The portion of District residents who spend more than half their incomes on rent jumped significantly between 2002 and 2013, while earnings barely inched up at all, according to a new study published Thursday by the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. The trends have left DC with a rental market in which many residents who earn moderate income struggle to find housing that eats up less than 50 percent of their wages.

“There is virtually no inexpensive housing left in DC’s private market,” says Wes Rivers, a DCFPI analyst who compiled the report. “Across the board, rents went up, and they went up faster than incomes.”

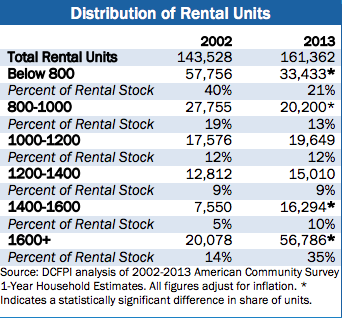

In 2002, about 40 percent of the District’s rental units went for less than $800 per month. By 2013, that figure, adjusted for inflation, was down to about 21 percent. Rivers estimates the 33,433 apartments he counted that rent for less than $800 today are all subsidized by either the city or federal governments.

The absence of low-cost housing has long been an issue for DC’s lowest earners, but the study finds that households taking home between 30 and 50 percent are feeling the pinch, too. Rivers reports that 31 percent of households in that bracket, which earn $32,000 to $54,000 annually, sent more than 50 percent of their paychecks to their landlords in 2013, up from 8 percent in 2002. And for households that earn up to 80 percent of the area median income ($107,300 for a family of four), the rate paying more than half on rent has jumped from 1 percent to 10 percent.

“Either pay half your income on rent, or pay for other necessities like food and transportation,” Rivers says. “Increasingly, we’re seeing middle-income renters do the same.”

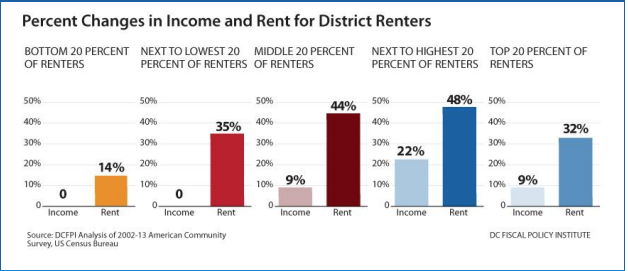

Incomes for the bottom 40 percent of renters did not change over the analyzed period when adjusted for inflation, while their rental costs increased as much as 35 percent. The middle quintile only saw their average earnings rise 9 percent from $41,990 to $45,970, while rents in that bracket rose 44 percent. Rents for households making up to 80 percent of the median income nearly jumped by 48 percent, while the top quintile of renters saw their housing go up by 32 percent.

In total, Rivers says one-quarter of DC renters are contributing more than half their pay toward housing costs. For households in the bottom 30 percent, severe rent burdens have long been the norm. But sluggish wage growth and a construction boom for luxury housing units have spread firmly into the middle.

Of the 161,362 apartments DCFPI counted in 2013, those with monthly rents and utilities above $1,600 account for 35 percent of the entire stock. Units below $1,200 per month make up 46 percent of the market.

The demands of a changing population, led largely by higher-earning residents who have arrived over the past decade, are rewriting the rental market, but at the cost of displacing low- and middle-income households, the report reads. Unaffordably high housing costs, DCFPI reports, forces families to move frequently, which in turn impacts adults’ employment and children’s educational opportunities. And don’t expect the market to make itself more equitable.

“As long as we have a healthy demand of new entrants into the city, we won’t really know until we know that supply is correct,” Rivers says. “There is a strong demand for higher-end units. At either end, you do see that there has been this shift. It does show a trend that we are having more units at the top end and we’re losing units at the bottom.”

The policy group says Mayor Muriel Bowser and the DC Council have made a few motions toward shoring up the District’s supply of affordable rental housing, but it also lays out a few heady prescriptions. DCFPI is wary that legislation passed in 2014 aiming to pump $100 million into the city’s Housing Production Trust Fund, which constructs and preserves housing for low- and moderate-income rsidents, will not be fully funded. (It gets its funding from a 15 percent cut of taxes collected from property sales, which has been a volatile source since the 2007-2009 economic collapse.)

DCFPI’s bigger order is a wholesale expansion of another housing assistance fund—the Local Rent Supplement Program, which serves very low-income families by paying their rents after a contribution of 30 percent of their income. Currently, the program serves 3,240 households. But with 25 percent of renters citywide spending more than half their salaries on rent, the DCFPI sees as many as 41,000 households on the brink.