When the electrifying word came in January 1984 that Democratic presidential candidate Jesse Jackson had talked the Syrians into the release of downed American flier Lieutenant Robert Goodman and was bringing him to Washington, Marion Barry was basking in the sun on Barbados. He needed to get home quickly.

Barry managed to find a late plane to New York, but it was delayed and arrived after the last evening flight to DC. The only way home was a redeye-special Greyhound bus. He arrived at the bus station platform just in time to catch it, but too late to phone his 24-hour command center to alert the staff of his predawn arrival. At Newark he pleaded with the bus driver to allow him to exit for a phone call.

Leave the bus, Barry was told by the driver, and you take your chance that the bus will leave you.

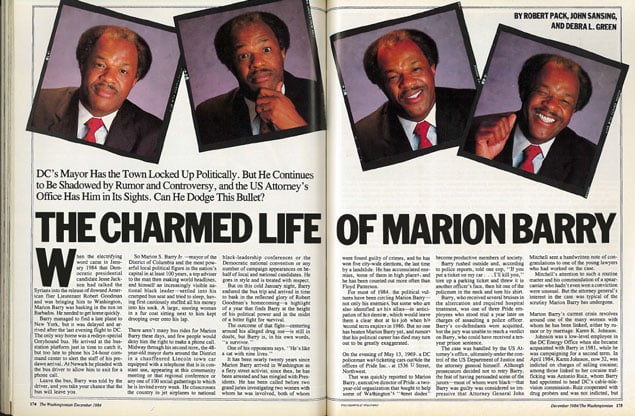

So Marion S. Barry Jr.—mayor of the District of Columbia and the most powerful local political figure in the nation’s capital in at least 100 years, a top adviser to the man then making world headlines, and himself an increasingly visible national black leader—settled into his cramped bus seat and tried to sleep, having first cautiously stuffed all his money into his sock. A large, snoring woman in a fur coat sitting next to him kept drooping over onto his lap.

• • •

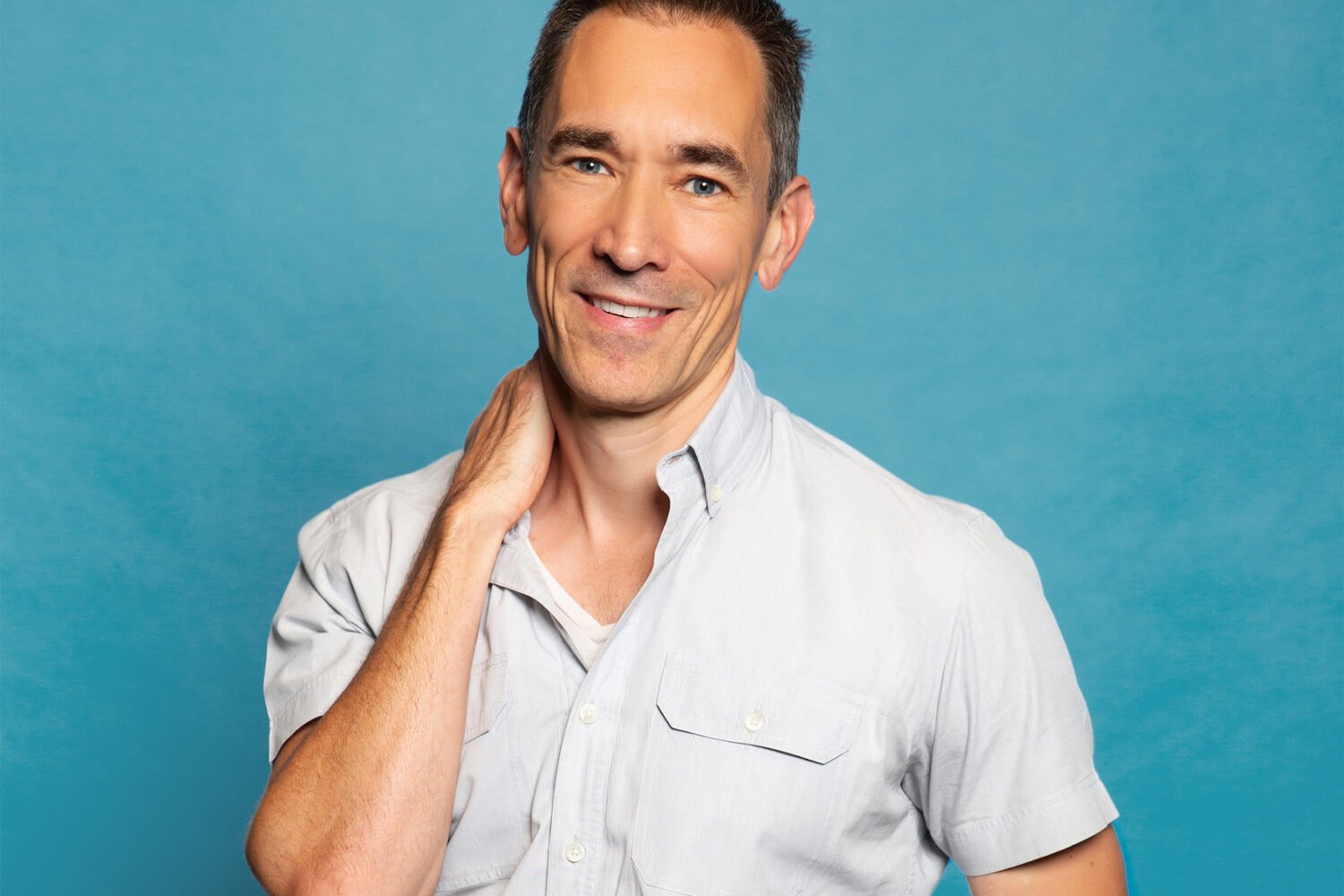

There aren’t many bus rides for Marion Barry these days, and few people would deny him the right to make a phone call. Midway through his second term, the 48- year-old mayor darts around the District in a chauffeured Lincoln town car equipped with a telephone that is in constant use, appearing at this community meeting or that regional conference or any one of 100 social gatherings to which he is invited every week. He crisscrosses the country in jet airplanes to national black-leadership conferences or the Democratic national convention or any number of campaign appearances on behalf of local and national candidates. He goes in style and is treated with respect.

But on this cold January night, Barry endured the bus trip and arrived in time to bask in the reflected glory of Robert Goodman’s homecoming—a highlight of a year that finds Barry at the height of his political power and in the midst of a bitter fight for survival.

The outcome of that fight—centering around his alleged drug use—is still in doubt, but Barry is, in his own words, “a survivor.”

One of his opponents says, “He’s like a cat with nine lives.”

It has been nearly twenty years since Marion Barry arrived in Washington as a fiery street activist; since then, he has been arrested and has mingled with Presidents. He has been called before two grand juries investigating two women with whom he was involved, both of whom were found guilty of crimes, and he has won five city-wide elections, the last time by a landslide. He has accumulated enemies, some of them in high place , and he has been counted out more often than Floyd Patterson.

For most of 1984, the political vultures have been circling Marion Barry—not only his enemies, but some who are also identified as his allies—in anticipation of his demise, which would leave them a clear shot at his job when his second term expires in 1986. But no one has beaten Marion Barry yet, and rumors that his political career has died may turn out to be greatly exaggerated.

• • •

On the evening of May 13, 1969, a DC policeman was ticketing cars outside the offices of Pride Inc., at 1536 U Street, Northwest.

That was quickly reported to Marion Barry, executive director of Pride, a two-year-old organization that sought to help some of Washington’s “street dudes” become productive members of society. Barry rushed outside and, according to police reports, told one cop, “If you put a ticket on my car . .. I’ll kill you,” tore up a parking ticket and threw it in another officer’s face, then hit one of the policmen in the neck and tore his shirt.

Barry, who received several bruises in the altercation and required hospital treatment, was one of three Pride employees who stood trial a year later on charges of assaulting a police officer. Barry’s co-defendants were acquitted, but the jury was unable to reach a verdict on Barry, who could have received a ten-year prison sentence.

The case was handled by the US Attorney’s office, ultimately under the control of the US Department of Justice and the attorney general himself. Although prosecutors decided not to retry Barry, the feat of having persuaded some of the jurors—most of whom were black—that Barry was guilty was considered so impressive that Attorney General John Mitchell sent a handwritten note of congratulations to one of the young lawyers who had worked on the case.

Mitchell’s attention to such a routine matter and his commendation of a spear-carrier who hadn’t even won a conviction were unusual. But the attorney general’s interest in the case was typical of the scrutiny Marion Barry has undergone.

• • •

Marion Barry’s current crisis revolves around one of the many women with whom he has been linked, either by rumor or by marriage: Karen K. Johnson.

Johnson was a low-level employee in the DC Energy Office when she became acquainted with Barry in 1981, while he was campaigning for a second term. In April1984, Karen Johnson, now 32, was indicted on charges of selling cocaine; among those linked to her cocaine trafficking was Antonio Ruiz, whom Barry had appointed to head DC’s cable-television commission Ruiz cooperated with drug probers and was not indicted, but he did resign his city post.

Barry claimed that he knew Johnson only “vaguely” and insisted that he had never used cocaine or known that Johnson dealt in drugs.

Subsequently, Barry admitted through his attorney, Howard University law professor Herbert 0. Reid- that instead of knowing Johnson only “vaguely,” he “knew her personally and . . . visited her in her apartment on and off over a period of twelve to eighteen months.” He continues to deny that he had a sexual relationship with Johnson, who had a son in the spring of 1983.

A former boyfriend of Johnson’s produced a tape recording, in which Johnson, not knowing she was being recorded, said she had sold cocaine to “an individual” 20 to 30 times between late 1981 and late 1982. Government sources made it clear that the “individual” was the mayor.

Barry was called before the grand jury to answer questions about Johnson but was not charged with any crime.

• • •

The prosecution presented evidence that Johnson had sold cocaine to at least six people on several dozen occasions between early 1981 and June 1983, and Johnson pleaded guilty to possessing and conspiring to sell cocaine.

She began serving a four-month jail term in August, but several days later she was called before a federal grand jury probing allegations of drug use by city employees. Granted immunity from prosecution, Johnson refused to testify before the grand jury and was sentenced to up to eighteen months in jail for contempt of court.

”Federal law-enforcement officials” subsequently told the New York Times that Barry might be charged with perjury for telling the grand jury that he had never used cocaine. In other words, prosecutors couldn’t prove that he had used cocaine, but they hoped to prove that he had lied when he denied it.

“They can’t convict me on anything,” Barry declared during an interview with The Washingtonian.

“You can’t find anybody that is credible, not these junkies and pimps out there who will use my name in vain anytime they can find a way to use it trying to get their ass off. ‘ ‘

Speculating that “Karen’s silence has to do more with suppliers than anything else–it’s a dangerous business out there,” the mayor insists: “I don’t need them [drugs]. If I did, I couldn’t function as well as I do. I’m too alert and too energetic and got too much sense and [am] too bright to have to be messing around with that stuff.”

• • •

Marion Barry believes in winning by confrontation, and lately he has had all the confrontation he could ever want. In the opposite comer is the US Attorney for the District of Columbia, the 39-year-old Republican Joseph diGenova.

DiGenova is in charge of the Karen Johnson investigation, as well as an ongoing probe into the conduct of the Barry administration in the Bates Street housing- development project. Barry feels that diGenova is playing dirty pool, leaking to the press allegations he can’t prove in court, perhaps in hopes of positioning himself to be appointed a federal judge.

Furthermore, Barry is convinced that the leaks are a family affair, originating with both diGenova and his wife, Victoria Toensing, a deputy assistant attorney general who is high in the ranks of the criminal division of the US Department of Justice.

Barry believes the New York Times was telling the truth when it attributed its perjury story to federal law-enforcement officials—i.e., the Justice Department. He thinks the basis for the story was a memorandum from the US Attorney’s office to the Justice Department outlining why there was not enough evidence to indict him for lying to the Karen Johnson grand jury. And he is not happy about the embarrassment that story caused him.

Shortly after the Times printed its article, Barry’s staff studied that and other stories, analyzing where the leaks had come from. Then Barry’s attorney, Herbert Reid, wrote a letter to diGenova’s boss, Attorney General William French Smith, asking for the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate ”the possible personal involvement of the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia.” To date, Smith has taken no action.

Barry and his advisers are also considering filing a civil suit against diGenova and others, seeking compensation for damage to the mayor’s reputation.

The purpose of the suit, according to informed sources, is not so much to win any money as to force diGenova to testify under oath.

On the other hand, says one source in the Barry camp, “If they’re willing to quit and go home, we are, too.”

DiGenova says Barry’s allegations that he is the source of leaks are ”baseless and totally false.” Victoria Toensing also denies any involvement, adding that Barry’s “scurrilous attack on my integrity is outrageous.”

• • •

If Barry survives this latest challenge, it will be yet another victory in a charmed life. The only bullet Marion Barry never dodged was one that struck him in the chest in 1977 during a terrorist takeover of the District Building, and even that wound was superficial enough that those associated with the surgical removal of the pellet referred to the then-city-council member as “Flick-it-out Barry.” So far, he’s been a very lucky man.

Barry points out that he’s a Pisces and describes himself as sensitive and compassionate. But then he notes that Pisces are often labeled “wishy-washy. People say they equivocate-one fish [on the Pisces symbol] going one way, one the other way. I describe it differently: top fish and bottom fish. I’m the top fish.

“Some people say that I’m too arrogant: I don’t think so. That I’m too self-assured: I don’t think so. I think you’ve got to be that way in order to survive in this society. If a person isn’t that way, the people around them won’t be self-assured and confident, either. If you act weak, they’ll act weak.”

Marion Barry, self-assured and confident, relaxes over a glass of Hennessey Cognac in a small alcove in the living room of his four-bedroom house on Suitland Road, Southeast, and reflects upon the unenviable consequences of public life: “There’s a rumor a minute about me.”

The house itself has been a source of controversy. He and his wife, Effi, bought the home in 1979, after living for two years in a rented rowhouse on E Street, Northeast, on Capitol Hill.

The couple paid $125,000 for the nine-year-old brick colonial in Capitol Heights, including a $100,000 mortgage from Independence Federal Savings and Loan, run by Barry’s friend William Fitzgerald, who had placed Effi on the board of directors. The loan was granted at 8.75 percent a year, well under the market rate and below the 12 percent Barry originally claimed he was paying. Publicity forced Barry to pay the higher rate, and Effi subsequently resigned from her $4,200-a-year directorship.

Another controversy arose when a high security fence was constructed in the back yard, a move that Barry maintains he resisted, knowing that he would be accused of shutting out the city at taxpayers’ expense. His security people insisted on it after Effi came downstairs one morning to find a stranger at the breakfast table—an irate ex-policeman seeking redress for being fired.

Not many members of the press have been welcomed into the home, partly because Effi strongly believes their house is a private matter and partly because for the first few years it was mostly unfurnished. Until a year ago, the living room was empty, save for a rust-colored wall-to-wall carpet, several throw pillows in front of the fireplace, and plants that Barry picks up wherever he goes.

Except for a few close friends, Effi Barry was reluctant to entertain until her home was ”just right,” says her husband. Now the living room is well furnished, with a large, salmon-colored sofa and Oriental rugs laid over the carpet. There are paintings of scenes from the Caribbean, a portrait of a golden-skinned nude looking coyly over her shoulder, and a number of African artifacts.

• • •

The mayor’s real at-home retreat is his basement, which also has a fireplace and is equipped with a green felt-topped poker table. The mayor proudly shows off the fancy casino-style card table, a recent acquisition that replaced a rickety old table he said was held together with tape. Playing cards as often as possible, now down to about twice a month, is Barry’s primary form of relaxation. Regular participants include two former aides, Ivanhoe Donaldson and Elijah Rogers; Jim Palmer, director of the DC Department of Corrections; Bill Fitzgerald of Independence Savings and Loan; and several others.

The game rotates among the homes of the players, the stakes are low—nickel, dime, and dollar betting limit—and the one rule is ”you never discuss business” at the poker table. Although the atmosphere is informal, Barry is generally addressed by his friends as “Mr. Mayor.”

Even Ivanhoe Donaldson, chief aide and confidant since Barry’s first city-council race, seldom calls him “Marion,” usually using “M.B.” or “Boss.”

Friendships in a public life as filled with demands and controversies as the mayor’s are hard to maintain. “I’ve talked with Effi about this ,” laments Marion Barry, “and I’m making a list of.several hundred people I’ve lost touch with.” Social events divorced from political events are rare.

But Barry does occasionally break away for fishing with some of the same buddies he sees at the card table. They go out in the Chesapeake Bay on a charter boat from Tilghman Island, and when the fish are running, as they were one day this fall, Barry is liable to come home with 50 bluefish and put them in a freezer in his basement. Other fishing friends: banker/developer Jeff Cohen, lawyer David Wilmot, and DC Department of Human Services head David Rivers.

• • •

The mayor loves seafood, but he usually has no choice at dinner; he eats five or six nights a week at civic or political banquets. His dining habits, which sometimes include ice cream for breakfast and heavy lunches at Mel Krupin’s, Duke Zeibert’s, J.J. Mellon’s, or the Hotel Washington, account for his growing paunch, which he pats ruefully. Says Donaldson, “The mayor has put on a lot of weight since taking office—most of it is because of nervous tension.”

Barry doesn’t exercise nearly as much as he’d like. He occasionally plays tennis in the early morning, but more often he skips it so as to be in his office by 9 AM. Those who have seen him play say he is no threat to John McEnroe—or, for that matter, Spiro Agnew.

The mayor’s diet and exercise have been important since late 1983, when he spent a week at Howard University Hospital after complaining of chest pains and shortness of breath. Fears that he had suffered a heart attack proved groundless; doctors found that he had a hiatal hernia that causes him discomfort from time to time. He has since been hospitalized twice with similar symptoms.

Barry’s doctors have told him to cut his workload, and he has ordered his staff to obtain his personal approval before scheduling anything for him on Sundays; he also talks of imposing the same restrictions on Saturdays. The demands on his time are constant, and Barry’s curtailed schedule is more hope than reality.

There is Eastern Standard Time and Marion Barry Time, which generally are about 45 minutes apart. “That’s one of my weaknesses, time,” he says. “I was born on the [Mississippi River] Delta; we didn’t have clocks down there. We told time by the sun- you had to look up,” he adds, raising his hand above his eyes as if searching for the sun. “So my body clock never really got right.”

Somewhere in Barry’s house may be one or two old dashikis that personified Marion Barry in the 1960s, but these days, Barry prefers pinstriped Christian Dior suits that he buys at end-of-the-season sales. He does most of his shopping at Raleighs on Connecticut Avenue, where his personal salesman lets him know when bargains are available and has eight or ten suits ready for inspection.

One Barry indulgence is ties; he estimates that he has 150. He buys five at a time, many of which his stylish wife dismisses as “terrible” and orders him to return to the store.

Barry says he does 98 percent of his shopping in the District, preferring that his sales taxes go to the coffers of his own government. ”I will not shop in Maryland or Virginia unless I have to.”

Barry makes a face as he mentions that his mother-in-law recently moved to Prince George’s County after living with him and his wife for eighteen months while she was going through a divorce. However, he brightens at the thought that Effi’s mother is only renting in Maryland and is planning to buy a place in DC.

Although his present salary is $74,500 a year, he still watches every penny. “People say most Pisces are cheapskates, hold on to every dollar,” remarks Barry. Perhaps he will never get over being poor, which he was for most of his life.

• • •

Marion Barry was born in the tiny town of Itta Bena, Mississippi, although he has told people on occasion that he was born in Memphis. His given name was Marion S. Barry Jr., but he adopted the middle name Shepilovk from a newspaper story while he was in college, where he discovered that, unlike his friends, he lacked a middle name. He has since reverted to the name he was born with.

Barry’s parents were a handyman named Marion Sr. and his wife, Mattie. “I was born with nothing,” says the mayor, who speaks about wearing shoes made from cardboard.

When Marion Jr. was four, his father died, and Mattie moved to Memphis along with her son and one daughter; another daughter went to Chicago to live with relatives. In Memphis, Barry’s mother worked as a domestic and married a butcher named Cummings, by whom she had two more daughters.

Memphis, where Barry grew up, was racially divided. He once recalled life there: “Memphis is similar to Mississippi in terms of attitudes of the people and police …. At the time I was growing up I could see quite a bit of segregation because buses, movies, schools, everything you could name in Memphis was segregated.”

Barry’s childhood, though impoverished, was full of accomplishment: Eagle Scout, newspaper carrier, good high school student. But he also spent weekend evenings shooting dice on street corners and pooling money for wine.

As a high school senior he applied to five predominantly black colleges and was accepted at every one; he turned down a partial scholarship at Morehouse College because it included a work-study program requiring him to pick tobacco to help pay his way. He had already picked enough cotton as a boy for 30 cents an hour, ten hours a day. Says Barry: “I sent them a letter saying, ‘Thanks, but no thanks.’ ” Instead he enrolled in LeMoyne College in Memphis.

• • •

At LeMoyne, Barry was vice president of the student government, treasurer of the senior class, and president of the school’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He was almost expelled after writing a letter to the school’s president protesting remarks by Walter Chandler, a white former mayor who served on LeMoyne’s board of trustees. Chandler, an attorney, represented the city of Memphis in a bus-desegregation suit, and he said in court that “the Negro should be treated as the little brother.”

Barry demanded in his letter that Chandler retract his comments or resign from the LeMoyne board; a Memphis newspaper published the letter. It was but the first controversy that Marion Barry would survive.

After graduation in 1958, the only member of his family to receive a college degree, Barry went on to Fisk University in Nashville, where he earned a master’s degree in chemistry, was active in the civil-rights movement, and helped found and was the first national chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a civil-rights group that was less patient with the status quo than the NAACP was.

After Fisk, Barry enrolled at the University of Kansas to study for his doctorate in chemistry, but he stayed only briefly, explaining later: “I had to leave. It was too quiet.”

From Kansas, Barry transferred to the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. There he helped start a black-oriented newspaper, the Knoxville Crusader, and was active in voter-registration drives in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. He also was one of the young turks who called for black students to boycott Mississippi high schools in 1961, which resulted in court-imposed fines of $255,000 against the NAACP.

• • •

While Barry was at Tennessee State University, his fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, gave a party and Barry met a young lady who struck his fancy—Blantie Charlesetta Evans. He kept asking her her name, suggested she give him a ride after the party, and finally persuaded her to reveal her phone number.

On March 3, 1962, three days before Barry’s 26th birthday, they were married in a Nashville church with many of their family members and friends on hand. His first wife recalls him saying, “You hang with me, you’ll be a First Lady.”

Blantie had a job in Nashville, and Barry was content for her to live there with her parents while he attended school in Knoxville. In June 1964, Barry “disappeared,” leaving his wife “impoverished,” according to a divorce suit that she filed in 1969. Her divorce was granted by a judge who found that Barry had “abandoned” her.

Looking back, Barry’s first wife explains the split: ”We had different ideas, and I probably didn’t fit with his. He was wrapped up in sit-ins, and I wasn’t geared in that direction.”

Today, remarried, living next door to where she did shortly after Barry left her, and working in employment security for the state of Tennessee, the former Blantie Barry bears Marion no ill will. For his part, Barry ignores his first marriage; when he married Effi in 1978, he said he had been married just once, to Mary Treadwell.

From Tennessee, Barry moved to New York, where he was an organizer for SNCC. In the spring of 1965, Washington activists were dissatisfied with SNCC’s operation here, and they launched a search for someone to improve it. There was general agreement, recalls one of those involved in the decision, that because of his leadership skills ”the guy to do that was Marion Barry.”

• • •

Arriving here in June 1965, Barry quickly attracted attention by leading the Free DC Movement, which advocated home rule and “solicited” donations from the city’s major businesses by ” suggesting” that they give their “fair share” to the campaign or run the risk of being picketed and boycotted.

He added to his notoriety by calling DC police an “occupation army” and “a military operation that must make many totalitarian states green with envy”; declaring that blacks were ” at war with ‘The Man'”; organizing a “mancott” of city buses to protest fare increases; and predicting after the 1968 riots that white-owned stores in the ghetto might “bum again” unless merchants turned over 51 percent of their businesses to blacks.

Ivanhoe Donaldson, who knew Barry slightly in those days and who would later become architect of his political victories, sums it up: “Clearly, Marion was a radical.”

But Barry’s bark was worse than his bite: He quit SNCC, in part because he felt it was becoming too militant, in part because SNCC leaders in Atlanta wanted him to spend more time raising funds for the national organization, while Barry chose to involve himself in DC issues. Nevertheless, at his inauguration as mayor in 1979, Barry introduced James Forman, former executive director of SNCC, as his “mentor.”

As time went by , Barry’s rhetoric cooled down. He did spots on the radio to recruit blacks for the police department he had previously professed to despise. Perhaps surprising to both of them, he formed a close friendship with Jim Palmer, a US marshal who was well connected with the black elite of prominent educators, lawyers, and doctors.

Palmer recalls: “He liked to talk with people—with everybody. He was a person who wanted to achieve a lot, and he tried to move very fast.” Palmer subsequently rose to head the US marshal’s office for the District of Columbia, and is now chief of the DC Department of Corrections.

Barry also was one of a group of activists who met nearly every Saturday with US Secretary of Labor Willard Wirtz. Among those who participated in the discussions of DC problems with Wirtz were Sterling Tucker of the Urban League, the Reverend David Eaton, the Reverend Walter Fauntroy, and David Rusk, son of former Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

One of the topics touched on was how to reach DC’s thousands of black youths, many of whom were poorly educated and unemployed. Barry criticized one plan; Wirtz shot back, “Do you think you can do better?” Barry said he could; and Wirtz provided $300,000 in August 1967 to launch Youth Pride Inc. This group evolved into Pride Inc., which served as a political springboard for Barry.

• • •

Pride Inc. put thousands of inner-city teenagers and young adults to work cleaning the streets, painting buildings, landscaping, and operating gas stations. Barry initially shared power at Pride Inc. with two other men, but soon Barry and a woman named Mary Treadwell were running the show.

Barry and Mary Treadwell met while both were students at Fisk in the late 1950s. After an unhappy marriage to a naval officer, Treadwell moved to Washington in 1966. Their involvement in protest activities brought Barry and Treadwell together. They began a relationship at Pride that resulted in their marriage in 1972.

Virtually from day one, allegations that large sums of federal money were lining the pockets of Pride leaders and anonymous letters questioning the morality of the group’s officials attracted the interest of investigators from the Labor Department, the FBI, the Internal Revenue Service, and the US Attorney’s office.

Finally, in 1982, six years after Barry and Treadwell had split up and more than a decade after Barry had left the organization to run for public office, Treadwell was indicted for looting federal funds from the Clifton Terrace apartment development, which a Pride company had purchased in 1974 with the help of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Among those indicted with Treadwell were her third husband, accountant Ronald Williams, and her sister, Joan Booth, both of whom had been on the Pride payroll. There were indications that Treadwell had also diverted Pride funds to her father, a building contractor, but the obvious target of the investigation into Pride’s affairs was a former member of her family, Marion Barry.

Even though Barry had expressed his disapproval of the Clifton Terrace purchase, and even though he had phased out of Pride by then to serve on the DC school board and to run for city council, the word around town was that Barry could not survive the Pride investigation.

Barry insisted on his innocence and pointed out that he and Treadwell had filed separate tax returns during their marriage. Barry’s detractors wondered how he could have failed to note that his wife’s $23,000-a-year salary from Pride could hardly pay for her Mercedes, the Volvo she bought for him, trips to the Caribbean, jewelry, and art. Even Barry’s friends doubted that very many people would believe his claims that he had not been involved in the Pride scandal.

But the prosecutors and federal agents who spent three years investigating Pride’s affairs could not lay a glove on Marion Barry. Neither could Mary Treadwell, who tried to make a deal in exchange for ”her knowledge concerning political figures,” according to government documents. Neither could the Washington Post, which was forced to include near the start of every story about Pride the phrase, “Barry was not in any way implicated.”

The Post may have been so zealous in its pursuit of Barry that it helped him. According to someone familiar with the prosecution of the Pride case, Post reporters preparing the series of articles that first brought the scandal to public attention promised anonymity to key sources and then attributed their comments to them, causing the sources to become uncooperative. Post staffers interfered to such an extent in the Pride case that prosecutors considered filing obstruction-of-justice charges against some of them.

Furthermore, targets of the Pride investigation were being tipped off by law-enforcement people. “The courthouse was not secure,” recalls one person involved in the investigation, and prosecutors finally insisted that no one except those directly involved in the case could have keys to the rooms where evidence was stored. In particular, government attorneys distrusted the US marshal’s office.

Treadwell was convicted of conspiring to defraud the federal government and making false statements to federal officials about Clifton Terrace. She received three years in prison and a fine of $40,000, a sentence she is now appealing. And Marion Barry emerged untouched—neither indicted by the government nor implicated by testimony. One law-enforcement officer who managed to infiltrate Pride with an undercover informant in hopes of getting the goods on Barry had this to say: “Above all, remember that Barry lands on his feet. He’s done it time after time.”

• • •

Nowhere is Marion Barry’s good fortune more evident than in his political career. He is fond of pointing out that he has been the underdog in practically every race he has run.

In February 1970, two and a half years after the founding of Pride, Barry was elected to a police advisory board, and in 1971 he made his first bid for a major office, a seat on the DC School Board. He ran against an entrenched incumbent, Anita Allen; she dismissed him as a “dude” who had traded his dashiki for a business suit in order to gain favor with the establishment.

Despite being a relative outsider, Barry upset Allen , scoring heavily with black and low-income voters. Three years later Barry began demonstrating his appeal to whites, who helped him finish a close second in a seventeen-candidate race for four at-large seats on the DC City Council. He was overwhelmingly re-elected to the council in 1976.

But it was Barry’s first race for mayor in 1978 that produced his most dramatic upset victory.

In the Democratic primary that September, incumbent Walter Washington sought re-election, with city-council chairman Sterling Tucker his main challenger. Tucker was backed by the Reverend Walter Fauntroy, DC’s delegate to Congress, and other Democratic leaders dissatisfied with the administration of Walter Washington.

The opposition to Mayor Washington wanted Barry to wait his turn and give Tucker a clear shot at the mayor’s job. But Barry had already stepped aside once for Tucker; Barry had wanted to run for council chairman in 197 4, but had bowed out in favor of Tucker.

• • •

Barry surprised everyone with a narrow victory, built on a key endorsement from the Washington Post, masterful political strategy by campaign manager Ivanhoe Donaldson, and a jerry-built coalition of liberal whites, Hispanics, and gays.

Barry also benefited from a move by the Tucker forces to get him to quit the race in exchange for a key job. Barry aides still refer to what happened as ”the caper”: Barry initially indicated he was willing to discuss the Tucker offer, but Barry failed to show up at a late-night meeting with Tucker and other political leaders, refused to bow out of the race, and managed to make it appear to the public that he had been the intended victim of a cynical political deal. The outcome was practically a triple dead heat, with Barry first, barely ahead of Tucker, and Washington third.

A break for Barry was that DC election laws do not require a runoff if one candidate receives less than 50 percent of the vote; Barry’s 34 percent was enough to get him into the general election against Republican Arthur Fletcher. Had a runoff been necessary, it is likely that Tucker would have drawn more Walter Washington voters than Barry would have, gaining Tucker the Democratic nomination.

Many stories about Barry’s personal life and his involvement with Pride made the rounds during that 1978 campaign. Arthur Fletcher, his GOP opponent, says that nearly every night between midnight and 4 AM, “my mailbox would fill up with junk about Marion Barry.” Fletcher said none of the information could be confirmed, and he never used any of it in his race against Barry.

Barry won the general election by a margin of more than 2 to 1, making him the first mayor of a large US city to have come from the militant wing of the civil-rights struggle.

• • •

When Barry ran for a second term in 1982, he began as an underdog and again had good fortune on his side. An Associated Press-WRC-TV poll taken that May put Barry eleven points behind his main Democratic challenger, Patricia Roberts Harris, who had been Secretary of HUD in the Carter administration.

About two weeks before the September primary, the Harris campaign received a tip that there was a scandal at the Bates Street housing-redevelopment project, and that Barry was involved.

Harris campaign aides tried frantically to pin something on Barry in the short time before election day. According to an informed source, city funds had been shuffled through “a maze of corporate structures that defies the imagination of corporate lawyers and con men alike,” and $4.3 million was missing. But Harris aides were unable to link Barry to any wrongdoing.

On election day Barry trounced Harris with 58 percent of the vote to her 36 percent, with city-council members John Ray and Charlene Drew Jarvis dividing the other 6 percent. Barry went on to beat his Republican opponent, E. Brooke Lee, easily in the general election in November.

Following the primary, Harris staffers turned over their Bates Street findings to the FBI. A federal grand jury continues to investigate the project.

Once again there is talk that this may be the end for Marion Barry, but the rumors, as usual, have produced no tangible results.

The allegations about Barry’s personal life and his supposed involvement in Bates Street may turn out to be a lucky break for him, according to a political foe, councilmember John Wilson, who predicts Barry may receive a sympathy vote if he runs for re-election in 1986. “It’s a bitch fighting someone with nine lives,” declares Wilson.

• • •

When Walter Washington was mayor, he had formidable politicians such as Marion Barry and Sterling Tucker stalking him. For Marion Barry, the best news politically is that there is no one like Marion Barry on the scene to challenge him in 1986.

John Wilson is conducting polling now on his chances in 1986 and looking around for sources of campaign money. As the city council’s most vocal independent, he could serve as a rallying point for the anti-Barry forces , and his tactic of immersing himself in the financial side of DC government is not unlike Barry’s route to power. But many feel that Wilson is an unpredictable maverick who will not be able to assemble a winning coalition.

Former DC school superintendent Vincent Reed, a nominal Republican who could easily switch to the Democratic party, is often mentioned. The popular Reed would be Barry’s most formidable opponent, but Reed is said to be content with a well-paying, highly visible position as vice president for community relations at the Washington Post. And friends say he lacks the stomach for the rough campaign that would occur.

Who else? Betty”Ann Kane tried valiantly in 1982, but it didn’t take. Another potential candidate, David Clarke, is probably content to be city-council chairman. If either one ran for mayor, it might raise questions as to whether the city would suffer from a white-black confrontation, even from a white like Clarke or Kane with impeccable credentials in the civil-rights movement.

Barry’s political power is even more striking when one realizes that there has been a reversal in his basic constituency. Barry barely made it into office in 1978 on a coalition of outsiders—Ward Three whites, preservationists, gays, Hispanics, the activist poor. Barry himself was an outsider, fighting the candidate of business and the black elite—Sterling Tucker—and the candidate of the conservative, middle-class churchgoers—Walter Washington.

Of those groups, the gays are still with Barry; he has courted them assiduously. Preservationists feel left out; the Barry administration is now perceived as favoring development over historic preservation. Barry did not fight hard against the cause celebre of the preservationists, the demolition of Rhodes Tavern in favor of Oliver T. Carr’s Metropolitan Square, and he is suspected of having worked behind the scenes with the Carr forces, attempting to head off a voter referendum on the question.

And there is a feeling among a number of both whites and blacks in the District that Barry is too quick to make polarizing statements. Two recent examples: his reaction to the defeat of Republican city-council member Jerry Moore, a black, by a more conservative white, Carol Schwartz, in the Republican primary, and his hinting that racial motivation was behind the US Attorney’s current spate of investigations into his personal conduct. Admirers and enemies alike worry about this political tactic.

“Barry perhaps sees everything through this filter of race,” explains one former city official. “Perhaps he was singed by racism more than the rest of us.”

• • •

Defenders of Barry point out that he has generally been colorblind in personal relationships and in his key appointments. In his second administration, whites replaced blacks in two of the city’s most powerful positions: Thomas Downs succeeded Elijah Rogers as city administrator, and Betsy Reveal took over for Gladys Mack as budget director. Among Barry’s closest backers and advisers are several whites who have become friends as well, including restaurateur Stuart Long, real estate developer and banker Jeff Cohen, and advertising executive David Abramson.

Some liberal whites seem keenly disappointed with Barry- upset, for example, that he seems more concerned with a commercial-building boom than with public housing. One white quotes Saul Alinsky: “When the poor get power, they’ll be shits like everyone else.”

Barry has earned the grudging admiration of the business community, and he has solidified his strength among middle-class black churchgoers. Even the black elite failed to support one of their own, Pat Harris, in 1982. Barry is particularly proud of that 22-point victory: “I just killed her. ”

Furthermore, Barry has sewn up control of the local Democratic party; his former aide Ivanhoe Donaldson now heads it, and although Donaldson affects an independent pose, few people believe the party would go against Barry.

In sum, barring a prison sentence, Barry has a lock on his job. He remains coy about his desire to run in 1986, but there is no other significant local office available, and a national appointment would have to await the election of a Democratic President.

• • •

In 1978, when Barry was running for mayor, his net worth was just over $10,000. Today, nearing 50, Barry laments that he still has little wealth. Others in his circle—including his closest confidants—have gone on to harvest the rewards of public service. Ivanhoe Donaldson is an investment banker with E.F. Hutton, and Elijah Rogers is at the international corporate-accounting firm of Alexander Grant, both at salary levels exceeding that of the mayor.

Says Barry: ”There are 268 black mayors in the country and most of us, unlike the whites, are poor.” He has no savings or investments, and says he could make it only for a couple of months without a paycheck. And Barry likes to live well. His favorite place is the Caribbean islands, to which he manages to slip away whenever he can. He talks vaguely of starting a business in the private sector, and he has accumulated enough friendships and chits to have a good chance at whatever entrepreneurial venture he might pursue.

Leaving public life might have other attractions. Barry’s days and nights are so consumed by his official duties that he has little time for his wife and their four-year-old son, Christopher. Effi Barry has been known to complain that being married to the mayor isn’t much different from being single.

Throughout the seven years they have been married, there have been rumors about Barry’s involvement with other women, which Barry strongly denies. Certainly his public manner is one of flirtatious attention to any number of women, but Ivanhoe Donaldson states emphatically: “Whatever his personal adventures, he is intensely loyal to his family.”

Lately, Effi has withdrawn from much of public life, and when she appears she often seems to be under strain, a fact that the mayor attributes to a chronic pinched nerve in her neck.

One of her most glaring absences occurred in August, at a time when the mayor was beleaguered by press reports about his involvement with Karen Johnson and drugs. Supporters held an appreciation day for him at the Shiloh Baptist Church. Barry’s mother was flown in from Memphis for the event; Jesse Jackson’s wife represented him; young Christopher Barry was among the 500 people on hand to give support to the mayor. Noticeably missing was Effi Barry. Subsequently, the mayor’s office explained that she had been out of town on business.

During that same period, Effi Barry told a television reporter that her husband had decided to retire from public office, a statement Barry had to renounce, and she got into an embarrassing flap over her driving. She was ticketed for going over 80 on Shirley Highway in Arlington while at the wheel of her 1979 Cadillac with license plate DC-I, but she didn’t tell Barry until reporters asked him about it a week later. Mrs. Barry later pleaded guilty to speeding at 73 miles an hour and paid a fine of $36 plus court costs.

More recently, there have been rumors about Effi looking for an apartment at the Watergate, which Barry dismisses: “First of all, she can’t afford the Watergate. She can’t afford it; I can’t afford it.” He insists that they are making plans for their tenth wedding anniversary, three years hence.

One source of delight in the lives of Marion and Effi Barry is their son Christopher. The mayor dotes on his boy, and the household revolves around him. Because Effi Barry does not like to go out to the movies as often as her husband wants to, Barry often brings films home to watch on his videocassette recorder. But he finds that Christopher frequently has the TV set occupied with cartoons.

Even at work, Barry has Christopher on his mind; his office in the District Building is filled with toys in case his son should drop in. When Christopher was a crawler, Barry’s staff had to dodge him as he explored the ceremonial office and hallways within the mayor’s fifth-floor District Building suite.

Barry notes that many political spouses have problems. He blames the press for prying too much into his personal life, which he feels is his business as long as it doesn’t affect the way he performs his job.

Barry singles out the Washington Post as the news organization that has been least fair to him. He distinguishes between the editorial staff, which has been generally sympathetic, and city-side news reporters, whom he accuses of being ” unbalanced” in their coverage of the city and of getting mired in the “Watergate syndrome: Let’s find out how we can bag the mayor today.”

His little-love, mostly-hate relationship with the Post has affected his reading habits. Barry used to visit a neighborhood store just before midnight to pick up the paper’s first edition, but he found that what he read many nights made him so angry he had trouble sleeping. “So I stopped that nonsense. I said I’m not gonna let them keep me up at night. Not in my lifetime.”

Next Barry started getting up about 6:30 AM to read the Post that was delivered to his home, but he found that that ruined his early mornings. Now the mayor waits to read the paper until he arrives at his office, and even then he relies on his staff to cut up the Post and excise articles that will raise his dander.

• • •

Though there are many reasons why Marion Barry might be tired of public life, it is hard to imagine him not in a position of power and attention. He was born to the role of politician. He remembers faces and names by the thousands. He is—despite an insistence that he is shy—naturally gregarious and charming, with a dazzling smile, a warm voice that plays better in person than on television, and an ability to disarm strangers and co-opt adversaries. He is, like John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, a natural.

And he possesses that most desirable of political attributes: He is persistently underrated. Even critics admit that he is one of the most intelligent politicians on the scene today, with the ability to read and digest budgetary items, fiscal reports, and complex management problems. While his two administrations have had their share of triumphs and failures, no one says he has not been a strong, activist mayor. Few people in this city are neutral on the subject.

Perhaps in his current confrontations he has again been underrated; perhaps he will continue his charmed life.

Certainly he professes outward calm about the charges, the leaks, the rumors. He plunges onward in office, darting about the city and crisscrossing the country, seemingly unconcerned about his future. He dismisses it all casually: ”Why worry about bullshit?”

This article appears in the December 1984 issue of Washingtonian.