Playing Thursday, June 21, at 7:15 PM and Saturday, June 23, at 3 PM

In Ai Weiwei, 27-year-old first-time filmmaker

Alison Klayman has a subject most

documentarians and journalists can only dream of. The Chinese artist and

activist is eccentric, chatty,

an iconoclast, has a tangled personal life (three years ago he

had a son with a woman who isn’t his wife), and is utterly,

inexplicably charming.

In 2011, Chinese authorities arrested him, raided his

studio, and held him prisoner for 81 days, during which time museums

worldwide organized protests and petitions to have him freed.

Ai became a global symbol of the lack of freedom in modern China,

and his personal fame skyrocketed.

Klayman first starts following the artist in 2009,

while he’s investigating the casualties of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake

and infuriating authorities by helping compile a public list of

the 5,000-plus students who died thanks to shoddy “tofu” construction

in the city. Ai, it immediately becomes clear, is a world-class

troublemaker as well as a visionary artist. “I consider myself

more of a chess player,” he tells Klayman, who displays

pictures he took of himself giving the finger to locations such as

Tiananmen Square and the White House.

Ai is also that rarest of beasts: an artist who

understands social media. He blogs daily, takes hundreds of photographs a

day, and is greatly enamored of Twitter, which he pronounces,

rather sweetly, as “Tweeter.” Seemingly insulated from the Chinese

government by his fame, he nevertheless admits to Klayman that

he’s afraid of repercussions. “I am so fearful. That’s not

fearless. I act more brave because I know the danger is really

there.”

The film follows Ai to London, where he attends the

opening of his groundbreaking exhibition “Sunflower Seeds” at the Tate

Modern. We hear about his life as a young artist in New York

and his early work before he started outsourcing much of it (in

one scene, Klayman films Chinese artists crafting “Zodiac

Heads,” currently on display at the Hirshhorn).

Ai himself is a compelling enough subject to fill a

movie several times over, and all Klayman really has to do is let him

entertain us. But her narrative is taut, and when Ai is

unexpectedly arrested, seemingly as a warning to other outspoken

artists,

she captures the campaigns and the demands from high-profile

people such as

Hillary Clinton for his freedom.

She’s also there when he returns home, strangely

muted, telling reporters that regrettably he can’t comment, as he’s

technically

on bail. The sight of such a sadly chastened Ai is hard to

watch. Thankfully it isn’t long until he’s blogging again.

Inspirational,

curious, and optimistic in various degrees,

Never Sorry gives us an insightful, weighty look at one of the most fascinating figures in contemporary art.

—SOPHIE GILBERT

Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present

Playing Friday, June 22, at 10:15 PM and Saturday, June 23, at 10:30 AM

There’s no doubt that

Marina Abramovic, often called the grandmother of performance art, is a captivating personality, as evidenced in

Matthew Akers’s gripping and enchanting documentary,

Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present.

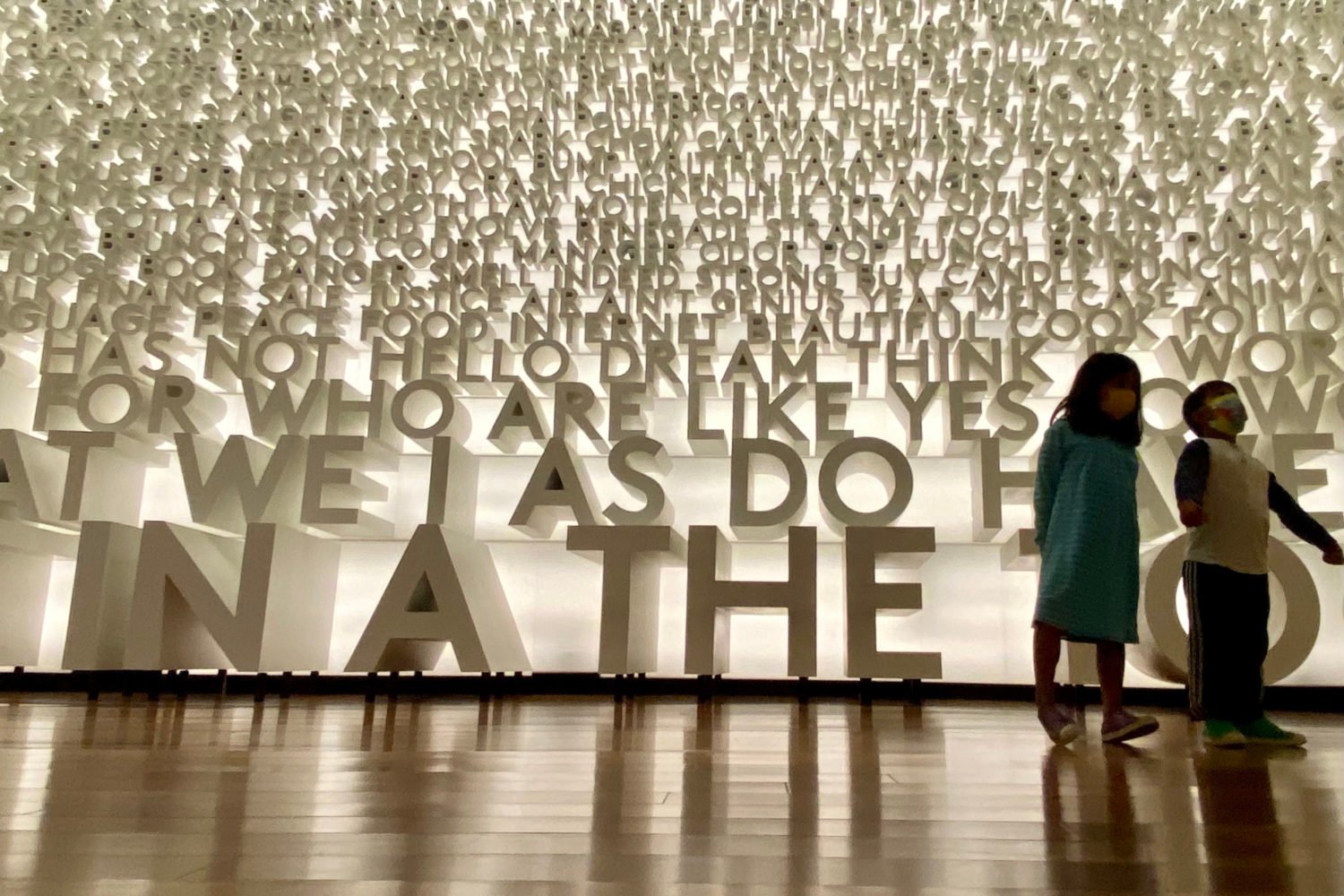

We meet up with Abramovic, now 63 years old, as she’s

prepping for perhaps the biggest show of her career, a 2010 installation

at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Known for her unusual

and visceral displays of human interaction, in which she predominantly

uses her own body to demonstrate pain, emotion, and the

sometimes raw physical effects of daily life, Abramovic has reached

a pivotal moment in these latter years of her artistic career.

With the support of the art community and her myriad fans,

she decides to install herself—quite literally—in a chair for

90 days, so she can come face-to-face with any number of strangers

who visit her at MOMA.

It’s a massive undertaking, one that requires

Abramovic to expel some demons and be irrepressibly present in the

lead-up,

all witnessed by the viewer during this intense and deeply

moving portrait of an artist at the precipice of her swan song.

As Abramovic says, performance art is is a “real” form of art,

wherein the very presence of the artist serves as the medium.

She “plays with the edge of the knife,” says her longtime

gallerist,

Sean Kelly, one of Abramovic’s earliest supporters. For Abramovic herself, this show is really about finally being acknowledged after

“40 years of people thinking you are insane.”

Filmed over a ten-month period, Akers’s movie captures

Abramovic’s most personal moments, from relaying her nervous energy

and stress as the opening nears to listening to her tell the

story of love lost with longtime companion and former collaborator

Ulay as tears stream down her face. When art is this personal,

this cerebrally challenging, one almost wants to roll one’s

eyes at the imposed seriousness of it all, but there’s

something about Abramovic that prevents the snickering and scoffing;

she is truly seductive and interesting, her honesty touching

and her physical stamina beyond impressive. Abramovic is surprisingly

vulnerable, almost uncomfortably so, which adds a very complex

juxtaposition to the cold and stark themes of her artistic

performances. You can’t help but like her.

The last third of the film focuses on the MOMA

installation, where we watch Abramovic sit, day after day, hour after

hour,

motionless, as hordes of people stream through the museum,

sitting just a couple of feet from her face, staring into her eyes,

some so overcome with emotion that they openly cry with the

sheer joy of being so close to her. With Abramovic’s commitment

to this bizarre journey, art becomes accessible—performance

art’s unfamiliar rhythm becomes familiar, simply due to the fact

that she is sitting right there.

All told, more than 750,000 people came through the exhibition during Abramovic’s three-month stay. If

The Artist is Present accomplishes anything, perhaps

it best serves to expose the complex nature of performance art, to argue

that it is more than

an exercise in navel-gazing narcissism, and that those wholly

committed to their artistic medium are truly fascinating subjects.

—KATE BENNETT

Playing Thursday, June 21, at 10 PM and Sunday, June 24, at 10:15 AM

Portrait of Wally is director

Andrew Shea’s compelling account of a Jewish family’s struggle to recover a painting that was stolen from them by the Nazis in 1939.

In 1997, the relatives of deceased art dealer

Lea Bondi were shocked to learn that Austrian painter

Egon Schiele’s “Portrait of Wally” was on

display at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The intimate portrait of

Schiele’s mistress had

been Bondi’s prize possession—hanging on the wall of her Vienna

home—until it was seized by Nazis as World War II got underway.

Bondi would spend the rest of her days trying to recover the

painting. But she never got it back.

After the Museum of Modern Art turned down the request of Bondi’s heirs to keep the painting in New York, District Attorney

Robert Morgenthau opened a criminal investigation of the matter, touching off a crisis within the art community and a legal battle over the

painting’s ownership that lasted more than a decade.

With a fast-paced narrative, Shea’s film explores the

painting’s provenance, the mysterious circumstances surrounding its

disappearance, and the uncomfortable questions that the

controversy precipitated for art galleries around the world. Whether

you’re an art enthusiast or not, the film has the drama and big

moral questions to keep you engaged.

—LUKE MULLINS