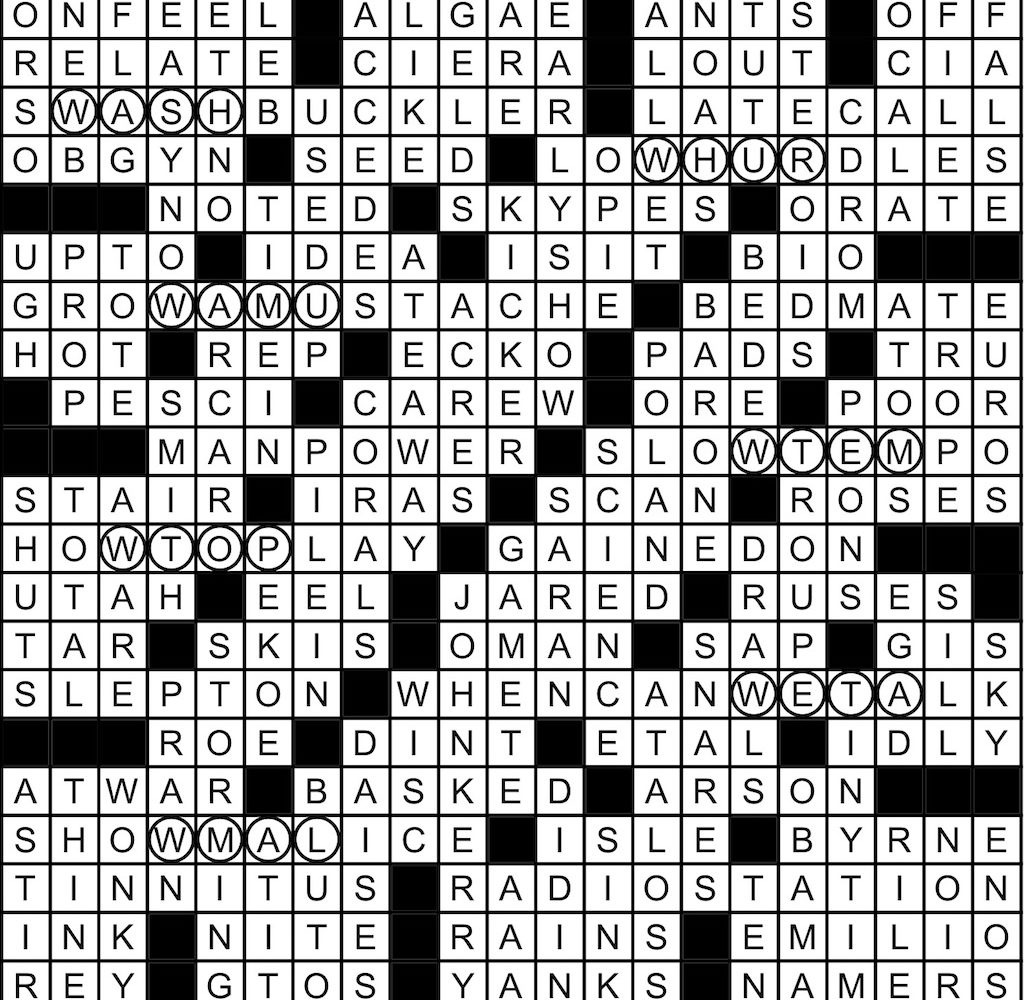

Fikile Mvinjelwa as Amonasro and soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams as Aida in Virginia Opera’s production of Verdi’s “Aida.” Photograph by David Polston, courtesy of Virginia Opera

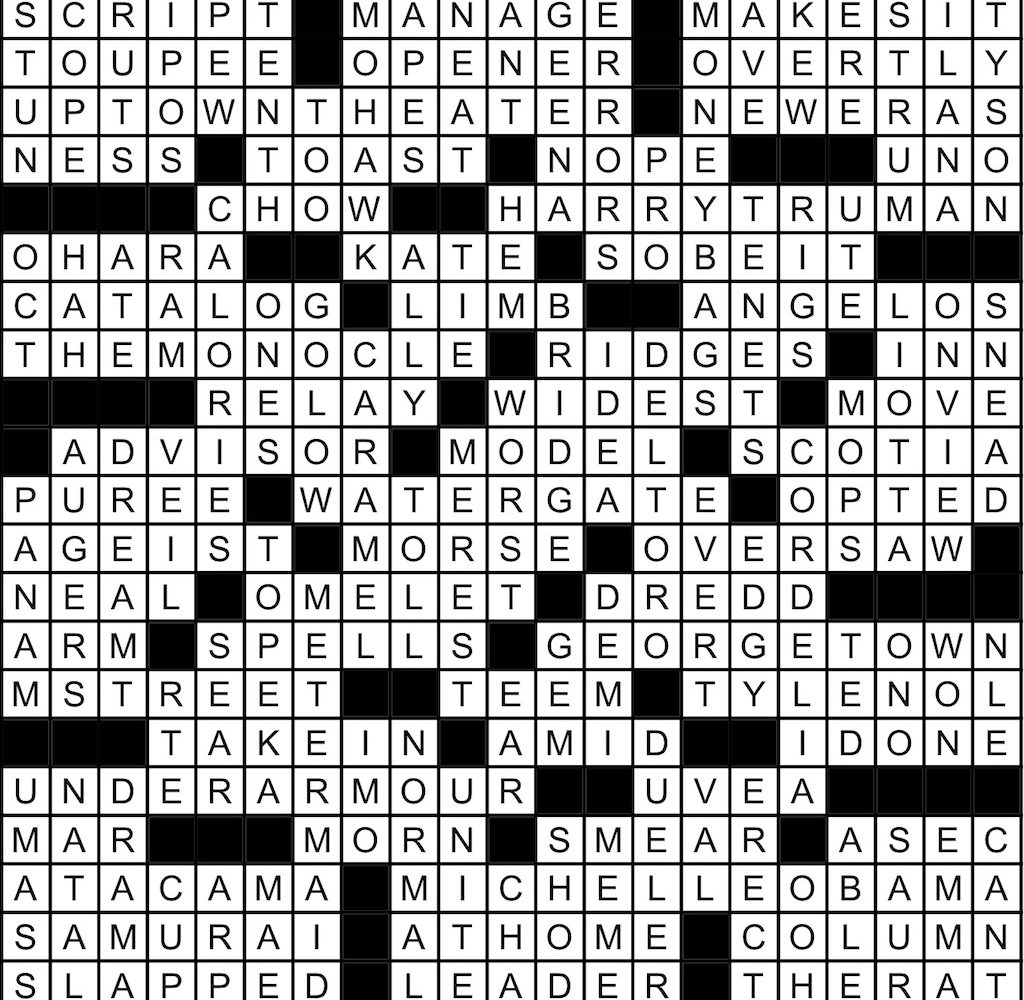

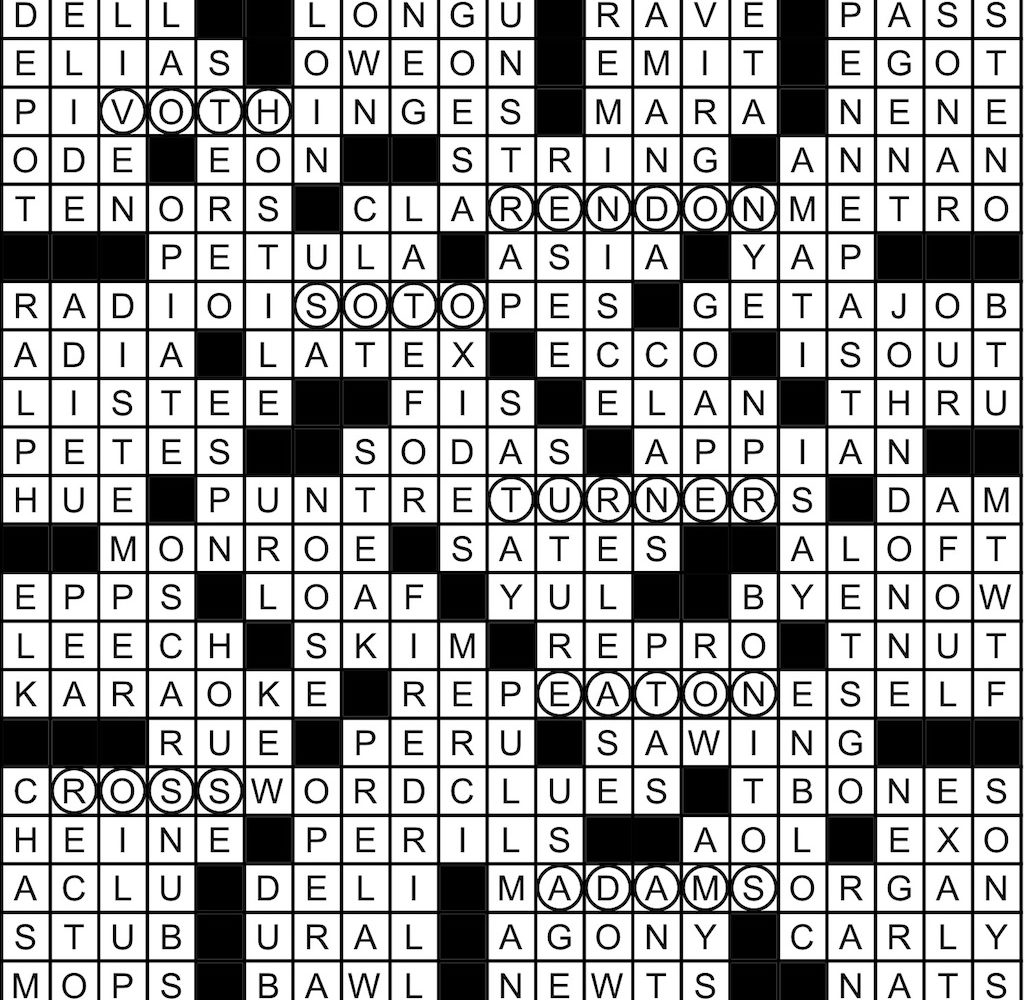

Aida has some of the most recognizable strains of music composed by Giuseppe Verdi, and yet it remains one of the least staged of his most popular operas (not heard from the Washington National Opera, for example, in almost a decade). Aida is a grand opera, packed with big choral scenes, ballet, and other spectacle—an Egyptian story made for the Khedivial Opera House in Cairo, with costumes and scenic ideas contributed by an Egyptologist. It is the sort of work that small, regional companies—like the Virginia Opera, which brought its new production of the work to the GMU Center for the Arts on Friday night—generally do well to avoid. The Virginia Opera, in fact, has just survived a schism in leadership, with board members, staff, and donors swarming from the hive to follow ousted music director Peter Mark—but nonetheless, it chose Aida to open its new season. It was a gutsy choice, and one that paid off; the slightly camp yet savvy production is a success, minimalist in set design but meaningfully directed in all its scenic details, and with a solid cast. Combined with a season of three other equally palatable operas, it is a good indication that the Virginia Opera is headed for a bright future.

On the heels of a fine performance as Tosca with the Virginia Opera in 2009, and as Adriana Lecouvreur with the Washington Concert Opera last year, soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams took on the title role. She sounded overall to be in good form, with a few scratches and strains that possibly indicated minor vocal fatigue. Williams’s voice rang out over the big choral numbers, but it was the softer moments where she shone brightest, kneeling to sing the Act I “Numi, pietà,” for example, in a serene pianissimo. In “Patria mia,” set against a plaintive oboe solo, and in the final scene with Radamès, she was equal parts musically expressive and dramatically affecting. Mezzo-soprano Jeniece Golbourne was every bit a match for Williams as Amneris, the Egyptian princess who holds Aida, the Ethiopian princess, as her slave. Golbourne has a photon-strength voice, with a viscous thickness in the chest and occasionally a little shrillness at its apex, giving her Act I duet with Williams the sound of a jealous, competitive edge.

As Radamès, the love object of both princesses, Argentinian tenor Gustavo López Manzitti (who has been with Virginia Opera before) hit all the high notes, some of them with force. His tone, leathery and shouted, was as stiff and hollow as his stage presence. Baritone Fikile Mvinjelwa, another Virginia Opera regular, howled a bit as Amonasro, Aida’s father, his overacting a match for his overblown sound. The supporting players—Ashraf Sewailam (Ramphis), Nathan Stark (the King of Egypt), and Kaileen Miller (High Priestess)—did fine work. The Virginia Symphony Orchestra played a near-complete version of the score (only some of the offstage parts were not included), and conductor John Demain held everything together ably and with sensitivity. A reduced number of string players made some of the passages, the violin ones in particular, a little weak and discolored here and there.

Erhard Rom’s set was a geometric arrangement of beams and what looked like louvered blinds, set in triangular shapes that suggested Egyptian pyramids. A bright solar disc descended, was eclipsed at times, and even carried a projected image of the life-giving god Ptah. Egypt was most strongly suggested in the costumes (a bit on the Cecil B. DeMille side of things, designed by Martha Hally) and makeup (by James McGough). Director Lillian Groag carefully organized the movement of the chorus, strong and unified (led by Adam Turner), and soloists, who all moved with purpose. The triumphal scenes did not have the grand spectacle of some stagings, but the grandeur of movement was cleverly suggested by eight beautiful dancers from the Richmond Ballet (choreography by Malcolm Burn), costumed as Egyptian gods, as slaves, and, in one memorable case, as a golden-winged goddess, who was lifted around the stage in flight, perhaps a depiction of Isis. It may not have been grand opera as a larger house would do it, but it was a performance of many pleasures, for both eyes and ears, in a small auditorium where one feels very close to the musicians. The tickets at Virginia Opera are priced at about one-third of the cost of those of the Washington National Opera. You can do the math.

Virginia Opera returns to Fairfax on December 2 and 4, with a production of Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel.