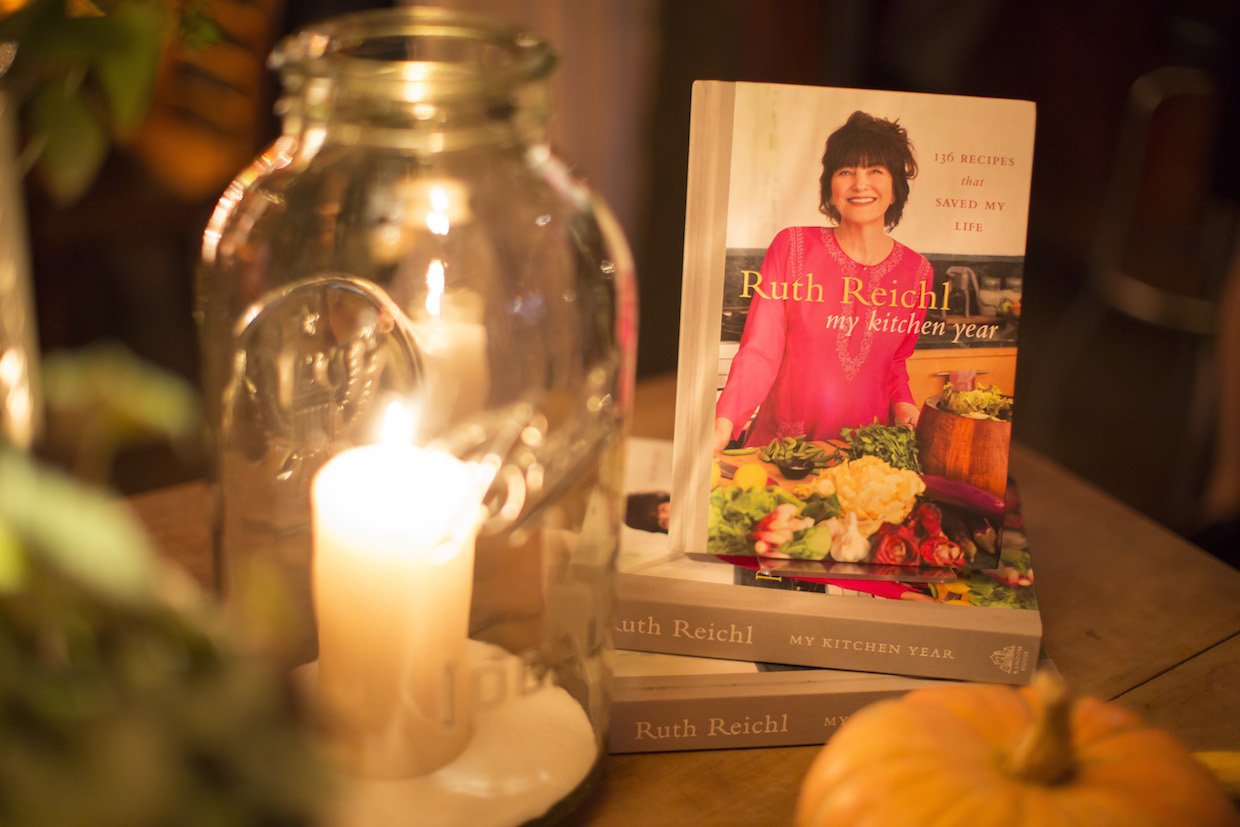

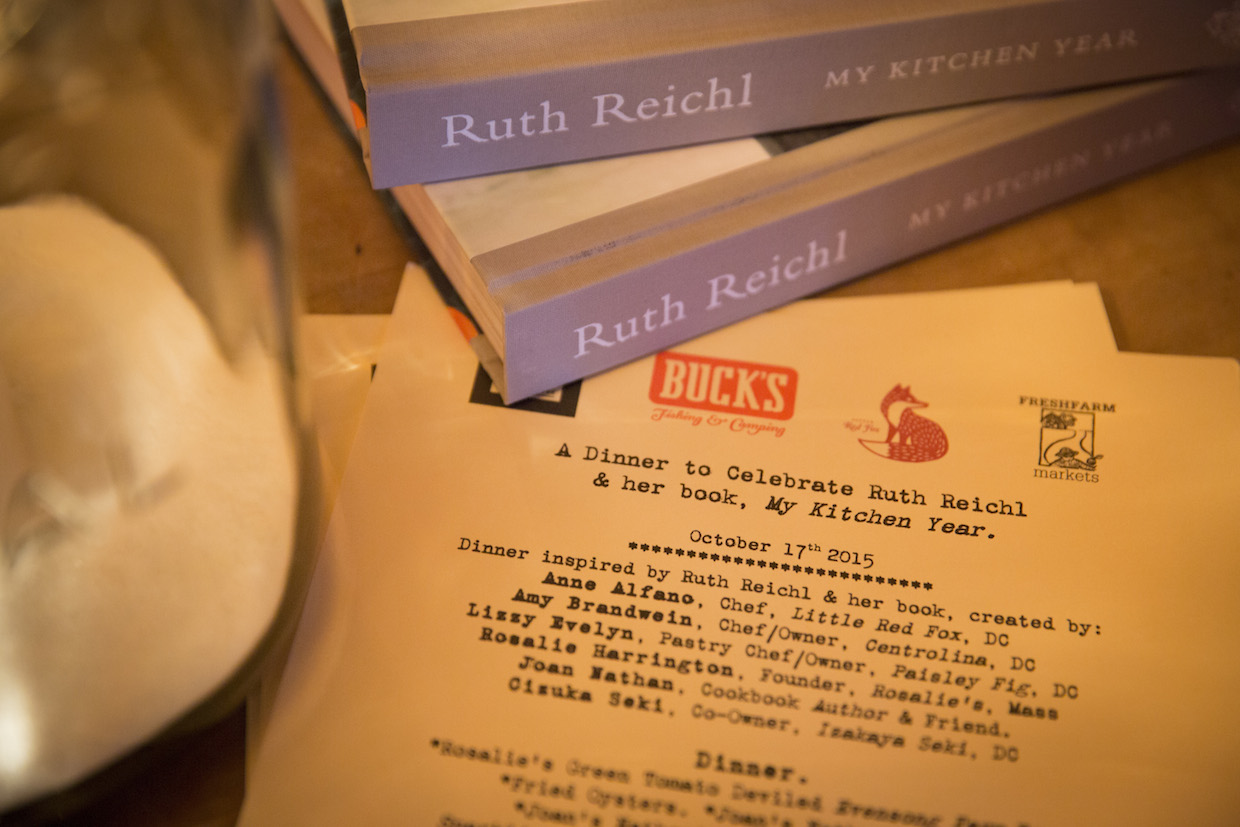

Ruth Reichl, the former editor in chief of Gourmet magazine, was craving fried oysters on a Saturday evening. Fortunately we were in a restaurant, Buck’s Fishing and Camping in Chevy Chase DC, and a team of Washington’s top female chefs had prepared a dinner inspired by recipes in Reichl’s newly-released book, My Kitchen Year: 136 Recipes That Saved My Life. On the menu: Joan Nathan’s chicken-liver pate, an Asian eggplant salad from Cizuka Seki (Izakaya Seki), and lucky for Reichl, fried oysters.

The ticketed event was part of an ongoing series with Buck’s owner James Alefantis and neighboring bookstore Politics & Prose, where touring authors in the culinary world invite fans to experience their work in the most intimate way possible: through a meal. Past visting chef/writers include Alice Waters and Gabrielle Hamilton. That’s not to say Reichl needs tangible food to connect with her readers. Guests arrived holding copies of her early memoirs, Tender at the Bone and Comfort Me with Apples, and repeatedly expressed thanks for her honest, personal approach, both then and now in My Kitchen Year. Though it’s a cookbook—Reichl’s first in 40 years—the linear narrative centers around the abrupt closure of Gourmet, and the months of cooking, contemplation, and coping with loss that followed.

“I was 62 and I honestly thought I was never going to get another job, that I was a failure,” said Reichl. “I’ve always defined myself by my job. I used to be ‘Ruth Reichl, comma, somebody.’ And now I’m ‘Ruth Reichl, comma, nothing.’”

Reichl said she expected her book to resonate with people of her own age who’d lost their jobs, as well as the many Gourmet devotees. She found one surprising result of her tour was the reactions from a broader spectrum of people.

“The way things are in America right now, there are a lot of young people who’re losing their jobs and who’re terrified in the same way I was,” said Reichl. “I’m meeting thirtysomethings who are telling me, ‘this book gives me hope.’ I knew objectively that the economy has changed, and people don’t expect to have their jobs for life anymore, but I’m seeing how it affects people’s psyches in a really profound way.”

For Reichl, the solution to being frightened—or confused, or lonely—is cooking, and the fruits of a turbulent time fill the cookbook’s pages: “easy bolognese” she made with friends after packing up her office, a bracing ma po tofu from the first day of unemployment, and a home cook-friendly version of Eric Ripert’s pasta with sea urchin that Reichl dreamed of while recovering from a foot injury. Centrolina chef/owner Amy Brandwein recreated the latter dish for the event, nudging it towards Ripert’s original by folding the uni directly into the dough, and serving it in the urchin’s shells that she spent hours hollowing out that morning.

“Making a meal from my book is complicated for chefs, because the recipes are really home-cooking,” said Reichl, who finally sat down to eat the pasta after circling Buck’s dining room, stopping to chat at every table. “These are not cheffy dishes.”

Reichl’s natural directness is likely what makes her dread one question the most—why Gourmet shuttered in 2009. She tells the story of the day she and her staff gathered for a meeting with Condé Nast chairman Si Newhouse.

“Si comes in, and this is the extent to what he said: ‘It’s very sad, but Gourmet is closed. End of story.’

My Kitchen Year begins with Reichl on tour, promoting the Gourmet cookbook in the weeks after the magazine folds. She’s bombarded with questions about why the 69 year-old institution was shuttered, and still gets them on tour to this day.

“The truth is: I don’t know,” said Reichl. “It’s a privately-held company. They didn’t have to tell anyone why they closed it, and they didn’t tell me. It’s the one I dread because people think I know, and I don’t.”

Look for more on the Gourmet years in Reichl’s next memoir, which will hopefully be accompanied by yet another meal.