Hany Hassan may be America’s least-conspicuous elite architect. Pick a prominent Washington destination and there’s a good chance he’s touched it in some way. He has shored up, added to, reimagined, or modernized a long list of famous places, including the US Capitol, the Kennedy Center, Arlington National Cemetery, and the Trump International Hotel.

And in contrast to, say, César Pelli’s addition to National Airport or I.M. Pei’s East Building for the National Gallery of Art, none of Hassan’s work has become closely associated with his name. Which is how he wants it. “Anything and everything I do, it’s not to create my own thing,” he tells me one recent afternoon at his Georgetown office. “It’s just about respecting what is there.”

Unlike most artists, in other words, Hassan is not on a mission to leave behind an obvious signature. What fulfills him is saving irreplaceable buildings, then making them easier for modern-day people to appreciate and enjoy.

Since emigrating from Egypt in 1978, Hassan has risen to become DC director of Beyer Blinder Belle, the New York–based firm renowned for renovating landmarks such as the Apollo Theater and Grand Central Terminal. He’s now also among the nation’s most sought-after architects for significant historic projects. Such as one of his latest works: the Washington Monument’s under-stated new visitor center, which opened in September.

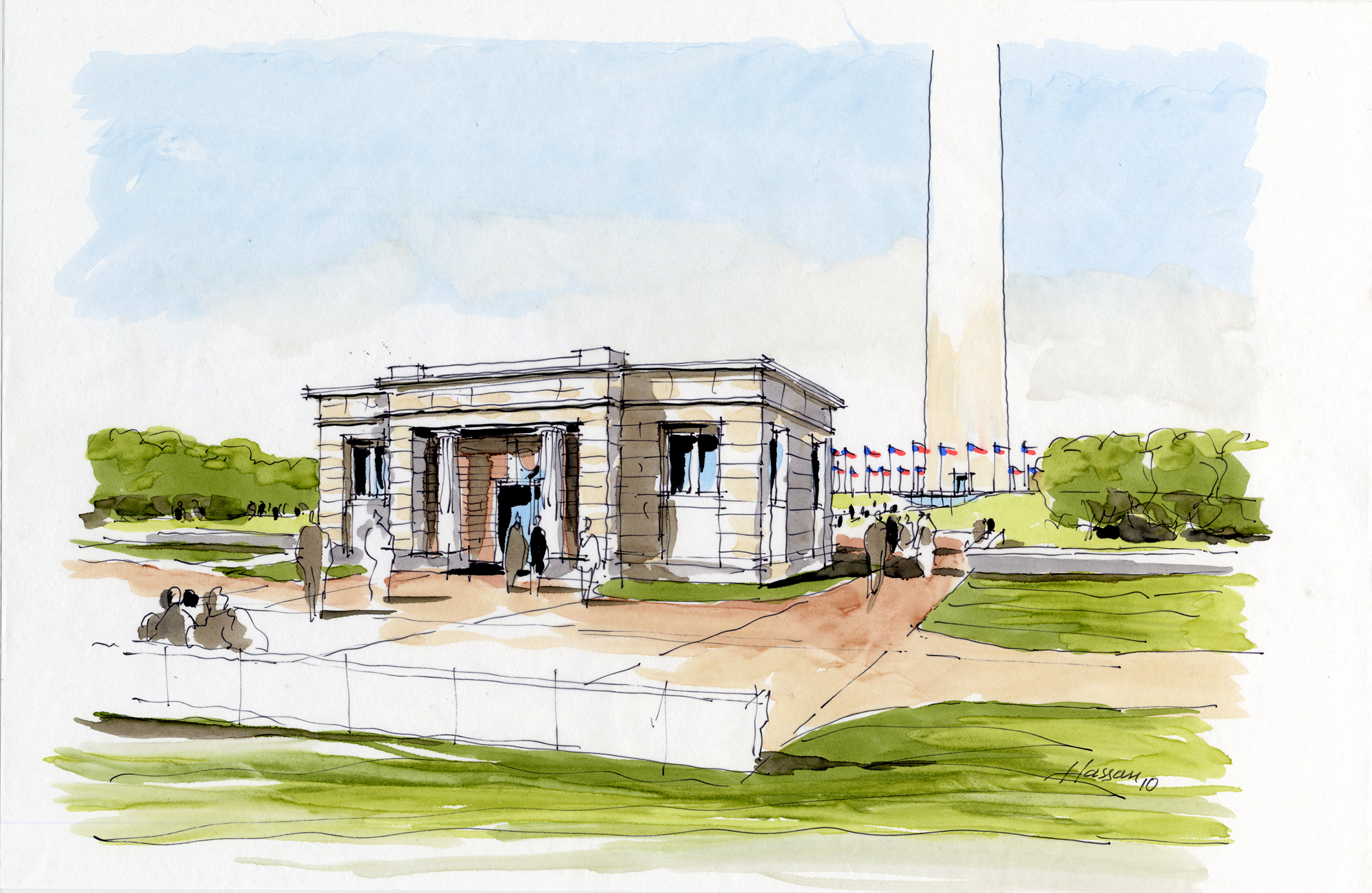

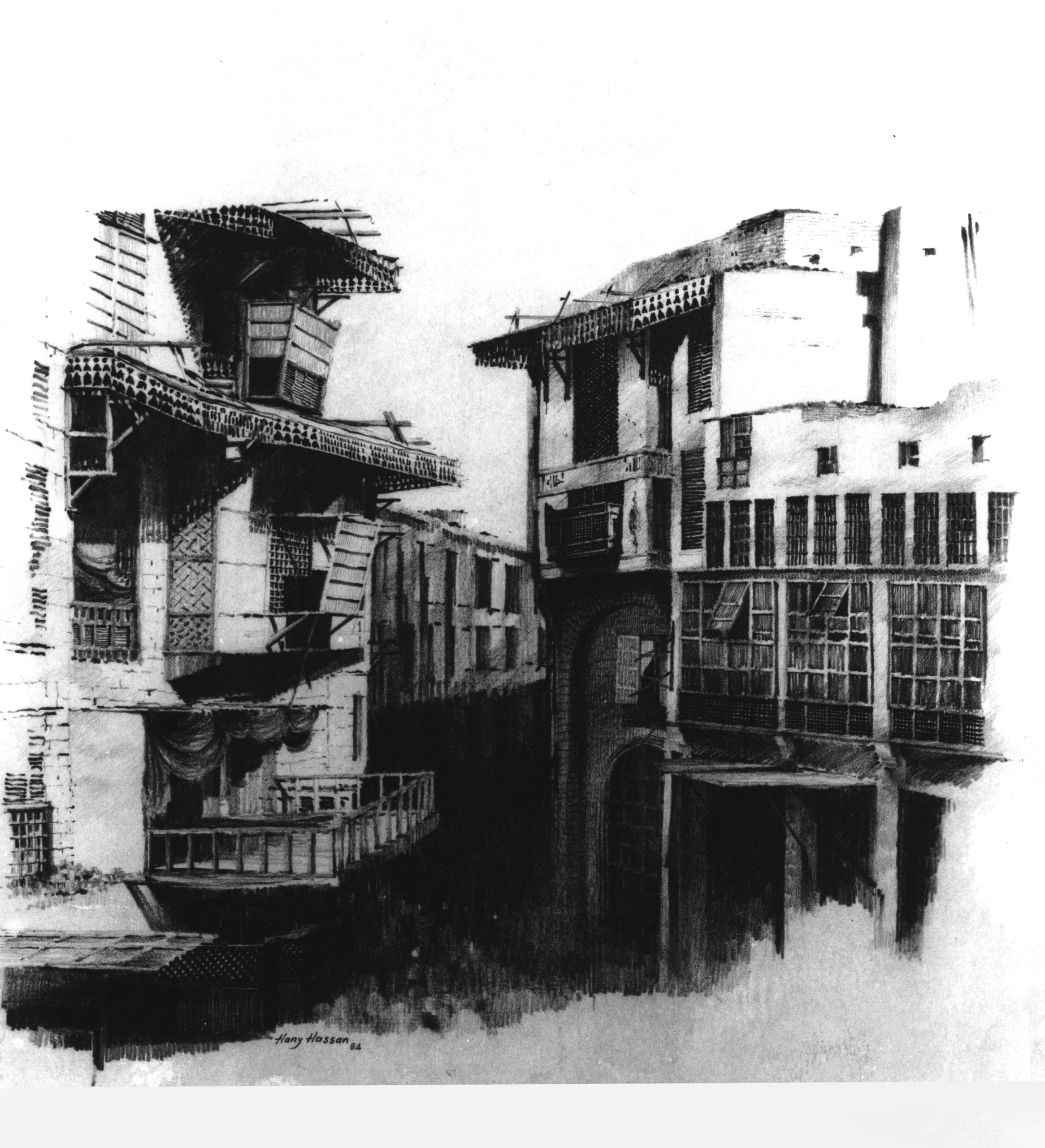

Sketches by By Hany Hassan.

Sketches by By Hany Hassan.

If it hasn’t yet caught your eye, Hassan will take that as a compliment. “If you walk by or drive by the monument, you never feel like there’s an addition to it,” he says. “It goes away in the landscape.”

It’s hard to think of a more perfect assignment for Hassan than upgrading this country’s best-known obelisk, a form that was one of ancient Egypt’s architectural gifts to the world. Hassan says the architecture of his youth in Cairo will always influence him. “Think of the pyramids as a structure—that pure, very simple form,” he says. “In that simplicity, there’s a lot of strength. That’s sort of guided all of my designs.”

For the Washington Monument’s visitor center, he essentially crafted a glass box, albeit an extremely sophisticated one. In contrast to the temporary trailer that was set up for security screenings after 9/11, the new space is meant to give people a “dignified experience,” Hassan says, even as they pass through metal detectors. Because it’s glass, the center feels bright and open; you can look up through its transparent ceiling and see the monument towering above. Sandwiched between those glass panels is a high-tech mesh that makes the structure ballistic-resistant. In the right light, the same mesh takes on an aesthetic role, giving the whole box a golden glow.

“I hope people feel that they are welcome and respected as they enter,” says Hassan of his design, which took a decade to realize. “They should not feel like they are being degraded.”

All this emphasis on creating a dignified reception makes me wonder if Hassan is speaking from personal experience—if, as an immigrant, he has endured the opposite type of reaction in this country. But he says he has never experienced discrimination. “I don’t think there is any place in the world that is more welcoming and more embracing and helpful to people than the United States,” he says. “I have never felt that I don’t belong here.”

After earning his architecture degree at Cairo University, where his father was dean of the engineering school, Hassan got an opportunity to move to New York for a job with the Eggers Group architecture firm. He hardly knew a word of English, relying on sketches and watercolors to communicate with colleagues. “I view drawing as the architect’s first language,” he says. “Everybody can understand it. It breaks through any barriers.” By 2000, his profile had risen enough that Beyer Blinder Belle asked him to move to Washington and open its office here.

As it happened, the capital proved a good fit for Hassan’s personality, which involves a calm demeanor and a willingness to compromise that, it’s safe to say, exceeds that of the average architecture star. That’s especially valuable in a city where so many projects have to grapple with historic preservation and a half dozen different regulators can have power over a single set of blueprints.

“Hany has amazing decorum and amazing sensitivity to the other individuals in the room,” says Mike Brown, development lead at Apple, which selected Hassan to help transform the Carnegie Library into the DC flagship store that opened last spring. Brown says the project was permitted and built unusually quickly, thanks largely to Hassan’s navigation of the agencies involved.

As skilled as Hassan may be at keeping the peace, his résumé includes the most controversial address in the city: the Trump International Hotel. I ask Hassan if he regrets his involvement in the transformation of the Old Post Office into the Trump property, given the way the President demeans immigrants. “I was very much focused on the renovation,” he says. “I’ve always separated anything personal from anything that has to do with [my] profession.” What mattered to him was saving an important landmark that was falling apart.

Still, Hassan acknowledges that the response to the building—which took him five years to restore—since Donald Trump was inaugurated has been difficult. “We worked very hard to get it to what it is. By everybody’s measure, this was an incredible accomplishment,” he says. “But after, there were a lot of protests and people did graffiti on it, and that just hurt me to no end.”

The recent news, though, that the Trump Organization may sell its lease there seems to buoy him. “It could be changed maybe into a corporate office building or a law firm, or maybe another hotel by another name,” he says. “But what I feel good about is that I gave this building a new life and protected it.”

Besides, he has plenty of other projects to focus on. His revamp of the historic Franklin School at 13th and K streets, Northwest, into the Planet Word Museum is approaching its May opening date. He shows off a model of the Randall School in Southwest DC, a long-abandoned space he has redesigned as a contemporary-art museum. He also devised the new—and very modern—12-story apartment building rising just behind it.

The Randall project’s pairing of old and new structures encapsulates his views about the appropriate role of historic preservation. “I think we all should have appreciation of the historic resources that we have, because they simply cannot be replaced,” he says. “But they cannot be stagnant. They cannot be a source of impediments for growth.”

This article appears in the February 2020 issue of Washingtonian.