About DC Music issue 2022

Check out our entire DC Music issue here, including 20 classic albums, 5 intriguing new artists, and a huge list of local venues.

There’s something eerie about a nightclub in the daytime. Minus the crowds, the lights, the noise, everything seems a little too bright and a lot too quiet—less like a concert venue than some creaky old library. That was certainly the case at the 9:30 Club one recent afternoon. But the odd vibe also felt right. Because I wasn’t there to hear some band: I wanted to dig into the past.

The 9:30 Club has occupied this space at Ninth and V, Northwest, since 1996, and it needs no introduction to music fans—it’s among the country’s best-known and most-loved places to see live music. It has hosted thousands of local and national artists, from music pioneers (Bob Dylan, James Brown, Johnny Cash) to alt-rock favorites (Smashing Pumpkins, Radiohead, Foo Fighters) to hip-hop and pop stars (Drake, A Tribe Called Quest, Adele). If you live in the DC area and care about music, you’ve likely spent time inside 815 V Street.

But have you ever wondered about the building itself? Most visitors probably aren’t aware of its long history, stretching back to its days as a nightclub in the 1940s. As I walked around the empty room with Seth Hurwitz—who owns the club, as well as the Anthem and other local venues—it was easy to envision the early years, when Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington might have had the place hopping. I remembered going to one or two hardcore shows there in the 1980s, a time when the hall seemed semi-abandoned and a little dangerous. Yet I wanted to know more about the story of this local fixture. So I decided to go back to the beginning and see what I could find out.

One place where you might begin is with a letter from President Harry Truman. On October 12, 1945, Truman wrote to Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., whose wife, the pianist Hazel Scott, had just been barred from performing at the DAR’s Constitution Hall because she was Black. Truman was unhappy about the situation, yet there was no way he could interfere with the workings of a private organization, he wrote.

This state of affairs didn’t sit well with a local nightclub owner named David Rosenberg. “Everybody talks about [the barring of] Hazel Scott from the DAR hall, but nobody does anything about it,” he told the Washington Afro-American newspaper six weeks after Truman’s letter. Well, he was going to do something about it. Rosenberg had previously owned Club Bali on 14th Street. He also operated a restaurant, the Spot, at Ninth and V. Now Rosenberg was going to build a major new music hall on the former site of the Spot, and he intended to make it one of Washington’s earliest integrated music venues, welcoming performers and audiences regardless of their race.

The project was a big undertaking: a large-scale hall that would hold 3,000 people. To design it, he hired the prominent African American architect Albert I. Cassell, who had previously served as the official architect of nearby Howard University. Rosenberg promised that while his place would be smaller than Harlem’s famed Savoy Ballroom, it would be “much nicer.”

When it opened on January 12, 1947, the Music Hall, as it was called, offered a weeklong stint by Louis Armstrong. One newspaper account at the time marveled at the room’s RCA sound system and “scientifically designed fluorescent lighting.” Armstrong’s debut was apparently a hit: The Evening Star’s After Dark column recounted reports of “near riots” due to several thousand hopefuls who were shut out of the sold-out show. The Music Hall’s manager, identified only as Goldie, attributed the commotion to its being “the only modern dance hall in town.”

In the months that followed, the venue hosted the likes of Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie, Cab Calloway, and Ella Fitzgerald (singing in Cootie Williams’s band). But despite its flashy debut, it was not a success. Rosenberg’s startup costs seem to have ballooned: In 1945, he predicted that the project’s price would be $70,000; by 1946, the Evening Star was estimating it at $125,000. When the Music Hall opened just months later, the investment had blown up to $200,000—more than $2.6 million today. Rosenberg tried to make the price tag a bragging point, mentioning it in advertising (“Washington’s new beautiful $200,000 concert hall & ballroom”). But apparently the numbers didn’t add up. By November 1947, the Music Hall had failed: A DC court declared Rosenberg bankrupt. Ads for a court-ordered auction soon appeared in the Evening Star. That fancy RCA sound system and all sorts of other items were available to anyone who brought cash.

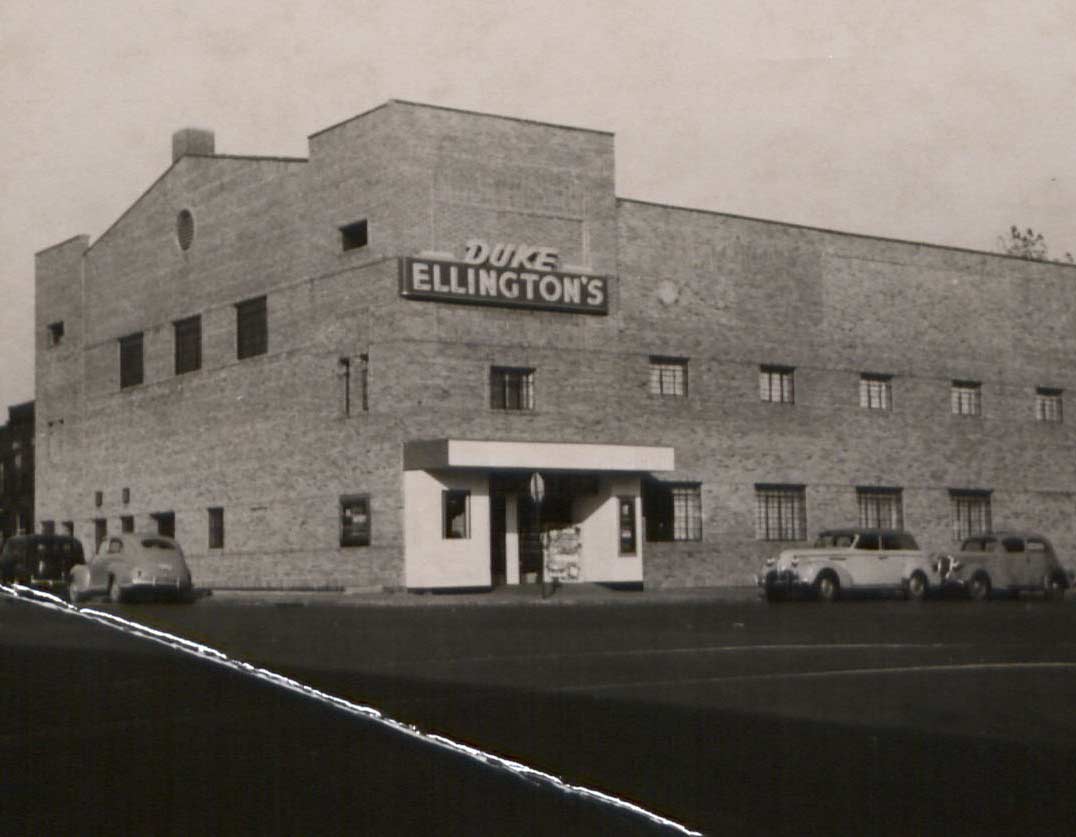

One person who must have watched the quick rise and fall of the Music Hall was Duke Ellington. The jazz superstar—who grew up in DC—had lived and hung out in the area, and he probably strolled past the corner of Ninth and V many times. With this fancy new venue now sitting empty, he and several partners saw an opportunity: They would open a jazz club of their own, called Duke Ellington’s.

The new owners renovated the space and invested in a big sign that no doubt turned heads on V Street. Duke Ellington’s opened on October 22, 1948, with a ten-day run by Ellington and his orchestra. This time, the scene was more muted—the first gig didn’t even sell out. Variety’s reviewer wondered if the $1.80 cover charge might be too high, while mentioning that the club didn’t have a revenue-generating liquor license. The sound system was also malfunctioning, making singer Kay Davis hard to hear. But that didn’t stop “jazz stomping couples” from packing the dance floor.

By May 1950, that glamorous “Duke Ellington’s” sign had been replaced by something more prosaic: “National Institute of Painting and Paperhanging.”

The business seems to have been in trouble from the start. Though big names like Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, and Buddy Rich were booked to perform, it was soon clear that Duke Ellington’s was struggling. In the November 6 edition of the Afro-American, columnist James L. Hicks sniffed that “the smart boys are saying the venture won’t last six months.”

The smart boys, whoever they were, turned out to be right. On December 1, less than six weeks after Duke Ellington’s opened, the Washington Post wrote that the place had shut down for “alterations” after failing to attract capacity crowds. The plan was to reopen on Christmas Eve with a different concept involving a floor show and chorus line. That revamp was short-lived: Duke Ellington’s was open on New Year’s Eve (it was one of 17 nightclubs cited for unsafe conditions involving blocked fire exits that night), but after that, it seems to have shuttered for good—a remarkably brief run. By May 1950, that glamorous DUKE ELLINGTON’S sign had been replaced by something more prosaic: NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PAINTING AND PAPERHANGING. Where Louis Armstrong only recently had the crowd jumping to “Hot Chestnuts,” now a trade school catered to aspiring wall-decorators.

That phase didn’t last long, though, and a dance school was operating there in 1954. The following year, it was occupied by the Caravan Ballroom, run by Bob McEwen. A well-known radio DJ, McEwen also produced and hosted the TV show Capital Caravan, which featured live R&B performances and teen dancers. The Caravan Ballroom became associated with DC’s mid-’50s mambo craze, thanks to the musician and dancer Roland Kave, who drew crowds on Saturdays. Admission was $1, but from 8 to 10 pm, the mambo lessons were free.

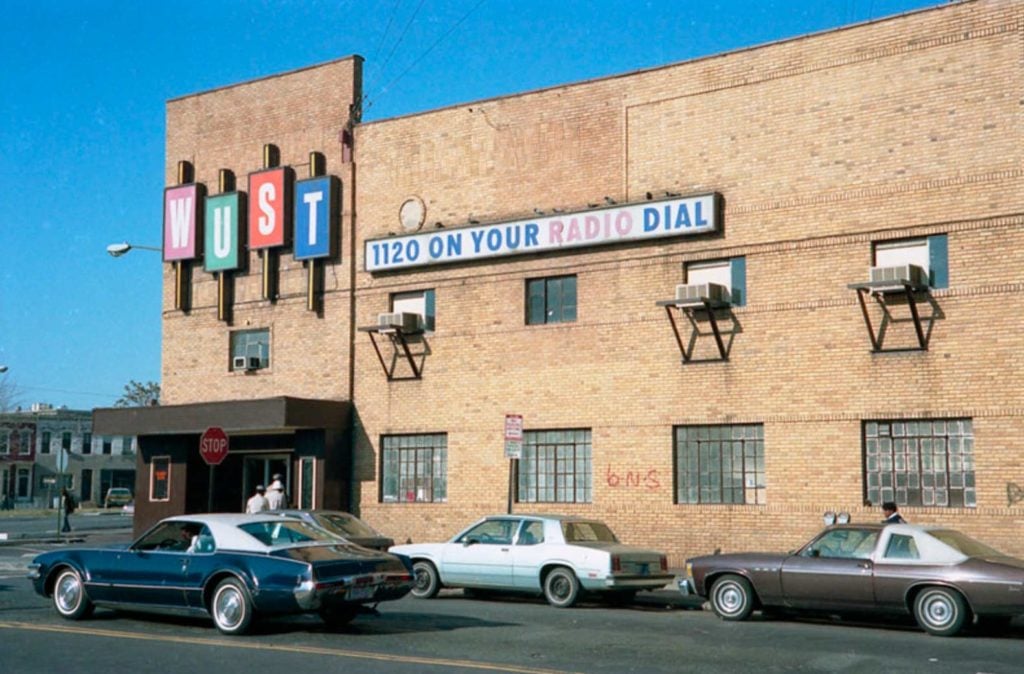

The next time you find yourself outside the 9:30 Club, look up. On top of the building, you’ll notice a skinny old radio tower poking skyward—the most visible relic of the building’s next iteration. In 1959, the radio station WUST moved in, having relocated from a studio on U Street (hence the call letters). Broadcasting at 1120 on the AM dial and playing primarily R&B, it was one of DC’s major Black-oriented stations at the time. Its most colorful star was Lord Fauntleroy Bandy, an African American DJ who delivered his on-air patter in a faux British accent.

The station was a vital voice of Black DC, serving a city that had become majority–African American in 1957. “WUST was down in the community interacting with the people, the working-class people in Washington, DC,” recalls Al Bell, a popular WUST DJ in 1964 and ’65 who later went on to fame as head of the legendary Memphis label Stax. “It was the era of entertaining disc jockeys. We interacted with our audience personally and knew who they were. We just moved into their lives.”

WUST was a daytime-only station, so at night the adjacent music venue was tapped for speakers, meetings, and other events. The Radio Music Hall, as it was known, became a crucial gathering spot for its community and a center of local civil-rights efforts. Malcolm X addressed a crowd there in 1963, and later that year the March on Washington used it as the home base for its volunteer corps.

“It had the soul—it had the thing,” says 9:30 Club owner Seth Hurwitz about the space on V Street. “As dumpy as it was, I swear, the minute I walked in, it was: We need to get this place.”

WUST’s programming attracted passionate fans. Al Bell had a particular interest in Southern R&B, and he started adding records by grittier artists like Otis Redding. But the station manager and co-owner, Dan Diener, told him to cut it out. “He said, you know, ‘Black people are more sophisticated in Washington, DC,’ ” Bell recalls. “ ‘The music you’re playing is not the kind they want to hear.’ ” The next day, Bell explained to his listeners what he’d been told, then gave out Diener’s phone number and encouraged them to share their thoughts. The response was so intense—listeners actually gathered outside WUST to show their support—that Diener called Bell into his office. Rather than chewing him out, he gave him a big raise.

In the early ’70s, WUST switched to an all-gospel format, playing records by the likes of Edwin Hawkins and the Swan Silvertones, as station fixture Cal Hackett explained to Billboard at the time. WUST also sold airtime to churches and individual programmers, including Harold Bell, whose “Inside Sports” was a DC staple. But in the ’80s, increased competition and a changing radio-business landscape eroded its audience.

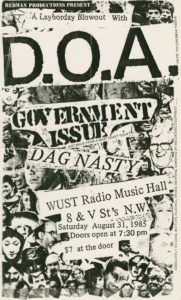

The building was still rented out for concerts and events, though, and go-go and punk bands started making use of the room: Chuck Brown, Dead Kennedys, Rare Essence. Dag Nasty playing its very first gig. A wild double bill of Bad Brains and Scream. The colorful WUST sign remained above the door, but many patrons were unaware what the letters even referred to.

WUST moved its operations out of the District in 1993, and the music hall was in increasingly rough shape—“ramshackle,” as the Post put it not long after the station departed. At that point, it seemed possible the old building wouldn’t be around much longer.

In the early ’90s, the 9:30 Club was a DC institution. Located on the ground floor of the Atlantic Building at 930 F Street, Northwest, the club had opened in 1980 and become one of the city’s most vital venues. But the room was famously cramped and grimy—packed with character but not exactly a comfortable place to see a show. When the Black Cat arrived on 14th Street in 1993, 9:30 started to seem a bit past its heyday. Then came the really bad news: The club’s landlord wanted to revamp the Atlantic Building and bring in fresh tenants. The 9:30 Club had to go.

So the venue’s then co-owners, Seth Hurwitz and Rich Heinecke, started to look for a new home. Their company, I.M.P. Presents, had previously rented WUST to put on some concerts, and Hurwitz and Heinecke decided to go take a closer look. “We walked into this place, and it was a relic,” Hurwitz recalls. Still, “I knew it was a cool place. It was just the vibe. It had the soul—it had the thing. As dumpy as it was, I swear, the minute I walked in, it was: We need to get this place.”

It took time to convince the family who owned the building to sell, but eventually Hurwitz and Heinecke were able to buy it. At that point, they faced another challenge: How do you turn a crumbling old room into an of-the-moment music venue? Hurwitz invited musicians he knew to come by and offer thoughts, including Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye, who suggested providing bands with a clean, comfortable backstage area rather than the kind of depressing digs that musicians more often encounter. So the new club would include amenities for weary road warriors like bunk beds in the dressing room and onsite laundry facilities. “The goal was to build a club that the bands would think was so great, they wouldn’t want to play anywhere else,” Hurwitz says.

The second 9:30 Club opened on January 5, 1996. David Rosenberg had died back in 1964, but if he was looking down from above that night, the scene probably seemed familiar: that same brick facade, another mob of fans angling for access to the city’s hottest new club, the familiar sense of anticipation hovering around the intersection of Ninth and V. Smashing Pumpkins performed, and while they weren’t exactly Louis Armstrong, they were one of the biggest rock groups in the world at the time. Just as in 1947, the opening night had the feeling of a major event—even if, as Post critic Mark Jenkins noted in his review, “the club proved more interesting than the band.”

And then . . . whoosh: sold-out shows, artists clamoring for a booking, the electric buzz that comes from being the place to be. Unlike the Music Hall and Duke Ellington’s, the new 9:30 was a hit, and it’s still hosting of-the-moment bands and big crowds today. “I thought it would take time,” says Hurwitz. “I thought the word would have to get out. But no. The second we opened, that was it: This is where everyone wanted to play.”

This article appears in the July 2022 issue of Washingtonian.