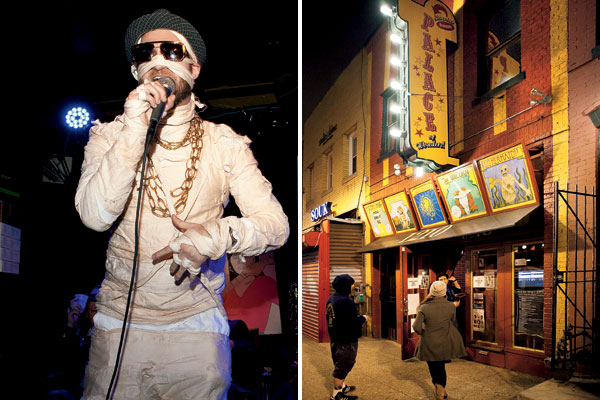

Rock & Roll Hotel, 1353 H St., NEA music hall with a lively dance scene and flying guitars on the ceiling (left). Red Palace1210 H St., NE Known for its burlesque and vaudeville shows; also has a museum of oddities (right). Photographs by David Phillipich.

He refuses credit for the revivals as quickly as he rejects blame for the demise of older, minority-owned businesses. Virtually all of the 27 businesses that have folded on H Street since 2003 were owned by blacks or Asians, according to Anwar Saleem, executive director of the nonprofit organization H Street Main Street. Many lacked the capital to survive the disruptions caused by street improvements and couldn’t keep up with rising property taxes or rents. Of the 174 new businesses that have opened, Saleem says, just a fifth are minority-owned.

When a community leader called a meeting in 2005 to discuss the wisdom of opening eight bars at once on H Street, Englert chafed at the implication that the neighborhood would be worse off.

Why shouldn’t residents, old and new, have nice places to eat and drink, he asked in a post to a neighborhood listserv. “Why are my 6 and 10 year old afraid to walk around H St. on a Saturday morning?” he wrote. “Answer: Perhaps it’s the two dozen or so homeless, urinating, yelling, screaming and guzzling malt liquor crazies populating the street corners that no one had the bravery to move along. . . . I have a plan to clean up H St, to recruit not just restaurants, but bakers, chocolate shops, museums, flower shops and more to the strip. What have others been doing except for joining alphabet groups and simply talking, not doing?”

Members of the local Advisory Neighborhood Commission told me that despite some initial hesitation, they gave their blessing to his liquor-license applications. His record elsewhere in the city and his responsiveness to concerns about noise, litter, and safety made an impression.

“Why gentrification is sort of not real,” Englert says, “is that usually whatever is lost is found somewhere else, or what’s lost is lost because it would have went away anyway. If there was some mom-and-pop place that was a great soul-food place or a great pupuseria, if the kids didn’t want to sell the soul food anymore or the grandkids didn’t want to sell pupusas anymore, what kind of tragedy is that?”

All the same, some black business owners, struggling to stay afloat, have found his dismissiveness tone-deaf. A few told me they chafed at the notion of Englert as “the great savior.”

“The richness of H Street doesn’t start today in 2011. It goes way back.”

“The richness of H Street doesn’t start today in 2011,” Bachir Diop, a Senegalese immigrant who owns a building a block from Englert’s bars, told me when we met last year. He was alluding to the street’s midcentury history as a thriving commercial hub patronized by African-Americans. “It goes way back.”

On a rainy Friday, I joined Englert at the East Potomac Tennis Center at DC’s Hains Point, where he takes lessons every weekday morning. When I entered the five-court tennis bubble at 8:45, he was in the midst of a doubles match. Englert wore a baseball cap and a T-shirt that said stewed, screwed and tattooed. The other players wore sportswear in muted solids.

Englert struggled at times to move his heft across the court. But he had a powerful forehand and was aggressive at the net. As I settled in on the sideline, he served an ace against Mary Granger, a white-haired professor of information systems at George Washington University.

“Take out an old lady!” he said. “See that?” He glanced over at me and let out his hallmark cackle, a boyish heh-hee-ha-ha-hee-hee.

After the game, I asked Granger, who has played with Englert for several years, about his style on the court.

“He’s really improved,” she said. “Early on, it was ‘Let’s hit the ball as hard as I can,’ which is how I think he is in life. Now he’s . . . . ” She paused, searching for the words.

“Got more finesse?” I offered.

Englert’s doubles partner, Joe Jozefczyk, a tennis coach at the Potomac School in McLean, snorted. “You will never see ‘Englert’ and ‘finesse’ in the same sentence, let alone the same paragraph,” he said. “Even though everyone agrees he’s a jackass, we still let him play with us.”

The bars Englert opened on U Street in the 1990s didn’t last long enough to see the run-up in property values there over the last decade. He spread himself so thin after his early successes that all his bars there–and a few elsewhere–failed or had to be sold. “We thought we were invincible,” he says. “It was a disaster.”

He considered getting out of the business, but he was a new father and worried about finding other work. Then out of more bad news came a stroke of luck. The landlord of the downtown building that housed the Insect Club wanted to end Englert’s lease. AARP needed the space. As compensation, the landlord offered him a lease on a Korean restaurant on Capitol Hill whose owner had been evicted.

Englert called the place Capitol Lounge and festooned the walls with political memorabilia. The bar was three blocks from the Capitol, closer than the standby Hawk ‘n’ Dove. Young Hill staffers packed in nearly every weekday night–a feat in an industry in which Friday and Saturday nights often subsidize the rest of the week’s losses. The bar became his highest-grossing. Within five years, he had made enough money to buy the building and open another bar–Politiki, with a Polynesian theme–down the street. Awash with cash, he flipped houses in transitional Northeast DC during the sweetest stretch of Washington’s real-estate boom.

But as the housing market topped out, Englert grew fidgety. In 2004, he got a call from Pranee Kensler, who had once owned a diner where Capitol Lounge staff ate after work. She wanted a new place and had heard that buildings on H Street were going for a song. Like U Street, H Street had never fully recovered from the 1968 riots. Did Englert want to give the place a once-over?

Kensler decided against buying. Like many others who had eyed the street then, her late husband thought the neighborhood wasn’t right. But Englert was smitten. “I was compelled by the fact that it was empty, nearly deserted,” he says.

How was that a selling point? “Separation,” he says–the potential for the sort of orders-of-magnitude growth impossible in built-up areas such as Georgetown and Dupont Circle. “A $150,000 building less than two miles from the Capitol?” he says. “Even if you just held and paid the bank for ten years, how could you not double your money?”

The city had set the stage for a comeback a couple of years earlier, promising tens of millions of dollars in street improvements along with tracks for a trolley line. But before the jackhammers arrived, Englert took a risky, early bet, snapping up eight buildings in a few months. When the press caught wind, property owners, sensing a shift in the market, began raising prices.

In fits and starts, young professionals ventured to a part of town long absent from tourist maps. New restaurants and cafes clustered around Englert’s places like Antarctic penguins huddling for warmth. Families with young children moved into the surrounding neighborhood, as did developers, who have announced plans for hundreds of luxury rental units and condos. In five years, commercial property values tripled.

The Flats at Atlas, a high-end apartment building opening this spring, advertises itself as “157 steps to the nearest bar” in “one of DC’s most of-the-moment entertainment, dining, and nightlife districts.” A decade and a half earlier, the strip was best known as the place where a 28-year-old DC police officer was killed in an unprovoked shooting.

But H Street is still at a pivot point. The construction mess churned up by the streetscape makeover–a five-year ordeal that ended in 2011–hurt many businesses. There’s no sign yet of the trolley. And daytime businesses have been slow to arrive. The street isn’t yet a safe enough investment for many national chains–which is fine by many people–but the owners of commercial buildings are asking rents beyond reach of the small entrepreneurs willing to move in now.

Englert would have loved to have 20 buildings on H Street, he told me one night, sipping a Baileys Irish Cream on the rocks at the Willard Hotel’s Round Robin bar. “We just ran out of money and people to run the places.”