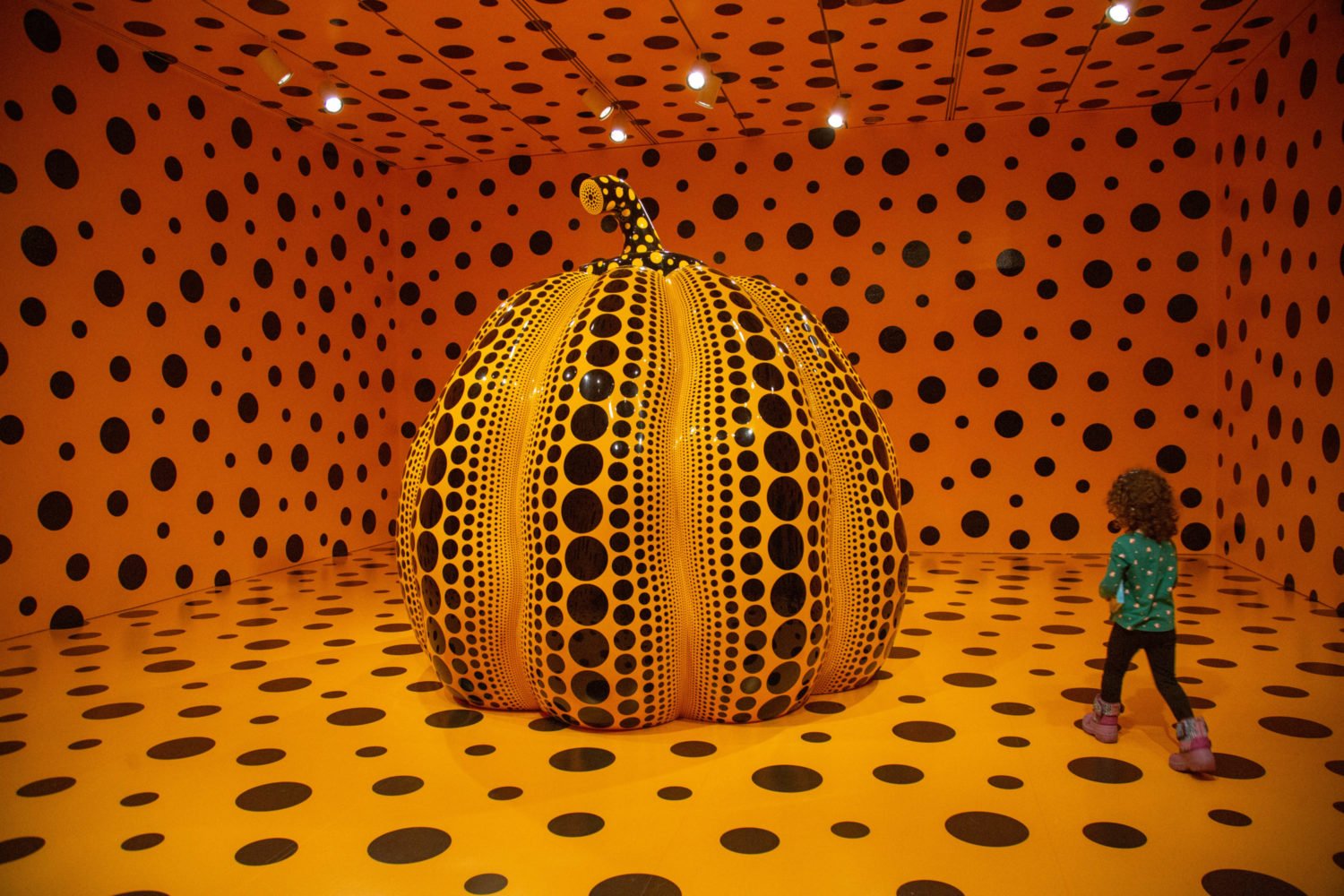

In the context of the Hirshhorn’s Kusama exhibit, the fact that people are sharing their experiences on social media is arguably part of the artist’s intention. Beginning in the 1960s, Kusama staged interactive and performative art exhibits that were ready-made media spectacles. She painted naked participants in colorful polka dots in public and made sure major newspapers knew about it. “Polka dots symbolize disease,” Kusama said in a 1999 interview with BOMB magazine. Like disease, she saw polka dots as spreading and enveloping everything in their path.

And with her infinity mirror rooms, she wanted to create an experience of “self-obliteration” through the infinite repetition of your image reflected back at you. As Priscilla Frank argued in the Huffington Post, “The notion of Internet virality, then, logically follows, with images of polka-dotted selfies spreading like polka dots themselves over the infinite expanse of the internet.” So if you choose to take a selfie in one of the immersive, cosmic mirror rooms and share it on social media, think of it as a way you’re participating in Kusama’s idea of the infinity.

While critics will continue to engage in the somewhat pointless argument of whether social media-friendly exhibits are good for the art, itself, these exhibits will only become more common.

As Bell says, “Everybody has a camera in their pocket, and they’re going to use them, and life will be simpler if you embrace it.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Maura Judkis’ piece did not include reporting asking people why they visited “Wonder.”